By Dr. Franco Benanti

The first part

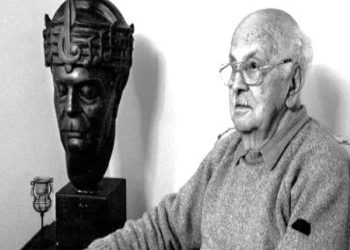

Memorie.al / The Second World War had a powerful impact on Albanian lands as well. A lot has been said about this by our historians, in the communist spirit. The generations before 1990, have learned this from textbooks, from the History of the Labor Party and the History of Albania, but very few eyes have been familiar with the alternative treatment made by non-communist historians and authors, inside and outside the country. In this regard, the book “La guerra piu lunga” by Franco Benanti, a former doctor in the Italian occupying army, in the Balkans and Albania, published by the “Mursia” house in Milan (first edition in 1966, followed by four reprints) is of great interest. later).

After September 8, 1943, when General Badoglio announced the capitulation of the Italian army and its transfer to the side of the allies, Benanti, like thousands of other soldiers, joined the Albanian partisan forces, while after the war he went through a long ordeal of internment, imprisonment and work forced, years of agony, hunger, violence, brutality, torture, until on June 30, 1948, he managed to return clandestinely to his homeland, Italy, near his wife and family.

What is shown in this book is personal testimony not only of Dr. Benanti, himself, but also of his Italian friends, with whom he shared the same fate, especially regarding the common war against the Germans and the experience of the communist regime after the war. It is interesting that although he came from a country with a totalitarian regime, such as Mussolini’s Italy, since 1922, Dr. Benanti finds more harshness and cruelty, more anti-humanism and primitiveness, in the Albanian totalitarian communist regime.

Abstracting from his subjectivism, as a member of a foreign army and a different people, as far as opinions about Albania and the events developed there are concerned, I must affirm that, as a whole, the author truthfully reflects that bitter and tragic reality , which existed in our country since the first years after the war. This applies especially to the younger generations, who have not suffered at the back of that big prison that represented the communist Albania of Enver Hoxha, for the majority of the Albanian people, to be the eyes, that that time will never return!

My mission in Albania

On a cold day in December 1941, when I was serving with the 130th Infantry Regiment of the “Perugia” Division in Dalmatia, I received orders to come to Albania to investigate areas of infectious diseases among the local population that could endanger the troops. ours there. At that time I found out about the existence of a communist movement in its beginnings and about Enver Hoxha, this news was announced by the Army Information Service (SIM).

At that time, of course, this movement had not yet created problems for our army here. Albania was more or less stretched to its natural limits, the whole country was covered by numerous constructions of roads, buildings, industrial facilities, reclamation works, etc.

Like my colleagues, I had the impression that this country was a safe haven, away from the theater of the gigantic war, which was spread in other parts of Europe and the world. I returned to Split on December 22. About two years later, the “Perugia” Division was transferred to Albania, specifically to the districts of Përmet, Këlcyra, Tepelena, Gjirokastra and Delvina. In August 1943, the situation in Albania had changed significantly. Partisan war had started.

From the four communist groups that existed before November 1941 (of Korça with Enver Hoxha, Koço Tashko, Koçi Xoxen, Nako Spiru and Mihal Lako, of Shkodra with Zef Mala, Qemal Stafa, Liri Gega, Tuk Jakova, Vasil Shanto and Kristo Themelko , of Te Rinjëve, with Anastas Lula, Elami Niman, Sadik Staveleci, Hysni Kapo, Bedri Spahiu and Ramadan Çitaku and of Zjarri, with Andrea Zisi at the head), the first three had formed the Communist Party, under the supervision and instructions of two Yugoslav communists , Dushan Mugosha and Miladin Popovic and in relation to the Comintern (the Third Communist International, which was run by Moscow).

