From Dom Zef Simoni

Part ten

Memorie.al publishes an unknown study by Dom Zef Simoni, titled “The Persecution of the Catholic Church in Albania from 1944 to 1990,” in which the Catholic cleric, originally from the city of Shkodra, who suffered for years in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime and was consecrated Bishop by the head of the Holy See, Pope John Paul II, on April 25, 1993, after describing a brief history of the Catholic Clergy in Albania, dwells extensively on the persecution suffered by the Catholic Church under the communist regime, from 1944 to 1990. Dom Zef Simoni’s full study begins with the attempts by the communist government in Tirana immediately after the end of the War to detach the Catholic Church from the Vatican, first by preventing the Apostolic Delegate, Monsignor Leone G.B. Nigris, from returning to Albania after his visit to the Pope in the Vatican in 1945, and then with pressures and threats against Monsignor Frano Gjini, Gaspër Thaçi, and Vinçens Prenushti, who sharply rejected Enver Hoxha’s “offer” and were consequently executed by him, as well as the tragic fate of many other clerics who were arrested, tortured, and sentenced to imprisonment, such as: Dom Ndoc Nikaj, Dom Mikel Koliqi, Father Mark Harapi, Father Agustin Ashiku, Father Marjan Prela, Father1 Rrok Gurashi, Dom Jak Zekaj, Dom Nikollë Lasku, Dom Rrok Frisku, Dom Ndue Soku, Dom Vlash Muçaj, Dom Pal Gjini, Fra Zef Pllumi, Dom Zef Shtufi, Dom Prenkë Qefalija, Dom Nikoll Shelqeti, Dom Ndré Lufi, Dom Mark Bicaj, Dom Ndoc Sahatçija, Dom Ejëll Deda, Father Karlo Serreqi, Dom Tomë Laca, Dom Loro Nodaj, Dom Pashko Muzhani, etc.

My Writings

My thoughts and actions revolved around the Person of Christ. I planned for my life to have three goals. First, to focus on an internal spiritual progress, according to the Father’s doctrine, proclaimed by the Son, who is Jesus. Second, to be present for the faithful in spiritual needs, during such difficult times, speaking the word of God in my conversations with them and administering the Holy Sacraments. Third, to dedicate myself to writings, both for pleasure and for the needs of society. Oh, to dedicate oneself to writings! For a word you write, you carry responsibility. You draw out thoughts, ideas; you present earthly and heavenly problems, history, people, struggles, and contradictions. You say this. No, that. Writings require content and form.

I had started writing compositions since the higher grades of the lycée, which the literature teacher called beautiful. Even during my time in education, I wrote, but I couldn’t show them much to anyone, as they had content that was like a reaction against the times. I considered some of them beautiful, but when the churches were closed, I destroyed them. I had a firm conviction that my writings should have religious and social matter simultaneously, with a Catholic viewpoint. Life must not be separated from faith. There are not two lives on this earth. On the one hand, life as one category, and on the other, faith, as another category. Even if I were to write a description of the ox, or the donkey, I would connect it to the fact that they were found one night in a cave. If I were to describe the sun, I would definitely talk about the “Sun of Righteousness,” who is Jesus.

If I were to write about the star, I would describe the Star of the three Magi from the East, who go to adore Christ. To talk about wheat and wine, I would talk about the Eucharist. And given that faith is valued even more when obstacles, limitations, and chains are placed upon it, when freedom is lacking, its necessity is seen more clearly. And with my writings of this nature, I thought I was doing a great service to God, the people, the nation, and the faithful. One day, I was staying in the office room of the Archbishopric. It was February. Beautiful snow began to fall. The sky was full of clouds. Life was full of troubles. Our world was full of wars and angers. Ideas were full of mistakes. The room was warm with fire. I was alone. Suddenly, an idea and an inspiration came to me to write something about Christ, like a short biography.

