By Ahmet Bushati

Part Three

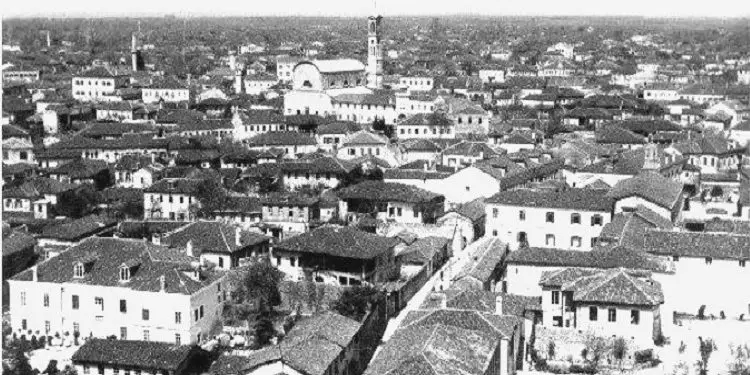

Memorie.al/ After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Shkodra in the Early Years Under Communism

Even we little ones are in the war!

During the years 1942-43, the National Liberation War had attracted most of the high school students. Within this period filled with numerous war events, we were also growing up, and, so to speak, we were becoming more and more part of a great war, shattered into thousands and thousands of endless points of gravity all over the country. It was enough to convince the mind that all people were affected by the fever of war. As time passed, our reaction was becoming more and more conscious, active and concrete.

Thus, in an organized manner, we would begin to gather secretly in friends’ houses, and as needed, in meadows up to the lake shore. In the name of the war, we would write slogans in the slang of the time, in visible places of the city and, at night, we would distribute tracts under the doors of houses. Assigning you to the duty of observer around a house where an illegal gathering was taking place, or in this role accompanying the Shkodra district courier, Haki Llazanin, to the S.A.T.A. agency every time he left for Prizren or Durrës, or even delivering a parcel, even an insignificant one, from one base to another, would seem to you to have accomplished a valuable task, one that would fill you with joy and pride.

I would feel very proud if one day the leader of the group I was part of, Jonuz Tuli, came to my house, handed me a hyacinth – a canister – full of tracts in Italian, and said to me: “Because of the trust we have in you, it has been decided that you distribute tracts throughout the Italian army, starting from the first barracks with Italian soldiers, just behind the sports field, and to the last, somewhere near the Middle Bridge. These tracts are of particular importance, because they call on Italian soldiers to desert from an army in the service of fascism and to join our freedom fighters in the mountains”.

And that summer afternoon, to my greatest honor, I carried out that task, according to the order I had been given. We would perform, as the case may be, other services, but the demonstrations would mark very moving moments for me, for the anti-Italian slogans with a strong patriotic tone, which on that occasion were courageously shouted by the ardent demonstrators, as well as for the patriotic songs that were sung with special pathos, which together would allow us to experience an unrepeatable state, patriotic exaltation.

Two in particular, among the several demonstrations that took place in Shkodra, would leave me with indelible impressions for the rest of my life: that of February 22, 1942, held on the occasion of the anniversary of the fascist “Marcia su Roma”, when in the ensuing scuffle, they killed in front of everyone, the communist Vaso Kadia, – after he, in turn, mortally wounded an Italian carabinieri officer – who would die a few hours later in the hospital.

But perhaps the greatest impression I had on that demonstration was the courage of the student Vehbije Barbullushi, who, despite the rifles that were fired upwards by the Italian carabinieri, placed herself at the forefront of the demonstration, in order to intimidate the demonstrators, and despite the fact that they were constantly beating her and dragging her by the hair, she would not let go and would never let go of the national flag of the demonstration.

