By Njazi Xh. Nelaj

Part Three

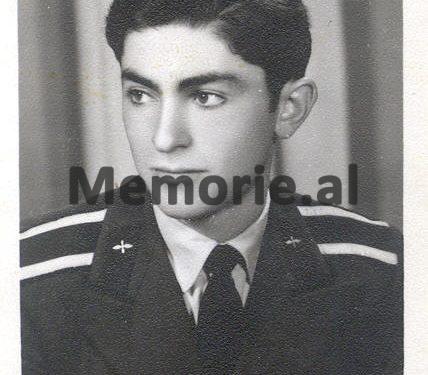

Memorie.al / Impressions and memories from the life of the talented pilot tragic hero, Colonel of Aviation, Niko Selman Hoxha, who lost his life in the line of duty on November 20, 1965, at the military airfield in Rinas, during a combat exercise with the MIG-17F jet, in front of the regiment’s personnel and several military academy cadets. The impressions and memories have been gathered by Niazi Xhevit Nelaj in June – July 2012, in Vlorë, Tirana, Voskopojë, etc., during meetings with people and telephone conversations, reaching as far as distant Boston. Every meeting and conversation with contemporaries and relatives of Niko Hoxha has been reflected in the material with fidelity and authenticity. The monograph reflects only a part of the hero’s life, the part related to aviation and flying, and does not extend to other spheres of the multidimensional life of the man who gave impetus to military and aerial discipline and training. Niko Selman Hoxha, as he was disciplined and extremely correct, was also distinguished by an exemplary lifestyle. He did not live in the barracks and did not eat in the quality mess hall for pilots, but at home, thanks to the dedication and good management of his wife, Jolanda, his regimen lacked nothing. This writing does not include Niko’s family life, nor his care for his sons, Valer and Sasha, who were still young when he passed, but whom he surrounded with much parental love and care while he was alive. Other writings that will follow will surely shed light on those aspects of Niko Hoxha’s life that have remained somewhat in the shadows in this monograph.

Author

Continued from the previous issue

The noble face of the colonel was beautiful, with a sandy complexion. Niko had large, brown eyes. His eyebrows were pronounced but not “unruly.” He had a high forehead and brown hair with a tuft that he preferred to keep under the cap’s brim, tilted to the left. The colonel sported a mustache, perhaps to “mask” his nose. Niko’s mustache, a sandy color, was always well-groomed, clean, and neatly trimmed, adding charm to his kind face. He smoked a lot, and both nostrils were stained yellow from nicotine. Niko Hoxha’s face was lovely when he smiled, and became equally charming when he turned serious. The colonel’s outward appearance expressed his culture and love for the army, order, and discipline, and showed respect for the people he worked with.

I spoke with 85-year-old Bajram Hitaj, who was the pilot of the only Albanian bomber, the IL-28. When I asked him when and how he met Niko Hoxha, Batja (as we used to call him), with his characteristic seriousness said: “Niko Hoxha was born for the military. God had given him all the qualities of a brilliant commander and officer.” I listened to Batja and recalled how we looked at the colonel, in the light of our eyes; we observed and never grew tired of admiring that military portrait, as if it were embroidered by a masterful hand.

Commander Niko often came to see us as we developed our physical training, we young pilots. One day we were practicing on gymnastic apparatus under the guidance of the relevant instructor. We were lined up near the gymnastic bars. It was my turn, and I tried to climb up. I jumped, but couldn’t grab the apparatus. The colonel, as he usually did in such cases, placed his hands on his hips, laughed heartily, and said: “But you, junior, what do you have with this belly of a general?!”

“I was embarrassed, and from that day on, I began to exercise intensively, through special exercises and tools, to reduce my belly. To be honest, without boasting, when I set to work on writing this monograph, I didn’t think it would be so difficult. I took this task lightly, but it turned out otherwise. Now that I’ve ‘entered the water’ and am learning ‘how to swim’, I realize that ‘I have stepped into the sea, standing up’!

