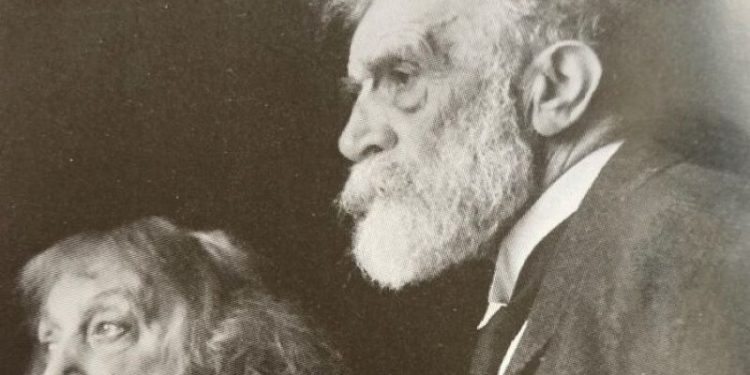

Memorie.al / Besides being a great humanist, scientific anthropologist, and politician who defended Albania in the first decades of the Albanian state’s creation, or as an ardent supporter of Albania’s acceptance into the League of Nations in Geneva, one of the contributions of Eugène Pittard, after his stay in Albania in 1921 and 1924, was his photographic testimony through about two hundred and some plates from the Albanian North and South, photographing ordinary people, Albanian hospitality, historical places, and events. These are views that no longer exist today and serve as a reference for Albanian researchers and anthropologists, ethnographers, and sociologists, to highlight what Albania represented in 1921 or 1924!

If, in 1913, the renowned Swiss photographer Fred Boissonnas photographed Epirus and the Albanian South down to Chameria, Delvina, and Gjirokastra, a mission requested by the Greek Prime Minister Venizelos during the Balkan War and the occupation of Albanian lands in the South, especially Chameria (for which his Greek companion told him nothing about the Muslim or Christian Albanians of Chameria), Eugène Pittard came to Albania with the mission of the international humanist, to help a country fragmented by its neighbors and which needed to be defended in the international arena, as he would specifically do with the Albanian delegation led by Fan Noli in Geneva, for Albania to be accepted as a member of the League of Nations.

Witness to History

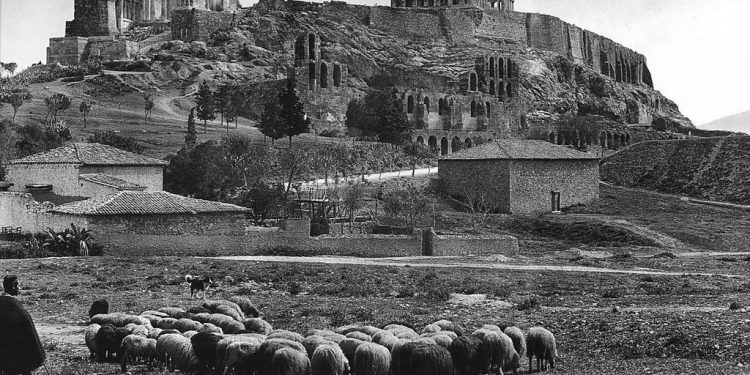

Photography in itself is historical and human testimony, a testimony to the status of a nation and its most fundamental values. The historical importance of Eugène Pittard’s photographs is that he documented not only human images and those of many cities of Albania at that time, of historical, archaeological, cultural, or ethnographic heritage, but also one of the difficult moments of Albanian life during 1921, such as the “Bread Crisis,” which we do not find in our archives in such dimensions with impressive images as his photographs.

What impressed this humanist missionary and delegate for the distribution of aid on behalf of the League of Nations were mostly the touching images of people affected by this crisis, particularly the groups of women with their children. He photographed them mostly in Tirana and Shkodra, but also in the surrounding villages and those in the North like Juban, Koplik, Kastrat, Dibër, and elsewhere. These are faces that do not speak but inherently, in their eyes and stance, possess a kind of stoicism to preserve their dignity, as we see them gathered in the squares and streets of Tirana, in Lezhë, or in the square in front of “Hotel Europa” in Shkodra.

