By Ahmet Bushati

Part forty-two

Memorie.al/ After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

I explained to him on that occasion as much as a policeman could explain in those circumstances, while he, moved as he was listening, followed me attentively. We talked for a few minutes and then we parted. Before leaving the service, he came once more to greet me, hoping that we would meet the next day, which did not happen, because he was no longer assigned to service there, during those last days of my life in that prison. And if I never saw him again, I have remembered him with gratitude throughout my life.

We go to trial and finally I leave the Sigurimi cells

First of all, I am pointing out something that did not impress me at that time. A week before our trial, the Sigurimi, through one of its employees, for many “legalities”, the arrest warrants that are usually issued on the first day of a person’s arrest, were to be handed over to me and my friends after a full year and a half of being in prison!

On the morning of June 24, 1949, in the back yard of the Sigurimi, my friends had been brought from the Gestapo prison, from where we would go to trial together. While the police were tying us up two by two, we spoke cordially to each other, after so long that we had not seen each other. As we left the back gate of the Sigurimi court, heading towards Pogu’s house in the “Badre” neighborhood, where the trial would be held, we walked proudly and responded – as the case may be – with glances or even smiles, to the benevolent glances of some citizens.

As we had not expected, our trial would not be held in public, as it had been for the other groups that had appeared before us, so we could not publicly denounce the tortures that the Sigurimi had inflicted on us. As soon as the session began, a member of the jury, as had been instructed from the beginning, would stand up and speak: “In order to preserve the secrecy of the Sigurimi organ, I propose that the trial be held behind closed doors.”

Since I had finally escaped the torture with my life, the idea that one day in court I would denounce all the tortures that had been inflicted on me, without sparing a single case and not a single investigator’s name, had been my daily consolation. There had been hundreds of formulations that I, day after day, had built in my mind for that case, and this not only to express my deepest anger and hatred for those criminals of the Sigurimi, but also to show the people our souls and the cause for which we were there.

It was truly very unfortunate that such a long detention and filled with so much suffering, would have as its epilogue a pale and formal trial, without people or witnesses, and that would end before it began, as it did not deserve. During the hearing, the tortures that had been inflicted on us at the Sigurim were forcefully denounced, but what good would it do if there was no one to listen to them! To supposedly prove whether torture had really been inflicted on us, they called Ali Xhunga himself to testify, who even on that occasion, with a white face and a big smile, in no more than two minutes, shamelessly denied everything and left, satisfied that the job was done so quickly.

We were the first group to go on trial after that of Pjerin Kçira and again the first group after that of Pjerin Kçira, who were being tried behind closed doors, – so that the people would not learn from the tortures that were inflicted on us and by a military and not a civilian court as before. Our trial would have no criteria or content and would pass under the indifference of that very court, which, as we recently charged with judging our case, seemed only interested in its speedy conclusion, without the need to even think about the punishments that should have been served to them long ago by others. That trial would be mostly characterized by our protests and especially by one of our friends, who, with or without permission, would occasionally explode, venting his anger at the investigators, who had tortured him to stand trial.

If that panel of judges, headed by a military man with the rank of captain – who years earlier had been a student at the Shkodra Gymnasium, in the same class as Ruzhdi Çoba, Qemal Draçini, etc. – would not have been too bothered by our revolting attitude, the prosecutor Namik Qemali, from Vlona and with the rank of major, would not only have shown his hatred towards us by our nervous words, but also by his black face, which would remain serious and full of hatred for us the whole time. Among other things, that communist prosecutor would have asked me: “How did you, Ahmet Bushati, express yourself about Kosovo?” and, when I answered that; “Kosovo was Albanian”, he, as for a “sacrilege” that I had committed on that occasion, would shout loudly and out of anger, would forcefully slam a pencil with a sharp tip, which until then he had been twisting in his hands, on the floor.

So strong and deep would be the indoctrination of the Albanian communists, including one Namik Qemali, who, as tools of denial and destruction of every human and national value that they were, had lost so much of logic, that even though a year had passed since Enver Hoxha had broken with Yugoslavia, they would still continue to call Kosovo “reactionary” and to despise and hate it just like its Serbian friends. Our trial and its decisions, as predetermined as they were, did not need to be prolonged. After another day they brought us back to court and, after lunch, they gave us one plea and one verdict after another. Our respected lawyers like Čeranković, Tedeskini and Shehu, each spoke very few words, since it was clear that nothing mattered.