I don’t say this to justify myself for the difficulties I encountered along the way, but to emphasize one thing: The qualities and virtues of that ‘superhuman’ man are so numerous and varied that there is no storyteller who can capture them all in a narrative. Recently, in order to learn more about the life and activities of the 39-year-old colonel, who lived a short but ‘peaceful’ life, I met and spoke with many people from various professions, those who were close to him, worked with him, or were companions of the brave commander, Niko Selman Hoxha.

I met with not a few but around 35 people, and they recounted so many things, both spoken and unspoken, that when I began to incorporate them into this story, I was overwhelmed and didn’t know whom to take or whom to leave, as each of the stories has its own value. Earlier in this writing, thinking that I was giving the hero something he deserved, I referred to him as a ‘div’, a title that is fully justified.

However, when I spoke with my friends, 85-year-old Haki Jupasi, a pilot of the first class and a man of great stature, said to me: ‘What do you mean, ‘div’? He was a ‘lion’, for he resembled a lion.’ I didn’t have the courage or the argument to argue against Commander Haki. Pilot Çobo Skënderi, also a first-class pilot and a contemporary of Niko Hoxha and a good connoisseur of him, further added to that illustrious figure, saying: ‘Niko Hoxha could only be compared to a ‘Zgalem’.”

“I had no desire to contradict that, as it struck a chord with me. Çobo is a man of letters and has written about the colonel. He has done well; each of us who knew the commander has an obligation to immortalize his figure, even though writing. For the colonel, you could assign every positive epithet, as he truly deserved it. Niko Hoxha ‘was there for us’ when we needed him the most, and with his demeanor, he became our ‘mother,’ ‘father,’ ‘brother,’ ‘sister,’ and good friend.

His pure and generous heart was so big that it had space for all those who deserved his love. The colonel knew how to adapt to the ages, professions, regions, and levels of people. I wouldn’t be exaggerating if I wrote that the commander, with his kindness and affection, adapted even to the quirks of people, not the whims or shortcomings of some.

Niko Hoxha felt immense joy and happiness when the pilots he commanded flew well and when things went smoothly. Not only because he saw the fruits of his hard work and dedication materialized in those moments, but also due to the broad spirit and pure heart he possessed. He shone with light and became lively and cheerful when things went well. I recall a fresh incident.

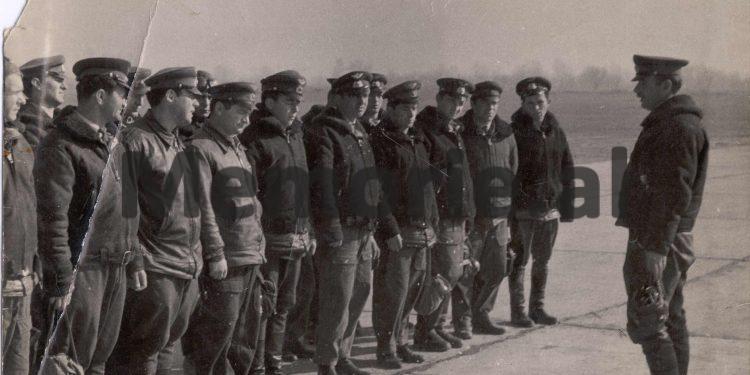

In the autumn of 1963, when the young pilots were flying to obtain their third-class pilot licenses, during one flying day, something unforgettable happened. It was a ‘sine qua non’ condition to fly in a squadron formation (12 aircraft) at an altitude of 10,000 meters above sea level. The first formation took to the air and reached the designated altitude. Twelve white lines parallel and close to each other, beautifully decorated that autumn blue sky.

The colonel got out of the lead aircraft, walked onto the green meadow of the airfield, looked up, and delighted in the mesmerizing view; he laughed and beamed like a child. From time to time, he clapped his hands and feet, pacing around in excitement. Soon, the next squadron took to the air, and I was part of that formation. We would follow the same flight path and complete the same task. At an altitude of 7,000 meters, when I needed to engage the afterburner to give the aircraft’s engine additional power, the mechanism failed to function.”

