By Shkëlqim ABAZI

Part three

SPAÇI

– The Grave of the Living –

Tirana, 2018

(My own and others’ memoirs)

Memorie.al / Now in my old age, I feel obliged to confess my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds, and of the others whom the regime silenced and buried in unnamed graves? In no case do I take upon myself to usurp the monopoly of truth or to claim laurels for an event where I was only accidentally present, although I desperately tried to help my friends, who tactfully and kindly avoided me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you have only two months and a little left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months that followed, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard during those three days, I would not want to take to my grave.

Continuation from the previous issue

When I rose up on my elbows, the conspirators cut short their dialogue.

“How do you feel now?” – Osmani leaned over me.

“Better, I think!” – And I made to get up.

“Don’t move, we are here if you need anything! Meet Sezai Turku from Tirana,” – he indicated a man in his thirties, with a dimple in his clean-shaven chin, high-foreheaded, or it just seemed so due to my position and his thinning hair.

When I tried again, Sheziu motioned with his hand: – “If you need anything, tell me!” – And he put the bowl down on the bedding. I thanked him and was swallowed by sleep.

How long did I sleep?

The medicine gave me hallucinations and dreams. It dazed me, and I lost all sense of time. When nature called, I gained control of myself and realized where I was.

I tried to get up, but I felt dizzy. I put on my opinga (peasant shoes) and steadied my step along the side of the second-story bunk, but after two steps, I lost my balance and nearly smashed onto the floor.

Myslim grabbed me by the elbow.

“Thank you!”

“Where are you off to, friend?”

“I need to go to the toilet.”

“Hold onto me, because I am headed there too!”

We took a right after the entrance, and after about ten meters, we found ourselves in front of a barracks on the edge of the abyss.

“Here they are. Shall I accompany you?”

“No, I’m fine,” – and I walked straight ahead.

The latrines were even worse than their twin counterparts in Reps; they reeked of a more disgusting stench, because five hundred men, nearly double the number there, defecated in them. The structure and comfort were no different: two slimy planks for resting the feet and a gigantic hole.

The danger was evident. In Reps, if the footrest broke, at most you would sink into the filth; here, carelessness turned fatal – you would roll towards the perimeter fence, where, even if the soldier’s rifle spared you, you wouldn’t escape without a broken bone.

I finished in the latrine and headed for the taps; from a pipe with more numerous holes, water ran over a reddish basin. The entire area resembled a rust-colored hearth.

“They must have used red cement,” I thought, but later learned it was the effect of sulfuric acid. I threw two handfuls of water on my face and swallowed a few gulps to rinse my mouth, but a pepper-like burning sensation scorched my throat. Nevertheless, the coolness sobered me up, and I reproached myself for the delayed action, but the beating (huri) and the unfamiliar terrain had caused secondary effects.

From the taps, we cut through a barracks where wisps of smoke swirled under the roof, fluttering and descending to the bare walls, distributing a kitchen aroma. On both sides, groups of two or three people were cooking or conversing in front of fire-pits. In Spaç, fires were abundant, because there was no shortage of wood. From the logs used to reinforce the galleries, plenty of scraps remained.

We passed amongst the hosts who were cooking or conversing, as if in a review of honor. Everyone greeted us, and many even addressed me by name. Strange! “In less than five or six hours, they learned who I am! And I thought they were cold and unapproachable?!”

“Oh-u-ah, the world is small, brother! Everything that happens in the orbit of the Albania prison-city is known as soon as it occurs! The socialist pen has no mysteries; it’s an X-ray machine, where you can even see the belongings in another’s stomach!” – Ilia Iljadhi’s words came to mind.

Near the end, Myslim stopped next to a group and introduced me: – “Shkëlqim Abazi from Berat!” “Zef Ashta, from Shkodra!” – a small-statured man, fifty to sixty years old, with expressive gray eyes that stood out prominently on his bony face, extended his hand.

“Skënder Shaholli from Devoll!” – a taller man than the first, with black eyes and black eyebrows, and fashionable mustaches, stood up and yielded his stool to me.

“Ismet Boletini serves you, with Kosovo and the Kosovars!” – said a man with the sharp accent of northern Kosovo.

“Tomor Allajbeu from Peshtan of Berat!” – A man with a stern look, whose thick eyebrows cast a shadow over his eyes.

All four of these names were on the letters of recommendation, or I had heard of them as men of moral value and unyielding resistance.

I greeted them, and we started talking.

After the first acquaintances—the policeman Preng Rrapi, who thrashed me before I could find my footing; Osman Kazazi and Jovan Xhuvani, who treated my wounds; Myslim Fuatllari, who escorted me to the barracks; Naun Bisha and Shezai Turku, my immediate neighbors—these were the presented individuals of the moment.

