By Eugene Merlika

– The publicism of Don Lazër Shantoja and the unresolved knots of Albanian historiography –

Memorie.al/ On March 5, 1945, the first martyr of the Albanian Catholic Church in the communist era, Don Lazër Shantoja, was shot. He was arrested by the “liberators” of Albania, a little more than two months ago. In those two months he had suffered the most inhumane tortures imaginable. The mutilated body, with its limbs sawn off, that March day was thrown into an unnamed pit, together with that of Sulçe Beg Bushat.

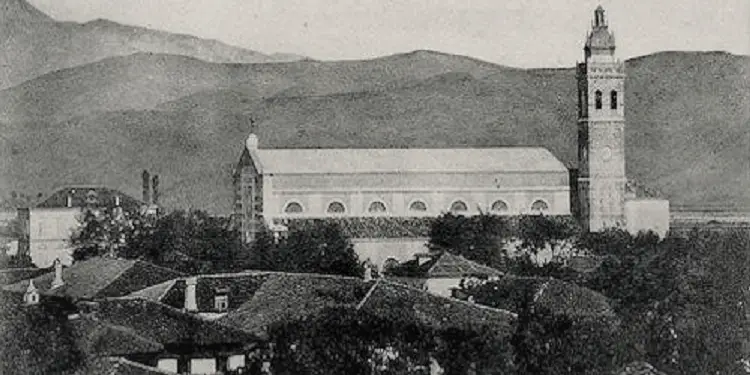

This is how the circle of life of one of the most prominent erudite of the Albanian society was closed, whose personality stood out in many fields of the art of letters, giving a really powerful help in the cultural life of his compatriots. He was a son of the Catholic tradition of Shkodra, the most representative city in the field of Albanian culture. He grew up and was formed, as a man and as a priest, at the Papnuer Institute of his city and at the University of Innsbruck, Austria. It took root in the tradition of the Catholic Clergy that had the primary role in preserving, cultivating and strengthening the national identity and culture of the Albanians, in the long centuries of the Ottoman occupation.

Shantoja entered the broad circle of intellectual Catholic clergy, who, from Buzuku, Bogdani, Bardhi to Fishta, Mjeda, Gjeçovi, Marlaskaj, etc., possessed with their personality and religious and cultural activity, in the span of time centuries, in the sphere of Albanian resistance to the crushing danger of invasion, representing the backbone of culture and the national idea. If Christian religious institutions in post-Roman medieval Europe had the well-known merit of preserving the values of the classical culture of Greco-Roman antiquity from the danger of their extinction by barbarian tribes, the Albanian Catholic Church in our Middle Ages, which lasted until the century twenty, carried on his shoulders the fundamental elements of the revival of the Albanian nation.

Don Lazër Shantoja, a 24-year-old boy, newly ordained as a priest, is appointed secretary of Archbishop Lazër Mjeda. Here began his almost thirty years of activity in the service of the Church, the culture and the Albanian society in the period crowded with events, which determined the progress of the creation and strengthening of the first united Albanian State. Shantoja’s activity, thanks to his rich and genuine intellectual formation, was diverse. A born poet and an accomplished prose writer, an unattainable orator and a true political tribune, one of the most talented translators of Albanian letters and a deep connoisseur of classical and major European languages, an attentive researcher of the literary, sociological and philosophical thought of European elites, Don Lazër Shantoja, stood out in a special way for the help given in the field of journalism and social thought of the first decades of the twentieth century.

Shantoja Publicistika has the crystalline beauty of an alpine lake, into which torrential streams flow when storms batter the surrounding mountains. Those storms are the political events lived in the first person and reflected in his articles. The circle of the author’s gaze is quite open and his many interests all revolve around a central idea that is his credo: the Motherland, Albania, its development on the road to civilization, in the Western direction. It is an immovable idea of the author, his friends and comrades-in-arms, which illuminates and gives meaning to their lives that traverse a multitude of paths, sacrifices and privations of all kinds. We find his articles published in various notebooks inside and outside Albania, and in them a multifaceted personality comes to the fore.

In the cycle of writings published in the “New School” of 1921, the author’s desire to instill in his compatriots the principles of civilization, of the truth derived from the teachings of philosophers and the experience of humanity over the centuries, stands out. The principles of education, morality, society in its various manifestations such as school, work, careers, arts, etc. are listed in these writings. They bring examples of outstanding people, their difficult path, successes, fame and achievements with the sole purpose of encouraging the noble ambitions of Albanians who had to build everything with their own hands. With a simple and convincing style, Shantoja will tell his compatriots, especially young people, that there is no bridge that cannot be taken if one has the will and desire to move forward. They are valuable lessons that are given to a people that have just entered the path of development, after centuries of foreign occupation that had not helped that development at all.

