By Gjin Musa

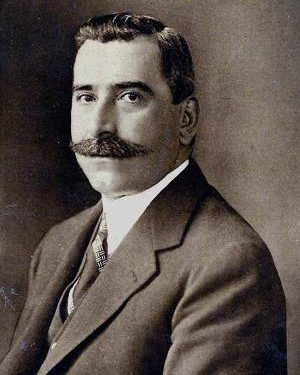

Memorie.al / The preparation of specialists in various fields of knowledge, art, culture, etc., for specific problems, are a need, a benefit and, at the same time, a lack that requires us to think. In the encyclopedia of Albanian culture, the word “Mjeda” has found its specialist, the researcher Mentor Quku, who for thirty years in a row, among archives and libraries, among seminars and lecture halls, among social environments and special people, inside and outside the country, has sought, discovered, researched and collected the knowledge and knowledge about Mjeda and, like a powerful calamity, has absorbed this knowledge, like a diligent bee has processed their nourishing pollen, and like a healthy plant has tied the fruit, the fruit of thirty years of toil, sweat, sacrifice and has given us his work “Mjeda” in 7 volumes, presenting us with Mjeda as a man of character, as a formed lyric poet, as a multidimensional scholar.

So, as a pinnacle of art and as a profound scholar. But, as Shantoja says: “Great horizons are not grasped with a glance”, our Mentor has also given us seven volumes of Mjeda; I emphasize: one Mjeda in seven volumes, dispelling the black clouds of unrealistic socialism, clearing the smoke of misinterpretations and malignant approvals, to enlighten us about this personality of Albanian culture.

Mjeda 1 (1866-1888) Youth.

Mjeda 2 (1888-1889) Albanologist.

Mjeda 3 (1899-1912) Homeland

Mjeda 4 (1912-1925) Politician

Mjeda 5 (1925-1937) Old Age

Mjeda 6 Bibliography

Mjeda 7 Contemporaries.

(It presents Mjeda in the memories of contemporaries. For the original idea, it is a first work of its kind in Albanian literature). In three other volumes (8-10), the author will summarize the complete creativity of Mjeda. So, a comprehensive and meticulously documented work: he has not forgotten any writing or indication that could be useful for knowing or understanding Mjeda. The author awakens the desire, especially in this time of corrections, to know Mjeda better, since the work has no class analysis, no partisan anger, and no spirit of prejudice.

There is sometimes enthusiasm, but not indoctrination; there are sometimes equivocations and repetitions, but not speculation. Thus, the work with its rich and diverse material, with written and oral sources, with new events and episodes, with documents, facts and memories, with diaries, interviews and letters, results as a volume that offers us an important contribution, full of cognitive and educational value. And we need these works, to build new foundations in our national culture, for a new intellectual formation, more objective, more just, more scientific.

To study Mjeda, we have, mainly, two monographs: and, as official studies, the History of Albanian Literature and the Albanian Encyclopedic Dictionary, typical politicized monographs and studies that, despite having good data and analysis, contain socialist lies: inaccurate and erroneous statements, misunderstandings and tendentious and speculative distortions, written without much education that create a dent in the conscience of socialist letters. After these studies, seen from a new perspective and critical evaluation, the work we are reviewing appears richer in factual and informative material, sometimes also analytical and interpretative, more complete, more loyal, more pure, because it was written, as Kuteli would say, “without violence and rape”, but with sense and makes sense.

Thus, his life as a student and his activity before returning to his homeland, has been illuminated with new data; some misinterpreted comments by socialist criticism have been illuminated and closer to the truth, and not, as Marxist-Leninist criticism expresses it, that “the Jesuit environment is a prison and the life that takes place there is a repressed, unbearable, oppressive, enslaving, exhausting life”.

