By Namik Mehmeti

Memorie.al / A life that has brought him closer to the pleasant years of childhood, years of suffering and disappointment, those under the communist dictatorship, and not a few, a full 45 years, almost half of the years that he carries on his shoulders today, and more than 30 years of his third age in emigration, in Florence, Italy, years that, although with sacrifices, have given him a renewal of energy and a life that has left behind those that brought him closer, the communist regime, but years that are unforgettable. I met Agron just as I had decided to live as a family, like all Albanians oppressed by that bloody system, here in Florence, when they introduced me in the bar and buffet at the ‘Fertrinelli’ bookstore, in “Piaca Repubblica”.

He immediately brought me closer to the desire to communicate as if we had known each other for years. A somewhat hoarse voice that had left him with an illness that he defeated here in the hospitals of Florence, under the care of Italian doctors. “I was not afraid of the pain of this illness, having the faith that God, after having taken care of me during the 8 years of Dante’s hell, in the prison of Spaç, here I am guaranteed by Italian medicine” – says Agron Kallejxhi in the first conversation.

– “From Kallejxhi, a family with a voice in Gjirokastër”, I tell him.

– “Grandfather Sabri Kallejxhi has a well-known and archived story in the history of this city, returning from Istanbul, where he had studied, helping to publish the first primers for teaching the Albanian language under the Turkish occupation, opening Albanian schools, with a valuable contribution to the Society of Printing Letters in the Albanian Language alongside the well-known patriots Sami Frashëri, A. D. Prishtina, Kostandin Kristiforidhi Vaso Pasha, A. Kallejxhi, Seremedin Toptani. He was imprisoned by the Ottoman Government, participated in the raising of the Independence Flag on November 28, 1912 in Vlora, taking over from Ismail Qemali, as a teacher in Durrës and later as a teacher of the Albanian language in his hometown, where the government of Ahmet Zogu granted him a pension until the day of his death on February 7, 1929.”

– “you said that your grandfather contributed to the education of his children by spreading them to the four corners of Europe. Where did your father, Masar Kallejxhi, study?”

– “Masari chose the branch of agronomy by studying in Florence after winning a scholarship from the Zogist Monarchy, specializing in olive cultivation.”

– “So many youthful dreams are also connected to Florence”?

– “That’s true, I even went to Florence when I was three years old with both parents, to stay in Italy, but my father wanted to reward all his scientific knowledge to his homeland.”

– “In the Zogist Monarchy, I was entrusted with duties up to the Ministry of Agriculture, with the establishment of communist power, as the life of a European intellectual like Masar Kallejxhi took its course”?

– “He did not trust the government of the dictator Hoxha, after seeing how the cadres who had studied in Europe were being treated. They hired him in one of the fruit-growing directorates in the Ministry of Agriculture, he devoted himself to work with all his heart to develop olive cultivation on a scientific basis, but he was put on the list of intellectuals who had European culture.

Without even six months having passed since the ‘liberators’ entered Tirana, the Military Court on 23.04.1945, sentenced him without any charges, staging for espionage groups in the West, to overthrow the communist government, to 10 years in prison”, – the 95-year-old recalls today, what suffering the Kallejxhi family went through when all their assets were confiscated, leaving them in the middle of nowhere. His mother had to sacrifice a lot to raise her five children.

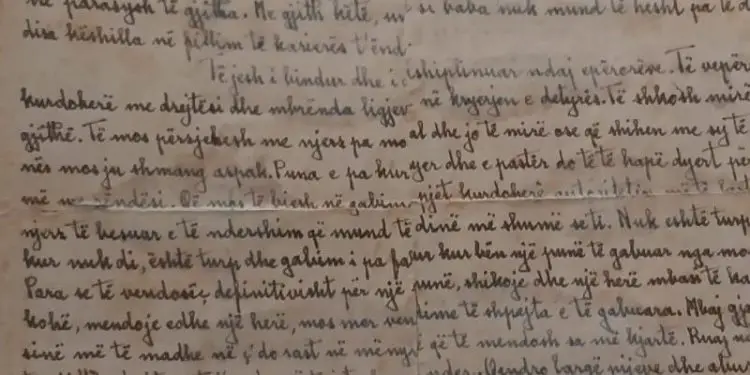

– “It is a letter that I have kept among many memories. My father advised me to be careful in my relationships with friends at work and in society, to choose friends who are better than myself. To be obedient and disciplined towards my superiors. To always act fairly and within the law in carrying out my duties. To get along well with everyone. To not work with people who are immoral and bad or who are viewed with a negative eye. Do not avoid work at all. Unsparing and clean work will open the doors to more important tasks”.