The author is part of that elite of this people that tries, by all means, to encourage in them the desire, the interest, the desire to go forward, to put to the test the intelligence, the strength of will, the patience, qualities that are so necessary for past the difficulties and obstacles that time and historical circumstances brought before the Albanians. Through the examples of many outstanding people, whose lives had begun in great difficulties, but had ended with stunning successes in various fields of science, art or politics of their nations, Shantoja conveys the message of optimism, of faith in strength and the stability of its people. At the same time, he tells the Albanians that nothing is achieved easily, that nothing is given, but earned with hard work, sweat and sacrifices. In this way of reviving the nation and trying to follow in the footsteps of civilized peoples, everyone must do their part. This applies to generations as well as to individuals, to princes as well as to ordinary citizens.

Christian and democrat Don Lazri tries to eradicate the prejudices of the caste, of the chosen race, of “good families”, especially in the school system, in the minds of teachers who have a primary role in the development of the nation. From their hands will emerge those who will move Albania forward in all fields, administrators and statesmen, artists and professionals, that intellectual elite that will become the backbone of a society that should aim to burn stages, to gain the lost time to enter with full rights in the ranks of civilized peoples. Albania needs teachers to be aware of the major mission that awaits them and to see their work in the prism of not immediate profit, but future benefit.

About the author: “It is well known that the teachers only earn by the mouth of their mouths, at the world they have no other gain than by keeping their breath and keeping their stomachs active; true gains, spiritual gains, ideal, I was pleased to be recognized and made one of the pioneers of the country, you planted a seed that one day will bear great fruit, these gains should be with the ideal teacher.” (p. 63)

Shantoja’s thought precedes the development project of the Albanian society, as it is in itself quite advanced compared to the dominant mindset of the time. He whips the traditional patriarchy and masculinity characteristic of the Albanian worldview, advises tolerance and respect of thought, although the concept of women does not escape the mentality of the time and becomes unacceptable for the stage of development of today’s Albania.

The problems of the economy are seen under the prism of the statist mentality. The Government, the State must be regulators of the economy and even determine the direction and way of operation. We come across protectionist thoughts that, at first glance, go in favor of Albanian producers and buyers, but that create a frozen and closed economy which, over time, has no ability to develop.

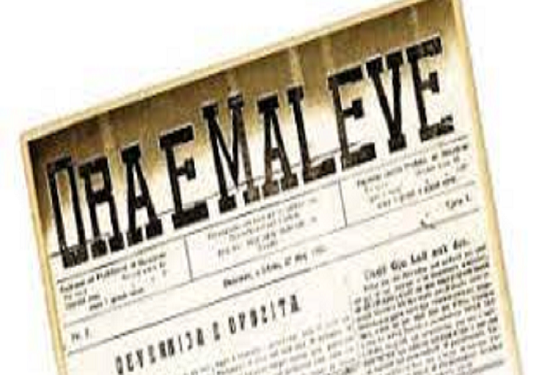

The press, its strength, importance, function, influence on the state and society are another topic of Shantoja’s writings. He is quite critical, especially with regard to the written language, which, to borrow an expression of Budi, “is being corrupted and bastardized”. “More than anything else, we will criticize the phenomenal incompetence of many writers who, after preparing for studies, take up and write crossly on issues for which they have no competence…! On the contrary, who begs me to examine the most delicate aspects of philosophy, morality, sociology, all of them are competent, even the maids…! What kind of education can be given to the people to be a pillar on their feet with the trowels of the pen, a pen many times sold and partisan”? (p.128) asks with legitimate indignation in the pages of the “Mountain Hour” the erudite who had the privilege of studying in the original languages the best achievements of the cultures of the West.

Shantoja was a supporter of the free and independent press, the one whose aim is the presentation of the unbiased truth, a press that is not subject to the power of money or power, because in that case it turns into the opposite of the mission his, which is the formation of the opinion and familiarization of the reader with the course of events of every day. His interest covers many spheres of Albanian life, and the subject matter of his writings covers almost the entire range of its phenomena.