I wrote a few pages. No more than six typewritten pages. It began like this: “God Himself brought salvation. And one night the Light came. The shepherds went to the Shepherd. The lambs went to the Lamb. And the three kings went to the Infant. They brought gifts: gold, frankincense, and myrrh. They recognized Him as King, as God, as Man. Later, everyone will know Him.” I showed it to a few clerics. They judged it to be beautiful. Father Meshkalla read it carefully and told me that such writings were needed in the present time. François Mauriac is a very great writer. “You, too,” he said, “seem to have a style like his.” I had not read anything by Mauriac, but later, I held this writer very dear to my heart and considered him a guide. My works were read by Monsignor Ernest Çoba, Dom Kolec Toni, Father Mark Harapi, and they were delighted with these pieces.

Professor Gaspër Ugashi, whom we children called “uncle” because he was my mother’s first cousin, gave me special appreciation for: ‘The Life of Our Lady’, ‘The Life of Saint Joseph’, and ‘The Life of Christ’. This esteemed professor of the city of Shkodra would be a great benefactor, along with his three married daughters, during our twelve years of prison, helping with love and kindness. May God reward them and all the others who helped us, even in the future, during the years of prison, such as: Simon Moni, my uncle’s son, Gjovalin Gjini, my mother’s cousin, Zef Toma, from Juban, Doctor Terezina Suma, my cousin, and Tade Shiroka. After the events that occurred with the closing of the churches, I found comfort when I wrote. Mostly shorter works.

I titled one work: “An Unbreakable Weapon,” which described the 15 signs of the Rosary, and pieces of a book titled: “The Seasons.” Exhausted and worn out by illness, I was preparing to go to Razëm for the first year. I often went to the Castle (Kalaja), up to the place where the Church of Our Lady had once been. Now it was a monument with the star of violence. Sometimes tears would escape me. I have cried very rarely. But the tears came from the depth of my soul. Many appeared to me, and I uttered the words: cursed history. Before reaching the place that was the Sanctuary, I would sit down to rest on a rock, from where I could see the mountains, the Alps, a part of the lake, and the place where the small church of Saint Mary Magdalene once was, a part of the city, and all this land was closed, a closed homeland, a closed history, and silent castles, with suffering inhabitants, without hearth or home.

It was the day of June 24th, the commemoration of the birth of John the Baptist. John is connected to Christ. They are contemporaries, with a difference. John, six months older than Jesus. But their homes were far from each other. They would meet at the age of thirty, by the historical Jordan River, on a day of testimony, when Jesus would be baptized by John. As I was returning from the site of the Church of Our Lady, to go home, an inspiration came to me to write something about the precursor of Christ. On the way, I formulated a few sentences, and immediately, as soon as I returned home, I put them on paper. I worked one day, two days, on this subject, and I liked the work. “What if I wrote something about Christ?” I thought. “What if I started His great life?” I decided. And this thought did not leave my mind during the summer season in Razëm.

In September of 1970, having a good improvement in health, I started this great work, to write a literary life of Christ. I had material. Also preparation from my theological studies. This work would have many ideas, many ideals. Among the main ones is sacrifice. Christ’s sacrifice is suffering that becomes ideal and recompense. The recompense was needed, because the Father, God, had been offended. No human could make the recompense. Not even all people together. A limited being, such as man, or all limited beings, such as men, could not compensate the Unlimited One. Only the Son of the Father, He who is also God, who is His contemplated object, in eternity, out of love, desired to assume human nature. Then, as a man, he made the sacrifice and suffered, and since in His own person, He has two natures; the human nature, as Divinity, He fulfilled the offended justice with unlimited power.

Thus, the Father was recompensed, and at the same time, the right to salvation for people was gained. Christ was the Recompenser. Christ was the Savior. These were the juridical reasons for His coming into the world. That this universal Person with two natures belongs to every nation, every land, and will bring triumph through love for the Father and love for humanity. At the moments of His birth? Certainly, yes. Then enough, O Jesus! What more did you need? But no, because Jesus wished to be an example for us, our leader, the attractor of minds and hearts. Christ, by suffering Himself, gave perspective to our sufferings as well. “Do not be discouraged,” He tells us, “when they curse you. They did the same to Me, the innocent one. Nor when they offend you, trample upon you, torment you, torture you, kill your body, because all these things happened to Me.” Christ died on the cross and rose again, to definitively bind us to love and recompense. Jesus remains for us: “The Way, the Truth, and the Life.”