And Agron feels proud of those beautiful youthful years in the company of famous artists and athletes such as Vaçe Zela, Ferdinand Xhilaga, Gol Shkreli, Rudolf Stambolla, Kastriot Dushi, Luk Kaçaj or Qemal Vogli, Fatmir Frashëri, Pal Mirashi, etc.

But the State Security followed him step by step, targeting him as a sympathizer of fashion in clothing, for owning a motorcycle of the brand “Java”, a car “Masovic”, for evenings at the Tavern of “Dajti”. These were enough to formulate the charge of agitation and propaganda.

At the age of 41, on August 1, 1970, upon entering the house, they put handcuffs on him and after an investigation lasting more than three months, investigator Sali Budo formulated the charge, as “a dangerous person, he speaks foreign languages, Italian and French, he had plans to organize anti-communist cells, since his background as a Zogist family and with a politically convicted father”, were enough to formulate the charge.

The decision of the panel of judges headed by Shegushe Hakani and prosecutor Hava Bekteshi, Agron was sentenced to 8 years in prison, years that he spent in the hellish prison in Spaç, bringing other misfortunes to the family.

“Likewise, his wife and daughter were forced to divorce, his sister, Flora, one of the most talented dancers of the Opera and Ballet Theater, had created a family with the brother of former minister Vasil Kati, which had brought dissatisfaction to his parents after the death of his father, his mother Feruze, a woman of sacrifice, felt my imprisonment very much and died without seeing it.

– “And the eight years of Spaç are a chapter…”!

– “The one who entered there before thought of death and could not even dream of freedom since the re-sentences were only for a word of mouth that even the walls of the dungeons accused them of. I was very attentive in every communication and always remembered the lines of my father’s letters that he sent me from prison. The first entry into the underground shocked me a lot, not because of the hell that it presented to me, but because of the people who were disfigured while working naked, just as they had come out of their mother’s womb. For a moment, not even the words that the group leader told me about the work I would do, did not bring me out of the state of that shocking friend in this Dantesque panorama. ‘Don’t be shocked, you will quickly get used to both the work and these scum like you, who should not be spared bullets’, – where I only remembered his words, because at the moment I did not catch his name when he told me.

I started digging in the rock, a wagon stood nearby with a mouth as if it were swallowing not minerals but human lives. Pistols, digging and filling shovels, and numb hands that had to push the wagon. And at that moment Agron feels a tightening in his breathing, follows a few drops of water, fills with breath and says: But when you think you are finished, a ray of hope and light comes to that desolation. My acquaintance outside the prison with Kujtim Zhari, who was assigned the task as head of the Technical Office, recognizing my profession as a mechanic, took me out of that slavish work, to deal with the elimination of defects in motor vehicles and those of transport”.

But Agron says among other things; “those who helped me the most morally were the political convicts, from well-known civic families from Tirana, Shkodra, etc. The company of Fadil Kokomani and Vangjel Lezhon who tragically died in firing squads, with the wise and speechless Shkodra resident Hodo Sokoli, with the legend of Albanian football Qemal Vogli, with Nevruz Serezi and Gezim Çela, whose death a few months ago re-awakened memories of those years where friends, like Gëzim with his unyielding stance against violence and inhuman treatment by police and guards, like Hajri Pashaj with his friends gave us courage not to lose”!

Today, Agron, after turning 95, remembers those sufferings of family loneliness, even in prison because no one came to visit him, but he was not alone.

– “Agron, even though 53 years have passed, is it difficult to erase the tragedies of Spaç from memory”?

– “There in Spaç I saw that the political prisoners were of the same blood that boiled with hatred for the dictatorship communist, and the criminal Enver Hoxha, where despite the inhuman living and working conditions, not to mention the physical and psychological torture, the miserable situation that this dictatorship had installed even outside the siege of Spaç towards our fathers, mothers, sisters and brothers, they did not betray their ideals.

Those three days of that revolt, the convicts found themselves free, having given a warning to the Enver regime, but the execution of our comrades Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Dervish Bejko and Hajri Pashaj, the arrest of dozens of others, did not extinguish the hatred and resistance of the prisoners, which required the rise of the State, led by the criminal Feçor Shehu”.

– “You are 95 years old and one of the rare witnesses of this event that has entered history”?

– “I try to remember the fellow sufferers of Spaç, but the stay away from Albania for 33 years, the lack of contact with these fellow sufferers make it difficult for me to remember in detail the years of my stay in Spaç prison, but what I convey to my interlocutors here in Florence is the stoic attitude of the prisoners who no longer counted life in the face of the bestial cruelty of the police and guards, fighting them for injustices by denying even a morsel of bread and water.