Thus, in six hours, I met nine prisoners and one policeman, who would be my companions and points of reference in prison.

In the years that followed, I would meet thousands of others, but these would remain the cornerstone of my new connections. Preng Rrapi, the inseparable executioner until the second they would escort me out the door, even up to Zogu’s Bridge; the others, inseparable in prison and outside it; as the case may be, one I would have as a model to follow, one as a professor, but all would become my strong arm in the days, months, and years to come. Together, we would overcome countless hardships in the Spaç abyss.

The Camp

(As I found it, so I left it)

Mirdita Landscape

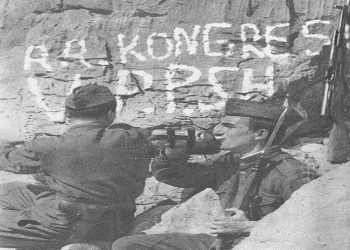

An invisible star that would take the lead for the crimes that would be committed there, for the unparalleled terror, for the experiments and the attempted assassination of the human species, for…; especially for the spirit of sacrifice and the sense of opposition that the idealistic missionaries nurtured, who offered their personality and fueled the lamp of freedom, sacrificed their health and nourished hope for all Albanians, planned the Revolt of May 21, 1973, which the youth carried out, violently embedding itself in the communist constellation.

Behind those wires, the “MEDAL WITH TWO FACES” was hidden: on its bloodied side, the cruelties of the terrorist-cannibal cadres who drove violence to the brink glowed red; on the other, it was the arena for promoting manly character, patriotism, and democratic resistance.

The Mirdita mines have been known since ancient times, but the difficult terrain and the distance from the axes connecting it to the lowlands, plus the primitive means of transport, made it twice as difficult. The Kingdom (Zog’s) undertook some initiatives to build roads, but time, financial shortages, and the unconsolidated order did not allow it. With the installation of communism in the mineral-bearing areas, all kinds of specialists (of Slavic origin, and later Chinese) began to swarm, viewing the Mirdita subsoil as a dairy cow.

Naturally, the greed of the foreigners coincided with that of our own; the former cheaply exploited the minerals for their industry, and the communists pretended to be making investments in the underdeveloped region, supposedly aiming for economic progress and better living conditions. But the opposite resulted: with socialist contrivances, they managed to control the population of the most anti-communist region, they enrolled them in brigades, put secretaries and brigadiers in charge, surrounded them with operatives, and disfigured their character, turning the proud Mirditor, from an unlimited individualist who recognized the Captain of Orosh as his leader, into a mercenary looking for a handout, who fawned over every petty communist rascal.

Mirdita has enjoyed a self-governing status since antiquity, legitimizing the Kanun (Code) and the council of elders (pleqësi e kuvendit të burrave), and above them the Captain, alongside whom stood the Abbot and the parish priests who, over the centuries, have even sacrificed their lives to preserve the traditions and customs of the region with unique values. The invaders, though rarely managing to subdue those lands, were forced to respect the tradition; even the Ottoman Empire recognized their self-governance, facing the stubbornness of these proud types and delegating governmental powers to the Captain – a status quo that ensured peace for the Sublime Porte, and in return, benefited from military forces from the rebellious region.

The Mirditor often lacked bread on the table, but never a rifle on the shoulder and the freedom to wander across and along the borders without having to account for it, a privilege that gave him the sensation of the eagle, soaring from the height of the sky. The Mirditor valued the Captain who protected his political position and physical inviolability, the council of elders who guaranteed his social status, and the parish priest who lightened the burden of his sins, when, God forbid, he committed some act of theft for survival, outside Mirdita’s borders.

The Mirditor traveled with his own shroud. Under the Captain’s flag or in plundering raids, he might fall as a sacrifice, but while the standard-bearer sang his praises, the Abbot offered him paradise, and the parish priest cared for the orphans with parental devotion.

The living conditions had made him stubborn, and he viewed himself as equal among equals, which is why he addressed everyone as “or tëj” (you there/hey you), using the formal second-person plural (“ju”) only for groups.

Educated with a sense of unconditional loyalty to the Captain, blindly submissive before the decisions of the council of elders, infinitely obedient to the friar’s wisdom – qualities that are quite debatable – the Mirditor became a willing sacrifice.

These vices-virtues aroused the greed of the rulers; even the Pasha of Janina formed his guard with these rascals, ready for sublime sacrifices. Simply to justify the financier’s trust and to preserve the region’s name unsullied, or out of caprice, those proud types performed heroic and naive deeds that happened nowhere else in the modern world.

History provides us with examples of unparalleled resistance and heroism.

I refer to two tales from the turn of the nineteenth century:

The first is from Doctor Astrit Delvina, about an incident in Janina:

“A guardsman of Ali Pasha was shaking from a toothache. He wrapped his jaw with the turban around his head and rushed into the waiting room of the surgeon, along with a friend. The Mirditors burst into the study, as they considered it shameful to wait their turn. The dentist, seeing these chaotic rascals, without a trace of etiquette and dressed differently from the local inhabitants, became anxious.

