By Adelina Gina

The first part

-“I cried for you like dead, I waited for you like alive”-

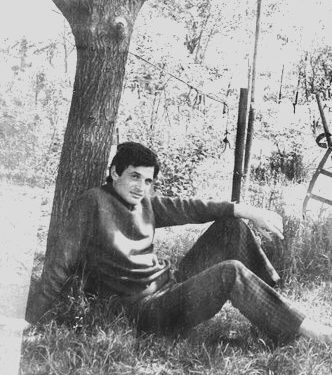

Memorie.al / Shpëtim Gina, graduated in Journalism at the University of Tirana in 1974, playwright, screenwriter and librettist, at the beginning of the 70s, thanks to his extraordinary talent, with his work, works and creativity, “shocked” the artistic institutions of Tirana, such as; The People’s Theatre, the Opera and Ballet Theatre, the High Institute of Arts and the Albanian Radio-Television. He was one of the most sought-after chiefs and senior leaders of these institutions, where in the period 1971-1974, he left his mark, having collaborated closely with some of the most famous names of that time, such as: Mihallaq Luarasi, Kujtim Spahivogli, Pirro Mani, Mario Ashiku, Zhani Ciko, Nikolla Zoraqi and director Mevlan Shanaj and operator Pali Kuke. But the traces he left in these cultural and artistic institutions were unfortunately lost or dissolved in the dust of time and the official silence of the communist regime?! After in August of 1974, Shpëtim Gina, lost her life in still unexplained circumstances, drowning in two feet of water, in the river Drojë of Mamurras, (where she was conducting the military choir together with other students), two days before , he had put a lightning bolt on the Chief of the General Staff of the Army! Was it really an accidental death, or was Shpëtim Gina eliminated by the State Security?! A question that has not yet received an answer! His sister, Adelina Gina, graduated in journalism in the late 60s, in a book of hers entitled; ‘Where did you take Salvation’, published in the USA where she lives with her family after the 90s, tries to reveal the big truth about her brother!

Twenty-seven years have passed since then. I worked as a journalist, while he continued his studies in Journalism. There was a three year gap between us. Our family lived in a small provincial town, which we loved very much. It was a city of workers with lots of greenery, with narrow streets, with people who knew each other well. We lived in a big house, together with another family. We were separated by a wide corridor, which we often turned into a playground. It was a one-story house with a pergola on the porch. There were many gardens near it. Our life was interesting. There were many children and places where we could play. Cultivated fields and vineyards stretched to the border of the main road. Below it continued the city with two large greenhouse pits, still uncovered.

In the winter, when it was cold, we would go to the greenhouse pits and slide on the ice sheet. It was one of the bravery of our neighborhood, because there were times when the ice broke and the greenhouse was swallowed. I remember how a friend of mine screamed when the ice broke. They barely got him out. He was black and naked. Behind the city was the river, but we didn’t go there. It was deep and haunting. Our parents wouldn’t let us. In this neighborhood, children played outside until late at night.

We, the youngest, were told scary events with dead people. I remember the story of the father of one of our friends. On a hot summer night, when we were all sitting and telling stories, a man dressed in a white suit approached and asked about his daughter. He presented himself as the father who had died and risen from the grave for him. We were all shocked, we ran home. The man in white quietly left.

I remember another event; I must have been ten years old. I had finished reading “Anna Karenina” when I wrote a letter and placed it on the pergola above the porch. Not even two hours passed, I heard that my neighbor, we were the same age, was crying loudly. From the side of her window, there was a plum tree, I climbed into it and saw her brother beating her. I went down and I didn’t know where to go because of shame. Do you know what happened? I had addressed that letter to her, with these words: “Let’s talk about matters of love.”

So, although written by a child’s hand, it constituted a crime. But why had I written that letter? Even today I don’t know how to explain it! After a year we changed houses and this one was right next to the street, the voices of which could be heard until late at night. This is the period that we got closer to each other, because we didn’t have children of the same age there. The brother worked and fenced the garden in front of the house.

We planted a lot of roses. We made a real flower garden. Every time May comes around, I look for that sweet, slightly chilly, sleepy scent of my garden. I haven’t found it in a while. At this time, we became a sister. Before my mother gave birth to Mira, I used to say: “O God, give me a boy, so that I can be the only girl”

Salvation said: “O Lord, make me a daughter, so that I may be an only son.” When Mira was born, I cried a lot and looked at Salvation with anger. But he didn’t look very happy either. “Huh, were you glad you were an only boy?”, I said. “No, he said, I’m upset that you cried so much.” We agreed. He told me that Mira was very small and dry. I remember, they said it is one and a half kilograms.

Before mother bathed him, we used to go to see him. He had heard his mother say that she is so weak that her skin sticks to the sheets. He would pull me and say: “Come and hear how Mira’s skin crackles.” Mira was thin, but her eyes were like fireflies, she had blue, beautiful eyes. “His eyes are beautiful,” I said. “Yes, he claimed, but only the eyes, yes”. Mira slowly gained weight, her hair became yellow curls. He had a habit, and when he grew up, of opening and closing the door. We called them “Laper”. I don’t even know today who this Laper was, but surely a man who opened and closed the door.

Black-haired, green-eyed, white, with a Greek nose and thick lips, Salvation was charming. I was a healthy child, while he was delicate, thin and tall. He was not wise, but he was very restrained. In the old house, we had a Jewish neighbor, Sabiken. There were eight people in the family and they had nine cats. Salvation played with them, fed them, and since then the epithet remained; “Sabika’s cat”. We had some land behind the house. He worked and planted it. At the end of it, he had built a coop for chickens and cages for rabbits. He fed them himself, cleaned them himself.

When we slaughtered any chicken, he didn’t eat, he was friends with them. Our neighbor was an officer who worked at the airfield. The small town had an airfield. One day the soldiers unloaded sacks of cement and building materials into the neighbor’s yard. They worked for two or three days and built some stairs that were needed to go down to the bach. Spetimi watched attentively how the Ustallar soldiers acted. He asked the neighbor for materials. “I want to do the same as you”.

The neighbor was an elderly man. “Okay,” he said, “but you’re small and you’re not and usta.” “I know how to do it, said Shpetimi, give me some materials”. “Yes,” said the neighbor. – With a condition. I will bring all the necessary materials, but if you make a ladder, I will slaughter that black chicken of mine and drink brandy with you; otherwise, we will slaughter your big chicken. Agreed”?! And so it was. The soldiers brought all the materials.

The rescue worked for days. I had an apprentice. He was very strict. What have I removed those days? Finally, the stairs ended. Maybe they weren’t like the neighbor’s, but they were real stairs. The neighbor slaughtered the black chicken and drank brandy, sitting on the stairs of the Rescue. Our city was young compared to other cities. One could not speak of natives, that is, people born there generation after generation.

All of them, in some way, came from other cities. This mixture gave a wider breath to the city. There was an oil refinery, a mechanical plant, an institute that dealt with oil studies and research; there were a few wells left that produced some oil. There was a layer of intellectuals who worked in these centers. At the same time there were technicians, officers, aviators. People were art lovers. Often on simple podiums, concerts were given. I remember one such night. The rescue, dressed in blue overalls, sang some humorous songs.

The aviators clapped and shouted: “Bravo”!, “And another”! This is how he appeared for the first time as an artist. The mother was very happy. She herself sang beautifully, she had a good voice. He liked to dress up and play, to dance; he had a sense of humor. Father was a sensitive type, very concerned about his health. Later, Salvation would say of him: “It is looking for a disease.” On one of these days, speaking with a smile, Shpetimi had a sense of humor, his lip went crooked. The mother took him to the doctor. It was found that he had experienced facial paralysis. It was winter and he stayed at home.