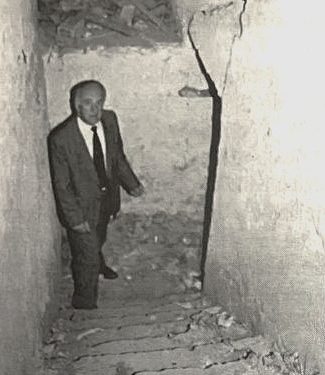

When I left that Sigurimi prison, I was leaving behind a year and a half of solitary confinement and torture, I was leaving behind that unparalleled communist hell, through which hundreds and hundreds of distinguished men and boys of our city had passed before me, for a great tribute that our country had to pay to the communist vampire. When I left behind that prison with dungeons like tombs on the ground, I was also taking with me the saddest impressions. How many men would have had, who had begged for death several times from torture, and unable to find it, one day they would have surrendered to them, signing humiliating trials, with which they, in addition to themselves, would have blamed their innocent comrades and friends, and of course, to spend years with their heads down and their consciences dead.

Meanwhile, there have been many who, for the sake of their honor and good name, have endured torture with dignity until the end, until one day they gave up their lives in the hands of their criminal interrogators. I would have been very impressed if I had heard a man, who, when he could no longer bear the torture that his cruel interrogator was inflicting on him, beg him in a low voice, saying: “Oh, man, stop it!” “Aman, for God’s sake, don’t!”

He left with sorrow for the people of that hellish prison, which seemed to me even more gloomy and miserable than when I was inside it, and since the night had just fallen, and since I had no more days to think about anything, I, along with the convicted former students of the American Fultz, and some others, tied together two by two, finally set off for the New Prison.

PART III

Xhevat Quku with twelve years in prison, Ruzhdi Çoba and Remzi Quku, with ten each, Ernest Perdoda with eight, and Thabit Rusi, Tomë Sheldja, Refik Bushati and I, with seven years in prison each. As we walked, we tried to encourage our people. I remember that I said to a sister: “Be happy that I got out of the Sigurimi alive and, as for the sentences, we are healthy”! Beside us, in addition to the police and our people, there were also some teenagers, among whom were also from my neighborhood, who, with visible concern and revolt on their faces, as well as with gestures, sought to show solidarity with the spiritual state of our family members.

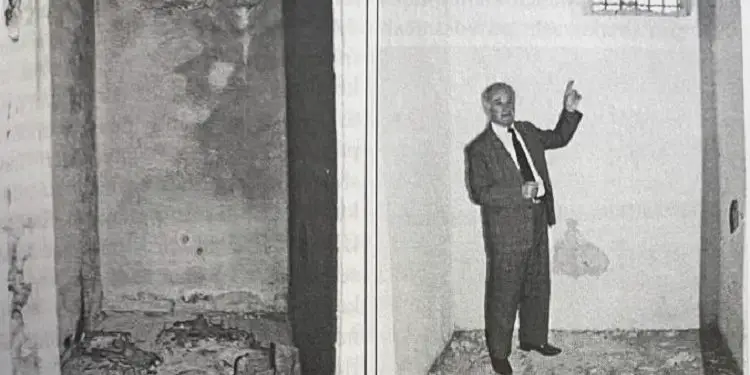

At the top of a hundred meters of the road, shortly after we turned off the “Serreq” – “Perash” road, we entered a small alley and very soon we found ourselves in front of a large, characteristic Shkodra door, behind which we suddenly saw a relatively long, but not wide, courtyard, at the end of which stood a two-story building, which for two years had served as a prison and was called the “New Prison”, which was second in size to the Big Prison. We would soon learn that that building had previously been the home of the Çeka family and some others, who knows for what reason, would also call it the “Suma Prison”, so that prison would be called, depending on the case, sometimes “New Prison”, sometimes “Çeka”, and perhaps even more often, “Suma”!

Behind the entrance gate, there was a corridor about 3 meters wide, inside which a small room was designed for the police officer, using for that purpose the two existing walls of the corridor itself, while the other two sides would consist of two thick iron walls, reaching up to the ceiling. In both iron walls there was a “ladder” for the movement of the police officer, as well as for the possible movements of the political prisoners in the three rooms below.

The prison administration and the ordinary prisoners lived upstairs, on the floor above us. The meetings of the prisoners in the three rooms below – once every fifteen days – would also be held here: the prisoner would stand behind one of the iron walls and, on the other wall opposite, his family members, while the police officer between the two sides would sit on a chair with a small table in front of him. Inside this room that first night, after they took a group photo of us and also took our fingerprints, they untied our hands, to lead us as if to escape to the rest of the corridor, which had two doors on the sides and a third one in front, above which were marked the numbers 1 on the right, 2 on the left, and 3 in front, respectively.