A series of photographs are dedicated to his humanist mission in distributing aid within the framework of the International and Swiss Red Cross, photographs where the Swiss flag particularly stands out, or women holding the aid in their hands. In some of these photographs, Pittard’s wife, the well-known publicist and writer Nowlle Roger, is also present; distributing aid, even clothing, to them. With rare mastery, he also captures images that we no longer find in Albanian archives today. They remain embedded in glass plates or celluloid.

It is enough to look at the photograph of Prince Vid’s Palace in Durrës, destroyed in the bombings of 1918, at the end of World War I, to understand the value of photography as a historical document and reference. And not only that, but also as an artistic value. Similarly, there are photographs of archaeological objects from the Roman period in Durrës or Elbasan, etc., which no longer exist, and which simultaneously attest to his special passion for archaeology and the past life of peoples, and in this case, of the Albanians, even evidence of the Neolithic period that he discovered in Lin, Pogradec.

The Image of a People

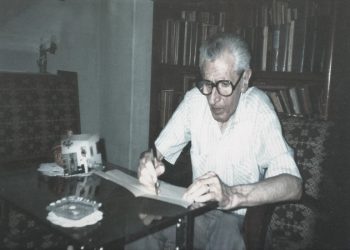

As early as their first visit to Shkodra in 1910, during their stay in the historic city and meetings with numerous personalities of the city, at a time when Pittard did not have his camera, the Swiss couple met the artist Kolë Idromeno, the famous painter and photographer who had called the art of photography “light-writing,” where the light in the camera oscura showed the images of the real world, it was what wrote through light, showing human portraits, objects, landscapes, and the life around.

More than a decade later, in 1921, Eugène Pittard would come with a specific mission. This time he had brought his camera with him, as well as films of various supports along with his tripod or “stativ,” on which the camera was then placed. The purpose was to photograph this country, which was not so well known by the Western world, Europe, and other countries of the globe. This would be the Albania of 1921, or as he might say; “My Albania,” “Mon Albanie.”

One of his first concerns seems to have been photographing the human face, and showing, as an anthropologist, the Albanian face and type, its identity as a people, which not a few travelers, geographers, ethnographers, and French historians had written about their journeys to Albania during the 19th century. But this was also because, first and foremost, the life of the people had to be documented, as the French human geography researcher Jean Bryhnes and his photographer Auguste Léon had done in 1913, photographing for the Albert Kahn Archive the Albanian type and its environment, especially in Tirana, Durrës, in the surrounding villages, or in Chameria and Kosovo.

Pittard’s photographs are truly impressive. It is enough to look closely at the portraits of two Mirdita women, one of whom has a load on her back, staring straight into the lens. These are faces of kindness that have accepted life in the face of difficulties. Their eyes shine with an almost mystical light. An extraordinary photograph where the image speaks volumes about their condition, the strength they have to survive peacefully. Pittard does not forget to photograph their guide, the Albanian roads and itineraries, historical places, places of worship, and the faces of northern refugees who descended all the way to Tirana to escape starvation. Likewise, men from the Albanian South in fustanella, holding children in their arms with a kind of pride.

The message of their gaze and the entire photograph is as if they want to say that we hold hope for a better future. And Pittard approached them very closely with his camera, to bring out their look full of faith. It should be emphasized that Pittard was not one of those who wanted to stage the photographing of the Albanian, with a specific background or decor, as happened at that time even with the Marubi photographers. He was interested in the moment, the face, and the person, to decipher something social: his belonging and the relationship with the land and, moreover, with the drama a people was experiencing.

Many of the photographs have a profound dramatic quality in the faces of those mountain women and solemn men, descendants of a Homeric epic. This social dimension is something new in the photography of the 1920s and 1930s in Albania, a novelty that we will later see in the Italian photographers who came in the late 1930s, and likewise in the Albanian photographers of Shkodra or Korça, who were not satisfied only with studio photographs but went outside, in search of the human face.