“The aircraft I was piloting fell behind the planes in front of me, and the formation ‘broke apart.’ We did not reach the designated altitude of 10,000 meters together, but arrived one by one. The colonel, who was observing us from the ground, was very disappointed when he saw the chaos we created, put his hands on his hips as a sign of dissatisfaction, and said: ‘A cracked lip never smiles!’ The passion for flying and love for the air was clearly and genuinely expressed by the commander.

When he wasn’t flying, for reasons beyond his control, no one dared to oppose Niko Hoxha, who, in such cases, would be sulky and brooding. However, his face would brighten and become ‘spring-like’ when he took to the air. The colonel’s motto was: ‘A pilot is one who takes to the air and flies.’ He did not say this as a slogan just to convince his subordinates and colleagues; he put it into practice.

The pilots, especially, would look at Niko Hoxha with admiration. You would see Commander Niko all day, every day, at the airfield, with a radio in hand; ‘hunting’ for weather conditions that didn’t always favor flights. As retired pilot Gëzdar Veipi recalls: ‘We obtained our first-class pilot certificates, thanks to Niko Hoxha’s determination. Every day we awaited the weather at the airfield, with the radio in hand, hoping to catch the ‘good clouds,’ not the ‘aggressive clouds!’

Not only that. Some of the pilots who were flying to obtain their first class in the 1960s had families and lived in Tirana (in the city of Tirana). Niko Hoxha, spending all day at the airfield awaiting suitable conditions for flying, would notice this, especially when conditions were right for flying. To gather pilots together to take their first class (at night, in the clouds), he would drive to each house and collect them.

After giving them a brief preparation, just to remind them of the habits of this kind of flying, he would carry out the flight mission with them. In the group of pilots flying for the first class in 1964 were: Anastas Ngjela, Lulo Musai, Kosta Dede, Gezdar Veipi, Çobo Skënderi, Mahmut Hysa (Uku), Halit Bulku, and Bajazit Jaho. I was returning from Tirana when the last pilot landed that night.”

“With a group of friends, bachelors, we found ourselves at the southern end of the Rinas airfield. We were amazed to see how the sky above the airfield lit up and sparkled from the signal rockets fired by the flight leader, Niko Hoxha. He, out of joy for the pilots in his group who completed the first-class program, discharged all the signal rockets that were around him. The colonel had every reason to be joyful and proud.

With his unwavering determination and commitment, Niko Hoxha had advanced the significant issue of pilot qualification quite a bit. After ‘closing’ the night of flying, the commander gathered the pilots not to give feedback on the development of the flights, as he usually did, but took them to the civil airport’s cafeteria, where he treated them at his own expense. Such was the colonel, with his rare passion and commitment to enhancing the art of piloting.

From the numerous evaluations by the colonel’s friends and contemporaries, I tried to highlight a few that I found most striking and that give us a clearer picture of his qualities. From a conversation I had with veteran Bajram Hitaj, I learned that: ‘As a pilot, Niko was brave and daring. He was a man of honor, tolerant, and kind-hearted. He did not hold grudges and did not know revenge.’ Batja also recounted an incident related to his relationship with the colonel.

‘On one occasion, while we were doing a formation check, I didn’t have my shirt so white; Niko made a remark to me but unknowingly offended me. I countered with the statement: ‘Comrade Major, because of this offense, we are not parting well together!’ That was enough; the formation check broke apart, and people dispersed. The commander went to the office and lit a cigarette. He sent an officer and called me. I went to the office and presented myself formally. The colonel got up and said to me: ‘I can make a self-critique for this before the formation, but you, Bajram Hitaj, with what you’ve done to me, and have given me a great lesson for life, as a military man.’ We left it at that; we went out on the stairs, each lit a cigarette, and the staff saw us reconciled. After that, he never held a grudge against me.’

