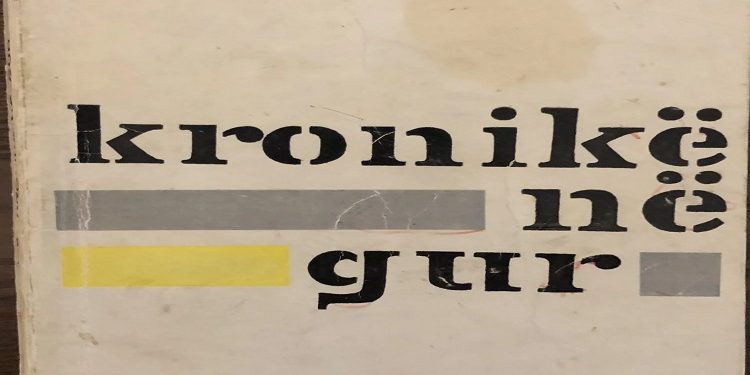

Memorie.al / Undeniably, Ismail Kadare’s work, Chronicle in Stone, has been universally appreciated across all periods. This fact is proven when one sees how this work was received in the United States of America, around 30 years ago. The American daily newspaper dedicates attention to the release of this work, along with some of Kadare’s other works in America. Although very well-known in Europe, the Albanian writer arrives with many mysteries for readers on the other continent. Leonie Caldecott, a journalist who also wrote for British media and was the author of a famous book at the time, penned the article about Kadare’s translated work. The assessments for this book are the result of a detailed understanding of the work, but with little knowledge of Ismail Kadare, the only Albanian writer known in the West.

The Article by Journalist Leonie Caldecott

At the center of Chronicle in Stone is a scenario in which the narrator, a young Albanian boy, during a peripeteia of the Second World War engulfing his city, is taken by his grandfather to visit the house of an inventor. The inventor had claimed to have designed a powerful airplane that operated on the principle of “perpetuum mobile.”

As a resident of a city that had recently begun to face aerial bombardment, the marvelous invention was not only a practical protection but also an “honor” to the people disgraced by the war machine that had been unleashed against them. However, the boy realized that the crumbling, elephant-model contraption represented a hopeless failure.

This perception is based partly on realism and partly on fantasy, which was based on bad times. Every military power is a seemingly continuous threat, such as an Italian bomber that had recently crashed into the old, stone city.

This clash, which the wise and learned elders believed in, is exchanged for the metallic security of modern technology, stripped of all the sorrows of this compelling novel. Ismail Kadare’s insertions into his narrative, in scenes such as this and others, are sure keys to relationships.

The boy’s participation in the world of the magical city and the events that surround him bring to mind the close connection with his grandfather, who acts as a conduit for local gossip, which remains one of the many normal and stable elements in his grandson’s life.

This summarizes everything in the depiction of the strange characters that move in and out of life, such as the yellow-skinned boy who haunts the city’s wells and reservoirs after dark, searching for the body of a girl he loves and who he is convinced was killed by her family after their secret – a passionate embrace during an air raid – was revealed.

The character, through the consciousness of a child with a short adolescence, allows Kadare to blur the line between fact and fantasy, without sacrificing the essential realism of the novel for a moment. The hostile behavior in which the boy perceives his environment, for example, he views water, simultaneously “as a friend and enemy of the stone city,” where “it was not easy to be a child.”

This is precisely essential to the writer’s way of conveying the truth about the situation. Through a level of misunderstanding of things by the child, the events that affect his life – many prejudices from adults – guarantee a foresight that transmits this person’s suffering, more spiritually than any other hope he might entertain. From the beginning of the novel, he and his best friends’ recoil at the sight of the slaughter of animal beings.

Towards the end, the idea of blood has dominated the city more in relation to the hangings, murders, and slaughter of comrades, cousins, and neighbors, which are described with a uniform gaze, inevitably appreciated. As in the scene at the inventor’s house, the children’s state of mind has moved from joy, through boredom, to indifference.

In this way, Kadare has managed to create a narrative that transcends the specific tragedy of Albania. The coming of age of his unnamed narrator stands as a beginning for generations as a whole within the dulled effects of violence.

At the same time, the child is in some sense simply reliving the history of these people, who, from past centuries until now, have experienced conditions arising from countless invasions by armies, from the Italians, the Greeks, and earlier, the Turks.

Even the habits of control conveyed by the Albanian communist partisans bear the same distinguishing marks, in which human sympathy has been sacrificed to ideology rather than justice.

Ismail Kadare’s work (translated into English), which has included poetry and eight other novels, has yet to gain attention in the U.S., while it has been enjoyed in Europe. His narratives have been compared to those of Gabriel García Márquez.

He certainly incites the same ironic suspicion in the understanding of life first, magically, by a child, which is much greater and more realistic than that of adults.

The success of Chronicle in Stone is that it has not found it necessary to deviate from the unification of the aesthetic enjoyment of time, space, and action, realized in this interweaving of realism with fantasy. Memorie.al

Published on January 24, 1988, in the ‘New York Times’

The title is editorial

![“Count Durazzo and Mozart discussed this piece, as a few years prior he had attempted to stage it in the Theaters of Vienna; he even [discussed it] with Rousseau…” / The unknown history of the famous Durazzo family.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/collagemozart_Durazzo-2-350x250.jpg)