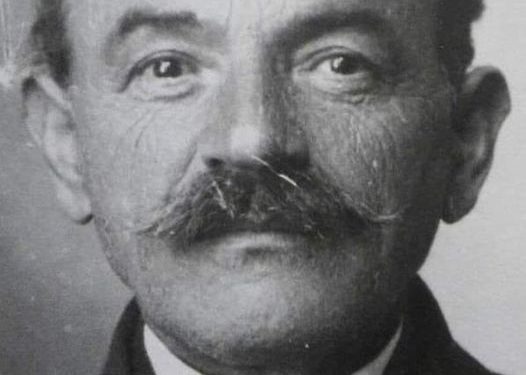

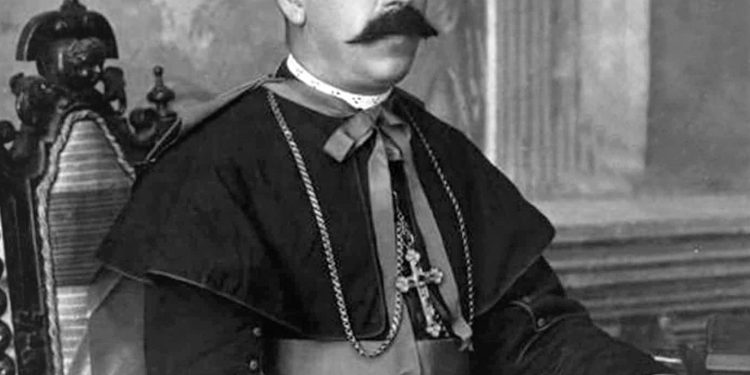

In the work of Mentor we get to know and enjoy the true portrait of Mjeda: a good priest, ardent patriot, a valuable linguist, an outstanding scholar. The relations Mjeda-Jesuits, Doçi-Mjeda, Mjeda-Fishtë, are presented in a new focus: without socialist slander, without baseless rumors and without deliberate misinterpretations, but more directly, more clearly, more documented. So, a Mjeda not attacked “by an entire clerical current, the roots of which must be seen in the Vatican”, or as Enver Hoxha said: “disgusted, condemned and persecuted by the Vatican and its agents”.

After Mjeda, the author becomes enthusiastic and writes: “Mjeda created the societies ‘Agimi’, ‘Bogdan’, ‘Shën Jeronimi’”. In fact, the “Agimi” and “Shën Jeronimi” societies were founded by Monsignor Mjeda, who is known to have opened schools, founded societies, brought printing to Shkodra, created the political group “Ora e maleve”, studied and published about the canon and wrote religious poetry, published newspapers and magazines, helped various authors with publications, organized performances. In other words, he developed rich and diverse social activities. While the “Bogdani” society was founded by a young group with the Jesuit Father Gjenovic. In my archive I keep the file of the documents of this society (after all, my father was among the main founders).

“Bogdani” was founded on 23.11.1919 in the presence of Father Gjenovic, who donated several books for the library and the first edition of the work of Monsignor Bogdani, while in the list of members of the society that I keep, Dom Ndre Mjeda is registered as an honorary member, on 30.11.1923 and in the summary statement of accounts, it is noted that he donated 20 florins to the society. “He rarely came to meetings and, even more rarely, he discussed,” my father used to tell me. “Fishta, on the other hand. He collaborated with our society.”

Historians, historians of education and writers, as our author also claims, have written that the Iballa School was opened by Ndre Mjeda, in fact, with all the contribution he made, that school was opened by Monsignor Lazër Mjeda with patronage subsidies. Even for the Prizren School, they write that it was opened by Mati Logoreci, in fact, it was opened, or rather reopened, by Monsignor Logoreci, while Matia was the (first) teacher. Since the work is still in progress, we cannot express ourselves, but I am making a clarification.

The author writes: “…about the Jesuit seminaries, Mjeda is aware of the perfect education he receives there”. And, below: “Mjeda experienced exile as a result of his desire to be educated in the Society of Jesuits”. He clarified: Not “to be educated”, but for his inner priestly calling and, then, for his priestly mission, which he actually continued until his death. Otherwise, it would be a lie on Mjeda’s part, hypocrisy.

The author himself affirms a truth below: “Mjeda was a convinced religious and a determined cleric”. What does it mean: Mjeda had an inner calling and was fulfilling his priestly mission? And, as Gazulli writes: “why did he exchange (for work) the Jesuit robe for the priest’s veladon. But he kept the priest’s veladon with honor”. Even Mjeda’s movements as a student from one place to another, for objective Jesuit reasons, are not good from the author; “as forced movements of Jesuit seminars” and, not as one biographer writes: “to make him cosmopolitan, cynical and selfish, that is, a worthy Jesuit”, nor as one of my professors told me; “for indiscipline reasons”.

