By Dr. LAURENT BICA

Part One

Memorie.al / I must not have been more than 5-6 years old. I am sure of one thing: I hadn’t started school yet. My mother, my late mother, taught me numbers and the letters of the Albanian alphabet in a notebook she had found, who knows where. It was the 1950s, difficult years after World War II. She told me that she had done her elementary schooling during King Zog’s time, around 1935, in a village in Opar, Lavdar, which was the central village of the same-named commune, Opar. She herself would go there every day from the village of Karbanjoz, along with her sister. Every day, before class started, all the elementary students, which at that time had five grades, would sing a song that was sung in all the schools of the Albanian Kingdom, which contained these verses: “And the red and black flag / Will wave again / In Kosovo and Chameria.”

“Kosovo and Chameria are parts of Albania,” my dear mother would tell me. “Kosovo was taken from us by the Serbs, by Yugoslavia, while Chameria was seized by the Greeks. Kosovo is as big as Albania, and Chameria is not small either.” She would then take out of her “archives,” the drawers of the cabinet, all sorts of writings, whose order she alone knew. Among other things, she would show me some geographical maps that she had made herself in a drawing notebook.

These later inspired me to make beautiful maps of countries in geography class. She showed me a map of Southern Albania with the prefecture of Gjirokastra, the Ionian coast, and Chameria. “Here, this is Chameria, my son! And here is Corfu opposite! Even Corfu was ours!”

When I grew up later, when – as Sejfulla Malëshova says – “I came to my senses,” that is, I became aware, I didn’t even discuss that the issue of Chameria and Kosovo was as my mother had told me, but this thing about Corfu, I don’t know why I looked at it with suspicion. Of course, the whole mainland was Cham, Albanian, as were the two small islands below Corfu, Paxos and Antipaxos, but the islands was Greek.

I often asked myself: how is it possible that the coastline from Cape Stillos, where Albania ended, to Preveza and Arta, where Chameria lay, was Albanian, while the islands were Greek. Later I became clear by reading and seeing that there were Albanians not only up to Arta but also further down the coast and on the mainland, and also on the Morea (Peloponnese) peninsula, only they were called by another name: Arvanites, or Arberors.

Years would pass, and I would read the works of a number of our scholars, whom I would get to know personally, such as Dhimitër Grillo, Koli Xoxi, Irakli Koçollari, Aristidh Kolia, Anton Belushi, or I would have direct contact with, like Jorgo Jeru, etc.

I don’t want to talk about the relationships I had or have with each of them, because that would take a long time, but for me today everything is clear, including what is called the island of Corfu, or as the Greeks call it: “Kerkyra.” The word we are talking about is Chameria. My mother talked to me about it constantly even when I grew up later…!

Let’s move on. In the fourth grade of elementary school, I had a teacher named Merina Frashëri (Arrëza). She impressed me because she stood out from the other teachers at the “Papa Llambro Ballamaçi” elementary school that I attended. There was something special about her appearance, her dress, her behavior, and her words that distinguished her from the others. My teacher Merina, I say today from the height of years, was distinguished by her nobility. She was a rare woman.

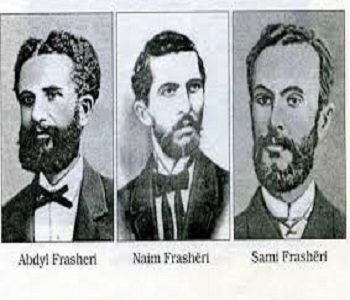

Being a good student, she kept me close and we often had conversations outside of class. In one of them, she whispered to me: “I am from the Great Frashëri family. My grandfather was named Mehmet Frashëri, and he died in Albania. There weren’t three Frashëris but four, and more, and their brother is also Mehmet, my grandfather, who was the youngest of the Frashëri brothers, after Sami Bey. But he is not mentioned anywhere, even though he is a patriot like them and strived for Albania.”

These statements of hers made a great impression on me and were deeply imprinted in my memory. Later I would understand that the class struggle took its toll and, if they themselves had lived, the Great Frashëri family or their descendants in Albania, it is not known what their fate would have been as “bourgeois,” or even worse as “feudals” and “landowners.”

