From Shkëlqim Abazi

Part fifty-eight

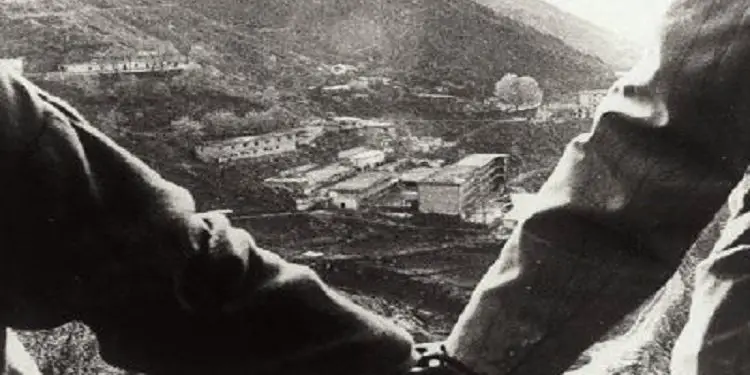

S P A Ç I

The Grave of the Living

Tirana, 2018

(My Memoirs and those of others)

Memorie.al / Now in old age, I feel obliged to confess my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds, and of others whom the regime silenced and buried in the nameless pits? In no case do I take upon myself to usurp the monopoly of truth or to claim laurels for an event where I was accidentally present, although I wholeheartedly tried to help my friends even slightly, who tactfully and kindly avoided me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you only have two months and a little left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet, from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months that followed, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard those three days, I would not want to take to the grave.

Continued from the previous issue

“O-ooo, Ja Abas Ali, they massacred the servants of Allah! In that gorge all hell broke loose those three days!”

“What happened, Mane?” – I inquired.

“A calamity, man! The knife went to the bone for those wretches! They were worn out and shriveled up from suffering, from not eating, from working three shifts in the mines, and also they would be tied to posts for the slightest transgression and locked in solitary cells. They were so fed up with life that they would approach the wire fences and beg us to shoot them! O-ooo, Ja Abas Ali, how much the poor man endures!”

“You didn’t shoot any of them?”

“I would shoot, but not to hit them. I would give the alarm until they were taken, bound in chains, and locked in the cell.”

“You never shot straight?” – the fellow villager egged him on.

“O-ooo, Ja Abas Ali! One night with rain and thunder, when I was a new soldier, a shadow broke through the darkness in the gorge of the stream, stopped for a moment, and then moved quickly further on. It was about ten meters away, but I couldn’t make out if it was an animal or a human. The shadow was crawling under the tangle of barbed wire, while the thunder deafened your ears.

I fired a burst. Better for him to die than for me to take his place! After the alarm, the ready group arrived, because we were not allowed to descend from the guard post, and they found a cat that had died in the proshkë (thicket/bushes). The first and last time I almost sinned, but thanks be to Abbas Ali Tomor, who saved me from sin!”

“What stands out in your memory from the days of the revolt?” – I returned to the topic.

“The moment when a young man, my age, addressed us:

‘Brother Soldiers, do not shoot in the name of God! We are not enemies; we have parents, sisters, brothers, like you and everyone else! Look, I am your age and should be a soldier like you, but they arrested me, without killing or harming anyone, and put me here. I have done three years, and I have seven more left. We are peasants like you, and we seek a better life, for ourselves and for others! Do not listen to the communist dënglave (gibberish/lies) who aim to turn us into enemies of one another, because they want the people to be slaves so that they can reign in peace! We invite you to unite, overthrow the usurpers, and save the people from the socialist scab! Let us live in peace, like the whole democratic world…’

“O-ooo, Ja Abas Ali, how beautifully that boy spoke! But we were paralyzed by fear and dazed by politics. But when he mentioned God, I got the shivers from emotion, and I shot into the air, I gave the alarm, hoping they would replace us. And indeed, it didn’t last; after five minutes, they brought police from Rrëshen, and we were moved across the stream, to the second echelon. It seemed they didn’t trust us, and from that moment, we followed the event from the opposite hill.”

“And after that?”

“Ja Abas Ali, we froze as if paralyzed by a spell! Especially when the slogans that all Albanians cheer today echoed in the Spaç gorge: ‘Either death or liberty!’ ‘We want Albania in Helsinki!’ ‘Down with communism!’ ‘Long live free Albania!’ ‘We are not enemies, we are martyrs!’ ‘We will not work in the mines, neither today or tomorrow!’ ‘You are murderers; you have stained your hands with our blood!’ ‘We will change places, because the circle is closing in on you!’ etc., etc.