Of the other parties, the most important was the ‘National Front’, headed by Al Këlcya, Skënder Muço, Xhem Gostivari, Hysni Dema, etc. The author apparently forgets a central figure, the founder of the “National Front”, Mit’hat Frashëri. Albanian nationalists affirmed the right to freedom of the individual, the national rights of the peoples, “Greater Albania”, echoing many layers of the population. But the cooperation between them, due to the principle of “class war”, followed by the communists, was not realized.

The Italian army had its first encounters with the partisans in March 1942, when several remote posts were attacked and several soldiers were killed. On May 1, 1942, the partisans burned the warehouses of Mavrova, about 15 km. away from Vlora, on the way to Gjirokastër. A convoy of vehicles was attacked and set on fire, a carabinieri company in Selenica was ambushed.

On July 25 (or 24?), all the country’s telephone lines were cut and the Tirana telephone exchange was set on fire. Vojo Kushi and his friends also attacked Tirana airport. In Korça, the prefecture building was burned, while in Elbasan, ammunition depots. Mehmet Shehu’s, Isa Toska’s and Alizot Demir’s squads carried out attacks on the Italian centers here almost every day.

The actions in the coastal area were accompanied by those in Central Albania, where Myslym Peza operated and in Dibër, where Haxhi Lleshi operated. The Communist Party took hegemony in the National Liberation Front, which was announced on September 16, 1942, in Peza. The Yugoslav communists continued to direct the work of the Albanian communists. Thus, after the departure of Dušan, comes Bllazho Jovanović, who organizes an extraordinary conference in Labinot, on March 17-22, 1943.

Although the Yugoslavs, among other things, demanded that he not cooperate with the nationalists, Hoxha and Dishnica (Ymer) hesitated. However, Enver Hoxha greatly appreciated “comrade Bllazho’s help that came like a deity, descended from the sky”, (this is what he discussed later at the Berat Meeting). However, they organized in August 1943, the Mukje Conference, where many important decisions were made, among which was the election of the “Committee of National Salvation”.

When Popovici and Mugosha found out about this, they, supported by Koçi Xoxe, severely criticized Hoxha, who then declared the agreement invalid, thus proving that the Communist Party of Albania was an appendage of the Yugoslav and anti-national one. Meanwhile, the fighting with the partisans intensified and our forces suffered great losses, in men and material.

The tragedy of September 1943

The coup d’état of July 25, 1943 in Rome raised hopes for an armistice and to finally return to our homes. But General Badoglio, declared that; “The war will continue”. Against whom? Would we have the Germans as allies again? Or would we fight with them?

In the Balkans, at that time, there were 700,000 Italian troops, waiting for a way to return to their homeland. In Albania there were: the fourth corps, the XXV corps, the troops of the Shkodër-Kosovo area. All of these constituted the Italian Ninth Army, which depended on the Eastern Army Group, based in Tirana. We add here other individual departments, such as the Navy, Air Force, Aeronautics, Carabinieri and Police.

The Italian forces in Albania thus consisted of six divisions, in addition to additional divisions, totaling 120,000, divided into 200 large and small units, deployed in different parts of Albania. There was also a German division, with additional units.

September 8th came, Wednesday at 19:15, when we heard on the radio about the announcement of the ceasefire. At first, we were overjoyed. The first thought was to return to our homes! Until the morning, we were waiting, asking what would happen to us, from now on. But he didn’t tell them anything else, except that; “Italian troops to be ready to react to any possible situation…”! Regarding a possible match with the Germans, we had some certainty that we would beat them, since the number of forces at that time was in our favor, 4 to 1.

About that situation, many things remained a mystery for years, until the US State Department in 1964, revealed the truth. Our troops in the Balkans made up two thirds of the Italian army at that time. We had plenty of time, beginning months ago, when the secret negotiations with the Allies had begun, to gradually retreat home.