At that time, the mother brought home a Cham woman. She was muttering something, shaking the broom and spitting. Shpetimi couldn’t stand it and said to him: “Enough of spitting on me”! The mother stepped on his lip, the chama continued to drink. Then they gave him a bottle of cloudy water to drink. “Drink! – said the mother, – “Drink” , she pleaded. “Yes, it’s cloudy,” he insisted. He closed his eyes and drank it.

In these years, we also met another brother, Petrit. Life for the mother became more difficult. She worked as a first grade, primary school teacher. She was very passionate about working with children, while her father was the director of a school where secondary cadres were trained for oil.

He was honest as a person. Someone brought home some fruit and a turkey; they were the ones who fixed their people in this school. They escaped from the countryside, and took jobs in the city. Salvation, Mira and I were very happy. The three of us shared the fruits, it was a dance. Mother liked the turkey. It was big and well fed. “Don’t get too excited,” she said. We didn’t understand. When the father came, she told him how nice it was, the father laughed. “They do this to me. They have no bread to eat.” He snatched the rooster and managed to return it to his master. We were bored. Mira said: “If only we had eaten the turkey too.”

Father often told us about his father, our grandfather, who had been a judge. It was the time of King Zog, a murder was committed in the city of Lushnje. Someone was suspected. The judge sent the gendarmes to do the weapons expertise. The man, whose weapons were searched, was arrested. He claimed that he was pushed into this murder by the Minister of Justice. The king sent the court judge to Lushnje. He declared to the King that the judge of Lushnja does not give up and wants the Minister of Justice as a defendant in the trial. The king ordered that within 24 hours, the judge of Lushnja be transferred to Përmet. The case was closed. My uncle, during the war against the fascists, became a partisan. Grandfather’s house was the base of the War.

The grandmother had a vest, a souvenir from a partisan. My father was anti-fascist, but he did not take up arms. “I couldn’t do partisanship,” he said. “I can’t sleep all day, without a bed, and I don’t eat anything.” “Yes, you have a revolver,” Shpetimi told him. In a suitcase, the father carried a “Beret”, without cartridges. He had taken them, the cartridges, to the office. “My brother gave it to me, I didn’t shoot it.” After the war, my uncle got a post in the party, but he didn’t know how to keep it, as his grandmother used to say. He was criticized for softening the class war that he was sorry that the properties were being taken, until one day he was put in prison. Even the great uncle and the middle uncle do some jail time.

When I was twelve years old, I went with my grandmother to the Tirana prison to see my middle uncle, the one who cursed the government. I was carrying the bags of food. We went up to the second floor, because there was the meeting room. At that time, some yellow, badly dressed men gathered in a corridor with bars. They looked at me like I was the eighth wonder of the world. I couldn’t meet my uncle, because I didn’t have a passport, I had to be sixteen years old. Only the grandmother met him. She always cursed that the money went to prisons. “Only your father, he hasn’t caused me any trouble”. Maybe that’s why he was worried about his head.

I was attending high school at that time. Our city was all green, with paved roads. Often from these streets, a charming young man, with slightly curly light brown hair, wearing tight pants and a scarf tied like the Republicans, wandered. He was nineteen years old. High school girls liked him. He looked like one of the heroes of literature. In the morning I was rushing to school, the boy with the scarf and one of my cousins appeared in front of me. “Let me meet Manny,” he said. The boy in the scarf smiled sweetly at me and held out his hand. The cousin continued: “We have ours. We will come from you in the afternoon. This is the daughter of the one that your mother wrote in the letter.”

I broke up with them because my lesson was about to start. I now had a cousin who liked friends. I didn’t even tell my best friend about this incident, I was waiting for him to come home. I told my parents and urged my mother to lay those embroidered covers. I went to pieces to make the room look as good as possible. He, who looked so scared and confused on the street, came as if he had known us for a long time. That night, the mother had them both over for dinner.