The author has studied Mjeda’s contribution to the alphabet well, but he will return to it when he writes about the Manastir Congress. I have given an opinion unknown to Fishta, publishing for the first time the fragment from the interview given to Gjiro: “…the need was felt to arrive at the conclusion of a single alphabet for everyone and to eliminate in a consistent manner all the list of these alphabets, which for so many years had created a series of reasons for internal opposition,… I managed to adapt the Latin alphabet for the entire country… I avoided, of course, the pedantry of grammarians and the elaborations of philologists, in order to approach above all the living source of the spoken language”.

In this saying there is also a truth that also applies to Mjeda, despite the fact that his name is not mentioned. Add, then, the notes we have from P. Pal Dodaj, P. Pashko Bardhi, and the oral memories from P. Justin Rrota and P. Viktor Volaj, to get to the truth about the positions of Fishta and Mjeda, on the issue of the alphabet in the Congress, which we expect Mentori to elaborate (unlike the politicized articles and studies), in the future volumes. And, along with this, also the positive position of the Jesuits (so talked about) on the problem of the alphabet.

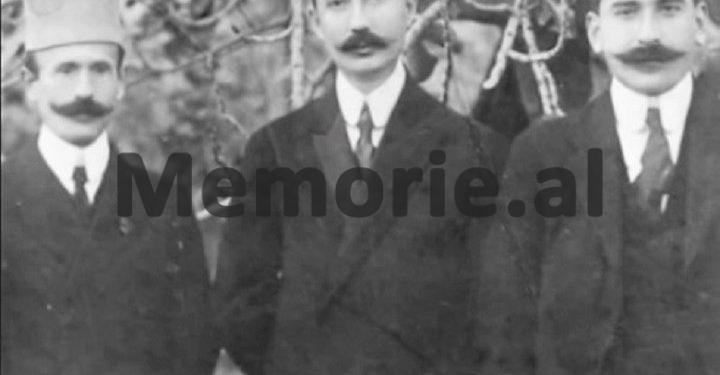

But what we like to emphasize is the unity in changes of these personalities. Suffice it to recall that Fishta, Mjeda, L. Gurakuqi and Logoreci sent a joint telegram (so far left in the shade) to the Jesuits on the decision on the alphabet. Fishta, even, expressed a very good assessment to the Austrian consul for Mjeda and the notes on the divergences, etc. held during the sessions, they left the task to be solved.

About the name of Mjeda’s mother: Luçie?, Domenikë? Luke?

All biographers and article writers who have studied Mjeda have written that Mjeda’s mother was called Luçe. Finally, the media scholar Mentor Quku preferred to call Mjeda’s mother Luçe, but to be on the inside, he has given everything that has been written on this point. Mainly two opinions: Domenika is equivalent to the names Dilë, Diellë, Luçe, Luçie, Luke. And Mjeda’s mother… had two names: Domenika, Diella, Dile and Luçie, Luçe, Luke. For accuracy, he has also written that the baptismal register of the parish of Shkodra has Domenica.

Our opinion: When our highlanders wanted to give pagan names to their children, the priests, wanting the Catholic to have the name of a patron saint and to remember and celebrate the name, registered it in their registers, with a similar religious name. Thus, for example, Marash, Mirash, Mirak, Mirocë, they brought the name Mark closer to the name. Thus, to the name Luke, they brought the names Luçe, Luçie closer to the pagan name Diëllë, and equated it with the Christian name Domenika, although there is no connection between them, much less a genetic connection. The names Domenika and Luçe are also close, although without any connection. The name Domenika is the translation of the word day and sun.

Let’s conclude: Mjedë’s mother was called Luke. Now, the name Luke comes from the developments Diell, Dilë, Dilicë, Dilore, Diluke and the abbreviation Luke, so: a pagan name, which is not genetically related to either Luçe or Domenikë. The name Luke could also come from the name Çiluke, but not in our case! Without going any further, two more words about the name of Mjeda’s brother: in the work it is written Zuku, as Mjeda has it, which I take as a spelling of the time.

Some linguists consider the name Zuk to be an old, even Illyrian, name and associate it with another name, Zuku Bajrakar. The name of Bishop Mjeda is actually Cuk, which comes from Lazër, Lacë, Lacuk, Cuk. Even some names from the ecclesiastical sphere should be corrected in future publications. In conclusion, we cannot find words to summarize and accurately express the great effort and valuable contribution that the author has made to Mjeda, but let us only say this: this fundamental work will always remain a reference work in environmental studies. Good luck to the mentor, let us enjoy Mjeda. Memorie.al