By Agim Xh. Dëshnica

Part One

Memorie.al / At a time when the dictatorship was rolling down into the abyss, some minor critics with academic degrees attempted to go even further. In the book History of Albania, Volume II (1984), the alienation of history crossed every boundary, with distortions of facts such as these: “The representatives of the reformist current linked to the Sultan’s regime aimed to limit the national movement only to a few cultural and economic demands. The expression of the ideas and the program of this current was Konica’s magazine Albania!” But who were these “representatives”? In the magazine Albania, Konica gathered around himself talented poets and writers such as Luigj Gurakuqi, Gjergj Fishta, Çajupi, Fan S. Noli, Asdreni, and Filip Shiroka – known in history as patriots of the fatherland’s freedom and independence.

Meanwhile, in the book History of Albanian Literature, one finds these lines of untruths, slanders, and insults: “Faik Konica (1875-1942). Son of an old family of beys, primarily a publicist, he began his literary activity with the publication of the magazine Albania (Brussels 1897) and directed for some time the newspaper Dielli of the Albanian emigration in the USA, where he spent most of his life.

From its first year, Albania was put at the service of Austro-Hungarian policy toward Albania. An unscrupulous politician, Konica was unstable, brutal, and aggressive throughout his life, attacking many progressive patriots on one occasion or another, attempting to discredit Ismail Qemali’s first government, or striking at the Congress of Lushnja.

After the counter-revolution of 1924, he allied with the Zog regime, attempted to treacherously harm Noli with polemics and threats, or to disparage the work of Naim [Frashëri]. Often he presented such a dark view of the country that he fueled distrust in a progressive future and generally in the popular and progressive force, defending, on the other hand, from the very beginning, the thesis that only the aristocratic elite was capable of leading Albania. All of this, dressed in a cloak of Occidentalism!”

However, this smoke-screen could not cover the light of one of the stars of the Albanian cultural and literary world: Faik Konica. Even after 1990, in the books History of the Albanian People III and the Albanian Encyclopedic Dictionary, Konica’s life and work, reconstructed by those same hands, are presented partially: “Writer, literary critic, publicist, essayist, one of the most prominent personalities of Albanian culture and literature!”

WHAT DOES THE TRUTH SAY?

The birth of Faik Konica on March 15, 1875, into a noble Albanian family in Konica – an ancient Albanian settlement – undoubtedly influenced his patriotic, educational, and cultural education and journey. He received his early lessons in his birthplace, middle education at the Jesuit College in Shkodër and the French Imperial Lyceum of Galata in Istanbul, and completed them in France. Afterward, he pursued higher studies in philosophy in Dijon and Paris.

There, in several competitions, by virtue of his intellectual abilities, he was honored with first prizes. He then left Europe and traveled to America. In 1912, he graduated in literature from Harvard University. The true history of Faik Konica lists a series of values: great patriot, politician, leader of the patriotic movement, and diplomat.

Above all, he is known as an activist in service of the nation, with his masterpiece, the magazine Albania, in Brussels and London, and his continuous links with the great patriots of the National Renaissance through letters and assemblies. The most fitting response to the slanders regarding his supposed love for “Turkophile beys” is given by Konica himself with his well-known satirical poem, “Anadollaku në mësallë” (The Anatolian at the Table), and the philosophical sayings scattered throughout his newspapers, magazines, and books. As much as Konica was strict toward the “fez-wearers” who wasted time away from the independence movement, he just as wisely laid out the issue of independence, writing:

“Truly, Albanians for now have begun to have an unrestrained desire for our language; truly, even the coldest among them have begun to understand that it is necessary to breathe life into the nation; truly, books and periodicals are coming out, in which the nation took a taste and without which it cannot live from this day forward; truly, in a word, things changed in a few years, and he who is not blind cannot deny that today the hearts of many Albanians burn for the progress of the Fatherland. But, despite all these, we do not have the happiness to see a true and strong union!”