To embark on this work, the arrangement of facts was needed. I had the Albanian translation of Weber’s work, translated from German by Father Benedikt Dema. I was reading Life of Christ by Giuseppe Ricciotti. The works on the Life of Christ by Didon and Papini came into my hands. At home, I kept the great treasure: Life of Christ by François Mauriac. I read them all with pleasure. Each had its own beauty, style, art, and power. They were world masterpieces: Ricciotti with a historical work on Christ’s existence, Didon with a gentle presentation, Papini furious. I particularly liked Mauriac, a writer with internal power, with elegance throughout the work. The four Evangelists were insurmountable in the simplicity of truth and style. No one can write like them. I began the work: I lived with Jesus.

Palestine, Bethlehem, Simon the Elder, Nazareth, the Jordan River, Capernaum, Cana of Galilee, the Synagogues, Jerusalem, the Temple of Solomon, the fishermen with their names, the Merchants’ Inn, the Creator’s whip, the mountains, the eight beatitudes, Mount Tabor, where the Transfiguration of Christ occurred, publicans and Pharisees, Simon the Pharisee and the repentant sinner woman, appeared before me. Also, the woman with the seven husbands, at Jacob’s Well, and the event of the adulterous woman. Jesus, the Good Shepherd, and the parable of the prodigal son. Jesus and the Apostles in the boat, when he commands the winds to cease. The words: “Behold, rise and walk, your sins are forgiven,” Lazarus, “Veni foras” (Come forth), Talitha Cumi. The multiplication of the loaves and fish, the Upper Room (Cenakulli), the denial of Saint Peter, and the betrayal of Judas, Christ’s prayer in Gethsemane, the seven words of Christ on the cross, the Virgin Mary at the Cross, and Magdalene even at the dawn of the day of the resurrection. The Ascension of Christ into heaven and the Coming of the Holy Spirit. The glorious Church of Christ.

I would write the events according to chronological order, but sometimes I would not work according to this order. At one moment, I would write the birth of Christ, and the next day, His Resurrection. I had my disposition of the day, of the moment, of the inspiration. I was writing this work with love, purity, and sincerity. I was sometimes furious, and sometimes I was calm, joyful, sorrowful, energetic, fast, slow, angry against evil and benevolent toward the sinner, and forgiving toward the enemy, abnormal in condition, very normal in doctrine, with the ideas and teachings that are supported by the word and work of Jesus, by the infallible power of the Church, by the scholars and geniuses of all times of Christianity, by the certain conclusions of Christian life with the saints and monuments.

I began to write this holy and original life of Christ, in our conditions, because we were pushing this Jesus away. We did not know Him, we did not love Him, and we did not allow His voice to be heard. Violence dominated, not kindness, war and not peace, disorder and not harmony, interests and not ideals, bullets and not the Cross, the Internationale and not Tu es Petrus (You are Peter), class warfare and not Pater Noster (Our Father). For nearly four years, day and night, and whenever I woke up at night, to write this work, I delved into all the squares, streets, corners, words, walking with Jesus, with the new world, with His era.

In the year 1974, I worked on the Virgin Mary, the Mother of Christ. With an inspiration, an experience, and an elevated spiritual state, I finished The Life of Our Lady and The Life of Saint Joseph in three months; I worked on the Holy Family, for which my mother also had a special devotion. I read these works to my parents, my brother Gjergji, and my sister. The writings were like a prayer for me. They were busy years, lots of work, with soul and joy amidst the events of the homeland, which was a tunnel, a catacomb, and nothing else, an encircled homeland, mountains and wires.

