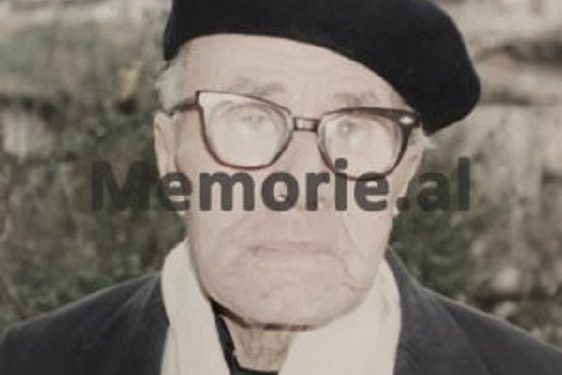

Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al publishes the unknown story of Zija Muka, an intellectual from the city of Shkodra who during the period of the Zog Monarchy studied in Italy for a Geometric Technician and after returning home left that profession and devoted himself to journalism, working in several press of that time and later as Secretary General in the Ministry of World Affairs and Agriculture. During the occupation of the country he was assigned to work in Kosovo, where he found himself and the end of the war, but could not return to Albania after the Titoist regime accused him of being an “accomplice of the German occupiers” and sentenced him to eight years in political prison. from where he could be released in 1949, when relations between the two countries broke down and he returned to his hometown of Shkodra, as a worshiper of King Zog’s Monarchy, he refused to take part in all the elections held at the time, until the fall of the communist regime!

Throughout the 45-year period of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime, not participating in the elections, or casting a vote against the Democratic Front candidates, represented by the ALP, constituted a heresy that would bring many serious consequences to the person who ‘agreed to go to the ballot box and in the worst case, this action was “paid” even in prison. But although quite rare, there have been cases when various persons refused to vote and did not participate in the elections organized for the People’s Assembly or for the People’s Councils, abandoning those elections openly and demonstratively. For example. Zefe Mala, founder of the Communist Party, who after several years in prison and internment, in one of the letters sent to Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu, would write, among other things: “Your power ends on the doorstep of my house”, or Hamit Gjylbegu from Shkodra , interned in Elbasan, who never voted in the communist regime by openly demonstrating a boycott of them. Another character from the few rebels who did not vote during the communist regime, was the intellectual from Shkodra, Zija Muka, who is remembered by all his fellow citizens for not participating in all the elections before the ’90s. But unlike Zef Mala and Hamit Gjylbegu, Zija Muka found different ways not to vote?!

Who was Zija Muka, what was his past, why did he not participate in the elections and what were the consequences of his refusal to vote? In this regard, we know the article that we publish below exclusively for Memorie.al, which we have built on the basis of information we have received from some of his relatives, but also other people who have known him closely.

Who was Zija Muka?

Zija Muka was born in 1912 in the city of Shkodra, whence the early origin of his family, well known in that city. The big house of the Mukajs, built for several hundred years, is still located today in the center of the city of Shkodra, very close to the Parruca mosque. His father was a citizen of Shkodra, Zija’s mother was the daughter of the famous Oso Bilal from the city of Ulcinj, who represented the people of Ulcinj in talks with the High Gate in Istanbul, to fight against the Montenegrins. Zija’s father, Ramadan Muka, had a degree in economics and during the years of the Zog Monarchy worked as an economist in the New Bazaar of the city of Shkodra. While his uncle was Shefqet Muka, the director of the first secular gymnasium in the city of Shkodra. Among other things, the Muka family has been known for its friendly ties with the Vuciterni family of Kosovo and the Mullets of Tirana. Likewise, Zija Muka’s family had very close friendly relations with Taip Alia (father of the former communist president of Albania, Ramiz Alia) and at the house of Zija Muka’s sister (who was married to Zog’s minister, Sali Vuciterni) Ramiz Alia has spent a large part of his childhood.