Hasan Kaleshi, one of the serious researchers of Konica’s work, writing about the academic noise regarding his stance toward Austria, says: “Even if this portrait (of Konica) appeared to us with some spots, or even entirely negative as the dogmatists of Albania and, unfortunately, under their influence, some in Kosovo want to present it, still no one would have the right to remove Konica from our national movement, from our history of culture and literature. Because by removing him, we do nothing but impoverish our already not-so-rich culture and, consequently, impoverish ourselves!”

Similarly, the well-known scholar Namik Resuli, defending Konica, explains that: “Austria always protected the Albanians; otherwise, the Slavs and Greeks would have dragged Albania away!” In one of the books by the publicist from Kosovo, Bejtullah Destani, 1912 writing by the famous French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who met Konica in 1903 in London, is published. Among other things, he writes: “One of the people I have met and remember with special honor, Faik Bey Konica, is one of the most unusual!”

Apollinaire informs us that during his studies in France, Konica was tormented by longing for his homeland, Albania. Having returned to Turkey, he had participated in a secret movement against the Sultan. He was sentenced to death in absentia twice. Furthermore, the French poet tells an anecdote about Konica and the magazine Albania in Brussels: “One day he drew the attention of a policeman. He asked him: ‘What country are you from?’ – ‘I am from Albania.’ – ‘Where do you live?’ – ‘On Albania Street.’ – ‘What is your job?’ – ‘I work for Albania.’ – ‘Are you trying to mock me?’ replied the policeman, and thus the Albanian patriot spent the night in one of the police stations!”

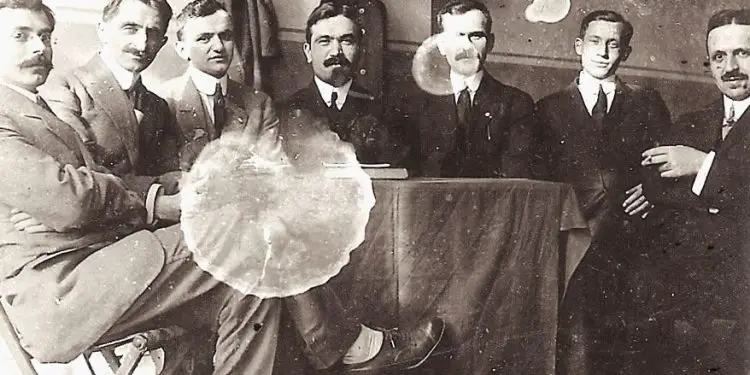

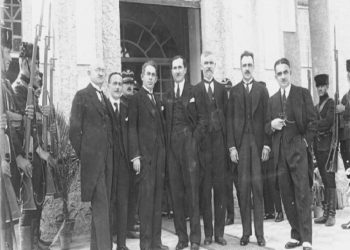

On April 14, 1912, Faik Konica participated in the founding of the Pan-Albanian Federation “Vatra” in Boston and was elected its general secretary. In 1913, Fan Noli and Faik Konica represented the “Vatra” Federation at the Conference of Ambassadors in London. In that same year, Konica was elected chairman of the Congress of Albanians gathered in Trieste for the protection of the territorial integrity of the fatherland. During the First World War and afterward, he performed diplomatic services for Albania in Austria, Switzerland, Italy, etc. In 1921, having returned to Boston, he was elected chairman of the “Vatra” Federation. Through the newspapers Dielli and Shqiptari i Amerikës, he supported democratic developments in Albania.

In the newspaper Dielli, January 22, 1922, Faik Konica wrote: “Fan Noli would perform the greatest service to Albania if he were able to instill a bit of the spirit of order, justice, and obedience amidst that drunken crowd, which endangers an innocent people, marked by the hand of fate for a near and shameful death!” Meanwhile, Noli, rising in defense of Konica in the Parliament of 1923, stated: “Faik is the chief-cultivator of our language, he is the discoverer of our forgotten flag, he is the chief-knight of national freedom and independence, and we all are but his disciples. Impartial history cannot deny this, nor can it deny that he has gifted the cause his entire youth and his entire mind for twenty-seven consecutive years without ceasing!”