‘Exo apo dho, chi…Chi..kyrie stratiotis’ (Out of here, sir soldier)! – He shouted at them, because he didn’t understand the northern dialect, and didn’t even speak Tosk dialect well.

But the soldiers didn’t budge. The jaw-wrapped man glared at him. Terrified, the dentist showed him a semi-reclining couch:

‘Edho. Ti echis chi… Chi… kyrie stratiotis?’ (Here. You have what, sir soldier?) – He invited, with trembling lips.

‘What is he saying, hey you?’ – The wide-eyed one turned to his friend. – ‘Tell the gentleman that we didn’t come here to get screwed, or for anyone to screw us!’ – And he immediately put his hand on his pistol.

The doctor dropped his pliers and ran out. An Albanian who was waiting intervened and served as a translator until the situation calmed down.

The doctor couldn’t compose himself, so to get rid of these reckless rascals as quickly as possible, he spotted the ailing molar and pulled it out without anesthesia (at that time, there was no talk of anesthesia, perhaps simple numbing with ice, doses of rakia, or alcohol.) Blood splattered the floor, screams rose to the sky, the pain blinded the palikar’s judgment, which let go of his pistol and turned into a crying wretch.

This metamorphosis caused hilarity. The onlookers began to mock, but the companion, hurt in his Mirditor pride, grabbed the surgeon by the collar, opened his mouth, and signaled him to pull out any tooth he wished. The surgeon recoiled; the teeth and molars in the other’s mouth were healthy, like a wolf’s fangs.

“Pull it; what are you waiting for, man!” – The soldier hissed at him.

“What are you doing, comrade, let’s go!” – Despite the severe pain, the bloodied man took his arm.

“No, honestly, I’m not leaving without showing this dirty Greek and these ragged Tosks what a Mirditor is capable of doing!” – He violently forced the pliers into his mouth and put his hand on his pistol: – “Quickly, or by God, you will…!”

The soldier’s insistence sealed his fate. The surgeon didn’t delay, but pulled out the first tooth the pliers gripped. Although blood burst forth, not a single “oh” or “ah” came out of the soldier’s mouth, which left high-headed and proud, for the honor restored.

Sabri Godo mentions a manlier episode in “Ali Pasha Tepelena.” The Mirditor soldier refused to lay hands on disarmed men, women, and children.

The leader of the punitive detachment, of the forces that subdued the Kardhiqots, opponents of Ali Pasha, refused to shame the bound men. “Pasha, my Lord, give them a rifle each and we will fight like men, in the field of battle!” he replied.

Communist “Goodness”

In the early sixties, the communists built the factories of Rubik and Laç, with free labor. As raw material, one used copper, the other pyrite, minerals that the Mirdita subsoil concealed.

The Mirdita subsoil is rich everywhere, but Gurth-Spaç stands out. In the same mountain and on the same slope, half has pyrite mineral and half copper.

Since the distance of the mineral-bearing zone to the location where they installed the factories was not too great, they built some makeshift roads, but the workforce was expensive, and the cost increased considerably. Even at the risk of life and health, the population around the mines was abandoning the villages, because it was more profitable for them to work underground than toiling for thirty lek in cooperatives.

They planned the Spaç camp to stop the hemorrhage. They engaged specialists from all institutions, even the Prime Minister, as I mentioned above. The terrain and position were perfect for exploiting the free labor of political opponents cheaply and far from the public eye. Meanwhile, they also employed local police and miners. Thus, they killed two birds with one stone: they crushed the enemies with the fear of being lost in these pits, and they brought the prison to the door of the locals, as if to say: “bow your heads and don’t make a sound, because here is hell.” This way, they undermined their character and made them hostile to each other.

They erected some stalls in the Soviet style, surrounded them with mud/clay, threw some eternit slabs on top – where whatever fell outside flowed inside – and housed the politicians.

Oh God, if you were to dig in the darkest corners of hell, you would hardly encounter such a panorama!

I don’t know which “architect” thought of installing the camp on that landslide?! If I knew, I would propose an initiative for a “Nobel Prize,” as a contribution to medical science and an experiment with the human species, in conditions of a stall regime, lacking parameters for a miserable existence.

Plenty of air, without quality water, with humidity far exceeding the norm in winter and scorching heat in summer; (perhaps he calculated to induce rheumatism in the heat of summer). Therefore, even after death, he should be proposed for the Nordic prize, even if the rules of the Swedish academy are slightly violated, because not everyone has contributed in this way, in the field of survival.

Let’s leave the architect and move to his infernal project, to the Spaç I found. – Memorie.al