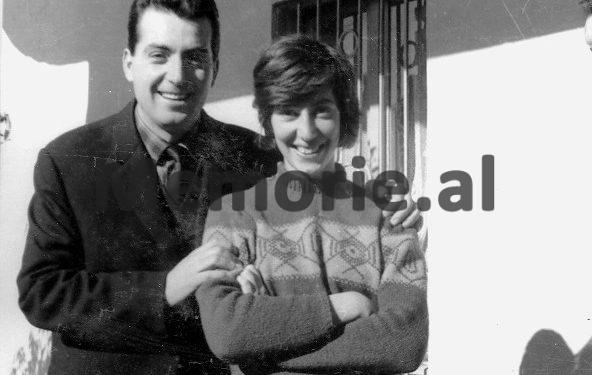

Memorie.al / It is strange how life takes a downward turn. While you’re well and good, in the blink of an eye, you find yourself in internment. Moreover, coming to understand that you have only known the facade of life, where the reality beyond the “Block” spoke the language of poverty and misery. But alas, ironically, you might find such ‘surprises’ that the Party ensured were not lacking, like many absurdities of that time. Therefore, the fate of Kozeta Mamaqi, the daughter of Dashnor Mamaqi, former editor-in-chief of the newspaper “Zëri i Popullit” and Secretary of the Tirana Party, who suddenly became an “enemy,” could hardly escape the scrutiny of the regime. Nevertheless, before the “dark days” of internment came, Kozeta’s life, who followed a journalism course, was filled with all the good things, not at all fitting for a character like Kozeta, reminiscent of Hugo’s protagonist.

Perhaps the similarities would come years later, just when you least expect it. A childhood filled with toys and childlike curiosities. Further, an adolescence without complications. It is easy for her to talk about those years, but even the expulsion to Selenica in Vlorë and the divorce did not take away her humor at a time when there was little to laugh about. Despite the numerous sufferings, she claims she found the strength to move forward with her head held high.

As a journalist, then a “shovel technician,” a teacher for a year and again a journalist, Kozeta expresses that she enjoyed all three professions. In fact, she defines her relationship with the shovel as one of love, as the only tool that eased her existence. Beyond the hardships, the daughter of Dashnor Mamaqi recounts extensively about her close relationship with her father, the conversations they shared, the correspondence from her time in Moscow, and all the way to the cold prison cells…!

Ms. Kozeta, it is said that childhood is one of the most important periods of life and particularly affects the formation of a person’s character. What do you remember about it?

There was a time when religious celebrations were allowed. We would go to church to see the girls in long dresses being baptized, and then they would kiss all those icons, as if we had gone to some extraordinary place. Meanwhile, at the mosque, we would just get our shoes mixed up. Even though our means were limited, it was a childhood filled with games.

However, I was also involved in various activities, such as piano, recitals, and various sports, unknowingly honing my skills for the difficult years that would come later. I studied piano at the Pioneer House with Mrs. Baçe, who was a very beautiful woman. She was different from other women. Whenever we had a break, she would take out a mirror and put on makeup, which was rare at the time. I still remember her model, which was so modern for that period.

What was your relationship like with your father, Dashnor Mamaqi, during those years?

Until I was six years old, I had a closer bond with my grandmother, because my father at that time went to study in the Soviet Union. I felt his absence very much. He communicated through letters that contained lines specifically for each of us children, a practice he maintained even when he was imprisoned. I idolized him, as I always saw him with a book in his hand. He was serious, unlike my mother, who had a joyful and cheerful nature.

Did he nurture your love for books?

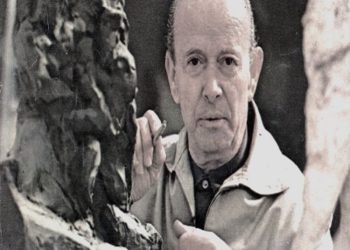

My father wanted us to read and to have culture. He had a very large library, as whenever he returned from the Soviet Union, he brought back more books than material goods. However, he inherited this culture from his father, who had five books in the National Library, and he would go all over Albania distributing them. The newspaper “Drita” of that time wrote about him, but I did not know him, as he passed away at a young age.

