By Shkëlqim Abazi

Part Eleven

Memorie.al / I were born on 23.12.1951, in a black month, of a time of sorrow, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief investigator, Llambi Gegeni, the ignorant investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the cruel prosecutor, Thoma Tutulani, mutilated me at the Internal Affairs Branch in Shkodër. They split my head, blinded one of my eyes, and deafened one of my ears, after breaking several of my ribs, half of my molars, and the thumb of my left hand. On October 23, 1968, they took me to court, where the wretch Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After having half of my sentence cut because I was still a minor, sixteen years old, on November 23, 1968, they took me to the political camp of Reps and from there, on September 23, 1970, to the Spaç camp, where on May 23, 1973, during the revolt of political prisoners, four martyrs were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad: Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a perfectly normal process in the democracy we pretend to have. But on October 23, 2013, the General Director of the “Renaissance” government sent Order No. 2203, dated 23.10.2013, for the release of a police employee from duty. So Divine Providence intertwined with the neo-communist Renaissance Providence and, precisely on the 23rd, I was replaced by none other than the former Sigurimi operative of the Burrel Prison. Could anything be more significant than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by the former persecutor!

Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

R E P S I

(Forced Labor Camp)

Memoir

Six Hundred Grams

(The routine of a day at the dormitory camp)

On May 5th, Martyrs’ Day, or the day of blood spilled traitorously, was a holiday, so I didn’t expect any new developments. After I stuffed myself with food, I lay carelessly on the bed. Even before I fell asleep, I heard a commotion in the corridor. But I didn’t think about it; noises were more than common in that environment.

Then I heard the door of my cell open, and three police officers entered furiously. But I still didn’t lose my cool: “They must have the wrong address,” I thought. However, the dilemma didn’t last because two of them grabbed me by my arms and legs and hurled me into the corridor.

Whenever I thought about the final confrontation with the investigators I had deceived, I never imagined it would happen like this. I envisioned myself handcuffed, hands and feet in irons, on the second floor, in Baldy’s office.

I imagined Baldy himself, enraged by the disappointment of not fulfilling his dream of being transferred to Tirana, disfigured by anger, taking off his slippers and using a rubber stick, hitting the soles of my feet until they were numb. Then, when he got tired, Spiro would take his turn and…!

But here, my imagination got stuck. I was unable to predict what would happen next when it was the redhead’s turn. So, in my head, I had decided that at the right moment, I would pretend to be unconscious, although I didn’t know how well that would work, and with that, I would pay the price for my two weeks of convalescence.

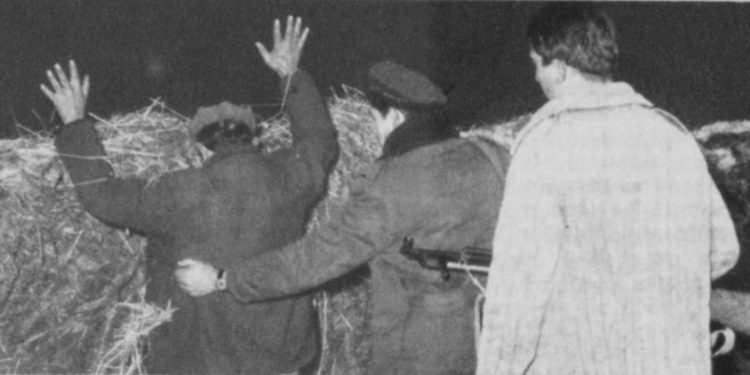

But when I found myself in the middle of the corridor, between three big-bodied ignoramuses, each one stronger than the last, which were hitting and hitting without mercy with all their might; with fists, with kicks, with sticks; I lost my mind.

The blows came in a flurry, as soon as I moved to one side; they would throw me to the other, where the same thing awaited me. They turned me into some kind of punching bag; I didn’t know which part of me to protect first.

I started to howl with all my might, the echo reverberated down the corridor, while dozens of others started screaming and shouting louder than me. There came a moment when it was unclear who was howling more, me, who was getting beaten, or them, who were screaming pointlessly to attract the attention of the executioners to save me.