The colonel loved aviation and flying so much, also for the simple reason that he himself founded, organized, and directed Albanian aviation from its very beginnings. In 1951, Niko Hoxha organized the first squadron of Albanian aviation at the Lapraka airfield, using aircraft leftover from World War II, and recruited and trained pilots from various schools who had returned from Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union.”

“Thanks to Niko Hoxha, the aerial training of the fighter-bomber aviation regiment in ‘Stalin City’ (Kuçovë) was established, organized, and put on the right path in 1954. With the initiative and persistence of the colonel, the first school for pilots was opened in 1958, with two squadrons: one equipped with propeller planes and the other with ‘MIG’-15 jets. Here’s how Bahri Meshau, a former student of this school from Bubës in Përmet, remembers the opening of the first Albanian aviation school:

‘Niko Hoxha was born to be a military leader. As a commander, he valued you as you deserved and never sold you out under any circumstances. Niko often went to see the soldiers in the afternoons, and they would gather around him like bees to flowers. On Sundays, when others took a break, he would spend 2-3 hours with the ready pilots, talking with them. In 1960, when Niko Hoxha was the commander of the regiment in ‘Stalin City,’ he had two squadrons under his command, which were training pilots. One was in Pishporo, and the other in ‘Stalin City’.

The colonel would visit both squadrons, not just to observe but to fly with the instructors and trainees. He would never offend you, even when he found you in the wrong. He would jokingly tell someone: ‘You fool,’ or, ‘you have your pants around your feet.’ He treated the cadets well, like friends. Another veteran pilot, Bardhyl Lubonja, who now lives in the United States, called me from Boston and said:

‘I was a pilot trainee in 1960 in ‘Stalin City,’ and after checking me in the air, Niko Hoxha was convinced that I could fly the airplane solo; he signed off, and I took off on my own for the first time. The commander constantly followed our sports activities. He often came to the Rinas regiment in the afternoons, dressed in a yellow sports suit, and played various games with us young bachelor pilots.’

In Niko Hoxha’s short life as a military commander and pilot, several moments stand out where he appeared as a protagonist and acted as a true leader. Without his initiative, the aviation school would not have reopened after a pause, nor would it have trained pilots. It was precisely with the determination and perseverance of the colonel, combined with his competence and responsibility as a qualified and courageous pilot, that the resumption of flights at the Pishporo airfield was made possible in the summer of 1960, following the air disaster that claimed the life of Cadet Jovan Kacori from Boboshtica.”

“Commander Niko was very pleased when flights with the trainees resumed after the trauma they had experienced, but he was quite disheartened when, on the first day of this resumption, trainee pilot Petraq Qafëzezi from Kolonje, during a training flight in the area, found himself in a difficult position and consequently ejected from the aircraft using the emergency parachute. Following this extraordinary event, which posed significant risks to the pilot’s life (the abandoned aircraft was completely destroyed upon impact with the ground), the Aviation School was closed, and the trainees were sent to continue their aerial training in the Soviet Union. This was a major blow to Albanian aviation, which was still maturing, as well as to the colonel who cared for it deeply.

In 1958, when the colonel was the commander of the aviation regiment in ‘Stalin City,’ a group of the most advanced pilots was sent to the Soviet Union to learn to operate the supersonic aircraft (with two jet engines) equipped with air-to-air guided missiles, the ‘MiG’-19 PM. This aircraft was among the most sophisticated of its time. The group of pilots from Albania who went for specialization had to face and overcome numerous growth challenges with more courage and bravery than their colleagues from other Eastern countries, who were not faced with the same difficulties.

Niko Hoxha was tasked, once again, with bearing a heavy burden. He carefully and responsibly selected the list of pilots who would transition to the new aircraft and had to ensure combat readiness with the pilots who remained in the regiment while working to improve their skills and levels. The colonel personally planned, organized, and directed the aerial training of the remaining pilots, and within the year (when the qualification group of pilots was in the Soviet Union), he brought them to the highest levels of the regiment. In this way, Niko Hoxha, known for his initiative and competence, faced the toughest challenges and overcame them, simultaneously breaks through inhibiting concepts and trends. Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue