By Xhevahir Gradica

Memorie.al / In the Hamallaj sector, a few kilometers from Durrës, for nearly 40 years, the descendants of the noble, patriotic, and national family of the Bajraku of Mërturi, from the Tropoja district, have lived. After enduring all the suffering and contempt imposed by the communist regime to the limits of the unreal, Prelë and Gjon Vatnikaj decided to settle somewhere on a plot of land in the west of Durrës, in Hamallaj. Burned, killed, and persecuted, the Vatnikajs and Mark Tunxh Myftari stopped to recover after those successive tragedies. They needed to make a cool judgment for the boys who were growing up amidst the hatred and disdain of the communist regime.

Prelë Vatnikaj has passed 80 years, and his younger brother Gjon is also approaching that age. On sunny days, they stay on the porch of the house, sometimes sighing and sometimes reminiscing about years, times, and past experiences. Both lean on the stick of old age, but the clarity of remembering events, episodes, names, historical facts, and everything related to the fate of the Bajraktar of Mërturi in the Highlands of the Tropoja district stands out.

Nearby, the women of the house and the daughters-in-law approach with a tray for the cigarettes of the elders and curiously follow the conversation with Prelë and Gjon, as if they were hearing for the first time the sad stories filled with tears, lament, longing, despair, pride, and strength. In this house, but not only there, they now believe that to survive, they cleaned the corn kernels from the horse manure and after washing them, they boiled them to share the kernels equally among the hungry family members in the internment camps in Berat, Tepelenë, and Lushnje.

Here, you might be surprised, and for a moment, think you are listening to a ballad when you learn that Mrika, the falcon mother of Prelë and Gjon, has pulled her hair out to sew her son’s pants, pants that are now in the National Museum. Prelë testifies, among other things, that he witnessed how the bullies of the communist regime, after burying Muharrem Bajraktar’s wife, exhumed her to snatch her golden teeth.

The Bajraku of Mërturi had not reconciled with any regime that did not bring freedom to the country. The men of the clan who held the flag of the region have been killed and mutilated, interned and imprisoned by the Ottoman Empire, Austrian rule, King Zogu’s regime, and the masters of the Enverian communist regime. But they finally survived. The Bajraktar family of Mërturi from Lekbibaj has relocated to the Durrës district, taking with them the memories, pain, and longing.

The Testimony of Prelë Vatnikaj

Mr. Prelë, you are one of the sons of the Bajraktar of Mërturi who survived the communist regime…?

The years have passed and perhaps the memories come somewhat damp. Everything seems to be happening before our eyes, before the eyes of our children, wives, and our late mother. Since the first internment in 1946 until today, many years have truly passed, but nothing can be forgotten. We did not relocate from Kolgecaj; we were forcibly expelled, interned by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha. Our family, as heirs of Mark Tunxh Myftari, Bajraktar of Mërturi, had become enemies of Enver Hoxha’s regime from the very first days when power fell into the hands of the communists.

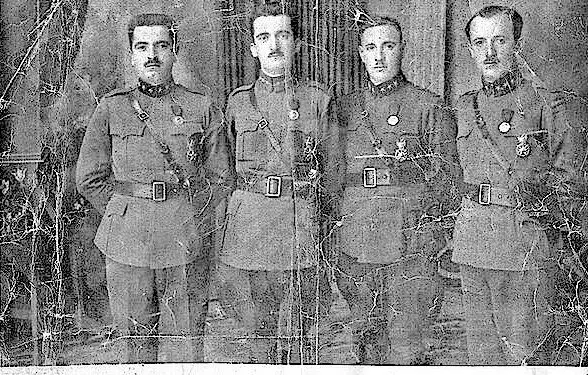

My father and all those who supported Mark Tunxh Myftari were patriots, nationalists. They wanted Albania without communism, free and equal to other Western countries. All the families of the Bajraku in the North, most of whom I had the fortune to know in the internment camps, were patriotic families and never reconciled with communism. They had instilled these beliefs during the time they studied abroad. Marku, my father, graduated from the Military Academy in Rome. There he met captains and officers of the Bajraku of Shoshi, Lumë, Nikaj, Shala, and Shënkoll.

There, my father met Muharrem Bajraktar, whose son we lived with in the internment camps in Tepelenë. It is true that from Mërturi, we took with us the memories, longing, and pains. It does not matter which of them was greater. We left our homeland in the Highlands, burned and destroyed. Not due to a misfortune, but because the mountain committees burned us, because we were patriots and loved our country without communism. No one came to see us off from the village.

Even this time, not because they didn’t care, but because the “mountain committees” of the Communist Party would choke them with their bread. Our tower was burned. They took our livestock. The little property that remained, along with the memories of our ancestors, turned to ashes. That’s how we left. Go ahead and turn your head back, hoping that one day we would return to the homeland of our ancestors and with the hope that we would rebuild the tower.

What was the fate of the members of the Bajraku of Mërturi family after the communist regime came to power?