But that didn’t happen. Because the Royal Crown and great caps had to be saved at the expense of the army, this had been the greatest concern of the General Command, from the 25th of July until the 8th of September. So, out of fear of reprisals from the Germans, Badoglio and others kept their plan a secret, to go over to the side of the allies.

The royal family, Badoglio and the major generals, abandoned Rome on September 9 and took refuge in Pescara. Meanwhile, the commander of the Ninth Army was in Rome and could not fly to Tirana. So our troops remained, not knowing how to act.

Since August 19, Roosevelt and Churchill had told Stalin that Italy would go over to their side and had given orders for the United Nations to withdraw the Italian soldiers by ship to the coast, to Italy. While Badoglio, “this real soldier”, who after his death also erected a monument, spent 45 days, without notifying anyone, due to his fear of the Germans.

In the entire Balkans, there were no more than eight German divisions, three in Dalmatia and five in Albania and Greece. So the Germans felt weak, they sought in the first moments some kind of compromise, to resolve the situation and not to use force. To this day, the drama of the Italian divisions in Albania and the cost of their losses has not been sufficiently well known.

On September 9, 1943, the Germans introduced the 181st armored division into Albania, which took over our outposts in Shkodër and Lezhë. The 92nd Motorized Regiment was deployed in Durrës and Vlora. On September 10, the 100th infantry division surrounded Tirana, took the Army command post, the Autopark and barracks, offices and military warehouses. The Germans captured the commander of the Eastern Army Group, Ezio Rossi, who had come to talk with them. The commander of the 9th Army, Renzo Dalmazzo, was forced by the Germans to order the disarmament of his army.

In these conditions, many Italian soldiers and officers refused to lay down their weapons and joined the ranks of the Albanian partisans, others were captured and mistreated by the Germans (they were killed on the spot, sent to concentration camps in Germany, or were put into forced labor).

My own unit was captured by the Germans and ordered to march towards Vlora, to leave from there for Germany. In Mavrovo, taking advantage of the circumstances, together with others, I escaped and went to the mountains for the district, where the partisan forces were operating, with which I joined. As a doctor, I was assigned to work in the partisan hospital of Smokthina. The conditions there were extremely poor. The wounded were kept lying on the ground, in deplorable hygienic conditions and in great disorder.

In addition to two Italian colleagues, Dr. Ibrahim Dervishi, helped by a student named Lume. (Actually, her real name was Drita Kosturi, ex-fiancée of Qemal Stafa). I asked them if I could also look at the wounded Italian soldiers, who had been placed in a tent. Even these five soldiers of the “Perugia” Division were lying on the ground. They were starving. They died the first night and were buried somewhere, near the river Shushica.

After a few days, we moved to Kudrevica mountain, about 2000 m. above sea level, because the Germans were approaching. We stayed there for a few days and then returned to Smokthina, after the wave of German reprisals passed. Disarmed by the Germans, on the march towards the Macedonian border, about four hundred Italian soldiers were captured by the partisans, stripped of their clothes and shoes and taken to the labor camp in Punemira, near Voskopoja.

The camp commissar was a sadistic criminal who treated the Italians much like the Nazis in their concentration camps. Italian soldiers and officers, half naked, lived in barracks without doors, about 1500 m. above sea level, where the temperature during the day went below zero, while at night, up to minus 15 degrees Celsius. They were fed with 300 grams of corn bread a day and nothing else.

In spite of these conditions, they worked all day, without interruption.. Deforesting, making firewood, carrying materials on their backs from Voskopoja to Punemira. Whoever returned late did not receive the bread ration. Many prisoners suffered from malarial fever, calluses on their feet, without receiving any medication. Some died of dysentery, or exhaustion. Whoever did not fulfill the norm was severely punished.

Once, when there was an attack by the Germans and the partisans fled, the group of Italians marched to the coast, hoping not to capture any ships bound for Italy. Very few eyes reached the coast, while others either died on the way, or were captured by villagers, who took them home to do work for a piece of bread.