A dilemma plagued everyone: ‘Without a doubt, these men are motivated by a strong impulse that challenges the state, even here, where a thread separates them from certain death! What audacity they have to react and demand rights, for themselves and for the people…?!’ At least, that’s how I, the wretch who came from the periphery, reasoned.

“And the others, did they think the same way?” – the fellow villager interrupted.

“I don’t know what to tell you about the others? Because we were afraid to open up to a comrade, but I am convinced that everyone was grinding within themselves: ‘these people see further than us ignorant peasants, and they know much, much more! How can a person risk their life without the conviction that they will leave something good behind?!’ I fully affirm that from that day on, the unrestrained propaganda of the leaders didn’t stick anymore. Despite continuing to serve in the same guard posts out of habit, something broke in our mentality, and we didn’t feel safe, as before…”

After I got the message I wanted, I interrupted him:

“Do you know Mersin Bardhyli?”

“Who, man? That stinking Enverist from Uznova, who cursed God and Abbas Ali?! When they took me there, I found him in his second year, but we couldn’t become friends because he was cruel and wanted to ‘take the blood to his knee…’ (be merciless/fight fiercely),” he concluded his confession!

The Slaughter Continued

They were shooting from many directions, especially from the guard posts beneath the command building, where they fired from top-to-bottom, and from the two side posts, one above the main gate and the other behind Met Karakashi’s clinic, from where the snipers fired. The relentless bursts reduced the flag fabric to a rag, but thank God, without casualties; the bullets hit the concrete walls and ricocheted. As the tracer rounds lit the sky in flames, beneath the red-and-yellow rivers of light, you could distinguish the contours of the hills and the skeletal tree trunks. From the surrounding guard posts and the trenches opposite, the batteries alternated with one another, turning into a cacophony of shots.

“You will be killed! Take your rooms and protected corners!”

“No one understood where this order came from, but they rushed as if commanded into the rooms, or descended the stairs to occupy some hiding place on the other floors.

“Why are you pacing like this, may your mind be shut? You’ll eat the final hit in the end, man!” – Xhelal Bey sneered at me from the second-floor landing.

“Where have you been, Xhelal Bey? You dried up our eyes!” – I replied, laughing. – “You have Xhelal at the forefront of the battle, but what are you looking for here, man?” – he tapped me on the head and added: – “Don’t grin at me, man, but gather the goats and cover yourself under the blanket, because you don’t have much time left!”

Darkness instigates strange psychic processes; perhaps it stimulates the ego, which turns even the cowards into heroes!

After a few minutes, the shots were forgotten, and the square was populated. The others occupied the palace balconies, while on the shower terrace, orators alternated, inviting their fellow sufferers to show tolerance, even towards the informers.

Near the mound of earth where the revolt began, my eye caught several people wrestling.

“Still spying around the corners, you stinking informer!” the ubiquitous Shuaip Ibrahimi threatened someone, while the others punched him in a group.

“I am pulling out the planks to feed the fire!” – the whining complaint of Hilmi Freskina was heard. I was glad about the lesson of “morality” they were giving to this immoral person.

“Down with communism!” burst out the spy who, after forty-eight hours, would leave no group without testifying against them. I abandoned the punitive expedition and approached the fire, which Fatmir Llagami, drenched in sweat, continued to feed. Although the night was warm, the flames devoured the sky, like an Olympic torch.

“The Committee has assigned two people to collect wood and me to keep it alive,” – Fatmiri told me.

“And Hilmi too?” – I interrupted on purpose.

“Hang the informer’s bag!” – Qemal Demiri threw the pickaxe with which he was tearing up the emulation stand, wiped his sweat, shook the droplets onto the flames, and continued: – “Beware of the informers, my friend, you don’t have much time left!”

Since he didn’t get an answer, he added: – “We need a signal for the paratroopers who might land from the air!”

Naturally, the hope turned out to be false, but in prison conditions, where every dream came to life, why not believe this fabrication too, which, after all, was worth raising morale!

At daybreak, the camp seemed to calm down, while outside the fences, the military vehicles continued the commotion, panting like breathless horses on the uphill slopes of Gurth Spaçit.

I lay down, but sleep had fled to the borders of oblivion. Dazed from a battle with a host (Mon) of hydras and baylozes (mythological giants), where all the spawn of hell attacked me at once: someone threw the German handcuffs on my hands, another the horse hobbles on my feet, and the third tightened my throat with a foaming, soapy rope, and I struggled to get free of them.

“Save me, O God!” – I was drenched in sweat.

A white devil, followed by two black ones, broke away from the crowd and took seats at a table with a red cloth, while Enver watched over them, and the shaggy-bearded likenesses of the Marxist theoreticians peered out from the backdrop of a gigantic poster.