My honored teacher Merina also took me to her house and there I met her husband, the distinguished Korça poet, Skënder Arrëza, who excelled in his early days in the 1930s of the 20th century, and contributed as a creator in the subsequent years in the city of Korça. Only he did not have a long life. He was a friend of Kristaq Cepas, also a poet of the 1930s.

At the same time, they were distinguished and dedicated educators in the city of Korça, in its gymnasiums, for the subject of literature. The biggest impression was left on me by “madam” Merina, as we respectfully called our teacher in our time, especially in elementary school, with what she told me about her Mehmet Frashëri, perhaps after we had done Naim in the fourth-grade reading book.

Even today, I remember the noble, my teacher Merina, and she reminds me that we owe a great debt to the Renaissance and the Frashëri family, until the figure of Mehmet Frashëri is brought to light, who did so much for Albania and the Albanians and saw with his own eyes the massacre that was done to Albania in London and Paris, until he closed his eyes in 1919, leaving Kosovo and Chameria outside of it.

Thank goodness Abdyl, Naim, and Sami did not live to see the Albanian tragedy, the Albania that was “slaughtered like lambs” in Berlin (1881), London (1912), and Paris (1918-1919), in favor of the insatiable neighbors. In the fifth grade and above, I had very good teachers. I want to single out two of them, the geography teacher Alqi Krastafillaku, who is no longer living, a teacher dedicated to her subject, and Mrs. Pandora Xega, the director of the 7-year school, who taught us history.

When we started with her, she gave us a piece of advice: “Whoever wants to, you students can buy the history of Albania for the seventh grade and learn the history lessons from there.” I remember we were doing the “Albanian Pashaliks,” that of the South, the Pashalik of Ioannina. She called on me to answer a question. I had learned very well, history was my passion, and I spoke about the state of Ali Pasha Tepelena.

Among other things, one thing sticks in my mind. Ali Pasha, unlike the states of the East, created in his state a police force according to the model of Western states, unparalleled in the Ottoman Empire. So, this oriental Pasha was walking in the footsteps of the West and for 35 years he led an entire state, whose capital was the Albanian Ioannina, the main city of Chameria, Epirus.

Two things remained in my memory: that Ali Pasha Tepelena was a second Skanderbeg, and the flourishing of Chameria at that time, as a political unit. I want to thank my history teacher, Pandora Xega, who explained the history of Albania with such passion and who opened our horizons as students, by working with the texts of higher grades. Ali and Chameria would again remain two inseparable synonyms from that time, when nothing was stirring about them.

I was not more than 11-12 years old. It was around 1962. At this time we had a very major event, the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Independence. My father was subscribed to the newspaper of the time and I, besides my lessons, found time and read it. I was even a regular member of the city library and I read the newspapers that came there. In 1962, two or three articles about Hasan Tahsini also came out. What has stuck in my memory is the one by the orientalist Jonuz Tafilaj, which was also the longest, almost a page of the newspaper.

This was my first contact with Hoxha Tahsini, alongside other Rilindas. At that time I also read articles about other Rilindas, especially about Ismail Qemali. I still keep from that time newspapers with jubilee writings about independence and the Renaissance, about the prominent figures who laid the foundations of the nation, such as Ismail Qemali, the Frashëri family, Pashko Vasa, the Dinos of Chameria, etc., etc.

For me, the purchase of a radio at home was a great event. It must have been 1963 or 1964. Since then, in addition to the books I bought or read in the library, I listened to the radio. I wanted to know as much as possible about Albania and the Albanians. History attracted me like a magnet. I read various monographs on prominent patriotic figures. Living in Korça, I tuned in to the stations of neighboring countries where Albanians from ethnic lands lived.

