Dashnor Kaloçi

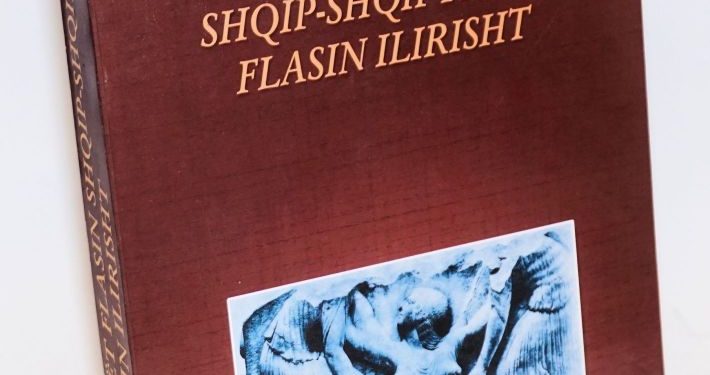

Memorie.al/Somewhere from September 2002, in one of the halls of the National Museum in Tirana was promoted the book “Illyrians speak Albanian-Albanians speak Illyrian” by the scholar Preloc Margilaj from the Albanian territory of Triesi, Montenegro. The promotion, organized by the National Museum, was attended by many intellectuals, researchers, historians and academics, as well as guests from the Albanians of Montenegro and the United States of America. There were also the President of the Academy of Sciences of that time, Prof. Dr. Ylli Popa, Prof. Dr. Luan Malltezi, Prof. Dr. Dhimitër Pilika, Prof. Dr. Koli Xoxi, historian and researcher Sherif Delvina, (“Teacher of the People”), Prof. Dr. Ylli Vejsiu, Prof. Muzafer Xhahiu, Prof. Nikoll Margilaj et al. From the respective papers that were held, Margiljat’s book was considered an encyclopedic work of considerable value. Also, at that time that book was promoted in the birthplace of the author, in Tuz, where referred to the famous scholars and historians: Sherif Delvina, Pjetër Ivezaj, Gani Demiri (Ratkoceri) Mark Camaj, Skënder Skopje, Dr. Prof. Gëzim Boçari etc. In order to have a more complete knowledge about what this work of Preloc Margilaj deals with, which at that time was received with great interest by the academic circles, we turned to one of the most renowned specialists in this field, Prof. Dr. Moikom Zeqos, who at that time was the Director of the National Historical Museum, who gave us this interview that we are publishing in this article.

Mr. Moikom, how did you get acquainted with Preloc Margilaj’s book “Illyrians speak Albanian-Albanians speak Illyrian”?

A few months ago, when the author Preloc Margilaj was still alive, he sent me his book, from the town of Podgorica in Montenegro, where he was still living. This large format book was subject to scientific motives of special interest. His sudden death left me with a double pledge: the pledge I could not recognize directly and the pledge I did not give my ratings for this book. In part, I was giving him back this mortgage by giving him some thoughts on what I might call his testamentary deed, namely the book.

What innovation does Margilaj’s book bring?

The book “Illyrians speak Albanian-Albanians speak Illyrian” with 470 pages of large format, has an encyclopedic character. The book is the result of long research in time and space, of passionate research in history. Margilaj with genuine philological information, gives in this book wide and multiple panorama. The book is dedicated to anonymous readers of the Balkans, in order to know the true face of the past and in particular the indelible history of the Illyrians. As Herodotus put it: “After the Hindus, the Thracians and Illyrians are the greatest people and if they knew how to organize they would rule the whole world.” The Illyrians are undoubtedly a primitive people, among the most important in the ancient world of Europe. Samerst Frey, has stated that: “The peoples who passed first from the prehistoric to the historical epic in the West, were the Illyrians and in the East the Thracians, organized into tribes, as well as with the organized tribal aristocracy.” An unusual testimony of Pliny, says: “The Illyrians were the first to create the alphabet and passed it on to Italy.” Thus, we encounter a colossal paradox of ancient history. Undoubtedly Pliny knew this truth and did not deny it. But today in historiographical and linguistic studies, it is almost a postulate, almost a taboo, the thesis that the Illyrians did not leave their writings. Çabej once said not without sincere sadness and without pain that: “The Illyrians did not have a Homer of their own”.

Did the Illyrians have phonetic writing, did they graphically record their testimonies?

If I have to say something not without scientific interest for the proto-Illyrians, I can say that the collection of anthropomorphic and geometric graphic signs of the famous prehistoric rock painting of Lepenica near Vlora in a cave 800 m above sea level, dating at least from the millennium of IV BC, is in a way a pictographic massage, which carries messages with a meaning that today we can only imagine but not fully read. Pictographic writing is more a painting than a graphic of thoughts. The painting of Lepenica with almost 19 anthropomorphic figures or other geometric and numerical signs is undoubtedly related to the recording of the mental world of our ancestors. This extreme evidence clearly tells us that the prescriptive phase in the ancestors of the Albanians is documented archaeologically and accurately. It also draws attention to an epochal discovery, which has not been given due importance to date. According to the scholar, the greatest living Illyrian scholar, Aleksandar Stipcevic, the refinement of the literal system is evidenced in southern Mesopotamia, when one of the most enigmatic peoples in human history, the Sumerians, created an extremely high civilization. The Sumerians invented writing in the form of an order of pictograms exactly in the middle of the IV millennium BC. Such rudimentary writing is the origin of later phonetic writing. It is thought that the Far East came from and the Indo-European peoples of today retain the enigma of the genesis of writing. But in 1961 some baked clay tablets of the Neolithic period were suddenly discovered in a place called Tartaria in Romania.

What were those slabs and what did they represent?

