Memorie.al / The poet Frederik Rreshpja, self-proclaimed as “the sorrow of the world,” departed from this life, but left the world awakened. He is identified as a poet of solitude, though he did not pursue solitude – rather, solitude pursued him. In his youth, he was not a solitary, hermetic poet, confined to some creative “ivory tower,” nor to any Dukagjini confinement tower; on the contrary, he was a traveler in love with his country. Yet, suddenly, a metamorphosis occurred – the poet was not accepted as he was a free and courageous voice, whom legends bring “with bloodied hair.” Thus, he was politically marginalized and pushed away from the world of letters and art.

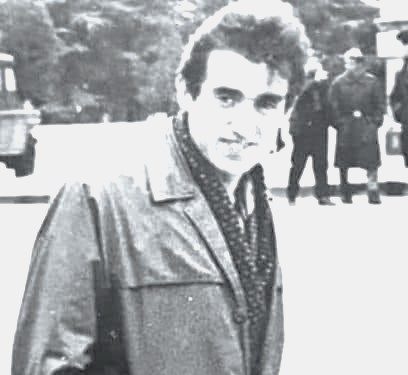

We had heard his voice since our childhood, when he published poems in “Dita,” “Nëntori,” or in the pages of the magazine “Ylli,” alongside a series of Shkodran authors of that time. As soon as he was “crowned” as a poet with his first book “Albanian Rhapsody” (1967), prepared for publication by Adriatik Kallulli, we were drawn to new books. At 15, we had read this author’s novel “The Distant Voice of the Shepherd’s Hut” (1972) – we are not aware if he wrote prose later, perhaps because prose required time, and by then, his time would soon be claimed by prison.

We then sought out Frederik as an author even in Shkodër, where we had gone for university studies, but he had shared the fate of Zef Zorba, whose name we did not even know back then. The city of Rozafa had been swept by the wave, and only under old chests could one find forbidden literature. There, “walled up” were living coryphaei of knowledge like Donat Kurti, entirely secluded from public life.

The poetry of the second half of the 20th century in Shkodër, and the northern region in general, was nurtured by modern poets such as Martin Camaj, Azem Shkreli, Ali Podrimja, Frederik Rreshpja, Ndoc Gjetja, etc., somewhere in the poet’s political exile, somewhere censored, unpublished, etc. In this context, Rreshpja was a cultivated poet who read in libraries, studied in lecture halls, wrote and published books unhindered within a short span of six years, publishing six books (poetry, novel, drama) – quickly becoming known in the literary elite of Tirana, as that had already become the country’s cultural center.

It is precisely here that his halt occurred, with the IV Plenum of the Central Committee (1973) which shattered literature and the arts. After this turning point, for Frederik there were only shackles and deprivation. He had already become a Kasëm Trebeshinë, Kin Dush, Pano Taç, Visar Zhiti, etc. The regime and the poet never “met,” because, as our literature teacher and publisher of “Camaj-Pipa,” Hasan Lekaj, told us, whenever a major political event was expected in Shkodër – a Party Congress, etc. – the police would go first with handcuffs and take Frederik, fearing that with his presence in public, he might spark something undesirable. This was his “ritual” – arrested and sentenced six times.

We do not know if Frederik was sentenced for any atypical poem or several such, but we know that other contemporary poets were punished for a literary figure, metaphor, metonymy, or figurative parallelism, such as: “I am the one I have not been,” “I am the sea extinguished,” etc. In other words, for a word. He says he followed “the curse of art”; otherwise, what for any poet in the free world would be fortune, for him turned into misfortune.

Rreshpja is not read today because he was persecuted yesterday, but because he is a poet of race. They extinguished his awakened world, and then his metaphor would no longer be awakening, but rain: “From now on, the rains will be my tears. May no one share this fate?” (“Testament.”) His poetic testament consists of the books “Albanian Rhapsody,” “In This City,” “The Hour Came to Die Again,” “Solitude,” “Seeking Ithaca,” etc.

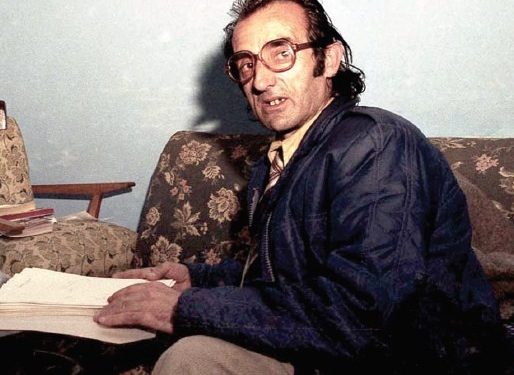

The thirty-year-old Frederik was a man of handsome appearance, without the scars of life on his face, with a poetry where one could feel the natural exhilaration of any poet who wishes to add his song to the winds of the country, to paraphrase one of his lines. Continuing the literary tradition of the 1930s, the first books of young authors, even in the 1950s-60s, if they did not mark peaks like Migjeni or Poradeci, constituted events not only in their creative lives, such as: “Young People, Ancient Land” (Bilal Xhaferi), “Albanian Rhapsody” (Frederik Rreshpja), “Morning of Sirens” (Xhevahir Spahiu), “My Voice” (Ndoc Papleka), “The March Within Us” (Natasha Lako), etc.