What impressed me about these publications was the sensitivity. At the end of the books, the name of anyone who contributed with gold pieces was written. The dedication at the beginning was made to King Ahmet Zogu. My grandfather also had a café named after Omar Khayyam, where the men of Përmet would gather and discuss among themselves. My father published a volume of stories and later entered politics. Later on, it was I who followed the writing tradition.

Your father worked as the editor-in-chief of the newspaper “Zëri i Popullit,” and later as Secretary of the Party Committee of the Tirana district, a time when material goods increased significantly. What was life like in the former “Block”?

Life in the “Block,” in my opinion, was the same as beyond it. There weren’t many differences from other people. To some extent, they resembled the living style. It was a different matter for the members of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the PPSH. We didn’t have the conditions they did; however, there was a special shop where food and industrial goods could be purchased. Unlike ordinary people, we had a housekeeper. But my grandmother and mother didn’t just sit idle. They worked all day, setting a good example for me.

Did you feel privileged compared to your friends?

No, because my friends at school were just the same, they ate bread with butter and cheese, just like I did, and did everything I did. The only place where the disparity in living standards was felt was the beach. But even there, I would go out of the hermetic “Block” to enjoy time with my friends.

At the beach, the difference was felt because you had a sailor available to teach you how to swim, a doctor who checked the water temperature, and if the water was cold, they wouldn’t let you in. We had ballet teachers, children’s cinema in the morning, and a schedule for adults that we would sneak into. That was where differences were noticeable; while in Tirana, I didn’t feel any privileges. I didn’t do anything less or more than the others.

You mentioned that you had your father as a role model. How did your relationship evolve over the years? Was he authoritative?

No, on the contrary, he was very calm and sweet. He would affectionately call me “daddy’s little treasure.” Later on, everyone started calling me Kozi, and he would call me Xeti. When it came time to convince me about my future, he would present a thousand arguments. Regarding the choice of university, I consulted him because if it were up to me, I would have chosen medicine. He encouraged me to study language and literature. Afterwards, I graduated and completed a two-year course in Journalism.

Did he consult you regarding work-related issues?

He never brought work problems home, except for one time when he chose to confide in me about a book by Bilal Xhaferri. He was very affected. He told me that a young man had given him a book about Skanderbeg, a book that, according to him, was one of the most beautiful he had ever read. With his eyes lost in thought during his recounting, he continued to tell me that the boy had an iron will and laid the roads, and whenever he managed to take a day off, he would go place to place to gather folklore and material about Skanderbeg.

He was left with regret because he foresaw that book would never be published. And so it happened. His regret was so immense that the memory of his black fingers from the asphalt would not leave him for many years. That was the first and last time he confided in me openly. Afterwards, our life took a downward turn.

How did you discover the reality beyond the “Block”?

I had been working as a journalist for several years and had traveled to various places. But only when I was interned did I realize that everything I knew and had seen was merely a facade, as poverty was extreme. I couldn’t understand from the reports of that time, which were predetermined by the Party Committee. At that time, I also published my own volume of stories and sketches, of course within the frameworks of socialist realism, as indoctrination was extraordinary. I had not known life, and it was only by touching it closely that I grasped reality.

How do you remember the moments when you received the news that your family had been declared “enemies of the people”?

At the same time that my father was arrested and imprisoned, I received a notice that I had to appear at the People’s Council of the neighborhood. There, I met with my father’s friend, journalist Jusuf Alibali. He closed my eyes, and I understood that everything was over. When I went there, they told me that I would be leaving Tirana the next day. At that time, I had both of my children.

They took me away that day in a large truck, the neighborhood loaded up our belongings. Later, much of our stuff was seized in Selenicë. I remember that I made a couple of tricks to save the library. The bags of books that were supposed to be seized, I filled with didactic books, while I saved the important ones.

Where did that truck take you?

After we were taken on a tour around Tirana to see the “enemies” of the people, they covered the truck, without us knowing where we would go. I even remember that on that day, my little boy had a temperature of 39 and a half degrees, and they barely took him into the cabin with me. Meanwhile, I was sitting on top of the truck with my older son, and no more than 40 points away from me was a policeman with an automatic weapon.

They stopped us in front of the house, where my grandmother, mother, brother, and sister were waiting. They had arrived a few months before me and had settled into the house assigned to us. That is when I learned I was in Selenicë, Vlorë. We were in extremely difficult moments, but at least I had my family nearby. I remember there was no place to leave our belongings. We sold some to survive; the rest rotted in the yard.

