By Shkëlqim ABAZI

Part two

SPAÇI

– The Grave of the Living –

Tirana, 2018

(My own and others’ memoirs)

Memorie.al / Now in my old age, I feel obliged to confess my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds, and of the others whom the regime silenced and buried in unnamed graves? In no case do I take upon myself to usurp the monopoly of truth or to claim laurels for an event where I was only accidentally present, although I desperately tried to help my friends, who tactfully and kindly avoided me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you have only two months and a little left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months that followed, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard during those three days, I would not want to take to my grave.

Continuation from the previous issue

Friends helped us to the entrance, where we climbed onto the truck, tossed the beams onto the open-bed of a “Skoda“ (truck), which slipped out, shaking. Soon, it was replaced by another with a super-high bed and a tarpaulin tent over the box. The heat intensified and sweat streamed in rivulets, making our shirts stick to our bodies, while from the megaphone’s funnel burst forth cries of hell, more scorching than the rays: “Imperialist-revisionist enemies, will leave their bones on the Arberian shores! The Party and comrade Enver Hoxha, will set their border at the dogwood tree…! Hurray-a-a…!” The sounds pierced our ears, coming from the guardhouse by the gate. “Ptu-h, not even the peak of the heat shuts the mouth of these damned ones!” – said Esat Kala, and spat a thick glob of phlegm.

“Save your secretions, Esat, my boy, or your throat will dry up!” – teased Shyqi, always quick-witted (hazër-xhevap). “They curse everyone, enemies here and enemies there, as if they were the gold of the world! He who curses, gets cursed, my friend! But the Devil, when he has no work, plays with his own bird!” “Will you shut up there, or…!” – threatened the internal guard.

The sweat continued its flow, as the sun solidified in the celestial dome, as if bound with shackles. “Socialism will win!” “The rays of the Far East shall have no sunset!” “The great Helmsman, comrade Mao, will destroy the capitalist-revisionist camp…!” “Our alliance will win! Hurray-a!” roared the funnel. “They’ve even shackled the sun, by God!” – Shtjefën Lacuku was stunned. “What else is left now?” – Shyqi provoked him. “Only the devil with horns!” – Tefa replied.

“The Devil doesn’t shackle the Devil, trust me!” – Someone philosophized. The others fell silent.

“Shut up or I’ll put the irons on you!” – The policeman threatened again. “Oh, please, we’ve been waiting for those for two hours now!” – mocked Esati. “Your soul will leave you right here, you fool, in the scorching sun!” – threatened the policeman. One hour in the scorching heat, we drained our canteens and were drenched in sweat. The hardships were part of the Sigurimi’s tactics, applied to push the enemies’ patience to the brink. Such were the sudden inspections, the repeated roll calls, the endless lineups when we returned exhausted to death from work; during the winter frosts, the summer scorch, wherever and whenever the opportunity presented itself. Around noon, a cluster of policemen showed up, taunting:

“Look how powdered the guests are!” “They’re getting ready for a wedding, comrade!” “Where’s the groom, then?” “They’re all grooms, friend!”

The officer of the guard cut short their teasing and started the roll call. Whoever’s name was called was seized by the nearest policeman, handcuffed, and shoved onto the truck bed. When I was called, “Mark the mustachioed”, he grabbed me by the elbow, put the handcuffs on, but didn’t push the clasp to zero, and helped me onto the platform. I was among the first; my spot fell behind the cabin, and when the vehicle set off, starting to rattle, I leaned against the side and wasn’t tossed around like the friends in the middle. While they suffered the pains of the joints, even before we started, I thanked Mark with a nod of the head, which he noticed, and moved the tip of his yellow mustache slightly, contriving an ironic smile.

Once we were on top, they shackled us a second time with a chain and made us into a single body, so that when one was pulled, the others were dragged along.

After two hours in the scorching sun, the tarpaulin heated up, as if the world was on fire. When the heap (the truck) started rattling, a puff of smoke saturated with unburnt fuel ballooned and swelled the cover. The gas took our breath away until the end of the journey. From the “Murdallëk” to hell! The truck jerked back and forth, gained speed, crossed the wires, and veered left. Suddenly, I fixed my eyes on the back wall and saw the place where I had spent almost two years. Because of the tarpaulin that hid the side views, one couldn’t see much, but the scene still provoked disgust in me. Perhaps my feelings had been flattened somewhere in the extreme corners of my subconscious, and I couldn’t perceive reality.

