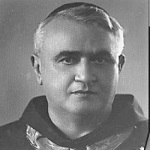

Memorie.al / For us, the descendants, Gjergj Fishta is a distinguished poet, one of the greatest names in this field. His works are published and re-published in these years of his return to the land that had denied him. Scholars and universities are deepening their research and analysis of his works. The most prominent actors recite his poems, recording them on CDs, which are highly sought after.

But perhaps these are not enough to encompass what Gjergj Fishta was in his time. He was a friar, a priest, a teacher, an educator in Franciscan colleges. He was a poet with widely accepted credibility even in his youth. He was a prominent activist of cultural life, standing out for the energy and intelligence of his expression and demeanor. He was a publicist with a sharp and subtle style, with crushing logic, and rich argument and substance.

With these qualities, he had shaped himself into a great character, a referential personality. The ethos, credibility, and character, in these cases as the wealth of a person, transcend a time, a community, an ethnicity, or the nascent face of a new state.

Such characters hand us the features of our identity, tell us who we are, where we come from, and where we must go. This great character, forged early when he was still young, became enriched over time.

Those who came to power after 1944 saw their greatest enemies in great characters like Fishta. They wanted to change the direction of the Albanian identity school with national roots, aiming toward a “new world, a new man.”

Albanian customs and unique behaviors in the birth of children, in weddings, in daily family and community life, in death, in peace and in war, accumulated over years, repeated over thousands of years – these “treasures” were now called backward traditions by the new rulers.

Fishta, mainly with “The Highland Lute” (Lahuta e Malcisë), had depicted the highlander, who as a character was a national asset for Albanians, a highlander who, with his resilience in his own land, with his customs, his clothing, his songs, his towers, with the Albanian language… had remained unalienable in his national features.

He had passed all historical trials and had remained steadfast. A whole generation of knowledgeable clerics had collected the Epos of the Kreshniks (Donat Kurti), had collected the Kanun of Lekë… (Shtjefën Gjeçovi), and had published the Treasures of the Nation (Visaret e Kombit).

In proverbs, in the Kanun, in the Epos of the Kreshniks, the same formulas of language and thought, the same codes of conduct, were repeated. This was a culture consolidated over centuries. It was now being collected and studied. Albanian tradition and the highlander of these regions were almost worshipped by these knowledgeable clerics, at the forefront of whom, with his patriotic action and his prominent literary talent was Fishta.

In the change of course towards the “new world and the new man,” these knowledgeable people had to be blackened and overthrown altogether. They were declared enemies, reactionaries, backward… fascists. Many of them paid with their lives.

In these writings, I will not dwell on Fishta’s poetic creativity. It was a creativity of a Rilindas (National Renaissance figure), within the aesthetic contexts of the time, at the crossroads from Romanticism towards Modernism.

In this writing, I have wanted to emphasize Fishta’s role more as a spirit, as an ethos, as a character. According to culturologists, the mother gives the son the body, and perhaps the mind. The father gives the character, and the destiny, the tomorrow. In mythology, there are sons raised by mothers. At a given time, when they seek identity, character, predetermined destiny, they set out to seek the father. Telemachus sets out in search of Odysseus; Christ seeks the Father, etc. In many cultures, when a man dies, he says; “I am going to my ancestors.”

De Rada with The Great Age (Moti i Madh), Naim with The History of Skanderbeg, Sqiroi (“To the Foreign Land”), Fishta with The Highland Lute, Noli with Skanderbeg as artistic prose (1926) worked to build the myth of the ancestors among Albanians. The Myth of the Homeland. The Epos as a procedure was outdated. But Albanians, like the Jews in modern times when they created their state, needed the golden ages of myths, from which today’s Israel took its symbols, the flag with the Star of David, the Menorah, the language.

Albanians created the state, but they needed historical heroes and living characters, great characters who, as referential figures, would give them spiritual unification.

The heroes of Fishta’s epos are the highlanders of the regions near Shkodra. It does not escape into History. Marash Uci, Oso Kuka, Tringa… even Abdyl Frashëri, is heroes who do not take you deep into the dim epic ages. They are clear, given as living, as if you have them in the palm of your hand. They are the legendary figure of that highlander with a rifle resting on his shoulder who; “for faith and for his own lands/ he spares neither property nor life.”

Zanas, Oras (mountain nymphs, fates), and other mythological figures give depth to the deeds and lives of these heroic men of the highlands. It was this poetic technique, close to the songs of historical epic, but also with figures still alive in memory like Çun Mula, Ali Pasha Gucia, etc., that made Fishta’s poem accessible to all levels of readers. Even to those who could not read, but heard and memorized it, and sang it.

Fishta was a committed activist of the Albanian cause. With drama, with satire, with journalism, he worked for what an organized society in a new state needs to be corrected. Identity is not just a historical given. It must be created and re-formatted every day continuously, in the times we live in. Especially with his satires and journalism, he was strict with the vices of Albanians, his contemporaries.

A state, a nation is founded, but it must be maintained, tempered, and guided towards the good. Fishta was a great character, with an authoritative voice, a thundering and brave denouncer of evils. (“Dirty tricks, buffoons…”). He was a devastating polemicist because of his iron logic; he was profound and enlightened.

During his lifetime, even his opponents recognized his authority, which stemmed from his moral integrity and born talent. Fishta’s national action towards the Albanian of the time was threefold: to discover the identity roots, to cleanse from evil, deformations, vices, and to spiritually ennoble him with school, with poetry, with theatre. / Memorie.al