Faik Konica, during the governments of the 1920s-40s, continued to serve Albania in the role of consul, then as minister plenipotentiary in Washington until the end of his life, on December 15, 1942. Letters from the beginning of the Second World War with King Zog, his ministers or secretaries in London, with Fan Noli in Boston, and the State Department in Washington, testify to his great concern for the fate of the occupied fatherland.

CULTURAL AND LITERARY ACTIVITY

Old professors and academics, lacking culture and poor in documents, since they have not dealt with Konica, write with conjecture that he created little or left some writings unfinished. On the contrary, all that vast activity in Albania, Europe, and America – the lectures, the endless writings in newspapers and magazines, hundreds of letters and documents being discovered in the archives and libraries of the cities where he lived and worked, such as Paris, Brussels, Boston, and Washington – testify otherwise. Thus, instead of professors, in the Albanian press, young writers and researchers periodically inform the general reader of findings of Konica’s writings, letters, and books.

Faik Konica is mentioned in the true history of our national culture as the creator of modern prose, a talented writer and poet with special sensitivities, a rare essayist, the founder of Albanian literary criticism, a publicist, translator, master of the Albanian language, and a scholar of other languages. In the intellectual circles of Paris, he was known as one of the most cultured Albanians, irrepressible in polemics when it came to defending the dignity of the Albanian nation, ready to respond in any language to those who insulted the fatherland, as only he knew how.

Faik of the Historic Albania

He spoke and wrote fluently in Albanian, Greek, Italian, French, German, English, and Turkish. Namik Resuli writes: “Faik’s prose is very pleasant, very polished and at the same time very simple and very fluid. It descends into the heart of the reader just like the nectar of the gods, which intoxicates and lifts the soul into another world, a world of endless beauties. The articles in Albania and Dielli, the columns of Dr. Gjëlpëra, and translations like those of the Arabian tales, constitute in themselves more than a complete and finished work. They will remain for Albanians as some of the most beautiful and graceful pages of prose, as a living model of Albanian, not only from an aesthetic point of view but also from the point of view of the language’s refinement.”

Konica’s literary and cultural activity in service of the fatherland traversed many paths in Europe and America. In 1895 in Paris, he brought to light the book Albania and the Turks. In Brussels and later in London, he published the magazine Albania and Albania e Vogël. In 1909, invited by Albanian patriots in America, he settled in the USA. In Boston, he directed the newspaper Dielli, and alongside it, the periodicals Trumbeta e Krujës, Ushtimi i Krujës, Bota e Re, etc. These political-cultural and literary newspapers and magazines of our Renaissance informed anyone of the rich history and culture of the Albanian people and the program of the national movement.

Some of these creations include: Dr. Gjilpëra Discovers the Roots of the Mamurras Drama, Albania: The Rock Garden of Southeastern Europe, A Zulu Embassy in Paris, Four Tales from Zululand, Albania as it Appeared to Me, and the translation Under the Shadow of the Palms. Unlike all the creations of socialist realism, Konica, with masterful narratives without insulting anyone by name, equips every reader with comprehensive knowledge and teaches how Albanian should be spoken and written. He writes with honor for good national traditions, education and morality, simplicity in dress and behavior, for true history, politics, philosophy, and the performance of duties in accordance with the laws in force.

Without embellishing anything, he criticizes the flaws of society without excess, with the clear goal of a patriot for further progress in our country. With advice such as “beware of yourself and of others,” he in a way addresses his compatriots as a parent and brother. Many of Konica’s creations have the hues of a poetic prose. Such are longing for the Fatherland, Some Memories of Father Gjeçovi, By the Lake, On the Lake, The Snow, The Life of Scanderbeg, Abdyl Frashëri, Naim Frashëri. From reading them, the sensitive poet of love for the fatherland and the nation’s heroes, for man and nature, is revealed.