This place was “murdallëk” (filth/hellhole)!

I agreed with old Esheref and tried to erase it from my memory, if possible, even from my cerebral hemisphere. This “murdallëk” had only imprinted suffering, pain, and calamities on the celluloid of my memory.

I remembered the bitter cold of the first evening, the “Golgotha” pillar where they tied me with wire, the needles of rain that pierced my face, the freezing cold of the solitary cells, the roaring of the Fan’s gorge, the heat, and the asphyxiating dust. My gorge heaved, and I cursed that piece of territory with all my soul:

“May your name vanish, oh ‘Murdallëk’, may I never see your color, for life eternal!” Besides contempt, my friends appeared to me, parading as in a macabre procession; one suffered from paralysis, the other from mental mutilation, someone else lost everything—body, mind, and life. The distorted face of Meleq Hasa, disfigured to ugliness, appeared to me; Nuri Abazi, with the cavern that would take his life; Dom Mark Hasi, who would be tormented by asthmatic breathing until his last moment; and especially Kosta R., who would wander around picking up toilet maggots. The shrunken phantom of Barba Jorgji also appeared, and I cursed again: “May your name vanish, oh ‘Murdallëk’, may I never see your color for life eternal!”

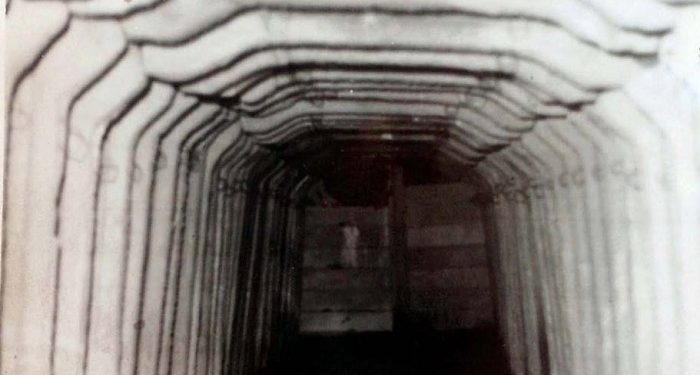

The engine gasped, mixing the smoke with the road dust that covered the bareness of the back bed and penetrated our lungs. I strained to catch a piece of the landscape, but my eyes burned, as if someone had thrown a handful of sand at me, while the sweat streaming down the furrows of my forehead rose slightly above my eyebrows and slid down the corners. I squeezed my eyelids shut and immersed myself in dreams, but my imagination worked backwards. We were traveling at noon, but the view was black and dark, like a cubist painting. However much I tried to imagine the place awaiting us, my fantasy produced a gloomy image, painted with the color of darkness, until I envisioned a plateau surrounded by barbed-wire fences, where pieces of night fluttered with the tongues of harpies, over the head of the devil, while the searchlights tore the darkness with arrows of light and crossed the wires, casting a false aura on the horizon. In the ravines, some holes opened like the jaws of hydras (lëfyte kuçedrash), waiting to swallow us in their insatiable guts.

This view shook me beyond imagination; it surpassed the reproduction of the black picture with thick brushstrokes, which my friends who had trodden there earlier had described to me. The weakness of my imagination, which failed to encompass the corners of the devil’s den, far more murderous than tales of witches and vampires, I would realize only when I faced the reality. That’s when I believed Dante and his hell.

After every pothole, the truck jumped, and we swayed and leaned left-right under the weight of the chain. The buzzing of the engine and the clanking of the links portended doom, while the gas and road dust took our breath away. The yellowish dust didn’t leave us until the truck stopped.

The rattling and swaying of the truck bed gave a sense of the terrain.

On the climbs, the truck howled mournfully and advanced with difficulty, struggling and straining like a stubborn horse when changing gears, while on the descent, the noise subsided; the front row hung downwards and bore the weight of the others. We covered only six or seven kilometers as the crow flies, but the winding bends along the streams quadrupled the distance, which I would understand three years later when I would pass by there.