Since they were feeling cramped in the corridor, they dragged me outside into the middle of the yard, to get their fill of beating. Now, from three, they became six. Each one was hitting on his own accord. There they were freer and they beat me up thoroughly. At some point, I collapsed to the ground, unconscious.

I don’t know how long it went on, but when I came to, I couldn’t open my eyes. It seems they had swollen badly from the punches, so my eyelids were shut. However, my ears were pricked. I distinguished a deep voice rising above the others:

“You’ve completely ruined him! Now, what are we going to do? The Chairman wants an answer! He wants him alive! Why, should I lose my job over an enemy?!”

This voice came to me clearly, but I pretended to be unconscious.

“We’ll tell him he tried to escape from the bathroom when we took him out for personal needs,” a second voice intervened.

“Man, let’s put a bullet in him, fill out a report and goodbye, we’ll close this issue! It’s not like he’s the first one!” another one added.

“Look, look, man, this Zala guy is right! These rotten traitors deserve a bullet! In the end, it’s one enemy less! This way we get rid of the trouble, and the Party is saved! Come on, he’s dead anyway!”

These words pierced my brain, as if they had driven a nail right into the top of my head. I gathered what little strength I had left and moved my limbs.

“The doctor, quick!” I heard the voice of the one who had spoken first again. I ended up in a hospital room, my brother! I spent seven days lying down, with serum and needles, but without a beating. After that, they changed my investigators.

I don’t know where Baldy and the Redhead ended up, but I guess it wasn’t in Tirana. I didn’t have a similar story with the new one. In fact, he didn’t ask me anything, and even when I happened to tell him some truth, he didn’t write it down.

“You are a dangerous deceiver,” he told me. “You filled twenty full files for us, with bureau secretaries and dead people, from the time of the Germans!”

Practically, my investigation was closed! They gave me a formal trial, gave me a twelve-year sentence, and here we are together, here!” P.L., the prisoner from Vlora, finished!

The second story, very different from the first, but just as painful and heroic. In early autumn of 1970, when they transferred me from Reps to the Spaç mines, for a while I had as my bunkmate, or sleeping neighbor, the man from Kukës, Avzi Nela.

He was a man in his thirties, dark-skinned with very expressive eyes, a man of few words, and authoritative. He spent almost all his free time reading, but he also wrote poetry in a notebook with a ruled margin, in tiny, clear, and legible letters, perfect cursive.

The first few days we only exchanged courtesy greetings, because he seemed like a closed person and didn’t really like unnecessary talk. So I didn’t bother him because I, too, was busy with my French.

As the days passed, we started to exchange some books and thoughts about them. One day, tired from the night shift, I had fallen asleep uncovered on the bed. He had thrown one of his blankets over me. When I woke up, I recognized the blanket, but I didn’t see my neighbor.

I got up, folded the blanket, and went out. As I was going down to the bathroom, under the shade of the acacia tree, I spotted my neighbor with a book in his hand. As soon as he saw me, he invited me to sit next to him:

“Lunch hasn’t been served yet, why are you up so early?!”

“I woke up, and I thought it was better outside than inside, it’s unbearable.”

“Don’t lie down uncovered! The heat won’t hurt you, but be careful of the cold, my friend. We’re in prison and there’s no one to take care of you!” he said to me, with the meticulousness that characterized him.

“Oh, Avzi, I’ve noticed often, when you give advice or explain something, you take on the posture of a teacher. I haven’t asked you, what work did you do?” I asked him jokingly.

He laughed wholeheartedly; his eyes sparkled with a childlike shine, a special light emanated from the depths of the retina of those eyes, which I have not seen anywhere else.

When he stopped laughing, he put the book aside and turned to me: “Yes, you hit the nail on the head! I was a teacher! It seems this habit has stayed with me since the time I taught in the villages of Mat.”

“What? I thought you were from Kukës?” I interrupted him.

“I am from Kukës, but I was a teacher in Mat.”

“Where?”

“Here and there, in the villages.”

“From the city of Kukës…?”

“No. No, I am not a city dweller, but a villager and the son of a villager, born and raised in the countryside.”

“And did you finish school in the village?”

“No, I finished high school in Shkodër. Then they assigned me to the villages of Mat.”

“So, you know this kind of life well?”