Alongside his patriotic and diplomatic activity, the writings published to date, the beautiful Albanian language with a tendency toward unification, and the noble way of speaking are an example for everyone, even today – whether for poets, writers, and literary critics, or for Albanian politicians and journalists. Faik Konica, with his perfect criticism, evaluated everyone without exception according to their merits – poets and writers like Naim, Fishta, Father Gjeçovi, Noli, Asdreni, Çajupi, and even on political issues, Ismail Qemali, Ahmet Zogu, etc. Meanwhile, he remained their loyal friend until the end. We also highlight cases where Konica included some of Naim’s poetry in his critiques – about which socialist-realist analysts still make noise in vain today, while remaining silent about his overall evaluation of Naim’s work!

They forget that Konica, as a tirelessly demanding critic accustomed to the poetry of the great modern poets in Paris and London, while valuing the gift of our national poet, the expressive abilities, and the grace of the Albanian language, desired a Naim of contemporary European levels. Against all this noise, Konica, in the writing Naim Frashëri, lists a series of qualities of our national poet, such as: “joyful-hearted, sharp-minded, seasoned in words, finely sensitive, a bright and rare star in the sky of Albania!”

Father Gjergj Fishta, an admirer of Naim, called Konica “the arbiter of the most elegant writings of Albanian,” while Fan S. Noli called him a “brilliant erudite and great patriot.” To the poet Apollinaire, he was a “walking encyclopedia.” Konica signed his writings with various pseudonyms: Faik be Konitza, Faik bej Konitza, Faik Bey Konitza, Fk.B.K., FBK, Fk Konitza, Fk K-ntza, Fk K, etc.

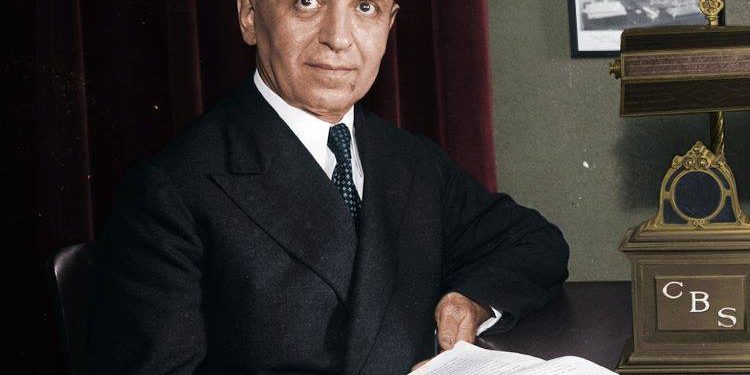

KONICA AS AMBASSADOR IN WASHINGTON

After the agreement and approval by King Zog as the diplomatic representative of Albania in Washington, Konica left Boston and reached the capital of the USA on July 11, 1926. After work, he would relax by listening to classical music – especially Wagner and Mozart. He adored the world-famous conductor Arturo Toscanini. At a reception at the Italian embassy in Washington, Konica had conversed with him for nearly an hour and remained fascinated by the depth and nobility of the great musician.

In the newspaper The Washington Post (April 1, 1934), it was written: “No one among the people of the diplomatic corps in Washington is better known or more liked than Faik Konica, Minister of Albania!” Throughout the time he was minister in Washington, Konica never let a summer pass without going for a vacation to Swampscott, a world-famous place for lobster fishing that attracted wealthy Americans and numerous vacationers from the world. In one of the buildings facing the ocean, Konica had befriended the owner, who invited him to stay for free for two extra weeks. The vastness of the ocean and the distance from the noise of Washington helped him calm his mind and his hypertension. Swampscott had one great advantage: the Albanian communities were nearby. He could take the bus or train to Boston.