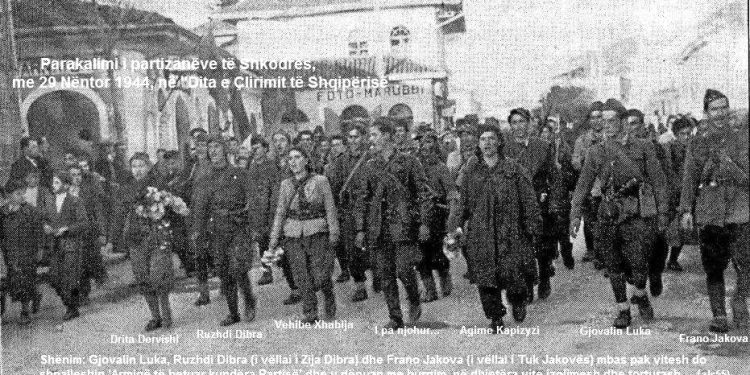

Another demonstration to note was the one held on July 26, 1943, undoubtedly the largest of all the others, in which all the parties of the time would participate together, and this, because of a climate of rapprochement that had been created during those days of the Mukje vigil. The signal for the beginning of the demonstration with “Come gather here, here!” that, having started from the Municipality, would be given by the National Front’s Ramadan Kazazi.

After a few dozen meters of that very imposing demonstration, both for the large number of its ardent participants, and for the patriotic songs, with the powerful sound of which it would seem as if the entire sky above had been filled, that enormous avalanche of people exalted by the calls for freedom, would be surprised, but would not stop, when suddenly a long line of Italian cavalry appeared in the distance, walking towards it with the leap of an angry military opponent, as never before.

After those soldiers mounted on high horses and surrounded the last rows of demonstrators, in order to disperse them, they would fire several rifles upwards, and sometimes downwards, in which case it was said that four people were injured, among them Adem Kombi, Vehbi Ramadani, and that on that occasion, Mustafa Dervishi, the secretary of the Youth of the ‘National Front’ for Shkodra, and one of the most prominent young intellectuals of our city, who only a year earlier had graduated with distinction in Italy in architecture, was killed.

Any meeting with the partisans, realized somewhere outside the city, would also mark one of those interesting cases of wartime, and this for the military uniform they wore, for a long rifle they carried near them, or even for a bomb they might have hung on their belt, and above all, for many enthusiasts who told them about the mission they had undertaken, making me, and all others like me, believe that they were the only ones who carried within themselves the wonderful mystery of freedom fighters.

When you are young and your country is conquered, you are so captivated by the romance of the fight for freedom that the beauties of your soul are greatly elevated by it, you will attribute it to everything around you, even nature, which will seem to you as if it too was involved in the war. Thus, the mountains that you see from afar, you cannot separate from the idea that freedom fighters, armed with weapons in their hands, were roaming through them, ready for war and any sacrifice, and that those houses that seem small and sparse from the city, were, without a doubt, shelters for them.

In those days, almost for days, we would cast our gaze with special sympathy towards the bare hills of the village of Domën, because in the early spring of 1943, on the mountain above it, the first attempt of the partisans with the fascist militia had taken place, in which the young Tom Kola, a former high school student and boarder of “Our Mountains”, had fallen. Likewise, the nights in the city, like its winding streets, would seem as if they too were participating in the war, hiding and protecting the fighters from enemies and dangers. They were convinced, then, that everything had become an integral part of the war and, in its function, that the very mirage of a future free Albania, seemed to them a somewhat imperceptible dream, and as something not very likely to truly become reality, precisely because of its unique beauty.

Such was that dizzying war, that the better and more sensitive its fighters had been, the closer it would lead them to danger, even if the cause was not only the liberation of the country from the foreigner, but also the realization of a “blind”, however absurd and cruel for all humanity, but even then, it was believed by a part of the youth as a savior, as after which humanity would supposedly be finally liberated, from the numerous injustices accumulated from time to time!

Otherwise, how can one explain the large-scale participation of the youth in that war and their unreserved dedication to it, starting from the best, like Qemal Stafa and his friends, who, as long as that war lasted, as its protagonists, would put into action the most positive sides of their beings, regardless of the fact that they would remain in conditions of dictatorship, when as is already known, a part of them, in due time, would become its victims, while the other part, which would naturally constitute the majority, would change to the point of complete disfigurement.