Devil’s Welcome!

“Move it from that place there, or are you waiting to be greeted with drums?!” With these words, the first policeman greeted us, at the first stop, the first gate, on the first terrace. “Where are we?” “In Spaç, friend!” “You said ‘S’paç’ (Did not have)!” “In S’p-l-aç (Not pleasing), may you both burst!” A bunch of policemen burst into laughter; our miserable sight seemed to remind them of some hilarious sketch that made them melt into hysterics. I don’t know if they were afraid that, as uninvited guests, we might occupy a corner, but we were uninvited and unwilling guests at that macabre wedding. We were the advance guard of a shackled army that would be confined here a few months later. “How nice, just like they came out of the cocoon!” – One policeman mocked. “They brought him to Prenga’s path, for the ideal!” – Another chimed in. “Is this how you greet guests, Prengë?” – they teased the “host.” “Quickly, jump down, you filth!” – Prenga bellowed. Taunts and more taunts, irony followed us at every prison gate!

His colleagues egged on the brute Prenga, but we bore the brunt of it. He scrambled onto the truck bed and shouted furiously: “Jump down, there!” – He gave us a push, without considering the chain in which we were shackled. The first ones pulled the second, those others, and head-over-heels, onto the wooden benches, there was a catastrophe of human bodies, where the head of one was entangled with the feet of another. “Ha-ha, hu-hu,” the policemen cackled, while a group of convicts waiting to replace us on the truck bed were horrified. “Down there, or by Go… the party’s ideal, you will pay dearly!” – He shouted at me in a rage. I expected many bad things, but I hadn’t imagined this calamity of shouts and screams, plus the humorous excesses of the police troop, which convinced me of the extent of collective madness and state cynicism, which turned people into beasts. “I can’t stand your face, you mongrel!” – His words were followed by a whip crack on my back.

I don’t know if it was a curse or bad luck followed me at every prison door; as soon as I got off at Reps, I ate a few rubber truncheons; at Burrel, I ended up in solitary confinement with mice, for a trivial misunderstanding, and in Spaç, God knows what awaited me! I tried to free myself from the chain, but the turmoil tightened it even more. A second whip crack and my shirt stuck to my body, and two blows followed the first, and a roar:

“You there, who do you, want to mock with your face?” – Without giving me time, two more consecutive blows. I was stunned. “Prengë, they are tied to the chain, you there!” – Someone intervened from afar. “Mark, look at the villain, they are enemies of the party!” – Yet another whip crack, more bitter than the first ones. “You must remove the padlocks, friend…”! – More intervention from the group. “Look at this scoundrel, who wants to play games with us!” – Another whip crack.

“What are you doing, Prengë?!” – One of the Reps policemen took out the bunch of keys, fumbling in and out of the padlocks until he found the suitable one.

The “confusion” prolonged the suffering; the chain was so tightly tangled that they couldn’t find the end. “This sneak wants to play with us, you there!” – Another whip crack. The heat and thirst increased my suffering so much that my legs wouldn’t hold me, while my back burned terribly, my shirt stuck to my flesh. I don’t know who else besides me got caught in the wave of blows, but they were all aroused, covered in blood. Whoever escaped the handcuffs avoided the “host.” I tried too, but Shyqi stopped me:

“You’re drenched, man; let me wipe your back!” – He pulled up my shirt, but the cloth was stuck to my skin. “These infidels have mutilated you!” – And he wiped me with the corner of his cap.

“Throw those legs down, there, or do you want a Mirdita stake (hu mirditorçe)?” – The policeman threatened. Shyqi started to turn back, but I stopped him: “Let’s go, I’ll treat it inside!” – And we headed towards the bundle of clothes that were piled up amidst the dust. I threw it over my shoulder and followed the others up some steep steps. The intellectual level and the confrontation with the police savagery would convince me that communist ideology corrupted the slave, while propaganda brainwashed them and reduced them to a seven-headed hydra. But in conditions of misery, I also encountered the contrast to evil, the humanist idealists and unbreakable resistors who opposed social evil.

But let’s leave that for the future and return to the day of arrival.