The writings give a not at all optimistic picture of the progress of the Albanian State, of its economic, financial and administrative problems. In them, an anatomical analysis of these phenomena is made and emphasis is placed on an overblown bureaucratic administrative apparatus that weighs like a rock on a weak and underdeveloped economy, not to mention peace. “Are you saying that there is a need for everything personally? Is all this used personally because Albania and its people need them, or why do these people have to live on Albania’s back…”? (p.131) asks the author with pain. You can feel the citizen’s concern of Shantoja, which penetrates to the darkest recesses of his country, which echoes the poverty of the majority of the people, which this way of organization and functioning of the State does not help to alleviate at all.

The concern is sincere, felt, in accordance with the mission of the parish priest who touches the problems and shortcomings of the ordinary Albanians who fill the parish every Sunday, who revolts and explodes when he sees that: “how money is wasted, how money is wasted of the poor, of the people, of the bulk, of the worker. To keep people who are parasites…… who do not know how to live, except behind the back of the State, with an employee to steal you with protection…”. (p.131) We are not dealing with a Marxist type of instrumentalization of the phenomenon, but with the deep pain of one who loves his people with all his heart. This pain reaches the point of revolt and despair when you see that the criteria for hiring the multitude of employees are not merits and abilities, but clientelism and political hatred. They are open wounds that have never been closed until our days, when we still face these phenomena, prejudicing development.

In the articles published in “Mountain Clock”, the pulse of the patriot is strongly felt, but there is a large dose of realism. The problems of the country are faced with the heart but also with the mind, mainly in a critical direction. The writer has a clear objective around which the whole mass of his concerns revolves: Albania that must walk the path of development, progress, civilization. The phenomena that hinder this progress are on the blade of the publicist’s criticism; they are the subject of his political pamphlets, the object of whipping, sometimes with rather harsh tones. But Shantoja is not a nihilist; he does not see only darkness in the present and future of his nation. He has the ability to see the light in idealistic people who are trying to pave the way, on which future generations will build the modern state.

“Albania was made by the intelligentsia and the intelligentsia will keep it, or I will not have Albania! The reservoir of natural strength in Albania is its intellectual center. When we feel the sunny and detailed talks of a Fan Noli, the dialectic of Luigj Gurakuqi, the electrifying speech of an Ali Kelcyra, the surgical language of a Stavro Vinjau, the legal reasoning of a Koço Tasi, we forget our own explosions socme and a single sweet word rings in our ears: Yes! There is Albania!” (p. 143)

Shantoja is an idealist, but there is some pragmatism in his idealism. The history of the world has taught them that peoples, on their way of development, have achieved their goals when they had capable leaders dedicated to their cause. In their presence, hope fades and hopes for the future and faith in it is born. This hope finds sources of food in young people, in students who, in different countries of Europe, prepare themselves with knowledge, culture and professions and are ready to implement these in their homeland. This is how the rich cultural elite was created in Albania in the thirties, which would be mowed down mercilessly after 1944, as “bourgeois intelligentsia”, opponents of the communist regime. It seems that it is a historical fatality for Albania that it must always dream of a new generation that must take it out of the swamp of backwardness and summer on the path of progress.

“Ideas are born, grow and bear fruit only in a virgin land; in the mind and in the heart of the young: from them come out and clean the decay and everything stops the progress or crystallizes in the forms of a time that it has created”, (p.244) wrote Don Lazri in 1924. Eighteen years later, Mustafa Kruja, then Prime Minister of Albania united with Italy, in the interview given to the well-known Italian journalist, Indro Montaneli, says:

“We have a tired, backward aristocracy, with principles that no longer fit our time, a bourgeoisie deficient in numbers, means and training, an extent in which 70% is illiterate. Our hope is in the youth. Young people have momentum that sometimes pushes them far forward, but they are protected with a pure love for their homeland and sincerely aim at forming a national and self-awareness. Many of them go to study in Italy. They return from there with the impatience to raise their country to the Italian level. Impatience often leads them into mistakes, but blessed be he who mistakes for generosity. I don’t want blindly obedient young people, but conscious and disciplined. Of course, the former would make my task as a government easier, but they would not give me any guarantee for the future. For us, what has value is only the future”.

Today, after another sixty years, the hope to bring Albanian politics out of the mud and the country from the last ranking in Europe is again dependent on the young. Although we often encounter disappointments in that direction, since not everything that glitters is gold, I think that the continuous renewal of Albanian politics is a necessity. Unfortunately, it is not seen in this prism by a good part of the ruling class that maintains the positions won, regardless of the fact that time passes and there cannot be people for all seasons. However, the activation of many young graduates abroad in the state administration is something encouraging.

