By Shkëlqim ABAZI

Part forty

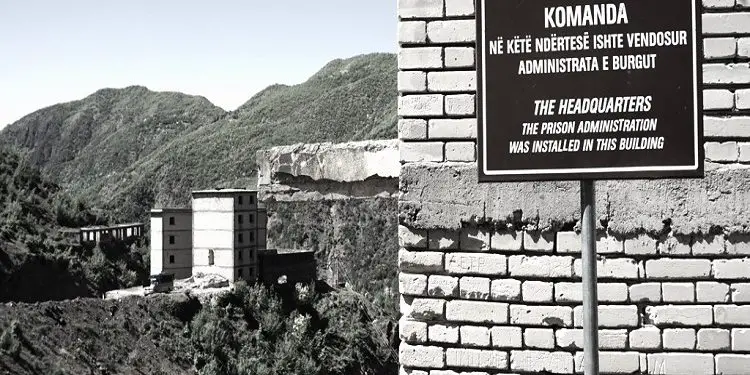

S P A Ç

The Grave of the Living

Tirana, 2018

(My memories and those of others)

Memorie.al /Now in my old age, I feel obliged to tell my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds and of others whose mouths the regime sealed, burying them in nameless pits? In no case do I presume to usurp the monopoly on truth or claim the laurels for an event where I was accidentally present, even though I desperately tried to help my friends, who tactfully and kindly deterred me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you only have two months and a little more left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet, from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months after, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard during those three days; I would not want to take to the grave.

Continued from the previous issue

Xhike’s Carriage

If the turn to try the real auto-prison came in my adolescence, I had the black chance to experience its brother, in the guise of a meat carriage, as a child. A sheet-metal araba crossed my city daily, starting its route at the slaughterhouse, leaving behind the stench of dung, like the muddy cart’s foul smell, taking the road of the vegetable gardens and arriving at the butchers’ shops, which at that time were two, Zengjeli’s and Koçi’s, the former in Çelepias, the latter in the Bazaar.

Usually, the wreck passed at a fixed time, from eight to nine in the summer, and after ten in the winter. Since it crossed that road every day, there was no need to guess who was scratching the quiet; it was enough to open the window and hear the clattering of the sheet metal and the groaning of the wheels splashing through the potholes, accompanied by Xhike’s scream: “Go, father, hey,” which urged the horse to pull, and the whip lashing sometimes the horse’s haunches, sometimes the sheet-metal case.

Xhike was a thin, tall gypsy, around forty at the time. The boisterous carter considered he important, so he strutted atop the seat on the torn goatskin and acted grand and arrogant, overstepping every boundary with his conceit and becoming the cause of frequent quarrels. Strange, even unbelievable, stories circulated about Xhike and the carriage.

The strange ones included some romantic adventures with well-known women in the city, while the unbelievable ones linked them to the carriage. Tongues gossiped that besides distributing meat, tripe, and intestines, two or three times a week, the butchers’ shops also used it for transporting prisoners, from the prison building to the courthouse, which was located a few meters further away, or where the major post-war trials were held in the only hernanë (courthouse/building). While the trial was ongoing, the boisterous carter led the gypsy crowd: “Enemies to the rope!” while the rickety carriage waited behind the door, to take the “infidels” to prison, or to the execution site.

In Berat, with the expression: “May I see you as a groom, in Xhike’s carriage,” they implied: “May you end up in prison,” while the most ominous sentence: “May Xhike take you to Parangua (The Unseen/Hidden),” meant: “May you perish in a nameless grave!” Meat was scarce in those years. Even the few animals slaughtered were sent to military units, to the canteens of dormitories, workers, hospitals, nurseries, kindergartens, the homes of local government leaders, and the highest quality, to the Bloc, for the Leadership.