Those clay slabs found in several other parts of Europe’s Danube basin caused great astonishment and even a special confusion among paleolinguists and civilization historians. The results of scientific radiocarbon analysis proved that these clay tablets, which bore written marks, were several hundred years older than the clay tablets with the ancient Sumerian writings. The writings, or graphic symbols that are more reminiscent of the pictographic system of the Danube basin, have led scientists to suspect that the origin of writing may have been the source land of Europe rather than that of the Sumerians in the East. The Sumerians, however, have the merit of perfecting ideographic writing, of gradually refining it, of simplifying it by turning it into a system of letters with increasingly simplistic phonetic features, by abstracting and maximizing the symbolic conventionalism of the sounds of the human voice. It is known that phonetic writing was adopted by the Phoenicians and through them spread to the Balkans, to the Pelasgians, to the ancient Greeks and according to Pliny the Testament to the Illyrians, who mediated the expansion and institutionalization of phonetic writing across the Adriatic, in present-day Italy. and throughout Western Europe. I also want to draw attention to the fact that the thesis that the Illyrians did not write their language is not absolutely true at all. It was in southern Italy that archaeologists found several hundred inscriptions called ‘scripta continua’ of a large branch of the Illyrian people, more precisely of the Illyrian Mesopotamian tribe. Mesapic writings have been collected and published. There are some prominent scholars, with big names like Bofante, etc., who have taken the Mesopotamian inscriptions seriously and are categorically convinced that they carry the Illyrian language. I am sorry that Albanian scholars have overlooked this truth. I am sorry that the complex Albanian linguists, ostensibly from the name of a false, romantic or grotesque nationalism have been silent about the Illyrian writings of the Middle Ages.

Have foreigners dealt with these you just quoted?

Contemporary archaeological studies in Italy have paid attention to the Illyrian civilization of the Japiks and the Middle Ages. Italian archaeologist Francesco D’Andria has published archaeological materials, pottery and other monuments of the Illyrian area of the Middle Ages and Japica, but unfortunately this material has not been introduced into scientific circulation and has not been taken into consideration in our Illyrian studies. Çabej, as a colossus of Albanian linguistics has rightly been careful, with a maximum accuracy. Yes, it is Çabej who said that one should not lose hope that one day the archaeologist’s pickaxe will bring to light evidence of Illyrian writing in Albania as well. In fact, as Stipçevi ka pointed out, there are almost 20 inscriptions found in Northern and Southern Illyria, which to this day are not explained in either Greek or Latin.

But who took them seriously?

I also want to bring to relief a wonderful onomastic fact: only from the quarries, the Kionisk discovered in the archeological city of Durrës, about 200 Illyrian names have been found. Illyrian onomastics is an indisputable fact in science. Karl Paçi and Karl Traimer have taken Illyrian onomastics seriously in scientific optics. There are some undeniable books dedicated to the Illyrian language. I am mentioning two authors of large world format: Russu and Mayer. I studied their two books many years ago. I know well their philological results as well as their unwavering conviction for the linguistic entity of the Illyrians. So, Illyrian is by no means a phantasmagoric reality. Illyrian onomastic geography includes the Balkans and a large part of Europe. The comparative language school, mainly German, made a great qualitative linguistic hop. It was even passed on to the thesis of an extreme panilirism. Scientific criticism of pan-Illyrianism is right, but the transition to the position of an anti-Illyrian critique is grotesque and ridiculous. The rocky truth is in the middle. Scientific truth exists and cannot be denied. These I said above constitute the conceptual bed of Margilaj’s book.

How is the book structured?

The book in question starts with an introduction by the author as well as a review by Prof. Nikolle Gj. Margilaj. It is clearly explained in these two texts that exploring the truth of the Illyrian language is a tireless work and that belongs especially to the future. The onomastic elements, toponyms, horonyms, hydronyms, anthroponyms, theonyms, have to do with ethnogenesis and are already an undeniable linguistic nomenclature. There can be no history of antiquity of Europe without the Illyrian linguistic nomenclature, which survives in paleodialectical oases, in archaic forms of morphology but also in many elements in today’s semantic sense. Illyrian civilization is a sui generis civilization, surviving among Albanians. It has undergone assimilation, deformation, metamorphism, but without losing its originality. The tragic history of the Illyrian people is also the history of centuries of conquests, cultural homogenizations and endless intermingling of other languages of the continent. But it has not been possible to achieve complete whitening or the xero sign of everything. In this sense Margilaj’s book is against nihilistic theses, which have almost acquired the status of eternal prejudices against the Illyrians. The book is structured in 9 chapters. Chapter I deals with onomastics, toponyms, horonyms, hydronyms and the meaning of the terminologies of the Illyrian world in Southern Illyria, Dalmatia, Byzantine Illyricum, etc. Chapter II deals with Illyrian andronyms, proper names, metamorphoses and some etymological keys of the characteristic Illyrian names. Chapter III is based on the Indo-European roots of the Illyrian language, ie it deals with comparative reports. Chapter IV deals with the names of Illyrian myths and cults, theonyms, the Pelasgian myth of the creation of the world, and some explanations of mythological figures. Chapter V deals with Illyrian toponyms outside the Illyrian metropolis. Chapter VI is dedicated to the Illyrian-Thracian connections, which constitute the essence of both the secret and the conception of the Albanians as a living and special people of the Indo-European family. Chapter VII deals with the etymology of the names of the great Illyrian tribes and some ethnographic institutions. Chapter VIII studies the traces of the Illyrians in Italy, the mutual relations of the Etruscans with the Illyrians. Chapter IX studies other ancient civilizations and the undeniable antiquity of the Albanian language. At the end of the book is an epilogue, which has a conclusive character. /Memorie.al