After a life filled with all the good things, how did you cope with your relocation to Selenicë? How hard was it to accept that all the privileges were now just part of the past?

At first, it was hard to believe. I held such high hopes that our internment and my father’s imprisonment seemed unjust. I wasn’t yet clear about what had happened to me. I didn’t start working because my right to my profession had been denied. When all my efforts and dreams came to an end within a month, I returned “with my feet on the ground” and began working wherever they sent me. I had no other option but to adapt. And that’s what I did.

What did you do?

They gave me a shovel, a belt, and a hoe. We, the declasse, were left with the heaviest jobs in agriculture. On my first day at work, I went in a pair of ordered shoes with woolen cuffs, which got stuck in the mud. The next day, I wore rubber boots, while my feet got soaked every day from the humidity. Not to mention the patched pants that my mother had become a specialist at making. These were long and very difficult years, but I managed to endure thanks to my strength and hope. Today I wonder where I found that strength.

Even though I have faced many illnesses, I still do not feel weak. However, there were moments I remember nostalgically even amidst all those exhaustion and mandatory calls. Or better yet, I managed to be optimistic even where there was no place for it. I was the first to go to work and met my daily quota. Moreover, I specialized as a “shovel technician.” I fell in love with my shovel so much that even when we finished working, I didn’t hide it like other workers did in the fields, but always kept it on my shoulder. That simple-looking tool made my existence easier.

How did the locals behave towards you?

At first, they were wild. They would provoke us because we were different from them, drowning in poverty and ignorance. They would prejudge us in every detail, and although my family and I were morally downcast, we came from a different mentality, from the capital, amidst all the good things. This was precisely what they did not look upon favorably. But when we arrived in their shadow, wearing patched pants and eating beans like them, it seemed they forgot us.

Whether they wanted to or not, they approached us, the “enemies,” but of course with reservations. I remember one morning we had run out of bread at home, and I had nothing to take with me to work. I went to the workers’ canteen at the mine, where other people were waiting in front of me. When it was my turn, the seller told me that the bread was finished, even though there was still some…!

What was the hardest moment you remember during those years of internment?

Besides being interned, the Party ordered my husband to divorce me. After all, anyone in his place would have acted the same. But this was not the greatest misfortune; that came later. I went through six court sessions to settle the custody of the children. At first, they gave me both boys; then the decision of the Vlorë Court ruled that they would live with their father.

The worst moment in my life was when they came to take the boys by force, and I fainted. It was the only time the whole of Selenicë cried in their homes. This was the hardest part—taking a child from their mother. But even the separations were decided by the Party. Later, I found out that my ex-husband had cried publicly after he requested the divorce and won custody of the children.

Did you maintain contact with your father in prison? Had he fallen morally, as expressed in the letters he wrote to you?

He spent two years in custody under the infamous investigator, but even after the torture, he did not sign the charges that were brought against him. He was sentenced for friendship with Beqir Balluku and his group. They placed him in the “Cultural Group,” although he had no connection whatsoever. Twice a month, he would write us letters, always emphasizing that he had done no wrong.

“Keep your head up,” he always wrote, without realizing that those letters were being monitored. Even in visits, he would repeat this advice. He wouldn’t go further, but would assure us that he hadn’t touched the Party’s hair. Nevertheless, over time, even this protest of his faded away, and the conversations focused more on family. I keep all the letters.

How many years did you stay in internment?

A full 11 years. I left at 29 years old and left after 40. There, I lost the most beautiful years of my life.

Where did you live after Selenicë?

I moved to Shijak, where I worked in sewing from 1987 until 1990. Then I was able to take my right to practice and worked for a year as a language and literature teacher in the village of Luz i Vogël in Kavajë. Those were some of the most nostalgic years of my life. Even though I would get up at 4 in the morning to catch the only bus, I was happy. I was always kind and loving to my students, so much so that some of them still remember me. While I was working at school, I received the news that they had written about my father in “Zëri i Popullit,” somewhat rehabilitating his image.

It was my university friend, Spiro Dede, who had once been a journalist at “Zëri i Popullit” and who knew my father closely, who wrote that article. It was one of the most touching days, where my whole life passed before my eyes, so much so that I missed the bus and lost track of time. I had a hard time, but wherever I ended up, I did not bow down but lived my life as it came./Memorie.al