For the peripheral neighborhoods, inhabited mainly by the poor and the declassed, the offal remained. This was also due to the price, because the meat product remained an unaffordable assortment. With the money for one kilogram, you could buy eight kilos of tripe or intestines. Although they sold them with dung, when you washed them by the river, they still weighed at least three to four times the weight of the meat. Consequently, it was the “poor man’s dish” and somewhat alleviated the poverty that prevailed at the time.

However, not everyone managed to get offal at Zengjeli’s or Koçi’s shop, because the line started from the evening. Just as communism sowed endless poverty, it also bred endless queues. With this diabolical invention, it aimed to exhaust the populace, so they would have no time to deal with other issues, but rather think about how to meet their basic needs. As soon as they returned from work, they were to go to a queue, then from queue to queue, and back to work. This kept their mouths shut and maintained them in perpetual tension.

Old men and women, instead of enjoying their pensions, woke up and went to bed in queues, even dying there; men and women, instead of focusing on the proper education and upbringing of their children, measured the shops inch by inch, to secure a crumb of food, and then, for the minors, they did not use holidays for recreation, like their peers in the world, but became men in queues, prematurely. An anecdote circulated in the city’s alleys about a bride who, instead of worrying about the baby’s health, worried if there was any yogurt left, even in the maternity ward, clutching the umbilical cord with one hand, and an empty bottle with the other.

The populace remained in queues at bakeries for bread, at fountains for water, at dairy shops for yogurt and milk, at markets for vegetables and fruits, at council offices for jobs, at the education section for school, at the hospital for medical visits, at the maternity ward for giving birth, at… for…! Everything in a queue, except the prison and the cemeteries. Communism boasted of abundance and fed the people with the missing dream. Queue, queue, queue…, but the mouth had to be locked; indeed it paid to pretend to be happy because…, the prison was waiting.

While the people spoke, the government filled the prisons.

“No meat or offal!”

“Ten years in prison!”

“No yogurt?”

“Ten years!”

“I want neither meat nor yogurt, I want leeks!”

“None!”

“No leeks either?!”

“Ten years.”

But…, after every epidemic, a saving vaccine is invented. For collective cholera, a collective antidote was found; bribery flourished, favoritism, and corruption erupted. Mouths were locked, and whispers began:

“Want meat, tripe, a loaf of bread? – Connect with Zengjeli or Koçi, but better with Xhike, who supplies them. Want milk, yogurt, cheese, butter, cottage cheese? – Sort it out with Kuli or Dylbera, etc., but more accurately with Rrapi who delivers them. Want a kilo of oil, flour, sugar, rice, etc., – Befriend Pilo and Xhevit, or Isuf, who transports them.”

When you needed half a bread above the ration, they recommended you latch onto Bajame or Shega; for a bundle of wood, you should grovel to Pali; and the story went on endlessly; for a pair of shoes, for cotton cloth, for socks, for underwear, for…, for…, every commodity, even salt, you had to have Dyli as a friend, to give it to you with as little effort as possible. The hierarchy of values was disrupted. The stratum of saleswomen and clerks, previously unknown, emerged.

A saleswoman was equal to the highest official, to an academic, to a university professor, to a city doctor, as no one cared about a village doctor; while a clerk, in terms of reputation, was on par with the deputy of the area, and in terms of wealth, with the highest paid official. Did you have a problem? – talk to the saleswoman; did you want a commodity? – Back to the saleswoman; did you ask for school, a job for your child? – run to the neighborhood saleswoman; was your child unwell? – forget the nurse, go find the saleswoman:

“She is a doctor better than doctors, because she keeps the tools under the counter,” – they would advise you. Imagine if you had her as a wife! No path would be blocked!

“What if you have her as a mistress?” – joked the humorists.

“Oh God, she’ll fill your wallet and fatten your belly!” – the jokers replied. – “But what if you have the clerk?”

“Done and done, heaven awaits you! You can become a cadre chief, director, even first secretary!” What didn’t people do to secure that position: promiscuity, spying, villainy? Manhood lost its feathers, honor and knowledge lost their value…!