Even before the regime of Enver Hoxha came to power, ‘Pursuit Forces’ from the Ministry of Interior arrived in our village. It was the winter of 1944. They set our three-story tower on fire. Father, Mark Vatnikaj, along with our older brother, Zef, had gone to the mountains because the ‘Pursuit Forces’ were looking to kill them. Mark had crossed the border several times to save his life. He was sought to be killed by the Turkish ruler, by Zog’s gendarmerie, and by Enver’s communists.

We rarely met with our father and Zef. They stayed mostly in the Nikaj Mountains, in Kakia. They lived by eating chestnut leaves and slept in caves. The shacks were unsafe for their lives. For four consecutive years, they and other patriots from those areas fought against the Pursuit Forces. In 1947, in Lekbibaj, Zef was surrounded by the forces of the communist regime of the time, and during a shootout, he was killed by a shepherd from the village who had joined the Pursuit Forces. He deceived him, tricked him into an ambush, and at the moment Zef tried to escape the ambush, he was shot by the shepherd.

After this event, Mark went deeper into hiding, and our connections were cut off, as we had been interned for more than a year and could not escape from Tepelenë. The communist regime of Enver Hoxha cooperated with the Yugoslav UDB to kill our father. Mark Tunxh Myftari was imprisoned by the Serbs in the prison of Pejë, where he was held until 1952. In that year, UDB agents took him out into the courtyard of the prison and shot him several times with a pistol, taking his life.

In this case, we were also interned. When we were expelled from Mërturi, there were only four members of the Bajraktar family: grandfather Tunxh, who died in internment after five years, our mother, Mrika, I, and my brother, Gjoni. We spent a year in Berat and then in Tepelenë. We suffered like a snake under a stone. The concentration camps cannot be distinguished in terms of the indignities faced by classes of persecuted individuals. For bread, milk, food, all honest Albanians suffered, but we who bore the political stigma also carried humiliation on our shoulders, as the regime worked to dismantle us in various ways.

In Tepelenë, you say that you ate corn after taking it from the livestock dung…?

I am sure that many Albanians believe this, all those who lived under that regime and know what it meant to be interned. We were in Tepelenë. Hunger had exhausted us immensely. Mother Mrika woke up very badly. We had neither bread, nor flour, nor pasta at home. We didn’t even take the trouble to ask for bread because no one would open the door for us, even though there were many honorable families there who suffered from our way of life. With the village men, we would talk piecemeal and more often exchanged smiles from a distance than shook hands.

It was difficult in the initial days of internment when we saw that no one would sit at our table in the café. It hurt our hearts when men and women came out of the store while we entered to buy salt or food. At first, I didn’t understand, but then I realized that all of them were scared, as there were agents of the State Security everywhere. They had placed us to live in some former warehouses, and the windows were half glass and half plastic. I saw my mother pass through another part of the warehouse. There, among the horse dung, she had started to collect corn kernels.

I helped her, and after we washed them with water, we put them in to boil and then shared the kernels equally. Father Marku and brother Zefi ate fodder in the fall to survive, while we in Tepelenë ate corn from the livestock dung. I also remember one day when Gjoni, my little brother, told mother that his clothes were torn. I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw Mother Mrika pulling her hair out and starting to sew pants for him. Those pants are now in the National Museum in Tirana and are a testament to the pride of our family, which never submitted.

In 1994, an Italian came to our house. He was brought by the son of Hasan Dosti, with whom we had become acquainted in internment. The Italian offered us a very nice gift, but neither I nor Gjoni thought we should give it to him. To avoid sending the friend from Italy back empty-handed, we took the scissors and after cutting a piece of the pants, we sent it with him.

To not only endure these sufferings, Gjoni is imprisoned and sentenced to 10 years…?

In 1952, the police came to our house and took Gjon. He was very young, not yet 17 years old. He was accused of speaking against the regime. For the same accusation, others were arrested as well: Kurt Kola, Genc Bajraktari, Fiqiri Dine, Qemal Dema, Haki Alla, all members of interned families. Gjoni was sentenced to 10 years and was only reunited with us in Lushnje.

At the trial, he was only called an enemy, but it was never mentioned that our father had escaped, that we were a family from the Bajraku of Mërturi, that Zefi had been killed by the Pursuit Forces. So the trial was not against Gjon, but against our family. They labeled him as the son of a criminal, even though our father was an officer who fought only against the occupier and to defend himself, and also against the forces of the State Security of Albania. Gjoni served his sentence in Gjirokastër, Burrel, and Shkodër.

In Tepelenë, did you also get to know the family of Muharrem Bajraktari, the Bajraktar of Lumë in Kukës?

Muharrem Bajraktari, as I mentioned earlier, had known my father, Marku, many years before we, the sons of Marku, met in the internment with Muharrem’s son and wife. They (Muharrem and my father, Marku) had graduated from the Military Academy in Rome and were very close.

The Bajraktars met both in our tower in Mërtur and in Kukës, in Muharrem’s palace. We were devout Catholic believers, and religion did not allow us back then to take or give a girl in marriage to a Muslim family. To strengthen their friendship, Marku and Muharrem Bajraktari swore blood and became brothers.