“You are sentenced to hanging!” – Enver screamed.

“To hanging by the rope! To hanging by the rope!” thundered the Marxist theoreticians? “Hurrah! Long live people’s justice! Hurrah!” the frantic devils in the hall exploded.

As I struggled under the handcuffs, the chief devil with white hair, a white suit, a white shirt, and a beige tie, waved a white sheet of paper in his white hands.

“U-a-a, Faik Minarolli!” – the blinding whiteness of the court president blurred my eyes.

“The defendant attempted to overthrow the people’s power through a violent revolt!”

The whiteness blinded me; I shielded my face with my palm.

“Beware, son of the devil, because he is not always black,” my grandmother whispered to me. The sweetest voice in the world continued: “He changes form according to the occasion and circumstances. Sometimes he hides under the skin of playful girls, sometimes in that of mischievous boys, but often he transforms into a solemn official, a bureau secretary, a street prostitute, an ordinary thief, a policeman with chains and a whip, but most often into a white-shirted and collared judge!”

“You are sentenced to death!” – Faik, white-shirted and collared, scintillated dazzling whiteness. “Well done, hang him,” Enver ordered.

“By the rope! By the rope!” thundered the Marxist theoreticians.

“Hurrah! Long live people’s justice! Hurrah!” the frantic devils in the hall exploded. We were talking deliriously, because Fiqiri was forced to yell close to my ear: “Forget the heroics and see if you have any bread crust left!”

“What did you want, Fiqo?” – I replied drowsily.

“Bread! It seems they will sentence us to hunger and thirst!”

“Did they cut the water?” – Rama’s bucket was under the bed; the canteens and the bread bag were lined up on the shelf.

“They will cut off our heads, let alone the water!” – he stroked Tarti, who was stretched out under the bed. – “Come on, son, you fought enough all night!” – and he turned to me; – “Eh, man, did you find any crust?”

I handed him the crust my hand found. He split it into small pieces and was feeding the dog.

“Fill yourself up; if there is any left, give it to Tarti,” – I suggested.

“He is without a voice, my friend; we will figure things out somehow!”

The prisoner-animal bond was born with the genesis of humanity and strengthened over millennia. But communism turned it backwards, taming the animal through hunger, and brutalizing the prisoner with the same method. It thus produced the new man, the lejfeniste (a difficult term, potentially referring to a submissive/ corrupt animalistic state) animal, who hated his fellow man because they did not belong to the same caste, did not hold the same views, or have equal intellect.

Conversely, where it met resistance, it used violence in all forms, from psychological and physical lynchings to isolation in cells for months and years. What I have just written is confirmed by the slaughter of the class struggle.

Many unfortunate souls paid for the heresy with their lives; some were mentally and physically mutilated irreversibly, self-destructed, or ended up in psychiatric wards, and today wander desperately from hospital to hospital. The more responsible ones accommodated themselves to the conditions imposed upon them and strove to find ways and means to face loneliness with minimal damage.

Someone imposed maximum endurance, meaning they were split into a negative and positive role and dialogued with themselves. Another passed the time by creating imaginary figures, and still others invented allies: an insect, a bird, an animal, or a plant.

Thus was born the coexistence between the condemned and insects, birds, animals, plants, as a necessity that perfected itself over time. The protagonists of this symbiosis invested the missing love in each other, somewhat avoiding loneliness and oblivion.

In an earlier chapter, I touched upon this topic. I mentioned allies that could be animals, birds, or reptiles, ranging from the swallow of Burrel, the broken-winged “Bilku” of Shtyllas, the limping horse of Thumanë, the seagull of Skrofotinë, all the way to “Tarti” of Spaç, where I dwelt longer, due to the fact that he is engraved in the memories of politicians as the world’s only executed anti-communist dog. I believe the annals of history will record him as such.

But, besides Tarti, in Spaç we also had three noble friends and a flock of pigeons who, though not so famous, we cannot forget, because with them we killed time. The first was the old dog, “Baliku” or “Llesh bardhi,” the second was “Kuqua,” a decrepit horse whose ribs could be counted under its skin, and “Pisi-pisi,” or Tefa’s cat.

“Fur-white,” of Bajram

In fact, Llesh was the name of one of the fifteen or twenty free firemen who like all Mirdita people, we couldn’t learn his surname, but we distinguished him from the flock of Lleshs because of his features. He stood out for his completely gray hair and his beard hair, an inch long, so much so that you would say the cloth of the grinding mill had covered him, while the embers of his eyes shone brightly amidst the whitish mass, like a ball of snow.