“So-and-so’s son (daughter) has done great schooling!” – Some simpleton would boast about the neighborhood boys or girls.

“May he/she enjoy the schooling, he/she will become a village teacher or a poor wretch, if he/she doesn’t end up in oil, or in… a wacko,” etc.

“Hopefully, he/she won’t get stuck in prison!” – the pragmatists would reply.

“What good is education; bless your heart, better to be a saleswoman in a shop than a professor infected with Western culture, a scientist in some institute, a penniless writer, a weird poet, a senile composer!”

Everyone bowed to the saleswoman, for a privilege, and tore each other apart to choose her, when a favor or service was needed. Communism is known as the system that preached power through violent revolution: “Power stems from the barrel of the gun and is defended with the gun!”

While socialism was known for innovations even where exhaustive studies had been conducted: “Let’s rely on our own forces!” “Let’s unleash the creative energies of the talented people,” “let’s open the way for the working class and the cooperativist peasantry to express their innovative abilities!” – ordered the distinguished theoretician, the glorious leader of the world proletarian revolution, Comrade Enver, and the disciples broke their backs to implement these valuable orders in practice.

Therefore, they invented a new profession, unannounced anywhere in the official job organizational charts. The “Queue-Keeper”! Although unknown on any list of professions, it was silently accepted and proved profitable. “When the devil has no work, he plays with him,” they say in Shkodër; but the new devils fell so much in love with the trade that they didn’t rest for a day. In one shop, one person held two or three queues, one for himself; he sold two, to earn a living.

The most agile held queues in many shops at once, at the dairy, at the vegetable shop, at the grocery store, at the butcher’s, at the travel agency, at the cinema box office, the variety show, the sports tickets, etc. Then, according to the importance of the commodity, they set a “reasonable” price: five lekë for the queue at the bakery, five at the dairy, ten at the butcher’s, ten at the vegetable shop, and the price rose, from twenty lekë for intercity bus tickets, cinema, and variety show tickets, up to a hundred lekë at the industrial M.A.P.O. for fabrics, denim, poplin, taffeta, bridal lingerie, and others.

The necessity of helping each other led to the birth of some structured solidarity groups, a queue-keepers’ union, so to speak, which brought forth from its bosom contingents of spies, Sigurimi collaborators, traveling witnesses, profiteers, prostitutes, immoral persons, and professional thieves.

The sense of illegal profit became part of the collective subconscious, so much so that after the nineties, when this trade was devalued and queues remained a bitter memory of the past, scoundrels of this mold began to graze in the informal market of visas, currency, drugs, prostitution, the one hundred and ninety-nine black markets, stimulating and inciting the desperate youth toward uncertain exoduses with all dangerous forms and means.

But not everyone could afford to buy the queues, because they lacked the income, so they would come to the shop in the evening and spend the night there, to be replaced at dawn by the elderly or children. When they went to work, they fell asleep on their feet and sometimes suffered accidents. To maintain some order, they had devised some original methods: they placed stones, bricks, jars, bottles, wooden planks, sacks, etc., and accompanied them with some distinguishing mark.

In our city, where everyone knew everyone, this unwritten agreement was almost respected. But some charlatans who made a living from this trade would arrive before dawn and mess up the queues, changing the position of the bags or stones, causing chaos, where the dog couldn’t tell its owner. They were joined by some gossiping old women, who spoke every obscenity, embarrassing the populace until they gave up their place in the queue.

When Xhike’s carriage appeared, some of his acquaintances, zuska (bold women) and zuzarë (rascals), latched onto it, as well as some doctor or teacher of Zengjeli’s or Koçi’s children, who absolutely needed to be supplied, and certainly the neighboring saleswomen demanded their share, and finally, among others, what remained was divided, if anything remained.