Among Shantoja’s journalistic writings, I think that a first-hand place is occupied by those dedicated to the events and characters of Albanian politics in a period of almost a quarter of a century. The writer was a keen observer of them and, more than a participant with important functions was a conscious victim of those events. He suffered imprisonment, exile and exile even though he never held any high position; he was not even a member of parliament. But the priest-poet is in symbiosis with those events and their protagonists and his penda, together with the oratory, sometimes decisively influence them. Shantoja is always coherent with himself and the principles. Opinions may differ, but the evaluations have a defining and immovable criterion: the interest of the Motherland. This is the true and only meter that serves as a unit of measurement for everyone and everything.

He was positioned on the side of the antizogist opposition. His idol was Luigj Gurakuqi, who: “With an exemplary patience and tirelessness, gave his life for the ideal of a free, great, prosperous Albania.”, the leader of the Opposition in the years 1921-’24. The martyrs of freedom and democracy were Avni Rustemi, Gurakuqi himself, Bajram Curri, Hasan Prishtina, Elez Isufi, Zija Dibra, Ramiz Daci, Zef Ndoci, Mark Raka. The comrades with whom he shared his beliefs and ideals were: Mustafa Kruja, Stavro Vinjau, Qazim Koculi, Xhevat Korça, etc. On the altar of the nation were his best known colleagues such as: Fishta, Gjeçovi, Mjeda, Harapi, Marlaskaj etc. In the opposing field, there was Ahmet Zogu, Prime Minister, President and then King of Albania, synonymous for a part of Albanians with evil in power, surrounded by supporters like: Eshref Frashëri, Mehdi Frashëri, Faik Konica etc., or murderers and masterminds of murders such as: Baltjon Stambolla, Çatin Saraçi, etc.

In this micro universe of political figures, Shantoja penetrates with the power of a pen, leaving us his convictions and thoughts engraved. They are the result of objective and subjective views of the author, sometimes even of his political passions. But still, they are important evidence, because they come from the pen of a person without prejudice, who evaluates based on the facts. The periods to which the writings refer are those 1920-’24, the time of exile 1924-’39 and the years 1939-’43, when Albania was occupied by the Italians but had a special status, because it was called united with the Kingdom of Italy .

Regarding the events of these historical time periods, the author takes different positions. With an advanced democratic worldview, he unreservedly supports the June 1924 Revolution and those young intellectuals of the “Union” who were its flag bearers. Surprisingly, he devotes little writing to the Government of Noli and more to the political exile that followed its fall. Perhaps this fact testifies to a certain disappointment that publicist Shantoja suffers from that government and primarily from the Prime Minister, whom he strongly attacks in a later article. From the exile in Yugoslavia, Austria and Switzerland, an attempt is made to analyze the state of real Albania, which is represented by the evolution of the power of Ahmet Zogut to the Kingdom, but also the alternative one, the face of the anti-Zogist Albanian political exile. In this state of strong and permanent conflict, there seems to be no room for talks and agreements. For Shantoja, as for all the political exiles outside the Motherland, “The world has realized that in Albania a bloodthirsty President rules, a President who drowned the day before the sun, a President who talks to the sicari himself, who promises the help of a foreign power, which promises them quick release, monthly salary…” (p.370)

But this political opponent, this “bloody President”, when he sees him unjustly discredited by an Austrian newspaper, has the courage to ask the Austrian Chancellor, Dr. Seipel, his intervention to restore the prestige of the then Albanian Prime Minister. It is one of the pearls of this book, an ideal example of political morality at a high level, an expression of the harmonization of political struggle with its ethics and respect for institutions, a style lesson for today’s politics in Albania and beyond.

For his part, Zogu was aware of the intellectual strength of his opponents, but he also knew that their European mentality did not find a plowed ground among the Albanians who needed time to digest the fat layers of the Eastern worldview, inherited from five centuries. He tried with all the means to make this Opposition harmless, scattered and divided into groups, states and different political persuasions. This war at a distance continued, amid insults, curses, denigrations and mutual quarrels, until April 7, 1939, when Mussolini and Ciano decided to add the Albanian Kingdom to Victor Emanuel’s Crown, sending the invading armies to its shores.