In Clandestinity

The Homeland in Clandestinity

Our homeland was everywhere of one kind with the socialist façade, and its general nature encompassed every specific detail. Everywhere I saw the slogans of the revolution, that cultural one, of the evil fury of the class struggle. Albania and Shkodra were under major attacks. Orders always came from Tirana, and Tirana historically received them, initially, from Belgrade and Moscow. Now from Beijing. But Shkodra also had its own issues. Personal commands. Personal passions, with the forms of communist and oriental style, deeply Turkish in their essence. When the bell towers and minarets were torn down, it seemed as though the city’s head was cut off. A city without a head. The city no longer had shade; it lacked the traditional pleasure, with the bells that had been like vertical bridges, to cross through them, from earth to heaven. The city and the homeland had their connections severed – the connections that make it strong with four forces: feet, hands, mind, and heart.

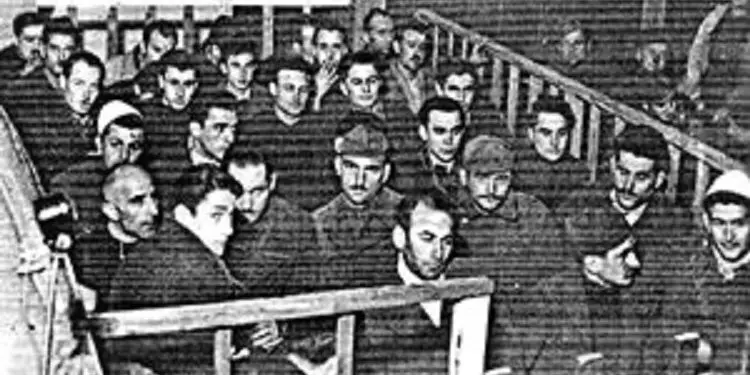

The first fury of closing religious institutions with swift orders passed, and now other orders and planned furies were arriving. Heavy trials against priests, against Dom Mark Hasi and Father Meshkalla, arrested in front of the Pedagogical Institute, in the presence of thousands of people. And then the trials in Shkodra, in the Church of the Stigmatine Nuns, against Dom Frano Ilia, Dom Zef Bici, Dom Mark Dushi, and Father Gegë Luma. Dom Zef Bici and Dom Mark Dushi were executed by firing squad. There was talk against the Church, the Papacy, against Christian civilization and Europe. Continuous, noisy meetings. For two or three good years, every person was beaten and every home was held in suspense. Houses looked as if they were torn from their foundations, and many people were thrown into disorder, and many who had fallen so low went to kiss the walls of the committees. Cry out, O God, against the evil in this earthly suffering.

The Franciscan Church of Gjuhadol was turned into a cinema hall. They took this church, and the bones of Dedë Gjo Luli, preserved with such reverence by the Franciscans, and they were destroying them along with the bones of the friars and of Father Gjergj Fishta, our national poet. The historic Cathedral was turned into a Sports Palace, where even half-ballerinas would dance, and cold Christians would applaud for basketball players and goal scorers. There was even more in this church, as the dictators would hold atheist speeches, violating the religious rights and feelings of the entire populace. In a women’s congress, the women led the leaders and incited them to commit dark deeds with their scornful words.

When the city trembled, the nation cracked, and terror entered every home. The press was right when it wrote that people should not think we had destroyed religion just because we closed the institutions. Religion has deep roots. Much work is needed to be done. A continuous struggle. In words, it was said that the people had closed the churches and religious institutions, but in deeds, it was shown that religious ceremonies were held everywhere. There were baptisms, prayers, and the keeping of holy statues and crosses. Christmas, Easter, and the two Bajrams were celebrated. It is well known that fear had seized the people, but the people had their own ways of preserving a certain belief.

In the years that followed the closing of the churches, at the liquor store, a non-private shop where Pjetër Bushati sold, in the center of the city of Shkodra, on the Night of Saint Nicholas, there were long lines on both sides of the shop. Wine and raki were sold. Wine and raki for Saint Nicholas. The state had not thought of this activity. Wine and raki were bought in bulk, even two weeks before the holiday, and roosters were crowing in many homes. Later, after a year or so, one could hear the chorus formed by the roosters, which had been bought to be slaughtered according to tradition, on the Night of Saint Nicholas.