Here in Florence lives another fellow sufferer who has passed the limits of my age. I am talking about Cardinal Troshani, with whom I spent several years in Spaç and for me he remains an epic example not only of his physical resistance to withstand 30 years in the prisons and labor camps of the communist dictatorship, but also of the discrimination of that regime after leaving prison”.

Although Agroni has recreated another married life here in Florence, with Mrs. Teuta Tërshana, a daughter of the famous Dibrani Tërshana tribe, where her father Ibrahimi served his sentence in the prisons of the dictatorship, as an enemy of the people, only because he was a nationalist dedicated to an Ethnic Albania, he feels very comfortable especially in terms of health care, but he is also kept alive by those memories of the family that was terrorized and massacred, only because they dreamed of freedom and the Western spirit. He cannot help but return to the memories of his youth and now in his old age.

A photo, one of many that he keeps as a keepsake. At the age of three, he is with his parents Masari in a park in Tuscany, where behind them is a massive white stone. My mother had told me something about this somewhat mystical photo.

“Italian families turned to this stone to bring good luck in life, and my parents also wanted to capture a memory from this park. When I came to Florence, after I managed to set foot in the University where my father had studied, the house where he had lived as a student with his Albanian friends, I set out in search of this mystical stone. Going towards Umbria, I had an address marked on the back of the photo; ‘Spoleto 1932’. I met many elderly people in that endless garden, asking for the exact address and showing them the photo, which made them curious to learn about my photographed family.

And after walking a long way, I came across a lens that captured a photo from 1932 and many elderly people who were relaxing in the beautiful nature of Tuscany surrounded me to learn what history this photo hid. I did not miss the opportunity to repeat this memory, in a photo, after nearly 60 years had passed, but of course without the presence of his parents, but aware that I was fulfilling a bequest from them”!

Continuing the conversation about the years in prison and after his release, Agron again feels a tightness in his soul.

– “Free, I was free to walk around Tirana, to go to those places where I used to meet my friends and then when everyone gathered in their families, I was wandering homeless, after the communist state had confiscated the house where a high party official lived. I was looking for a job to make ends meet, but wherever I knocked I found closed doors. ‘Only a shovel worker is your place’, – was the answer of the neighborhood council, of the cadre bosses, but the worst was when the ones I had had many friends and comrades, when they saw me, changed their ways, or turned their backs on me.

After three months of staying with my sister, I managed to find a solution and for this I thank Hysen Shahu, who intervened to arrange a job for me in the municipal enterprise in my profession as a mechanic. At one time, they even offered me an apartment, solving the housing problem.

Very convicts who have suffered in the prisons of the communist dictatorship such as in Spaç, Qafë Bari, etc., have achieved the freedom they dreamed of after being re-convicted, more than once. And this right to re-convict was held by people without feelings and without soul, real criminals. I happened to meet these carcasses when the dictatorship had collapsed. It occurred to me on a more urban journey in the outskirts of Florence, to see the portrait of such a criminal who, when he was convinced that I knew him, and wanted to take revenge on him, he went down to the first farm and ran away, which attracted the attention of passers-by”.

As the conversation always turns to the reprisals suffered by the prisoners of Spaç, for a moment Agron again turns his attention to the photo archive, where a photo shows the botanical garden of ‘Pistoja’ in Tuscany. Agron was also invited among the guests at the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Agricultural University of Tuscany.

– “There were emotional moments when I saw in the exhibited photos the portrait of my father, Masar Kallejxhi, together with students from European countries where the names of Masar’s compatriots, such as Lodovik Gajtani, were not missing. In the company of the well-known botanist in Tirana, the late Tomson Nishani, I managed to create an album with such facts and images of the University where my father graduated”.

Agroni a life full of twists and turns and surprises, at the age of 95 where we wish him the most ordinary in such celebrations; “even 100 Agron”, he, thanking us, has something to express with a significant subtext:

– “I feel good here in Florence, I have all the conditions and what is most important is that I am respected wherever I go, perhaps because of my age, perhaps also by some and not a few of my Italian friends, who have kept in their memory my conversations about the suffering of Albanians, especially of intellectual families under the Enver regime. And life here in emigration often confronted me with surprises, such as meeting compatriots from Shkodra to Gjirokastër, and with Italians who were born in Tirana and had turned their backs on their homeland due to the inhuman and immoral persecution of the communist dictatorship.

I was on a medical visit in one of the clinics here in Florence and a doctor in a white shirt approached me and said; are you Albanian? Apparently, he had heard me speaking Albanian with my wife Teuta. I answered in Italian that it was so. With very emotional and longing with him, he said, we Albanians were born in Tirana and at the age of three, together with my Italian mother, we returned to Florence.