I was very happy. I would surprise my friends tomorrow. They would ask me to introduce them to him. Mani had graduated from the Polytechnic and was working as a designer at the Mechanical Plant. At the big break, I still hadn’t started telling about it. The republican man approached me and grabbed my head. I was in a circle with friends. All the barbell. I left badly. “This is my cousin, found now,” I uttered in a low voice. He burst out laughing.

“Here’s the rod,” he said. This was his favorite expression. He often came to us. My brother and I started loving it. He always had his hands full. He liked to cheer us up. In the spring, he left for a couple of months and sent us a letter, what I remember is that it talked about almond flowers. There were artistic clues. At this time, Salvation again experienced facial paralysis. The doctors decided that he should be hospitalized. Up on the hill is a beautifully built one-story building from the time of Italy, they even built a church inside it. The rooms were double.

We took the rescue to the hospital, mother, Mani and me. Shpetimi lay on a bed, Mani and I sat on the empty bed, mother was arranging the spoils. “I came to the hospital, said Shpetimi. You will go home, I will stay here alone.” “You are sick, you will stay for a while,” said the mother. “I can’t stay alone, I’ll be back with you,” he continued. “What if you stay with me too?”, said Mani. “But he is not sick”, said the mother.

“Hospitals are not just for the sick,” Shpetimi joked. “You are right, this matter will be resolved”, Mani said seriously. I don’t know how he fixed it, but after two days, he was admitted as a patient in the room with Shpetim. Mani was a nice guy and apparently he was after the avaz, Shpetimi was happy. Every time we went to see them, now we had two sick people. They told how Mani poured the medicine the nurse gave him in the bathroom and how Mani talked to the doctor about his illness.

Rescue enjoyed this adventure, which lasted two weeks. In the meantime, he is engaged in painting. There are several landscapes and two portraits of Mani, with the caption; “Mani before the doctor’s visit and Mani prepares for surgery”. From these works and some others later, you cannot judge him as a painter, but the way he pours the colors, makes you think that he is a born artist. When he left the hospital, he became interested in books that talked about the lives of painters.

His father laughingly asked him if he would continue to play music. Salvation had a beautiful voice and at this time and throughout high school, he will sing as a soloist. “Yes, he said, I will become a singer.” In between, he attended a course to learn the oboe. He was very passionate about this gadget. The mother saw this work with concern. She thought that since she was a spirit tool, she could influence it for bad. He had already had two facial paralyses, one eye was a little smaller than the other, and his lip when he laughed went a little sideways. After some time she begged the oboe teacher to stop her lessons.

“He is talented, he will become a musician, he has a great ear for music, and he said, I can’t send him away, but we can make him learn another instrument.” So he started playing jazz. Music will accompany him until the end of the third year. In the fourth year, he begins to write poetry. In this city, heating and cooking was done with gas. In addition to the stove in the kitchen, there was also a heating stove in the bathroom, tall to the ceiling. Being small, the bathroom heated up quickly. There Shpetimi had put a small table and was writing. “It’s the best place for ideas to come,” he used to say. The only person who could go in there when he was working was Mira.

She would take a small stool and sit next to him. He often, to cover the weakness he had for her, said: “It cries even when there is no water tap. It is very soft.” That September, I was going into my last year, Salvation would start my first year, in the same branch where I was studying. In the meantime, a serious event had occurred; the mother was hit by a cerebral embolism, which took her left hand and leg.

My father and mother did not want me to stop my studies. Mira left the day gymnasium and continued the night school, so she served her mother while her father was at work. The father, in addition to the problems at home with the sick mother, also had to face economic problems. I had a scholarship, but for Salvation, my father had to pay.