It often happened that Xhike would start for “Çelepias” at Zengjeli’s and end up at “Pazar” (Bazaar), at Koçi’s, or vice versa. One person would signal “he’s gone,” and the marathon began; everyone ran after the cart, from one shop to the other. When they signaled him on the way that the queue where he was headed was even longer, the gypsy would suddenly turn back at Gorica Bridge, and the throng would change direction.

Tired from the endless back-and-forth and sullen from the lack of tripe or intestines, the customers cursed Xhike, damned the horse, and cursed the cart: “Ptooey, damn it, a gypsy ass, making fun of all of Berana!” – thundered the men.

“Ah, may the fire of hell burn you, you consumption-ridden man, along with the horse and the cart, because you scraped the souls off our feet, may your flesh fall off in pieces,” – cursed the women, and the clatter of their wooden clogs on the cobblestones drove you crazy. With these tribulations, you had to get through the week to manage, if you managed to get a share even once. For almost the entire summer, I was part of this marathon with my peers. We performed the ritual out of necessity; we wanted to fill our stomachs, but also secure permission to wash in the river without anyone scolding us.

Mothers or grandmothers woke us up early, spread a crust of bread with some layers of salt, and we held our breath at Zengjeli’s shop, where we squeezed together so as not to end up out of line. In the end, whoever managed to get something shared it with friends so that no one returned empty-handed. But we didn’t succeed every time. Our fate depended on the desire of Xhike, who would sometimes unload half at Zengjeli’s and half at Koçi’s, but when he had less, he would start for one and end up at the other.

At that time, we ran after the carriage “Çelepias” – “Pazar” and vice versa, if not daily, once every two days. In such a situation, an unusual event would occur, where I inadvertently became a witness and an accidental culprit, but which had a good side effect: it saved me from the queue. One morning, a fight broke out between Xhike and a stranger, causing a huge uproar. The police arrested the striker, some women, and me with two friends.

The transportation in Xhike’s carriage, from Zengjeli’s shop to the Department of Internal Affairs, amid the stench of dung and police violence, would accompany me for a long time and leave indelible impressions on my childhood consciousness. At that time, I must have been about ten or eleven years old. When Xhike the bully, who had gotten on our nerves with his favoritism, arrived, I was in line with my peers, as usual. But as soon as he unloaded the offal, he stood at the top of the stairs and looked for his zuska to fill their sacks with tripe and loaves of bread.

That day, too, Xhike the long-shanked, as soon as he finished unloading, stood firmly on the upper step, supposedly to “help” with the smooth running of the queue, while men and women pushed and gasped, exhausted from waiting and the heat. A scream over our heads: “Hey, respect the line,” made us flinch. In front of me was a middle-aged gray-haired man, but I considered adults much older than they really were.

He served as my shield, so as not to end up out of line. Pressed behind him, I almost reached the upper step, when, just as I was rejoicing in my full sack, Xhike thundered: “The tripe is finished!” The commotion erupted. Everyone cursed whatever came to mind, except the man in front of me, who, leaving the line spotted Xhike making a sign to one of his acquaintances. As the customer broke through the barrier with an extended sack, the man changed his mind and returned, snatched the offal from the butcher’s hands, and tossed it onto the counters in a heap.

This gesture caught Xhike off guard. By the time he recovered, the other man had turned his back, but Xhike reached out his arm, stunned, grabbed him by the collar, and cursed him heavily, while with his free hand, he tried to snatch the sack. Finding himself under attack, the other man tightened his straps and wanted to leave, but Xhike dug his fingernails into his throat.

Instantly, the gray-haired man suddenly made a turn, murmured something under his breath, raised his fist, and hit him as hard as his arm could reach, sending the gypsy sprawling onto the sidewalk. I had never imagined this scene, as it was the first time I faced a fight between adults, excluding boxing matches at the city stadium and the squabbles of neighborhood kids. Meanwhile, those present formed a circle around the combatants, forgot their empty sacks, and unanimously encouraged the gray-haired man:

“Hit him, bless your hands! Kill the gypsy; he’s acting like the son of a whore!” The majority cheered for the gray-haired man, and we children also took advantage and kicked his butt, thus venting the long-accumulated frustration. As Xhike groaned, the commotion attracted the attention of passersby who widened the circle and screamed: “Hit him, kill the gypsy…!”