After exchanging cell phone numbers, we had a meeting where he told me about the tragedy of the Allamani family, the shooting of his father, the vicissitudes of returning to Italy, the return to Albania after the establishment of Democracy, to find his father’s grave, which he had accomplished with the help of his father’s relatives in Mat. Although he was tired of the bureaucratic obstacles of the Ministry of Interior administration, he was very happy to have realized his father’s reburial, in the presence of many Matjans. And this freedom that I am living in Florence, I had dreamed of enjoying with my parents, brothers and sisters in my homeland, but the Enverian dictatorship stifled these dreams and desires.

However, these sufferings have not extinguished my longing and love for Albania and Tirana where I grew up, but even this Democracy in long transition has not brought me closer to what my honorable parents left me, the property, and I never felt any remorse from the rapists and perpetrators of the misfortunes that not only brought me and my family, but all the persecuted, from the communist executioners, or the opening of the files and their punishment. ”

“Agron even 100”!

He puts his lip on the gas and says: “I have never measured my age in years, but only with faith in God, to spend a peaceful old age. A chance acquaintance in a medical clinic with an Italian doctor brought back many memories for me over the years. While I was talking to my wife Teute in Albanian, the doctor in question had fixed his gaze on us who were sitting on a bench waiting for the visit. He took two or three steps towards us and, apologizing for entering the conversation, said: “From the language you are speaking, I understood that you were Albanian. I have a lot to say about your country, a country that unfortunately I remember for a tragedy of my family and myself. This is not a conversation that is consumed in a casual meeting. If you would like to get to know us even better and it is not surprising that we are probably known by our ancestors, since I also have Albanian blood in my veins.

After he introduced himself as Allaman Allamani and we exchanged cell phone numbers, to arrange a meeting, I had come across this surname Allamani in Florence, when I was interested in knowing everything about my father, so I did not hesitate and asked him if you were the son of Isuf Allamani from Mati in Albania. ‘Yes’ – he said in a longing voice. I did not delay but three or four days and our meeting became a reality.

A story that contained in its content the joy of a nationalist Albanian who had started a family with an Italian girl, who had responded to his first love with a ‘yes’, to the charming boy student at the University of Veterinary Medicine in Florence from Albania, without shyness or conditions, a marriage that had the greatest joy, when the first child was born, dreams of a life built with work and with the sweat of his brow, but dreams that ‘had remained in the drawer’.

‘I grew up without knowing my father. I was no more than two years old when the government of Enver Hoxha punished my father by shooting him. And why? In Xhafezotaj Isufi was a farm entrepreneur. In a check by partisan units looking for nationalists from the Shijak family Dellialisi, who were friends in Isufi’s house, he intervened forcefully, preventing their arrest. They were friends and for the sake of canonical customs, they should not have become victims on the doorstep of Isuf Allamani. And as is known, he chose the path of self-sacrifice with his friends, leaving no trace of the grave.”

During his occasional meetings with Dr. Allamani, Agron also became acquainted with an “adventure” of his friend. Eager to learn about his father’s fate, keeping in mind what his mother, Fiorentina Leonella, the Italian who had fled with her son from Albania to Florence, after the tragic act of Isufi, Dr. Allamani, in the wildest years of the communist dictatorship, had joined a group of Italian tourists to visit the ‘land of eagles’. At the ‘Dajti’ hotel, he had entered into conversation with his Albanian companion and translator, telling them that his coming to know Albania was also to fulfill a bequest left to him by his Italian mother and to resolve a concern that he was suffering spiritually, to find his father’s grave and to learn something more about his life.

This request by Dr. Allamani fell like a bomb in the closed premises of the Hotel ‘Dajti’ and within 24 hours Dr. Allamani was returned to Florence. With the advent of Democracy, he managed to realize his dream, finding Isuf’s grave, his reburial, thanks to the help and commitment of the Matjane families that have blood ties to the Allamani tribe and the Shijak families with whom the intellectual graduated in Florence, Isuf Allamani, had a friendship”, – Agroni concluded his conversation.

And he turned his first acquaintance with Dr. Allamani into a brotherly friendship. But even Dr. Allaman Allamani, remembering the ordeal of his mother Fiorentina’s suffering, after the shooting of her husband, the raising of his son who wants to know his father, has chosen and maintains his friendship with Agroni as a privilege, precisely in that saga of suffering and horrors that Albanians have gone through under the claws of a dictatorship that approaches the inhuman treatment that Hitler’s Nazis inflicted in the death camps in Auschwitz.

We often meet as a family with the Kallejxhi family, where we do not There are also compatriots from Tirana, Shkodra, Kavaja, Elbasan, Durrës, Dibra, etc., who surround us and express their respect for Agron, being surprised that there are still witnesses of this age who have challenged the communist dictatorship, now with their shocking testimonies, as if not to be forgotten by history. /Memorie.al