KONICA AND NOLI

In 1937, Faik Konica had not seen Fan Noli for a long time. In truth, a chronology of their movements shows that Konica and Noli did not have many opportunities to meet in life. The history of direct relations between them began in 1909, when Konica first arrived in Boston from Europe. A few years later, in 1912, “Vatra” sent him and Noli to Europe. But due to work, the friends could not stay together. Noli returned to Boston in 1915 and, after four years, left again for Europe. Konica returned from Europe to Boston in 1921, while Noli was no longer there. They had crossed paths and communicated through letters during that time.

Until the end of 1924, there were only words of mutual admiration between the two. In the parliament of Tirana, Noli had been the great defender of Faik, who had plenty of enemies. In Boston, Konica repaid him with writings in Dielli, where Noli was presented in the colors of a hero representing “Vatra” there, where the most difficult battle for the fates of the new state was taking place – in Albania. Later, Zog’s return to power caused the relationship to break. Harsh exchanges began between Konica and Noli, which continued for nearly a decade. Although the polemic faded in 1934, pride did not allow the old friends to meet.

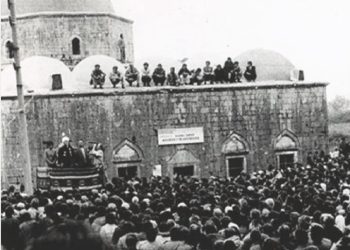

On November 28, 1937, the Albanian community of Boston celebrated Flag Day with a noted event. Konica also attended the mass that Noli gave that Sunday at St. George’s Church. After the mass, the Bishop presided over the “celebration of freedom” in the church hall, as it was called by Albanians, and the two had a warm conversation. The people around were ecstatic. The old generation of “Vatrans” watched history unfold before their eyes, while the younger ones, those who had not lived through the time when Konica and Noli fought for the new state, found it difficult to understand the symbolism of this meeting. Both had matured through struggle and had learned to look further than politics. From the interview that Konica gave a few weeks later to the editor-in-chief of Dielli, Nelo Drizari, it could be understood that a new friendship full of feelings of respect had begun between the two men.

Many are surprised by unbelievable phenomena, such as how in the years 1940-44 in Albania, students continued to be introduced to the life and work of Faik Konica through books such as Te Praku i Jetës, Rreze Drite, Shkrimtarë Shqiptarë, and Bota Shqiptare. Also, as often happened, while in 1955 in Pristina the complete works of Konica were being published, in Albania during the entire years of the dictatorship, every writing of his was prohibited. Under those conditions, when Konica’s writings were known neither by school pupils nor university students, it was noted that professors with leftist convictions exceeded every limit. In their efforts to devalue everything, they used foreign terms for aesthetic thought, far from truths and even contemptuous, such as: “reactionary,” “bourgeois-clerical,” “mystic-religious,” “formalist,” “unscrupulous,” “brutal,” “aggressive,” etc.

But at the time when the communist system collapsed, the professors – after having persistently distorted the life and work of Noli – rushed to publish Konica’s works for their own interests, since according to them they were no longer such, neither “reactionary” nor “formalist,” but “monumental”! And precisely due to incompetence and haste, one of them (Prof. N.) circulated with fanfare a worthless document, a “Will” supposedly written by Konica, with the plea for his body to rest in the fatherland. Nik Kreshpani, in the newspaper Dielli, October 20, 1965, sheds light on this issue raised by Noli in a meeting with some envoys from Tirana around 1945.

“They replied: ‘Very well; we can bury Konica in Albania, but first we must bring him before the people’s court.’ An inflamed Noli told them: ‘We hear day by day that you are judging your living opponents, but it never occurred to us that you were brave enough to bring the dead to trial too!'” Therefore, even the “letters” regarding this issue, supposedly sent “with considerations” to the dictator, and even surprisingly published in 1996 by these kinds of professors, are unbelievable and without any value at all. Memorie.al