“Yes, indeed! Except for the years of high school, I spent the rest of my life in the villages, among the highlanders.”

“How was life?”

“Black and blacker! The highlander has always had a difficult life, in fact, I can say that he has always been on the verge of survival, but now he is completely destroyed. That simple, uneducated peasant, who was full of loyalty and manhood, is now reduced to a serf and a flatterer of the cooperative chairman and the foreman.

The Migjenian misery, inherited in the northern areas, was made even worse by the premature collectivization. I grew up in the village, I ate from the same bowl with the villager, I shared the good and the bad, but what happened after collectivization was unimaginable even for Migjeni’s imagination. The heroic and noble peasant in his poverty was turned into a slave and a beggar for a bite to eat.”

“Of course, this misfortune has spread nationwide,” I interrupted him.

“Maybe you’re right, but this character deformation is more obvious in the north, since ignorance and poverty also prevail in those areas.”

“Maybe,” I confirmed.

“I was discussing this character distortion with some trusted friends and companions. But these conversations reached the ears of the Sigurimi people and the party cadres in the village. Of course, communists don’t like criticism; they are afraid of free thought.

Finally, when I realized that the State Security was surveilling me, I was forced to escape to Yugoslavia, along with my wife, to escape persecution.”

“When was this?”

“It’s been a little while. We left with a broken heart, because we were leaving our homeland behind.”

“But why did you come back?”

“I didn’t come back on my own. The Sigurimi and the U.D.B. have a secret agreement to return Albanian political fugitives to their respective countries, whether they are from this side or the other side of the border. Now my whole family is in prison.”

“I’m sorry!” I tried to comfort him.

“No, don’t be, man, I’m not the only one! In fact, I don’t regret anything for myself, after all, this is where men belong, but I feel sorry for my wife and the rest of my family members, who are suffering from internment and persecution.”

“I feel sorry for them!” I repeated.

This is what Avzi told me as the reason for his escape and his subsequent sentence.

I had been in Spaç for some time. With the reorganization into brigades, they separated us into different barracks, but we kept our friendship for a long time. Whenever we could, we would meet, exchange a book, and read poetry in circles of friends. When literature was discussed, as the youngest, I listened carefully to the arguments of the more knowledgeable, especially Avzi. He reasoned logically. He was generally silent, but when he debated, he was convincing; he illustrated his thoughts with concrete examples and similar comparisons.

He knew the northern poets in detail, especially Fishta, but also others from both sides of the state border. He insisted, sometimes to the point of stubbornness, on the all-inclusive thesis in Albanian literature. But, to preserve the naturalness and regional identity, according to him, it is necessary to write in both dialects:

“We have examples in the field; you just need to sit down with ordinary people, and you’ll immediately understand that the people are the most reliable source of national folklore and philosophy. Intellectuals have the duty to collect it, to process it carefully, but they have no right to deform and muddy the source. Poets are the owners of ideas, but not possessors of their creations.

The moment they publish them on paper, they become a nationwide food. But food is only eaten if it tastes good; otherwise, it is not absorbed, and if you eat it by force, you will vomit it! This is poetry; it is written for the people, in their language and taste. Whoever violates this norm is destined to be abandoned and forgotten!”

He gave Fishta as an example:

“His bones were thrown into the Drin, but his work is sung by rhapsodes all over the Highlands!”

Then he insisted:

“We will be ruined, or rather, whoever survives and sees it will realize that in the end, all these Slavicisms, which are well known to be a political transplant in the trunk of our culture, will be eliminated by time and the national language will retake its rightful place!” he added with unwavering conviction in his ideas and expressed himself openly among intellectuals.

He polemicized with the alternative view that was supported there by intellectuals trained in Eastern schools, led by the pro-Soviets.

The language between them became so sharp that sometimes they would turn their backs on each other. But the anger didn’t last; they would quickly return to the half-finished topic, but each one fanatically defended his own dogma and they would part again, with the same arguments, just as they had started. Now after so many years, when I recall Avzi’s thoughts, I ask myself:

“Was he right or not?”

The answer:

“Yes! You were partially right, my good friend! But even today, after forty years since our fierce debates and twenty-three years since your tragic end, unfortunately, this linguistic mishmash still continues.”

