By Dorian Koçi

Memorie.al / Words that express great concepts often seem to come from a divine origin, but in fact, they reflect a well-known principle of semantics, of identifying concepts with the things that have represented them. So, for example, few can think of or remember if they have read somewhere that the word tragedy, so necessary to understand human pain, suffering and catharsis, has at its center the gift that it was given to the winners in the games and celebrations organized in honor of the god Dionis.

This gift, which was the goat very worthy of the mountain countries, where it was considered a sacred animal to breed the economy and therefore to be sacrificed, seems to plebetiize a little the high aristocracy of words, which is reflected in the form of the tragedy, but in it indeed, those who have given life to this type of stage art are the wonderful tragic actors.

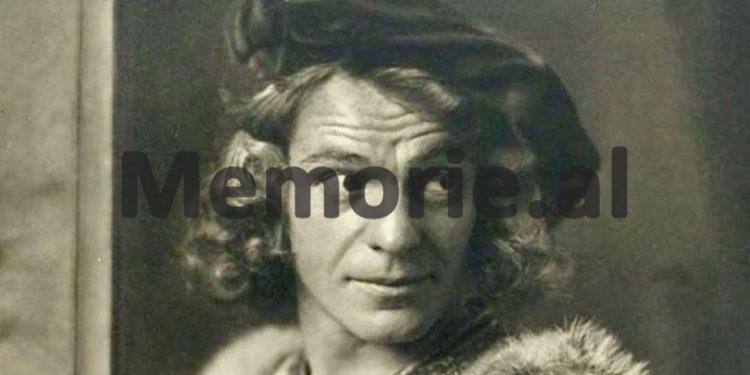

Our ethnos and nation had the good fortune to give birth to one marked in the memory of time, with the name of a great hero of antiquity, like Alexander, and with the last name of a great prophet of humanity, like Moses.

I don’t know what better combination the word tragic could find, than the combination of these two names in one person, since Alexander the Great was above all a cultural hero, the man who in every advance of his armies, built and important cultural institutions, spreading civilization and Moses a prophet, who led his people to the Promised Land and received the ten Holy Commandments, spreading the word of God.

This kind of combination and overlap of cultures can only be found in the Illyrian Peninsula, where Alexander Moses came from, since he, like Alexander the Great, is a cultural hero.

What might Moses have inherited from his country of origin? The cities of Durrësi and Kavaja, where did you spend some years of your life? How might these cities have influenced his personality? In 1849, the British landscape painter Edward Lear wrote about Durrës that; from the appearance of the castle, it looks like a Norman style building, although with lots of patches and repairs.

Its fortifications extend down the hillside to the water’s edge, where they join the city walls. In some parts of them I noticed some armored shields, with some bas-reliefs in the form of carved owls. The combinations of the surrounding landscapes are very elegant and wonderful, from any Albanian landscape I have seen.

Then he writes about the rural beauty of the surroundings of Kavaja, which consists of large olive trees, spreading their branches over paths and broken banks, alleys, some mosques and a tall clock tower, figures of gegs dressed in strong colors black, red, white; cemeteries with glowing graves; then garden trees towering over red roofs and tall white chimneys; olive green to blue ripples; further flat and endless meadows, down to the sea, with endless herds of cattle; while the lines of the low, pale hills in the south-west, as well as the blue Adriatic with Durrës at its cape, melt sweetly into the horizon.

Perhaps these endless refractions of landscapes would reflect in his magical voice. Perhaps the religious and architectural diversity would affect his temperament, his whole life and passion. Stefan Zvajg, would express his voice; “The voice caresses itself, slips woven thoughts up and down the scale, like a cat purring in musical octaves, which rise and fall along the entire scale of the resounding instrument, the throat. Sometimes a person closes his eyes just for a hop, to feel his speech as music…”!

But did Moses feel himself Albanian? This is how he expressed himself in the meeting of June 29, 1920, in Vienna, with the Albanian students, moved by their considerations and enthusiasm. “Dear friends, thank you very much for the honors you have given me. I have been in many feasts, in many meetings, I have felt many joys, but this one of this night is a different joy.

Please believe me that I have never been as happy as I am tonight. I cannot tell you the pleasure I feel when I hear so many beautiful things from you about the progress and development of the Albanian people…”!

Moisiu gave the stage the choleric Albanian temperament, the Italian Mediterranean tenderness and the cold German logic. “Albanian, Italian, German, European – citizen of the world”, theater critic Rudiger Schaper writes about him. But above all, in Moses, the tragic is revived that prevails over the sublime.

“No one died so often and so wonderfully on the stage as Moses. In Tolstoy’s “The Living Corpse” alone, during the years 1913-1935, he shot himself with lead, over 1,500 times”, says the German critic, Rudiger Schaper, in his biography of Alexander Moisiu.

Very difficult, in fact, to summarize all four of these characters in one, and at the time when his people were experiencing tragedies of persecution, entering and exiting the scenes of history. But Moses was a genius, so the existentialism in Hamlet’s monologue; “To be, or not, to be”, gained momentum and resembled a poem dedicated to life.

“Hamlet was written for Moses and Moses was born specifically to play the prince of Denmark,” says Max Brod, the friend and biographer of Franz Kafka, who together with Kafka had the fortune to follow Moses, during 1903, at the German Theater of Prague.

But what was so charming about Moisu’s voice and his theatrical play? Why did cold countries, as the scene of great tragedies, like his acting so much?

The answer is given by another great personality of Germanic culture, Stefan Zvajk, when he wrote that; “The man of the south always remains the man of the south. In order not to freeze, he takes the sun of his country with him wherever he goes.”

Zwajk, like everyone else, who lived in the Great Empires, most likely did not know the exact origin of Moses, or identify him, as Italian, but his definition, in fact, remains proverbial.

Albanians are really communicative people and at the same time, full of passion, so if we ever changed our minds, to stop being called sons of eagles, Moses would come to our aid, to call us as; “people who take the sun with us wherever we go”.

This can immediately turn into a cultural dilemma, and always there if we want to respect the word more, Aleksandër Moisiu, the suspicious Hamlet of the Albanian world, will come to our aid. Memorie.al