While the two rooms on the side, namely 1 and 2, were each raised by a flight of stairs and paved with boards – the well-known Shkodra stoves – the one with number 3 stood at the lower level of the corridor and was paved with cement, perhaps a former stable, which extended as long as the entire building, that is, as long as the two rooms with numbers 1 and 2, plus the width of the corridor. Ruzhdi Çobe, Thabit Rusi, Qazim Dervishi, Lec Barbullushi, Ruzhdi Baja and Refik Bushati, were put in room no. 1, in the one with number 2 they put Ernest Përdoda and Xhelë Baci, while in the 3rd Remzi and Xhevat Qukun, Tomë Sheldi and me.

When we entered the room to greet each other, we noticed that there was immediate complete silence. As we would later learn, something like this would happen whenever new prisoners were admitted to a prison cell. The prisoners in the cell would stand in front of their beds, wrapped up as they had been since morning, and leaning against the four walls of the room, looking at us curiously. It was not difficult for us to read in their faces at that moment the pity they felt for us. On this occasion, they would later say to us: “We were impressed by you because you were young.”

The entry into a cell of a new prisoner marked an event for its inmates. In such a case, usually the room would suddenly fall silent, and the prisoners, with their eyes and whispering to their comrades as if in a whisper, would search day and night to find out who the newly arrived prisoner or prisoners could be. There are some prison rules of their own, which have become tradition. It happened that in a room a new prisoner would find his relatives or acquaintances, and in such a case, they would be the first to meet him, ask him briefly about his imprisonment, whether he had suffered during the investigation or not, about the people in the house, if he had had contact with them, and very quickly, this information would then be transmitted word of mouth around the room, thus quenching everyone’s curiosity.

The “ritual” would continue with another category of prisoners, with those who, after having found their connection with a parent or relative of the newly arrived prisoner, would go to introduce themselves to him and without delay, as if not to bother him any further, would part ways with him, leaving the line for others, and also, having reserved the other questions for later. In a prison cell there are also those who would shake the hand of the new prisoner, even though they had not met him or his people, and like everyone else, on that occasion, wish him health and a speedy release from prison.

There is then a small category of prisoners, weak in spirit, who, crushed by prison, illness and age, or even because of their type, do not want to know “who enters and leaves there”, who see only “blackness” and who, in solitude, painfully drag out the days of a prison that, after them, will never end. There, in addition to the villagers of the Shkodra plain, the mountaineers of Malcia e Madhe and Dukagjin, the areas of Mirdita, Puka, Tropoja and Luma would also have a majority of representatives. In addition to some of the friends with whom I was put in this room, I would also find Ramadan Sokol, the brother of my friend, Hodo Sokol, who would stay close to me and would guide me through that prison room with perhaps over a hundred people.

I found Ramadan reading “Rilke”, as well as engaged in collecting folklore, a job he continued with passion. Wasn’t that prison a gold mine to be explored! I had something to benefit from Ramadan Sokol, with a decade of life more than me, with an immense number of books read, to benefit from Florence, where he had studied, from the connections he had with the elite of the young intellectuals of the time, among them also with Qemal Draci, with whom he had been intimate, without failing to point out his energy, talent, as well as his will and his strong character when it came to him.

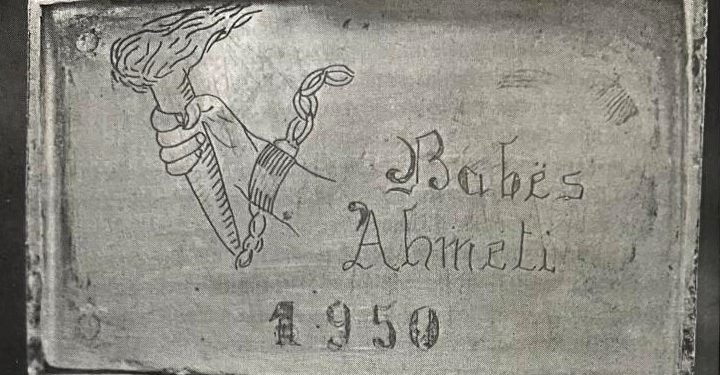

Ramadani, who had studied flute and composition in Florence, with his artistic talent, would also take up painting in prison, and with wood carving and aluminum foil, he would produce miniature objects from peach pits such as “pashamma”, “baskets”, etc., which would be taken out as prison gifts for family and relatives. Ramadani would also take up embroidery, that is, he would also work on the “loom”.