I didn’t know a single word of Greek, but I listened to the stations of the neighboring Greek cities, like Florina, Thessaloniki, maybe others, regularly, mostly for the songs; “ellenika tragoudia,” Greek folk songs. Among them, I remember one that mentioned Albanians, such as: “Kapedanios Arvaniti / Karrocieri fukara” (“Captain Arvanite / Poor coachman”), or something like that…! Their folk melody and as much as I could guess from the words, attracted me and I thought about the Albanians of Greece, about Chameria, etc.

But this was a daily occurrence. I would catch Ohrid in the Macedonian language. But there was also half an hour of Albanian folk songs, played by the Sazes of Ohrid. These were like medicine for me. The Albanian element was alive there. This was important to me. When it was 2:30-3:00 PM, every day I listened to Pristina.

There was a show with “Greetings and wishes from our listeners,” which played songs in Albanian (mostly), then in Serbo-Croatian and Turkish. I still remember when it said the title of the show in Serbian: “Pozdravi i cestitke, na nasoj slusajatsa.”

I listened to these stations daily for years, trying to learn as much as possible about the Albanians of Kosovo, Macedonia, and Chameria. Everything was registered in my memory, especially the names of the cities and villages of Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, where Albanians lived, or from where they greeted in emigration. My memory was like that dry land thirsty for water, to learn as much as possible about the Albanians…!

There were some subjects that I loved, such as history, literature, geography, and when I entered high school, also philosophy. We had very good professors at the “Themistokli Gërmenji” high school that I finished, to whom I owe a lot for my formation.

I cannot fail to mention their names such as: in literature, professors Dhorkë Qafeci, Loreta Xexo, etc.; in history, the director of the high school, Ilia Treska, a very prepared person; in geography, the passionate Gaqo Opingari; in elementary knowledge of Marxism-Leninism (philosophy), Mr. Franklin Xega, etc. etc. To these and others, I express my gratitude.

My former passion that I inherited for literature gradually shifted towards philosophy and history, even though I continued to create poetry and write beautiful compositions, which my literature teachers read in the classes where they taught, as good compositions. I remember one of them about the work of Gavril Dara: “Bala’s Last Song,” which I wrote entirely in poetry. It was my interest in the Arbëreshë of Italy.

I remember now as I write these lines, two stanzas that have stuck in my mind: “Gavril Dara sits / On a seashore,/ Time has not erased/ The distant memory./ This Gavril sits / In Calabria / And casts his gaze / Towards Arberia…!”

I want to say that my interest in the Albanians had conquered my being and, in one way or another, it was also expressed in my life. I was interested in Kosovars, Macedonians, Chams, Arvanites, Arbëreshë, the entire diaspora. I read wherever I could about them. I remember that I deliberately read books that talked about Albanian partisans who had participated in the liberation of the lands of Yugoslavia, in order to learn as much as possible about the Albanians in Yugoslavia.

Meanwhile, you found almost nothing about Chameria. Nevertheless, this pushed me to search more and always search in the works of the Rilindas, even though a careful hand of censorship did not publish them, or shortened the parts that talked about Kosovo and Chameria. For Kosovo, under the prism of the war with Yugoslav revisionists, large articles, often “sheets” that took up a page of the newspaper, came out from time to time in the main newspaper of that time, “Zëri i Popullit.”

In a sense, these were very informative for me who was interested in the ethnic lands. I tried by all means to complete my patriotic formation, especially for Kosovo and Chameria. Such a field was the Renaissance, so from the years of high school, I focused on it. Here a large part is literature, where we studied figures such as Naim Frashëri, Sami Frashëri, Pashko Vasa, Kostandin Kristoforidhi, and others.

I can’t forget at that time, the 60s or 70s, I heard Radio Vatican’s Albanian broadcast talk about Chameria in detail, at a time when in Albania “not a fly stirred,” it was called “heresy” just to mention the name. I read books that talked about saboteurs and indirectly learned about Chameria, Kosovo, etc. I was like a magnet that attracted everything, just to learn as much as possible about them.

Things changed a lot when I went to university in 1969. I want to express my gratitude to the employees of the libraries, both the National one and those of the University, the Academy, the Faculty of Philology, and in a special way the Library of the Institute of History, where for years and years, I read literature that was “allowed,” and the reserved one, with and without verification.