One winter day, Lad Shena had to relieve himself. He split from the group and went to urinate behind a bush, above the gorge of the mine. From inside, a white-to-gray beast snarled at him, which startled him and made him turn back. After some dilemma, curiosity triumphed; he stared and was convinced that he had a dying and exhausted dog in front of him. He took a crust from his coat pocket and threw it; the miserable animal sunk its yellowed teeth into it and devoured it instantly.

The next day he returned deliberately to the bush and found it in the same position. He was finally convinced that it was either caught in a snare or wounded. The crust of bread fell a few meters away, the dog crawled, gasping, and swallowed it greedily. So, something else was tormenting it.

He called his compatriot, Bajram Dervishi himself, who, as soon as he saw the snarling teeth and eyes full of gunk, exclaimed:

“What is this scabby thing that resembles the flock dog in its head and stature, the bitch!” – Bamka mocked.

“It seems he doesn’t know dogs at all!” – Lad told him.

“Brother, I grew up with them and I know them well! This yellow-toothed blind thing has its skin falling off in pieces, as if it has the mange!” – When he offered the dog the crust, the dog snatched it instantly. – “U-ah, he is not as finished as he looks!” – Bamka drew back, surprised.

After four or five days, the animal recovered, abandoned the bush, and followed its new friends all the way to the entrance of the mine. After that, it didn’t wait to be visited in its lair, but wagged its tail, waited for them to throw the crust, sunk its worm-eaten teeth into it, and accompanied them again, all the way to the mouth of the tunnel.

Once it started eating, its body filled out, its fur shone, and it took on a flashing whiteness, just like a ball of snow. Now the gunk was cleaned, and its eyes shone brightly amidst its shaggy head, like those of Llesh the fireman, with whom it resembled a photographic copy of an identity kit.

Lad called him “Balik,” but he didn’t respond; perhaps he was too old to get used to the new name. When Bajram called him: “na-na, lesh bardh (Fur-white),” the dog wagged its tail and followed him.

From that day on, Bamka, for a laugh, called him “Llesh-bardhi” (Fur-white).

It wasn’t long before “Llesh-bardhi” made friends with everyone. He waited for us to throw the crust, rubbed against our knees, but as soon as he completed the “custom,” he solemnly departed to his own lair, from which he wouldn’t deign to emerge, even if you shouted for hours.

When we learned that the fireman’s surname was “Kryeziu” (Blackhead), a nickname that did not match his appearance or that of the dog, we continued to call the dog “Llesh-bardhi.”

But one day “Llesh-bardhi” abandoned us; it was never understood whether the soldiers killed him while attempting to escape outside the perimeter, or if he returned to his old craft: fighting with wild beasts in the mountains?!

“Kuqua,” the Decrepit Horse

The horse, abandoned by some cooperative, was used by the command for transporting food and bread, from the central bakery to the intermediate points along the perimeter, but they abandoned it due to a lack of a food base. “Kuqua” was old and weak, stumbling over its own feet; its bones could be counted on its back, just like a didactic skeleton!

Although it grazed dozens of hectares inside the mine perimeter, it never put on weight, because in the winter in Gurth-Spaç, you couldn’t find a blade of grass, due to the snow and frost. Thus, “Kuqua” remained the only animal that owned the territory of that whole area.

After the “betrayal” of “Llesh-bardhi,” Ladi became affectionate towards “Kuqua.” He would throw it a bread crust when he found one, gather grass for it in the boundaries when there was some, while in the winter cold, he would “steal” straw from the prisoners’ mats and give it to the decrepit horse. Thanks to the care, “Kuqua” recovered, its coat shone, and it started kicking its heels. Then, it would rush from the second zone to the connecting gate, three times in twenty-four hours, eat the provisions that were thrown to it, and return again, to graze with its own mouth.

Upon seeing Lad, it would leave grazing and trot towards him, sniff him, and play its head up and down as if communicating in a language only the two of them understood. Since it hadn’t worn a saddle for a long time, it lost the notion of weight, but in front of Lad, it would make itself a bridge until he jumped onto its back and they raced for pleasure, from the pumice-topped Calvary to the second zone, or vice versa.

But once it betrayed him, almost costing him his life! I don’t know if it was its brain or a horsefly bite, but it took a crazy bolt down the slope of the first zone and continued straight towards the main gate. Lad noticed the danger when he needed to take the curve of the footpath, about ten meters away from the guard post, but the horse didn’t stop running, and even when the soldier yelled: “Stop, or I’ll shoot!” it sped up. The rifle cracked, and Lad threw himself head over heels from the horse’s back, landing in the dust with a sprained ankle, but thank God, he escaped the bullet! Memorie.al

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)