I descended the stairs dug into the earth and found myself immediately in a plain half the size of the Reps square. Waiting for someone to orient me, my knees gave way; I threw the load under the shade of an acacia tree and waited. A strange metamorphosis: dozens passed by and no one cast an eye on me. Two years ago, many hands reached out to me, but now that I claimed to be a seasoned prisoner and should surely be known, everyone was moving away from me. “What is this coldness?” I almost cried out, when I saw myself abandoned, but I held my teeth tight.

Later, I would understand that the reason was not coldness or malice, but the wretched state they reduced me to. They took me for a quarrelsome or psychopath, and usually, everyone avoided troublesome types. As soon as I lit a cigarette, my vision blurred and I fell into the arms of Lethe (oblivion). As if in a daze, I heard my name. Was I dreaming? When the call was repeated, I opened my eyes. Two strangers stood close by, so I tried to stand up, but my back stabbed me: “Oh God! Don’t move, let us treat you here, then we’ll go to the barrack!” A blond man in his fifties, bent like a scythe and thin as a question mark, leaned over me. The other was rummaging in a leather bag.

“Maybe they are the doctor and the nurse, who were informed by the friends from Reps!” The older man pulled off my shirt: “They’ve mutilated you, may their faces turn black!” – Perhaps the welts were bruised and noticeable. “They’ve torn him to pieces, Vani!” – He turned to his companion. The other dipped a swab in hydrogen peroxide and washed my back. Oh God, it burned as if they were stripping my skin! With gritted teeth, I remembered the unknown man’s sentence in the solitary cells of Shkodra: “Hold on, Çim my boy, now you will shed seven skins in prison, if you manage to come out on top, if you have that luck,” but he himself didn’t remember me! As soon as they finished the bandaging, I offered them a cigarette, but they didn’t accept it. The older man sat down next to me and introduced himself: “Osman Kazazi, from Tirana, this is Jovan Xhuvani from Elbasan,” – the names reminded me of the letters under the soles, and when I tried to take off my peasant shoes, Osmani stopped me: “There’s no need, you didn’t come alone, my friend!”

“Shkëlqim Abazi, the most unknown prisoner in Albania,” – the way they received me led me to think that no one knew me! “The friends from Reps told us,” – the older man interrupted me. “Thank you for being here for me!” “What’s that word, we feel bad that this trouble found you!” “Anyway, thank you, I consider this a gift from the communists.” “The way they treat young people is saddening,” – the nurse intervened and handed me a blue pill. “What can you expect from the brainwashed, damn it!” – Osman continued. “But the sea is salty everywhere!” “Lal, you need to find your spot, because the medicine is working now!” – The nurse interrupted him.

“We found it next to Shezi and Bisha. Come, Myslim!” – He invited a dark-mustachioed man in his thirties, who extended his hand with a smile: “Myslim Fuatllari, from Pogradec!” – And threw the bedding over his back and headed down without waiting for an answer. He entered a barracks on the right side of the slope, where the stench of coal dust and the wet rags freshly taken out of the boots suffocated you. As I walked, I glanced at the dormitory. The extremely steep position of the terrain made it similar to the deepest circle of hell, but it was no different from the Reps ones, with the same dimensions and the two-story bunks made of beech wood. Even the residents were Siamese twins of Reps, shaven-headed, weak, thin, and dirty. The only difference was related to the age; there were many young people and few elderly; (out of about five hundred people, over four hundred were from eighteen to fifty years old and the remainder above this age).

The mines required strong slaves. The State Security had put this trick into practice; whenever the structure needed improvement, they undertook waves of selective arrests, brought in young people, while the elderly and the sick were exploited on the surface until their strength was exhausted, and then they were banished to spend their days in other camps, or in Burrel prison.

But this belongs to a separate chapter.

An Unusual Neighbor…!