In Tepelenë, we had contact with Genc Bajraktari, Muharrem’s son, as well as with the Bajraktari family, Nazife. I cannot recall which year Nazife passed away, but there were 2-3 of us men at the funeral. After we buried her, someone came and told me that someone was digging at Nazife’s grave. They had exhumed her and broken her jaws with a crowbar and hammer.

All this crime was committed to take her golden teeth. There are witnesses to this unparalleled shame. I had never heard in my life or read about such a massacre! And all of this was done by those who would kill at night and weep during the day. The people of Tepelenë know well who exhumed Nazife Bajraktari to desecrate her corpse.

After Tepelenë, the suffering of the Bajraktar of Mërturi family continued in Lushnje. But there, you and Gjoni began a new life…?

In 1955, we were interned in Lushnje, after 8 years of suffering in Tepelenë. We settled in the Gjazë sector, Savër. It was a farm, and we were saved from hunger since we had bread to eat. The same rules applied the same obligations for us, to report to the police, to obtain permission if we wanted to go to the city, and so on.

I had turned 27, while Gjoni was still young. To be honest, those who commanded us were uneducated, unruly, immoral, and ignorant in the full sense of the word. I had graduated from the “Kosova” Internat in Krumë of Has, a school with great authority in the quality education of students.

There were many boys from Albania and Kosovo there. I remember that the principal at that time was Rifat Spahiu. Fadil Hoxha from Kosovo, one of the well-known Albanian politicians during Tito’s regime, was two years ahead of me, while I was of the same age as Rexhep Demiri, Shyqyri Bulica, etc. After finishing my studies, I was appointed as a legal representative in Lezhë.

At the age of 16, I was a partisan during the Liberation War, and I became a partisan at the urging of my father and uncle Tunxh. The communist regime had documents, but they never wanted to acknowledge this fact. However, only a year after I worked in Lezhë, they dug into my biography, and everything collapsed for me as soon as I left the local command.

Nevertheless, your family began to grow in Lushnje, initially with your marriage and later with Gjoni’s…?

When I got married, Gjoni was serving a sentence as an enemy of the people, and grandfather Tunxh had passed away. I married from the known family of Çun Kola, a proud Bajraku family in Nikaj. At my wedding, it was just me and mother Mrika. The bride, Buba, was brought home from Nikaj by her sister. Nobody knew about this connection.

Buba’s father was in the mountains and remained more often in hiding for the same reasons as Marku and Zefi. The girls had set out for Lushnje, on their father’s orders. When my future bride entered the house, she was dressed in girl’s clothes. We had no candies, no sugar, and no sweets at home. Mother went out and returned some time later with some bridal clothes, which she gave to the new bride.

We left the house, and after getting onto a cart, we traveled the village road. From the marriage to the girl from Nikaj, we had 6 boys and 1 girl. All the boys were educated after the democracy in Albania. Marku graduated from Economics; Sokoli graduated from the Academy of Order; Zefi, Viktori, and Tunxh graduated from law school, and Gjergji continued working in the state police. My brother Gjoni married the daughter of the family of Lulash Gjeloshit, Bajraktar of Shoshi. This patriotic family, strong and well-known in those parts, has a special history.

The tower of the Bajraktar of Nikaj was surrounded by the Pursuit Forces seeking to capture the old man, Lulash Gjeloshi, alive. To protect the honor of the Bajrak, the boys, nephews, and men of Nikaj stepped forward alongside Lulashi. For a week, the tower remained surrounded. In the conflict, 13 patriots of the Bajrak of Nikaj were killed, while the Pursuit Forces lost 84 men. Our families have maintained strong ties throughout life with honorable clans and towers that have sacrificed for the education of sons and daughters, for the honor of the country, and for the ideals of freedom.

More than 25 years of internment did not weaken us. Neither the years in prison nor the provocations of the communist regime defeated us. We have sought to preserve and educate these qualities in our descendants. For us, the most cherished principles are patriotism and nobility. We have valued these and only based on this principle do we assess the values of individuals and society.

Now times have changed. Do you intend to return to the homes of your ancestors in Mërtur and Lekbibaj?

Our internment ended in 1970. In Lushnje, we had a farm director, Sulejman Gallai, with whom both Gjoni and I had acquaintances and had met several times for family economic work. At the time we were released, Sula had become the director of the Sukth farm. I met him, and he advised me not to be overwhelmed by nostalgia to see our homeland as soon as possible.

Knowing our temperament as mountain people, it seems he was afraid that Gjoni and I would make some hasty decision. Sulejman Gallai was taking a risk as he tried to convince us to find a place somewhere in the plains. We were sure he had created an understanding of our past and of the character of our family.

We consulted with the women and boys and decided to settle in Hamallaj. I have been in my tower, the tower where I was born, which connects me to many memories. Today the tower has been rebuilt by the cousins who are there. In recent years, we go back and forth, but living in those very remote areas of the Tropoja Mountains has become exceedingly difficult. We feel proud to belong to those homes, as we have sacrificed a life to preserve everything we learned in those towers./Memorie.al