Times come with their own peculiarities, which for some people, for better or for worse, reveal and develop their characters even more. Thus, there had to be a war for freedom, so that martyrs and heroes would appear on the scene, just as back under the dictatorship, along with a countless army of hypocrites, crawler and spies, martyrs and heroes would appear again. So, just as during the War a great enthusiasm had taken over the youth, to the point that a part of it seemed as if it had ceased to live for itself, so it would happen to us idealistic young people back then, when we would suffer in communist prisons and camps!

A cousin of mine, Naim Gjylbegu, precisely because he had come into life with the inclinations of a good man and had grown up in a distinguished civic environment, he would devote himself all the more to the war, even without the need, in any case, to expose himself to danger, except as he could affirm to himself and others, his loyalty to the cause, outside of which, for him, nothing else existed at that time. Likewise, another cousin of mine, Malo Bushati, who was returned to the city on a mission from the partisan group, would shed tears when he heard about the fighting in Domni, which had taken place in his absence.

Thus, the youth of that time, above all, were only driven by feelings, and with few exceptions, especially up to Mukje, no one could believe that their war was a mistake, let alone that they themselves were playing out the most terrible tragedy for their country. Likewise, excluding the Yugoslav emissaries near the “General Staff” of the National Liberation Army, as well as Enver Hoxha and anyone else, no participant in the War, should have believed at that time that their just war, with all its human sacrifice, would generate one of the most savage dictatorships for their people.

Lest you get confused by the consequences of that war or the metamorphosis that many of its participants would undergo, to illustrate the above and, as a sign of deep homage, I will add that that war would not have ended without the sacrifice of a friend and cousin of mine, only two years older than me: He was only 16 years old when he held the partisan’s long rifle on his fragile shoulders and, as such, was perhaps the youngest of the “Perlat Rexhepi” battalion. A year later, he would be caught by surprise by Albanian tools in the service of the Germans, and the latter would internecine him in Pristina, where he must once again have been one of the youngest in that infamous camp, and undoubtedly the youngest within a group of thirty people, who would one day be separated to be shot.

So, on the last night of his life, at a time when everyone else was anxiously awaiting the dawn, when they would even shoot him, he, for the beauty of his youthful spirit and the ideal of freedom that had inspired him and given him so much courage, longed to carve his last words on the rough surface of a stone on the wall: “Nuri Bushati, 17 years old, from Shkodra”, the name, age and place with which he seemed to seek not to be dissolved into oblivion, words that still continue to sound today, as his distant greeting to the people and friends he had left behind, a greeting that has always resonated with me and still resonates with me, and as a gentle protest against fate itself, because in the end, a life of only seventeen years was too soon to be buried, regardless of any altar that might have been built for him. wait for it.

It is also my obligation to remember on this occasion Professor Mark Ndoja, who during the school years of ’42-’43, had taught us Albanian and Latin. I would have been impressed by that man and professor when he, with red eyes and eyes narrowed by myopia, through the reading and interpretation of verses from “The Highland Flute”, – numerous parts of which he had given us to learn by heart – sought to ignite among us those patriotic feelings, which at that time should have been the goal in itself of his work with us.

When once as a class we boycotted the lesson for political reasons, the next day he, as our professor-guardian, although he was afraid of our possible mistakes, would reprimand us in a tone that was both advisory and friendly: “You should attend school without fail, it is we, the older ones, who have the duty to think about other things too”!

What war was Albania coming out of, that day when the partisans were triumphantly entering the cities?

Although the subject of this paper is not the period of the war, nor the war itself that our people waged against two successive invaders, I see it appropriate to briefly point out the main causes that ultimately led that war to the inevitable and total victory of the communists, causes that, in my opinion, consist of: The fascist occupation brought about the fatal coincidence of our national interests with those of the communist movement, from which that “Movement” benefited and developed very successfully under the umbrella of the war for liberation, that is, having unfurled the nationalist flag of freedom and independence and not its real program, which it would reserve for later, for the right time.