Near the end, Myslim stopped, threw the load onto a vacant space where I was to be settled “for the moment,” but circumstances led me to spend over two years there, although my neighbors changed several times. He introduced me to my immediate neighbor, Naun Bisha, from the villages of Kolonjë, while I would see the other one when the shift returned. Naun, the stocky and taciturn man, was considered simple-minded, but having him as a neighbor for several months, I confirm the opposite. He truly was an incorrigible individualist, but by no means simple-minded, as people cited: “This Bisha is simple-minded in his thoughts, simple-minded in his cleanliness, simple-minded in his orderliness, with an excess of pride and belly; meaning, humble yet proud!” According to this, it meant that I left one Luigj in Reps and found another in Spaç. No. Naun was not Luigj, who counted his bites and wouldn’t move without getting his share; sine qua non. He consumed himself and wouldn’t accept anything. The jokesters called him “Bishë” (Beast/Wolf), a pun on his surname.

Naturally, he didn’t bother anyone, because this epithet suited his character perfectly. Naun was a prototype of extremes. In fact, opposites were intertwined in him; he respected and hated immensely, he tended to oppose everyone, to categorically resist even when he was wrong. So, this flawed man measured and cut according to his own mold, he had a distinct notion of honor and a different perspective on character; he hated spies, to the point of disgust, he despised the immoral, to the point of rage, and he opposed communism, to the point of madness. He demonstrated such extremism for cleanliness, which he said was superfluous in prison; he considered books a luxury for gentlemen; and art, a shield for the weak. For obstruction with communists, spies, and the immoral, he appeared extremist, even in his religious faith.

Unique, even strange, he became illogical; he didn’t judge the circumstances that determined the deformation of a character. The phrases: “immoral people on the rope, spies by the bullet, communists on the guillotine, and atheists on the stake!” had become a legend. He didn’t care that someone had chosen to become a communist, with the naive conviction that this way he was serving the nation and society better; he considered him perverse; that extreme violence or the threat of execution had influenced the submission of a spy; he judged him weak; that someone had been violated and then led into the path of baseness with baseness; he called him unworthy; that an atheist or agnostic could be as useful as an atheist; he didn’t take it into consideration and registered him as a servant of Lucifer.

He saw the unique solution as the rope, the bullet, the guillotine, and the stake! His philosophy was summarized in the sentence: “Either night, or day, either black, or white, either wet, or dry; there will never be intermediates!”

That’s why he was considered deficient, but I don’t agree with this conclusion; I attribute the qualities of a contrary person to the spirit of contradiction that dominated his character, mentality, and perception of the political-social phenomena of the time. For almost two months, I didn’t observe any signs of depression or mental illness, except for nihilism and deep individualism, unparalleled stubbornness and intransigence. I didn’t hear that he had accepted anything to be forgiven to him, but I considered this vice-virtue strength of character.

When my family visited me for the first time, I attempted to invite him, but as soon as he heard about lunch, he grabbed the blanket and pretended to be sleeping, under the shade of the acacia. I left him his share. After the guests left, I lay down to get some sleep. He returned, but remained doubtful when he found the bowl covered with cement paper on the bed. I cannot explain the contradiction of his conscience, but it seems the feeling of friendship overcame his stubbornness, because he reached out his hand, removed the paper, but didn’t put anything in his mouth, although he was always hungry. He looked at me and at the bowl, uncovered it and covered it again, and again looked at me. From under the blanket, I followed the scene; I decided to uncover my head when I saw him torturing himself.

But he, apparently, had waited, because he covered the bowl and turned to me: “You’re ruining my character, Çim brother!” “No, Nuni, I believe I have a good friend and…!” “I think the same, but this matter is tricky; once the mouse gets into your mustache, and then tries to block its path!” – He moved his finger under his nose. I took the gesture as a prelude to refusal: “We have been neighbors for weeks and haven’t exchanged a single thing. After all, what would we exchange? We only had soup. This little thing is not enough for you or me; we just wet our mouths, because tomorrow we have the cauldron again. Don’t refuse, please!”

He fixed his gaze on my eyeballs; I thought he would refuse, but I was wrong from my haste to draw quick conclusions. “You convinced me, lie down now!” – He ordered. I covered my head, because I didn’t want to make him uncomfortable. Perhaps I was among the few who broke the ice of the unusual custom, which my friends confirmed to me; I turned out to be the first in ten years of prison that Nuni didn’t refuse. Until he was taken to Burrel, we had a perfect relationship; of course, I respected the parameters he considered non-negotiable. However difficult he was due to his famous extremities, I preserve the memory of an individual with positive premises.