The Chronicler

Eugène Pittard was not a professional photographer, as the professionals and famous photographers in Albania were, such as the Marubis or Kolë Idromeno. His Albanian photographs are in nature, which makes him a kind of chronicler who wanted to testify to the Albanian world, the daily life of a people, the Albanians in their dignity, without wanting to be an interpreter of destitution, but to document the Albanian world, urban life, places and events, what he encountered along the way, images that would later constitute historical evidence of Albania at that time.

In everything he photographs, one feels the love of the one photographing behind the camera. He captures the extraordinary welcome the Albanians give him wherever he goes, in Tirana, Elbasan, Vlorë, Shkodër, Gjirokastër, and elsewhere, in the Albanian mountains. The welcome for the Swiss friend is extraordinary. There is a popular enthusiasm in the faces of the Albanian friends, in their traditional hospitality, which is one of their special virtues, and which is also displayed in the dances performed in the squares, to show love for the friend who comes from afar, who is supportive and shows affection for them.

It is a chronicle full of images, where about 200 photographs belong to the journey in 1921 and 37 to the journey in 1924, on glass plates (“plaques de verre”) and on soft negatives (“negativ souple”), images that together, without false staging, show the love of Albanians for great humanists, true friends, their protectors in the international arena, as Pittard was, and for the concrete help in their troubles, to cope with destitution and misery in this period of history, when Albania in Lushnjë was just forming its own government.

As a chronicler, through the photographic lens, he gives space to the frame, gives air not just to capture their arrival, but the atmosphere of Albanian hospitality or the life of this people. Interesting is also the photograph where his wife, Noëlle, stands at the gate of a Berat house, along with the owner of the house after their return from Mount Tomorri, and where the lens has not approached them, simply to capture a personal memory.

For Pittard, it is important to photograph wider, meaning, to capture in the frame, in the foreground, a child and further away villagers with donkeys, or even citizens walking in the street. The moment itself, life, offers this to him. Thus, the photograph gives broader information to the viewer. In the setting of a Tirana bazaar, he captures people, shops, and in the background, the large centuries-old plane tree near a mosque with a raised and severed minaret tower, perhaps from World War I.

Pittard is a traveler who seeks to discover the Albanian world and photograph it. Thus, he photographs the famous building in Durrës of Prince Vid’s government in 1914, which was still standing, but as a ruin, as it had been bombed during World War I, in 1918. It is a surprising photograph that is not found today in Albanian archives or contemporary newspapers.

He likes to photograph traditional and historical houses, the house of the Congress of Lushnja, the Toptani houses, the already ruined castle of Ali Pasha, the one of Këlcyrë from afar, the mosque of Sulejman Pasha, the creator of the city of Tirana, the Orthodox church of Tirana, the monument of Skanderbeg’s tomb in Lezhë, or a ford for crossing the Drin river in Vau i Dejës, where in his notes for this photograph, only the letters “Va” (Ford) remain, as the name has faded.

Rare photographs that today enrich the testimonies about Albania of those years. Also interesting are the photographs of Petrelë, especially the house built on one of the towers of the Byzantine fortress, described by the Byzantine chronicler, Anna Komnena, the daughter of Basileus Alexios of Byzantium, about the wars against the Normans of Robert Guiscard.

Pittard’s Photographs Come to Albania for the First Time

In the collection of the Geneva Ethnographic Museum, there is a collection of 1,055 photographs, taken by Eugène Pittard over a half-century period, in various countries of the world. From this collection, 237 photographs were taken during the visits of 1921 and 1924, which Eugène Pittard made to Albania, accompanied by his wife Hélène Pittard. Eugène and Hélène Pittard began their journey in Albania in 1921, “armed” with pencils, notebooks, and blocks, and guarding their “Kodak Broenie” camera as the apple of their eye.