September evenings are beautiful in Tirana, the streets are full of students, there is life, you can feel a special aroma. Me and Mita, my close friend, we lived together in a room, we were coming down from “Student City”. As always, Mira was tastefully dressed. At the “Partizani” cinema, we met Shpteim, he seemed confused. “He must have messed up the road,” Mira told me slowly. “What are you doing here?” she told him. “I’m getting to know the capital,” he replied. “Come with us”! Mira pulled him by the arm.

We sat at “Bar Sahati”. We ordered steaks, salad and beer. Mira began to tell the story of the summer. At the corner of “Ruga e Barricadave”, there used to be an old shop that was inconspicuous, it was small, and it carried wine. We bought wine there, and since Mita’s mother sent us from Pogradec, we often put apples and cabbage in her room with wine on Saturdays. Every time we went to buy wine, we met one of our lecturers near the store. One Saturday, when we went to the store, we did not see the lecturer. “We survived, I told Mita, we will drink the wine without him tonight”, in the meantime we heard:

“Good evening girls”! We turned our heads, it was him. He must have heard us. Shpetimi was laughing, he felt good with us. Your hands are beautiful and your nails are well kept, said Shpetimi, then you also like a bit of “aristocracy”, he added. “Yes, she said you have keen eyes and are so delicate.” And crossed his hands on the table. He spent the first year at the Faculty of Philology, while in the second year; he asked to switch to journalism. They asked him to enter the competition. “Okay, – he said. – Those, with whom I will compete, are amateurs. I am a professional. It is not good for them, but neither for me. You have not heard of me”?!

So he entered only with the recommendation of a well-known writer, who at the time he had met him, was working as a convict in Berat. This was Fatmir Gjata. This year Shpëtimi worked and prepared the volume for publication; “White Waves”. I remember a winter evening. Mani had come to Tirana to meet us. Now he was working in Laç. He took me from the dormitory and we went to the building where Shpetimi lived. At her door, a friend of the Salvation told us that my brother had not eaten all day that he was writing something.

That Salvation could sit on the typewriter for twelve hours straight, I knew, but that he could go without eating, I never thought about it. He said: “I’m always hungry. I see a child eating an apple, then I go to buy an apple, later another one is eating an ice cream, then I eat an ice cream.” We found him working on a typewriter. “Leave work, said Mani, we’ll go eat dinner, but first, so you don’t die on the way, take these pies”!

He opened the bag and took out eleven pieces. Salvation laughed uproariously. We took a taxi. The city of Student is on the hill, below lies the capital. The dim neon lights on the street, how they created a kind of intimacy and rest between us and the street. Suddenly, in this calm, he said: “One day I will become a great man.” Mani laughed. A shiver went through my body. In the semi-darkness, his eyes flashed, his lips pursed.

That year I finished the drama I titled “She, He and She” and which was later published under the name; “Someone came.” The drama was staged by the troupe of the Higher Institute of Arts. Final year students defended their degree with this drama. The play was banned as a modernist work. For two days in a row, the theater hall was full; a forbidden piece of life was attached to the stage, a young man who dared to dream of another life, who hoped. The frames of socialist realism were broken. Her life was short. At that time, I started working as a journalist. My friends advised me to leave it at that, because it could ruin my job at the newspaper.

One night, when we were returning from a concert, Shpetimi said to me:

“Better with a banned drama than one that comes on night after night and gets stale. You’re more interesting that way. See how people turned their heads at you?! They were talking about you. A young girl with a drama that surprises the audience. They still haven’t come to their senses, what you wanted to tell them, they don’t know. You remember that night. They froze, they didn’t know what to do, then suddenly they understood and applauded, they didn’t leave. The whole hall was with you. I like to write plays. When you write a play, what about me, who is better than you? Listen, how many pages did your play have?” /Memorie.al

The next issue follows

![“They have given her [the permission], but if possible, they should revoke it, as I believe it shouldn’t have been granted. I don’t know what she’s up to now…” / Enver Hoxha’s letter uncovered regarding a martyr’s mother seeking to visit Turkey.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Dok-1-350x250.jpg)