The help of the Italians in the liberation war

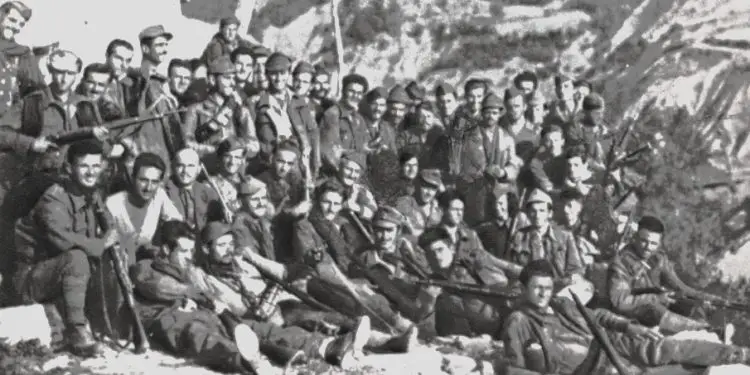

As I said, many Italians joined the partisans and fought heroically. They even formed special units, such as the “Tomorri” and “Antonio Gramshi” battalions. Partisan commanders, such as Riza Kodheli and Mehmet Shehu, testify to this, in the composition of whose wards even teams or entire companies operated, with artillerymen and Italian military specialists.

The “Antonio Gramshi” battalion, although it bore the name of a well-known Italian communist, was formed only by Italian soldiers, with different ideological convictions, but with a common sense of freedom and justice. We are mentioning one case: the attack on a German convoy on the Elbasan – Peqin road where 18 vehicles were destroyed, 28,000 kg of bombs were thrown, two German planes were shot down and 54 Germans were killed. To be mentioned are the battles in Zagori in January 1944 where 11 Italians lost their lives, with Terzilio Cardinali in charge.

The German Winter Operation, 1943-1944

In this operation, the Germans committed five of their divisions in Albania, Greece and Yugoslavia, plus some special units and collaborationist forces. The partisans had about 20,000 fighters, in four brigades, nine groups and 18 battalions, including the “Antonio Gramshi” battalion. These received help in weapons, clothing and medicine from the allies. The English had about 30 of their advisers near the partisan brigades, where, among other things, they also had eight radio stations. But they were treated by the partisans as potential enemies, encouraged by the Yugoslav envoy, Svetozar Vukmanović Tempo, and therefore under strict surveillance.

After four days of heavy fighting in the area of Arbana, near Tirana, the partisans retreated to the area of Cermenika. There were many killed and wounded. The rules were so strict that those who could not follow the convoy were killed with a bullet in the neck. With these measures, Mehmet Shehu managed to save his Brigade from disbanding, despite Beqir Balluku’s Second Brigade, which was completely destroyed (killed or deserted en masse). The Germans launched a second offensive on January 7, when the first brigade had withdrawn below Shkumbin, the second and third had been destroyed and the General Command was isolated and unable to function.

Vermiku Hospital, near Smokthina

It was a house of the peasant Riza Luna, which was put at the service of the sick and wounded. Partizan Ylvie was in charge of the hospital. Some partisans of the 5th Brigade, which operated there first, took care of the protection and services at the hospital. Ylvia was around 30 years old, married to a partisan of a brigade operating in Dibër, named Skënder. He dressed with some elegance and kept to himself. He hated Italians, but he was fair to me.

In February, Ibrahim Dervishi and Ylvie’s husband came to Vermik. They brought an order for the transfer of my Italian colleague, Condrell, somewhere on the Macedonian border and fled again.A few days later, Ylvija fell deeply in love with Braho Kuči, the commander of the hospital’s armed guards. But after a while, she grew cold with Braho and began to make love to any man who passed by, even the sick. Her case made me understand how the feelings of free love explode, even in the harsh conditions of war. Memorie.al

(Translated from Italian, Bardhyl Selimi)