Their journey, which started by train from Geneva to Rome, from Rome to Bari, and then by ship from Bari to Durrës, should be seen as a journey towards people’s hearts, as a journey into the hearts of Albanians. Pittard’s photographs come to Albania for the first time. The art of photography is an art in itself, and Eugène Pittard has proven this to us best, through his photographs on various supports and dimensions 9 cm. x 12 cm. or, 10.5 cm. x 6.5 cm. as well as on photographic film.

Certainly, his previous travels through the Balkans served him to capture images in the service of science, an experience that helped him perfect himself as a true photographer, getting behind the lens of his camera to photograph people, human types, especially of the Balkan peoples, places, nature, and the very atmosphere of the time in which they lived.

From his photographic collection in Albania, we feel best that he knows how to photograph beautifully, to compose masterfully, to choose what support to photograph nature or portraits with, and within the frame that appears to him, to capture details that serve him to highlight them, adding something human to the image, the person, as we see in a photograph of a centuries-old plane tree in Tirana, somewhat from afar, where a small figure, a child, is in the foreground, which increases the viewer’s feeling towards it.

In the collection of the Geneva Ethnographic Museum, there is a collection of 1,055 photographs taken by Eugène Pittard over a half-century period in various countries of the world. The image. And we like it when the streets and squares are full of people. They are the ones who give life to the image, and for Pittard, this seems to be fundamental. Pittard does not lack a poetic spirit in his photographs.

A wonderful photograph is the one titled “Porte bonheur,” or “Bringer of Fortune,” where a branch rises from a wall on which people have tied strips of cloth or scarves, to express an “ex-voto,” a wish that perhaps fate will realize, an expression of the superstitions that existed at that time, as many foreign travelers, or Albanian folklore anthropologists and scholars testify to us.

Mostly, this poetic spirit is seen in his landscapes, in the flow of rivers and the backgrounds of nature beyond, in Berat or the Vjosa River along the Myzeqe fields, the mountains and mountain ranges of Nemërçkë or Dibër, which are special for a scientist like him, a specialist in human anthropology. Such are the landscapes of the Osum River and the floods on the banks of Berat, with houses raising their heads above the water, which can be compared to the images of the most distinguished photographers of the early 20th century, such as those of the Seine floods in Paris, by Roger-Viollet, etc.

He directed the lens level with the water, which for the time is a rare photographic find, capturing three or four wonderful and unique photographs of their kind in his lens. The other photograph of the floods in the villages of Lezhë is similar, suggesting the relief and geographical position which has extraordinary beauty.

It resembles a black and white tableau, over which a poetic silence stretches, where the beauty of the image conceals the sadness it deeply carries within. In another photograph where the caravan of these travelers has stopped, apparently in the Mbishkodra area, they have sat down to rest for a moment. But Eugène Pittard is focused on photographing, as he likes that scene. He composes the travelers’ rest between two tree trunks where, on one side, are the resting horses, and on the other, Noëlle and their companions, highlanders and military personnel.

It is the sharp and artistic eye of the artist! In the photograph “carriers of timber,” we are dealing with a kind of scene resembling a fresco. Here, too, the carriers have stopped to rest from the long journey. The horses stand silently with their loads, the men with planks in their hands look at the photographer, while three women dressed in black take advantage of the free time to knit wool socks, and a fourth behind them still has the branches tied on her back.

With a mastery of their own, the dancers of Gjirokastra are photographed, who perform the dance upon the arrival of the great humanist, but also in an indoor setting, where the sunlight helps him photograph the movement and graces of the dance, where the fustanella has the elegance of the rush and their manly faces a sense of pride.

They are dancing, not posing; it is a momentary, “instantané” photograph, captured in motion, where the Cajupi Mountain is visible in the background, which makes that group of dancers highly human and full of life. Pittard’s photographs come to Albania for the first time, returning for us to see, the descendants of those Albanians who lived a century ago and were captured on celluloid by the great Swiss friend.

The landscapes and images of the cities have changed now, the progress and emancipation of Albanian society is extraordinary, but these photographs make us reflect on the path traveled by our people over a century, as a reference to the strength, ancient cultural identity, and its desire to integrate into civilized Europe./ Memorie.al