In an apartment two days before the holiday, a rooster betrayed the secret. Although tied up, it freed itself and flew like an enemy airplane, on the vigil of the holiday, and the celestial saboteur fell from the fourth floor onto the ground, in the middle of the street, between the “Republika” Cinema building and the Officers’ House. Laughter and suffering. “Religious incident! A form of religious activity. It warrants a meeting. Whose rooster might this be? From which house did it fall?” Then, for the Feast of Saint Nicholas, people sent laknorë (a type of pie) and sweets to the baker to be baked. People sought to buy dried figs and walnuts. Christmas and Easter would be felt in every home, and the celebratory meals and visits for name days would now continue for two or three weeks, so as not to attract attention.

Dom Injac Gjoka

The city, villages, and highlands were under a heavy cloud and fear. The Monsignor was living in the “Arra e Madhe” neighborhood, in a critical house, as it was not under the keys of the Security (Sigurimi). People were coming and going, especially villagers, for religious services. The same happened in a room where the holy priest, Dom Injac Gjoka, was residing. His room became a church, from 7:00 AM until 7:00 PM. Dom Injac had been summoned several times to the offices of the Front and to large meetings, to stop providing services, and he had been warned of arrest. Dom Injac did not waver from his duty. I was becoming known to the people as a priest, through the Monsignor and Dom Injac, who connected me with many people for religious services. And my word as a priest spread. In this case, I had an easier time with clandestine service, even though I had many acquaintances. Dressed very simply, not in black clothes as before, I could enter anywhere.

Vicar General of the Archdiocese of Shkodra

Since some members of the diocesan council had died, Monsignor Çoba completed it, and furthermore, appointed me as Vicar General of the diocese, so I could also administer Confirmation. Even before, I had started performing some religious services when the churches were open, especially in the hospital and the nursing home. The Security (Sigurimi) had learned that I was a priest. And on one occasion, the Branch highlighted an incident we had at home. Gjergji had accidentally met an English tourist, Stefan Vinter, who was embarking on the path to the priesthood. He had asked him for an Office (ofice, likely a devotional book), and my brother, welcoming him home, gave it to him.

Branch Head Feçor Shehu and Xheudet Miloti

The Security had followed him almost to our house. I was not home, nor was I in Shkodra. Immediately, the Security had summoned my brother and me, as soon as I arrived in Shkodra. I presented myself at the Branch as if I knew nothing. The Branch Head, Feçor Shehu, and his employee, Xheudet Miloti, summoned me. After dealing with this incident, seeing that I knew nothing, they told me: you are moving around performing religious services in the hospital, the services were becoming numerous. Even with Dom Kolec Toni, we had managed to organize, without either family knowing where, to perform services, doing baptisms, confessions, communions, and I was even giving some confirmations.

More villagers began to come to the house. The family was a great help to me, especially my brother Gjergji and my sister Çilieta. Never once did I have an obstacle from them; moreover, they had zeal and courage in this missionary work. My sister had a great burden, and she would welcome with pleasure and the smile that characterized her, hundreds of people during the service, and she would coordinate the possibilities of their arrival so that too many people did not gather at once, staying ready at any hour of the day, and even late hours. My brother and sister created very good opportunities for me.

They never told me to be careful, but rather encouraged me, saying: “This is your day to serve.” My brother and sister did everything well and orderly in this difficult period of such holy work. When I went to the villages, I felt very grieved, because there was no priest in those parts. And every time I returned in the evening, I heard those inhabitants saying the Holy Rosary, in a low voice in their homes. In the villages, I was escorted by an attendant, to whom I would give the Holy Eucharist and the holy oils after confession, and he walked in front of me, without anyone realizing that we were together. The greatest danger was when I crossed the bridges, especially the one at Bahçallek, because the police were there! Memorie.al

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)