The Reddened Shirt and Black Blood

I spread the bedding over the specially prepared empty space and was arranging the books on the shelf above my head. “You brought quite a lot of books and notebooks, friend!” – Naun said behind my back. “I can’t do without them, because I’ve started my studies!” – I justified myself and continued without losing my composure. “My boy, these are superfluous in prison!” – I didn’t know how to take it, as a reprimand or a mockery. “I barely managed to secure them!” – I replied casually. “Ah-ah, you’ve started well, brother!” – And he leaned on the pillow. I want to emphasize that my spot fell on the first floor, where every action was done hunched over. The bloodstained shirt drew the attention of others. “You’re scaring us with that shirt!” – Someone from across the corridor spoke. “Oh, please, this red color has become so much… that we’re willing to squeeze the blood out of our bodies!” – added another. “Leave the boy to his own trouble!” – Naun cut them off. “What a surrealist painting you have on your back, you’re going to shake the world! Ha-ha-a-ah!” – Someone further away cackled.

“Shut up, you fool!” – My neighbor snapped at him. They fell silent for a moment, but started again. “It’s blood, what did you expect to see?” – my neighbor defended me. “This red color scares us, you poor thing!” – Someone alluded to communism. “Do you want black, then?” “Well, we say the communists, their blood is pitch-black and their soul is tar! But this one has the color of the flag, you dear man!” – Naun concluded his apology. Despite the rhetoric, I undressed, and what did I see! The shirt on my back had dried to a crust; those who begged me to take it off were right. “U-a-a-ah, but he’s just skin and bones, as if the gravediggers took him from their hands!” – cried the one whom Nuni called “fool” and added: “Hang it on the pillar to scare the magpies, man!” I took a shirt out of the sack, but Naun stopped me: “Wait! You truly have a danger-death tattoo embroidered on you, like on electrical plants, friend!” “What is there to see, Bisha! Let the other man get dressed,” – Myslim scolded him from the bed opposite. “Lym brother, the stake thickens the skin, trains the patience, and strengthens the character!” – Nuni mocked: “But he just started, friend, in Spaç, the snake sheds seven skins, let alone a man!”

I was troubled; it seems the nurse’s pill started its effect because my eyes closed and I lost myself in oblivion. Dream and oblivion. “Damn! Once an unknown man in the solitary cells of Shkodra told me: ‘Hold on, Çim my boy, now you will shed seven skins in prison, if you manage to come out on top, if you have that luck!’, while this one here says it differently: ‘In Spaç, the snake sheds seven skins, let alone a man!'” A bunch of snakes writhed around a heap of freshly slaughtered meat, their bulging eyes biting and chewing with their forked teeth dripping venom, until they stripped the bone. Oh God, the long-tongued harpies are sucking the vital fluid! From the pile of meat, a bloodied body appeared, shrinking from pain. I snapped at the pack to save the wretch, and what did I see? The naked, torn-up flesh was me! “You here?” – The pile of meat spoke to me. “I’m trying to help you!” – I replied. “You are trying in vain, poor wretch!” “In the hell they put me in, I will shed seven skins!” “Are you me, or am I your ego?”

“I’m not interested in the affairs of that world!” – He widened his eyes until they bulged out of their sockets.

“Will we manage to be saved?” – I asked, trembling.

“The Devil knows, we just shed the second skin!” – He added, terrified. “The second, you said?”

“We have five more left!” “Oh God, five more!” – I was startled.

“In Spaç, the snake sheds seven skins, let alone a man!” My back burned to death.

“Shezo, I brought this new friend!” – A voice that seemed familiar woke me up.

The second, unknown: “Which one, Lal?”

The first: “This man from Berat, whom the friends from Reps entrusted to us.”

The second: “Which ones did you say?”

The first: “From Esheref Zajmi, Daut Runa, Izet Gumeni, Raqka Prifti, Dom Mark Hasi, Father Zefi, all the way to Refat the tinker.”

The second: “I understand!”

The first: “He needs our friends’ support too.”

The second: “Don’t worry, it’s done!” – Memorie.al