These books were as much introductory as they were affirming. There is continuity in their creative work and an authorial style, regardless of life circumstances and later creative perspectives. The poet proves himself independent of the official literary method, and Frederik’s lyrics of “socialist realism” are as artistic as his others from the time of unfreedom, such as “A Small Poem for the North,” where the lofty peaks no longer boast the clocks and crafts of Fishta, the weaving girls of Koliqi, the sorrowful toiling women of Mjeda’s “Andrea of Life,” the urban creatures of Migjeni, etc. We are half a century later and Rreshpja has a different sensibility:

“There the wind has carved its throne in stone,

There the sky is made of rain,

There the soil is made of snow…!”

The poet experiences the sensation of light from another perspective, from a worksite, where he hears “the drills of motifs.” The moving workshop makes him envision the world as ever-awakened. The motif of light in modern Albanian poetry is first encountered in Migjeni as absence, then in later poets, Kadare and others, as arrival. The cradle of origin, which determines their identity, is equally sacred for poets.

That cradle for Rreshpja is Dukagjini, or “The Land of My Grandfathers,” as another poem of his from the mid-sixties is titled. Martin Camaj weaves poetry with the mysticism of stone, grass, snake, rain, etc., while his fellow poet from the same region, Frederik, describes the land of his ancestors with a different dynamism, without excluding its legendary dimension, since the highlands had not yet emerged from the wake of the white ones (i.e., snow):

“I have a few çiftelia strings

Stretched over my soul;

Often the legend comes and plays them

With bloodied hair.”

There is no poet not drawn to dawn, since dawn is always the birth of light, even when it is “a dawn that colors the cave’s backdrop with light,” and when “tonight every house is a small dawn.” Isolators were a revolution in technology, and this could not help but be reflected in the poetry of the time – not as its “industrialization,” but as a light. As scholars have noted, at the core of structuring the poems of this period, Rreshpja effectively uses the image as a surrealist element. (B. Maholli).

3.

The metaphor of the “awakened world” is the metaphor of Rreshpja’s poetics: “Every morning I wake up early, but I find the world already awake. Good morning, world that stays awake.” The world is also present in his love poetry: “With love we have driven the whole world mad” (“My Sunday was you”).

All poets have “work” with the world, its mending, even when to others they may seem like crazed “Don Quixotes.” Frederik could not make the world his own and for himself, but he left his poetry as a medallion shining ever brighter. The world is his metaphor, as lyrical as it is sublime.

“Ah, when I was young and beautiful, I thought / That all the world’s rains fell for me, / But now so many years have passed / I know there’s no meaning to the falling rain.” (“Ave, My Mother.”)

For every poet, being understood by others is the meaning of existence, while not being understood is a tragic barrier, just as in Kadare’s Laocoon:

“Boyhood disappears behind the gate of colors / and sadness covers me / under a moon that does not know how to smile, / in a world that does not understand me.” (“The Sky of Boyhood.”)

This lack of understanding brings him sorrow, and this state he entrusts only to love to express, for only love has understood him in life:

“The seasons sadden me. / You have known this, / and from the world you divide me with a road / measured in kilometers of solitude.” (“The Death of Lora.”)

It is a solitude that he feels, “sees,” “touches,” since in his imagination it has walls, which makes him say: “these are the walls of the world’s solitude.” His poem “Solitude” is also an explanation of what has changed with it, in it, and for him:

“Where did this solitude come from like this? / Before it wasn’t here / Now it raises walls / And upon them drips the tear of silence.”

The poet mentions all those things he no longer gets to see, which solitude has taken from him: “the trees that become spirits,” “the whitecaps that die on the horizon,” “the sorrowful jasmine…”, “the lake, the black silent wind of the fog,” “this city with its old cobblestones / eaten by the horseshoes of legends,” “the fortress raised over the eyes of a woman,” because “everywhere solitude has raised its walls.”

Much has been written about Rreshpja’s poetry, where few other poets have had so many of their poems considered anthology-worthy; one could almost call him an anthology poet. The poet of the freedom of prison and the prison of freedom. The poems written in his cell (including in Spaç) are dissident, direct accusations against the regime and its leader, equally scathing towards the servile, the brainless masses, as he calls them, who do not see the blood flowing beside the tribunal, the phantoms of the martyrs, etc. He remained all his life in search of his Ithaca, but as an anti-hero. Thus, he could have been a poet without books, but not without poetry…

Post Scriptum: When we began this essay dedicated to Frederik, we do not know why words came to us in the form of poetry, without intending to dedicate a poem to the poet. Perhaps it was an attraction of his very poetry, which drew us more toward verses than prose lines: If ever we are overcome by sadness, lest the world fall into a deep winter sleep and not awaken without an “Albanian rhapsody,” let us whisper to that “sky made of rain” to awaken from its “stony cradle,” Frederik…!

The poet of strange fantasy would start from a simple detail, like the new shoes placed on the dead, to make them walk just as Dante did with the multitudes. And on the day he died, perhaps those who followed his funeral did not dress him in new shoes – not for lack of means, but because for him, the shoes with which he had described hell while alive were enough! Memorie.al