The carter was panting, soaked in blood, on the sidewalk slabs. Meanwhile, the police arrived, who were probably at Estref Kafexhiu’s café, opposite us. Marshal Novruzi and Corporal Pandi seized the aggressor and handcuffed him, then shoved him into the carriage, returned and gathered some women and children, including me and two friends, and crammed us into the carriage. In the darkness, my eyes became wide, while my mind was spinning. I pressed my ear against the door and heard the policemen ordering:

“Straight to the Branch, don’t open it until we arrive!” Then Xhike’s scream: “Go, father, hey,” was followed by the whipping of the lash on the sheet metal and the squeaking of the wheels, like startled hounds.

“May I see you as a groom in Xhike’s carriage?”

I had heard this sentence so many times, but that day it materialized in practice.

A “groom” in Xhike’s carriage!

I had been among policemen before, almost arrested, but the eraser of time had wiped those childhood impressions from my memory. The other times, they had indeed thrown us onto the body of the truck, clothes and all, but our view was unrestricted, and the air abundant; this time they plunged us into a pit, where the stench of dung fouled everything and the stuffiness took your breath away, while swarms of flies buzzed and attacked us wherever they could; in the absence of meat, we became their prey. If you add Xhike’s shouts: “Go, father, hey” and the crackle of the whip on the drum-like metal, plus the curses and wails of the women crammed in with us, the journey became unbearable.

I don’t know how many people were crammed into the carriage, but it weighed heavily and tilted from side to side. After a few minutes that felt like an eternity, the carriage stopped, and the squeaks of the hinges were heard, accompanied by the snorting of the horse. The rattletrap moved another ten meters or so, and then a scratching of a key in the door, and the sheet metal creaked.

When the door opened, we were immediately surrounded by a throng of policemen and blinded by the strong sunlight. We ended up in the prison courtyard, “grooms in Xhike’s carriage.”

“What did these bandits steal, huh?” – the policeman pulled my earlobe and gave me a slap.

“Leave the kids, Comrade Policeman, they didn’t steal anything!” – shouted one of the women who got off with us.

“Give a couple of good ones to those grasshoppers too, Zalo!” – Someone from the shade of the grapevines urged my tormentor. The brush-mustached corporal left me and turned to my friends: “Do you know where you are, huh?”

“No!”

“I’ll teach you, you rascal!” – and he hit the first one as hard as his arm could reach.

“And you, carnation, standing there like a puppet?” – he turned to the other and, without waiting for an answer, slapped his face.

“Leave them alone, policeman, do you have children, or are you a murderer?” – the woman intervened again. The slap reminded me of where I was. Besides the cause of the fight, there were four women, with some rags of dresses stained with dung and faces streaming with tears, the three of us kids, and no other male. As soon as they saw the police, the men ran away; they took the children and the women and brought us “grooms in Xhike’s carriage.”

They beat us senselessly until the police who escorted us arrived, leaning their bicycles against the wall, they spoke something with Xhike who took the carriage outside, took the handcuffed man and confined him under a gate without removing the handcuffs, returned, and scattered us corner by corner of the courtyard, one here, one there, the other further away, so we couldn’t communicate.

When they were done with us, they called the women, put them through another door, from which they emerged a little later, red as peppers. What stories circulated about the Berat prison, about the tortures behind those thick stone walls, which I saw up close that midday! The imposing building sent ice into my bones, while the presence of the policemen terrified me. My childish assumptions reminded me of the chains used to bind criminals, and shivers ran through my heart; cold sweat erupted from my face to my chin, where it picked up the mud of the dung and deposited it on my shirt. Memorie.al