Head of Zog Ministries

After finishing her studies at the secular gymnasium in the city of Shkodra, with very high results, Zija Muka went to Italy where she took a course in geometry, but after returning to Albania, he did not practice that profession at all. In the early 1930s he devoted himself to journalism, working for a long time in various organs of the Albanian press of that time, he was well versed in several foreign languages. Early in his career as a journalist, he worked as an editor of historical columns and later as a journalist of sports websites for Tirana and Shkodra. As a sports journalist, Zijai attended several international activities in the Balkans, where Albanian athletes participated, such as in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, etc. During his years of study in Italy, Zijai met and befriended the famous Albanian painter, Ibrahim Kodra, who also painted a portrait of his compatriot, which Zijai kept as a precious memory until the end of his life. In the mid-1930s Zijai left journalism and began working in the state administration of the Zog Monarchy, as Secretary General of the Ministry of World Affairs. Even after the invasion of the country by fascist Italy, he continued to serve in the state administration, working as Secretary General of the Ministry of Agriculture. During that period, the Albanian government, which also had Kosovo under its jurisdiction, appointed Zija as its representative in that province to distribute aid. This task, which he fulfilled honestly until the end of the War, in December 1944, created some problems for the Titoist regime in Belgrade, which accused him of being an accomplice of the German occupier and did not allow him to return to Albania.

19 years in prison in Albania and Yugoslavia

The Titoist regime in Belgrade not only did not allow Zija Muka to return to Albania, but brought her to trial and sentenced her to 8 years in political prison, where the prosecutor was Ali Shukriu, known as a pro-Titoist. Zijai served his sentence in the Nis prison until 1949, (a year that also marked the breakdown of Albanian-Yugoslav relations), acquitted after several successive demands. The Titoite regime not only acquitted him, but asked him to stay in Yugoslavia, working as a surveyor in the town of Ulcinj, where he had his tribal people from his mother. But Zijai refused to stay and work in Yugoslavia and in the same year returned to Albania, settling in the city of Shkodra. For many years he was out of work, as the communist regime of Tirana did not like him because of the functions he had during the years of the Zog Monarchy. Zijai, who was also the only brother of five sisters, was forced to take up various private jobs to make a living. He exercised his private activity until ’66, when the communist regime banned the private sector by law. At the time, the communist regime sentenced Zija to 11 years in prison, allegedly for some unpaid debts he owed to the Commercial School in Shkodra. But in fact, his arrest and conviction came because of his attitude towards the communist regime in power. He had been somewhat open since his return from Yugoslavia in 1949, except for Zogist political convictions, which Zijai did not hesitate to express openly with his friends, since ’45 he had never taken part in the elections. This was the main reason for his imprisonment and his sentence of 11 years, was rather a warning that he would not refuse the vote. As a result, Zijai suffered only two and a half years in prison and was released, saying he had “won innocence”.

He has not voted since 1945

But why did he never go to the polls and how was Zija Muka justified for his non-participation in the elections held during the communist regime of Enver Hoxha? The main reason for not voting was his political convictions, as he was an ardent supporter of the Zog Monarchy and as such he was also an opponent of the communist regime. Based on this fact, he had decided never to vote, both in the elections for the People’s Assembly and the local elections for the People’s Councils. But knowing well the nature of the communist regime, which had nothing to do with imprisoning him, Zijaj did not openly oppose the vote. He used some kind of excuse to defend himself for not voting. Given the fact that he had come to Albania only in 1949, Zijai said that he did not appear in any of the civil status registers and normally not even in the voter lists. When asked in Shkodra to vote, he said he had his name on Tirana’s civil status lists, having resided there since the mid-1930s and during the occupation. Also, another excuse of his was that he allegedly had his passport in Kavaja, because Zijai had lived in that city for several years, when his sister Pertefe Muka Mulleti, had been interned with his family. He used these excuses even after his release from prison in 1968, a prison which he had done precisely because he did not participate in the elections. Due to the fact that he became a very problematic person for the regime, some cities where he had lived, such as Shkodra, Tirana and Kavaja, did not want to have him on the voter lists, as he reduced the turnout. Not only did he not want to vote, but he did not want to have any connection with the regime and to concretize this, in the room of the house where he lived (in Parrucë), he had cut off the electricity and drinking water provided by the state. But in order not to create problems for family members and relatives, he lived completely alone and did not get married. Zijai spent most of his time in his room reading books and browsing the rich documentary archive at his disposal. In his room, he hung on the wall and a picture of Queen Geraldine, to whom he had the same adoration as King Bird and his close friends spoke openly about him. He rarely left home and his closest friends were Shkodra intellectuals, known as anti-communists, such as: Hamit Gjylbegu, Izet Bebeziqi, lawyer Koliqi, the famous pianist, Ida Melgushi, etc., and some Catholic clergy that the communist regime considered as “reaction leaders”.