Thus, the communists, without any mention of “socialist revolution”, “establishment of dictatorship”, “nationalization of the means of production” or “class war” or “war against religion”, would be the first to demagoguery, break every ideological, regional and social boundary, to issue a call for the unification of all Albanians around their war, a call to which the Albanian youth, ignited by the occupation of the country, could hardly wait to respond massively and enthusiastically, and in the process, to write pages of rare heroism, while most of the nationalists, with few exceptions, such as those of Abas Kupi and Muharrem Bajraktar in the North, or of Safet Butka, Hysni Lepenica and Abas Ermenji in the South, who with a squad of their own, would fight the invader in time.

While others, in general, due to their political myopia, would continue to vacillate between the dilemma; “whether to fight an Italy that had returned Kosovo to us after fifty years of separation”, as well as the fact that a lot of precious time would have to pass until they were convinced that the victory of the Allies was certain, in contrast to the Greek nationalists, who through war enabled the intervention of the Allies in Greece. In addition to the above, the Albanian nationalists, due to the education and culture they had, and especially their civic and patriotic formation, did not embrace the war and its harsh laws in time, also for reasons of debt, having expressed that; “Don’t burn our poor villages”, and “Brother must not kill brother”, etc., and this, even when the communist forces were about to launch the final attack on them, Enver Hoxha then, with the help of the Anglo-American allies – who were opponents of the “Axis” forces – would take care that those shortcomings and vacuums created by the nationalists, he would exploit in such a way that one day he and his communists would sit alone around the table of the victors.

I think that the external factor would not have been so decisive in the inclusion of Albania within the Soviet framework, if the Albanian nationalists had come to the country, through war and in time. On the other hand, if they had been united among themselves and it had not happened that some of them, like Abas Kupi in Kruja, Ismail Petrela in Tirana, Mestan Ujaniku in the districts of Berat, the Kryezezët in the North and some others, were forced to make their patriotic contribution within the framework of the “National Liberation War”.

On the other hand, Russia and Stalin himself did not show any particular interest in Albania during the war, so they would not necessarily insist that this small country with a non-Slavic population become an integral part of their sphere, which could have happened if the war, as a result of the participation of nationalists in it, had not been dominated by communist forces.

As for Shkodra, it can be said that it generally supported the war in one form or another, but that perhaps as a reflex of its somewhat special history, as well as its strong worldview and tradition, it did not take sides with either party, although the doors of every house, including those of the functionaries of the time, would have been constantly open for anyone to be followed by the invader and his tools.

But for one of its peculiarities, contrary to what was happening in the south after Mukje – where fratricide was the order of the day – in Shkodra, apart from a hardening of propaganda by the communists, where their stale and aggressive slogan prevailed; “with us, or against us”, nothing else would happen, that is, no act of fratricide would be recorded, with the exception of the murder in the Valbonës Gorge, of Father Lekë Luli, an exponent of Legality, and of a twenty-five-year-old ballistics officer from Përmet, by two partisans of the “Perlat Rexhepi” battalion, one of whom had the pseudonym “Harapi”, an event that would occur immediately after a meeting that a group of partisans of that battalion had held in Sllatinë, Dibra, with the partisan leadership of the 1st Division, on its way to the North.

It was this meeting and this occasion that had inspired those partisans of Shkodra, both for the above act, and to go to the aid of a fifth Montenegrin brigade, called “proletarians”, in its fight against the Albanian nationalist forces of Plavë – Gucië, called by them, “reactionary”!

Finally, one day, that great war would end, having returned freedom and peace to all the countries of Europe that had been occupied by the “Axis” forces, which unfortunately would not happen to the peoples to its east, who would then fall under the rule of totalitarian communist regimes, including Albania, with whom fate would prove even harsher than with all the others, perhaps also for the most banal fact, that at its head would be placed by the Yugoslavs and in their service, a mediocre, but also very ambitious and perverse man, by the name of Enver Hoxha, who for four decades in a row would keep a people under his feet and abandoned by the world, asking them to call “violence” “justice”, “privations” – “freedom” and the deepest “misery” of life – “happiness”! Memorie.al