Through books, he would exchange and exchange with his fellow prisoners, such as Drita Kosturi and Terezina Pali, who happened to have a room with an entrance from the outside – called the “women’s room” – and with whom Ramadani would carry out his correspondence, using a “code”, a code that would, for example, the word “patience”, he would put a faint dot with a pencil, under the first letter “d”, so that it would have the page of a book, to continue with the letter “ư”, which came after it and so on, until the word “patience” was complete, to continue in this way with all the words that a letter of his would have.

At the end of our long room, there was an exit to the bathroom, where my friends and I, after a year and a half of not having washed, would pour water on our swollen bodies for the first time. At dinner, a man of about thirty years old, who although he had graduated from pharmacy, but who served there as a sanitary and as a doctor, pulled my pants elastic without warning and in front of others, released two or three fists D.D,T. inside them, and he left laughing, making me laugh out loud too. The D.D.T. was thrown at us for lice. The person who performed that service had been the pharmacist Elez Troshani himself, whom I had once recognized by face, but that night, his shaved head and a turban we put on him anyway, had erased the traces of the good appearance he had had when he had been free.

The prisoners we found there were generally old, or sick, incapable of physical work, while the rest of the prisoners, – who constituted the majority – happened to be sent to the Orman-Pojani labor camp, in the Korça area, from where they would be returned to Shkodra prison during the month of November, at which time we would also be moved from the New Prison to join them in the Big Prison.

This prison cell, with light and many good people, after a year and a half of a dark dungeon, would give me health and revive me internally so quickly that it would seem to me like I was in heaven. At a certain hour in the evening, we had the obligatory reading of the newspaper “Zëri i Popullit”, which was usually done by Andro Petrovic, a gentle and very kind man, but whose face, for some reason, would always be sad. Twice a day, for an hour, we would be taken out to the large yard behind the building, an exit that we young people would use to play basketball with football goals without posts, and we would be divided into two teams, one representing room 1 and 2, and the other our 3rd.

According to the regulations, once a month we had the right to write a letter to our family, in which case we would be obliged to write on the envelope, not without some concern, as the address: “Prison of the Friends of the People”. Once every fifteen days we would meet with our family, and once every fifteen days we would receive food from them, but I would receive food every week, because one of my sisters, once every two weeks, would cover them with a sheet, so that she could bring me food in the name of Bajram Xhemali from Kalasë se Dodës, pretending to be one of his people, and on that occasion, meet with him. Meeting my family once every two weeks would be another good thing for me, after a year and a half of isolation. Those first meetings with my closest people, including Sime, would give me great pleasure.

Our room no. 3 was rectangular in shape and, as it were, the leaders of the country had settled in it – although it was close to the exit to the beach – the elderly, who also had physical problems, such as the former soldiers Luigj Mikeli, Hamza Kuçi, Zef Martini, Paulin Prendushi and, after them, the younger ones, such as Teufik Bekteshi – who often suffered from severe collarbone pain – and then Hamid Nurja, Malo Kraja, Malo Cani, Smajl Elezi, etc.

The above-mentioned people would be among the “masters” – that’s what the masters of the game of backgammon were called in prison, which, it seemed, had been the preferred game for soldiers and civil servants during the reign. Despite the rule not to move from one place to another, there was the opportunity to move and play chess, backgammon and dominoes, until it got dark, and there were such rivalries that justified the interest of a number of other prisoners. There were cases when the losers, for fun, carried on their backs not only the winners, but also those spectators who had followed the development of their game.

From the first night of my arrival in this prison, they had placed me between Ramadan Sokol and Pjetër Saraçi, the older brother of the former history professor, Angjelin Saraçi, who in the summer of 1944, together with the young ballistics men of the “Besnik Çano” battalion, had gone to Kosovo to fight for the defense of Albanian lands from the Serbs, and when, at the moment they were leaving, a former student of his would ask him as if for fun; “You too, ballistics professor”?! and he, in turn, would answer: “No, no, national”.

Pjetër Saraçi, to my delight, would start performing some of his “numbers” the very next day. After realizing that I was tired of his tobacco and dust, he could hardly wait to not only direct the smoke – supposedly unintentionally – towards me, but leaning against me as if it were a pillow, he would shake the cigarette dust over his chest like a roll of tobacco, over the shirt that his wife had brought him that day, clean and ironed, and on that occasion take serious and indifferent poses, as if he didn’t care about my gas, and the others around him. Memorie.al