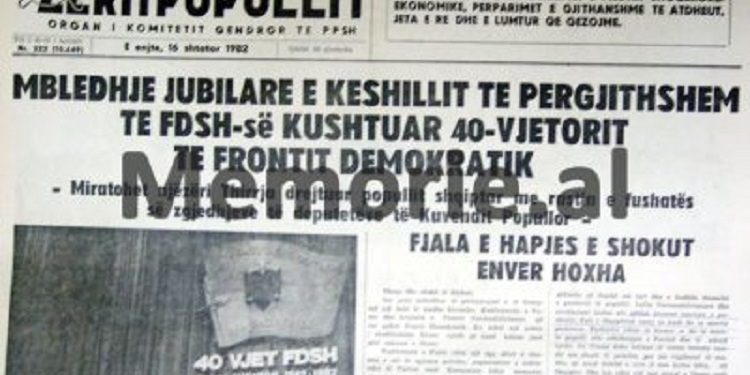

Pressure to vote

The communist regime’s constant pressure on Ziya to run in the elections did not cease even in the early 1980s, when he was already at an advanced age. At that time pressures began to be channeled towards his family and tribe, so that they forced him to vote. Thus, in the 1982 elections (for the People’s Assembly) the Shkodra Party Committee called his two nephews, Jusuf and Vildan Tufi, telling them to force their uncle to vote, as otherwise they would be fired as an engineer and lecturer at the Higher Pedagogical Institute. After much prayer, they forced Ziya to go to the polls. Holding him by the arms, they escorted him to the polling station, where they introduced him to the relevant commission. Zijai took the ballot paper and after going to the secret room, an action which no one was doing at the time, put it in the box demonstratively. After that, he left alone for his home and the news spread throughout Shkodra that Zija Muka had voted. But this had not been true, for when the ballot boxes were opened, a white paper was found there, different from those of the ballots. He had been inserted by Zijai and the letter given to him by the commission, he had taken it with him in his pocket and burned it as soon as he got home. In another case he asked the commission to enter the secret room, and they, knowing that he would vote against, so as not to spoil the figures 100%, told him to leave, as he allegedly did not have his name on the lists. them. Throughout the communist regime, Zijai did not stop writing to Ramiz Alia (who also had a cousin) to demand his rights, but never received a response from him.

After the ’90s, he voted for Leka Zogu

Zija Muka, was lucky enough to live long and participate in the elections that took place after the ’90s, when that regime collapsed. In the first pluralist elections of ’91, Zijai went to the polls and after receiving the ballot paper with the names of the electoral subjects, asked for the name of Leka Zogu. And when he did not find it, he marked it himself with a pen and then put it in the ballot box. In the next elections he regularly voted for the Legality Movement Party, as he was an old supporter of that political force and personally of King Zog. Zija Muka passed away at the age of 89, on January 23, 2003 and he is remembered by all his fellow citizens in Shkodra, as the man who never voted during the communist regime of Enver Hoxha. / Memorie.al