But, let’s go back to the story: One autumn day, some visitors came for a meeting. As was customary in such cases, a meal was set up with the closest friends, that is: with those with whom the conversation was salty. To help the destitute who had no family aid, “Sadaka” (charity) was practiced, but this was done with tact, without insulting them. Because this category was indeed poor, but dignified; they did not accept alms and refused invitations.

The most typical was Avzi; he had no help, but I never heard him complain once! He rejected fabricated invitations with contempt. To be accepted by him was considered a special honor, reserved for the inviter. Because, as a rule, he even refused his own compatriots. So, with my friends, we organized a lunch that day. We put Avzi at the head of the table, as the guest of honor, because we considered him distant, from Kukës.

When that lunch ended, with the little that my family members had been able to bring me, the friends left for their barracks. Three of us remained, Avzi, Tomor Allajbeu, a compatriot of mine who would have a very tragic end, about whom I will speak when it’s his turn, and me. We talked and talked about different topics, until the conversation came to the sublime sacrifices that prisoners had to face to survive daily hunger in prisons without giving up.

At that moment, Avzi took the floor: “Men, it is terrifyingly unimaginable what can happen to a human personality in conditions of extreme hunger. Not only in prison; a whole people has now been turned into laborers, condemned to live in daily hunger, in conditions of endless misery, where ninety-nine percent of the population is experiencing a food crisis.

While the free world no longer talks about food security for the population, but strives to discipline its uncontrolled use, which means, to orient the consumer towards quality products and healthy assortments. With us, they can’t even fill their bellies with dry corn bread!

Now, in the second half of the twentieth century, you still see hungry children. In the school desks in villages, and even cities, you find skinny children, as in the distant and forgotten middle Ages. Through hunger, communism managed to subdue, depersonalize, and enslave all the peoples of the East. But with us, the vileness has reached its peak. In addition to the above, they corrupted morals, robbed character, even from the noblest families.

Hunger equates the slave with the animal. The brain of the hungry person loses the primary function for which God created it, rational thinking, and becomes obsessed with animal instincts. An empty stomach turns a person into a deceitful being. In interrogations, the Sigurimi agents have successfully practiced this destructive evil on souls. Through hunger, they have filled pages and pages of reports with false depositions for criminal acts never committed. They have denatured the characters of honorable men and respectable women.

They have forced people to admit to things they didn’t do, to lose their dignity and even their honor. I will tell you what happened to me: ‘For almost two months in a row, the investigator asked me to confess to conversations I had never had with other people, my colleagues, or strangers. Of course, it was not about the act I had committed, because that was a done fact, but they wanted to enlarge the group. In the end, this was their duty, to force me to testify with my signature about imaginary people with whom I had supposedly collaborated. But it was not in my nature to admit things that were not done and that were not true.

After many pressures and physical abuses, when they saw that they were not achieving what they were aiming for, they changed tactics; they put into action the method of “softening.” It was the first time I heard the term “softening” in a human context. I had heard of taming animals, but it had never occurred to me that a being with reason could be tamed.

They called the method that because it was successful for taming wild and dangerous animals, who, through hunger, managed to subdue even leopards and tigers, so much so that they turned them into circus actors. When the investigator threatened me with “softening,” I met it with a contemptuous smirk, but very soon I would see the trouble: ‘Mr. Investigator, I hope you will be the one to soften! During my years of work, my leaders and colleagues accused me of sentimentality. I believe you have noticed how many times you have insulted me and I have endured it with composure.’

‘We’ll see now how composed you will be! Get it straight once and for all, that you can’t make fun of us, sir!’ he waited, but I didn’t answer, and he continued: ‘It would be more reasonable for you to bring them out yourself with understanding. We know who you have spoken with, who you have acted with, but we wanted to hear it from your mouth.

Why, are we just anyone, the eye and ear of the party?! I told you from the beginning; go straight, so you can have it easy! But you didn’t want to cooperate; you chose the path of opposition. Let’s see now how long you will last!’ After this lecture, which, to be honest, I had heard for the umpteenth time, he went out, leaving me alone, maybe with the goal of making me think. Memorie.al