They, with their simplicity and kindness, did not spare themselves and helped me read those that were “forbidden,” such as the newspaper “Rilindja” of Kosovo, etc. etc. Thus from the branch of Philosophy that I completed for 4 years and this “crazy” passion I had for the Albanians of ethnic lands, my topic on Hasan Tahsini emerged. Behind Hasan was Chameria.

I did not want to spend my time dealing with genuine philosophers, such as Hegel, Kant, Sartre, etc. The whole world was studying these. I needed Albanian philosophers, the ideologues of the Albanian National Renaissance. And one of them, who naturally became ingrained in my memory, was the Rilindas Hoxha Tahsini.

Looking at Kristo Frashëri’s album: “Albanian National Renaissance,” with the corresponding photographs and explanations, my attention was drawn to the figure, the appearance of Hoxha Hasan Tahsini, with that turban on his head, which was nothing but an expression of a knowledgeable person in the circumstances in which he lived in the Ottoman Empire.

For me, he represented the Albanian philosopher, the scientist, the ardent patriot, the distinguished educator, the pure Rilindas, the political activist, the great organizer, the person dedicated to the extreme to his people, national liberation and social progress throughout the Ottoman Empire.

Aware of who I was dealing with, I insisted on taking this figure as a dissertation topic and, despite the obstacles they put in my way, I achieved my goal. Now and in state channels for my qualification, I worked to bring to light a Rilindas, to bring out Chameria.

Determined on my path, I walked without ever stopping, regardless of the difficulties. I was also helped by the fact that in the third year, the subject of “Albanian political and social thought” was introduced by Professor Zija Xholi, which dealt with the worldview of our Rilindas.

I had read so much about the Renaissance and the Rilindas in high school and university, so much so that just by listening to my professor, I would absorb his words, and it is the only subject where, during four years of studying Philosophy, I did not open a single page of the lectures or another book to read. In this subject I went “unprepared” and got the maximum evaluation…! The existence of this subject in the program of the Philosophy branch helped me to take a topic like the one I took, for “The life, work, and ideas of Hasan Tahsini.”

Before I conclude these notes on my acquaintance with Chameria and Hasan Tahsini, I want to say a few words about the positive role played by the arrival of professors from the University of Pristina at our university to hold lectures. The lectures they held, especially in the Faculty of Political and Legal Sciences, where I studied, and in the Faculty of Philology, were a real school for me.

And how can I forget the lectures of the orientalist Prof. Hasan Kaleshi, of Prof. Ali Hadri, of Prof. Syrja Popovci, of the first rector of the University of Pristina, Prof. Dervish Rozhaja, and dozens of others that we listened to in the golden decade (or ‘decenia’, as the Kosovars themselves said) of the 1970s of the 20th century.

I cannot fail to point out a couple of moments related to the problem in question. I was listening to Professor Kaleshi in the large hall of our faculty. I was a student then and I didn’t hesitate, when I found it reasonable, to ask “spicy questions.” I remember that in one lecture, while talking about the League of Prizren, with documents, he expressed his dissatisfaction with how the figure of the Rilindas Abedin Dino was treated in the history of Albania.

“He was,” the professor emphasized, “the head of the Albanian League of Prizren for the South and he was an ardent patriot just like that. Even when he was the Foreign Minister of the Ottoman state, that is, at the apogee of his state career, he declared that he was ready at any moment to abandon the high position he held and come to fight as a simple soldier of that League.”

And time proved Prof. Hasan Kaleshi right about Abedin Dino. I remember in another lecture, where he was talking about oriental influences on the Albanian language, he mentioned the word “çifteli” (an Albanian musical instrument from Northern Albania) as an influence from Turkish, as çift-teli (meaning an instrument with two strings, as it truly is).

Both words are Turkish. In that lecture, I noticed that the reaction of the hall was not positive, and neither was mine. But the professor was right. The word came from Turkish, even though the instrument is authentically Albanian. / Memorie.al

Continued in the next issue