Like many others, priest Shantoja left the parish in the Bernese Jura and returned to Albania “liberated” from the “tyranny” of King Zog. He saw the changes with hope and faith for the future. He did not call the invasion of the country a tragedy, on the contrary, as a means to unite with Italy and, through it, with civilized Europe, where he dreamed of seeing his own country with all its attributes. The writings of this period were probably the strongest indictment that the communist justice made to the first martyr of its laws. He openly and forcefully defends the union with Italy, not because he is sensitive to its interests, because in previous writings, especially regarding the murder of Gurakuqi, he speaks quite harshly about it.

In this union of Crowns, he sees the possibility of Albania walking on the path of progress. If he has to choose between independence in poverty and backwardness, or dependence in prosperity and progress, he chooses the second. He belongs to the ranks of Albanian intellectuals and politicians who considered relations with Italy strategic and priority, friendship with the people across the sea as fundamental for the future of their country, and the occupation as a temporary phenomenon that did not affect the essential essence of Albanians, of those who were called “Italophiles” sometimes with contempt and sometimes with contempt or hatred. At that time, the most prominent figure was the leader Luigj Gurakuqi who, for Shantoja as for many others, had been a standard of patriotism.

Going a bit out of the framework of the close conversation about Don Lazër Shantoja’s publicism, I wanted to open another area of discussion that seems necessary to me and that is triggered by reading the book. How has our official historiography treated and continues to treat these events and figures that fill the pages of the book we are talking about, and is there room for changes in that direction? Analyzing the three main periods dealt with by Shantoja as, ‘June Revolution’ and ‘Anti-Zogist Opposition’, ‘Zog’s reign and his role’, ‘Fascist invasion and union with Italy’, for more than half a century, they seem to have been treated only in Manichean form, in the black and white view.

For the communist historiography that, unfortunately, still through researchers and the mind, continues to dictate its logic in different forms, the Revolution of June 1924, has been an epochal event in the direction of the democratization of Albania, the Zog period a dark time of tyranny and unification with Italy, the biggest tragedy for Albania.

Today, when we have left the past centenary behind us, with all the atrocities that totalitarian ideologies marked with internal consequences for the world and for us, it seems to me that the time has come to make an objective, accurate and true balance of those events, of their causes and consequences, but also of the lives of their protagonists. It must be a balance without political passion, subjected to the cold analysis of a reasoning that must have as its central axis only one idea, the true interest of Albania, away from ideological schemes, as a subject to grind in its mill only the historical facts are clear, pure and not distorted. Scholars, who must write a true history of our Country, must be like impartial judges who must examine those facts to extract from them the indisputable truth. It would be their mission to untangle many unresolved knots of our historiography and assess, in their true dimensions, the political figures involved in them. I believe that this is one of the main tasks of the new generation of Albanian researchers, unfortunately few and lacking, especially in this field.

It is their duty to liberate the historiography from the terms “traitors of the motherland”, “enemies of the people”, “sold out”, “criminals” and other slurs of this type, which a climate poisoned by communist arbitrariness has mercilessly projected on to. I am convinced that the frame that would emerge from such a work and that would be the true picture of our past, referring to the historical periods that Don Lazër Shantoja writes about, would have a completely different look from what we find in history texts and partly also from what we see in his writings.

Perhaps we would find the Revolution of June 1924 and the government of Noli, as one of the biggest mistakes of a part of the political class of that time, and Ahmet Zogu, not only as a tyrant who orders the murders of political opponents, but also as a from the most prominent statesmen of this nation, with a fundamental help in the formation of the structures of the Albanian State and its progress on the contemporary path. Likewise, the so-called “collaborators”, not as “traitors” and “sold out” to fascism, but as patriots on the upper level who, in order to protect the interests of their country, in one of its most difficult moments, did not hesitate to leave on his alter the most precious thing they had, human and political dignity.

I am convinced that the sieve of history, sooner or later, will perform its function to give the youth of Albania today and tomorrow the opportunity to accurately recognize the deeds of their ancestors, to avoid the deception of great that we and previous generations suffered, as a result of the implementation of a political project that cost our Motherland so heavily. We must encourage this process, not because we are nostalgic for the past, but because we are supporters of the truth and because we think that in the foundations of the future of our society, there should not be fraud and malicious distortions.

The publication of this book also serves this purpose, thanks to the long, conscientious, quality and passionate work of the Marku brothers, to whom I extend my sincere thanks and warm congratulations, together with the wish that this work continues to benefit of the historical truth, of our culture, of bringing to light the national values covered by the dust of oblivion that communism deliberately threw over them for half a century. /Memorie.al

May 2006

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)