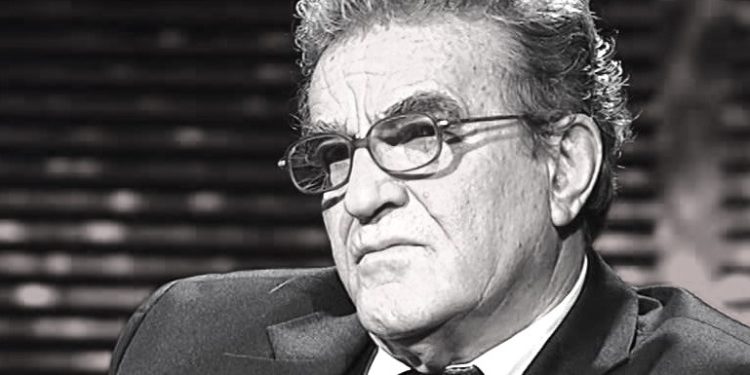

By Dr. Uran Butka

Memorie.al / “A letter (the content of which we must not only feel, but also savor) is for me a luxury, a delight of the mind; and luxury requires leisure, calmness, and an undisturbed atmosphere. Hurried luxury degenerates into the grotesque. Go and see the American city, Atlantic City, where the insolence of a rapid luxury creates such a great contrast with the European beauties of the 17th-18th centuries” — Mid’hat Frashëri.

The correspondence of Mid’hat Frashëri constitutes the crown of his meditation, his writing activity, and his creativity: therein appear his new Enlightenment ideas in every field of life and thought, his challenges and decision-making at key events in the nation’s history, Albanism as a platform and action, titanic efforts in defense of the Albanian cause in crisis, tireless persistence for its most positive resolution, humanism and Europeanization as a spirit and model, diplomacy as a craft and art, debate with irrefutable arguments and logic, eloquence and noble conduct, conversation and polemics with prominent Albanian and foreign historical personalities—including heads of state, prime ministers, ministers, chairmen of national and international forums—national cooperation and unity, Albanian Haxhiqamilism, the communist threat, the struggle for the rule of law and democracy, friendship and love, but also existential criticism, foresight, superior culture, broad information, and the official, yet intimate and artistic sense of this correspondence.

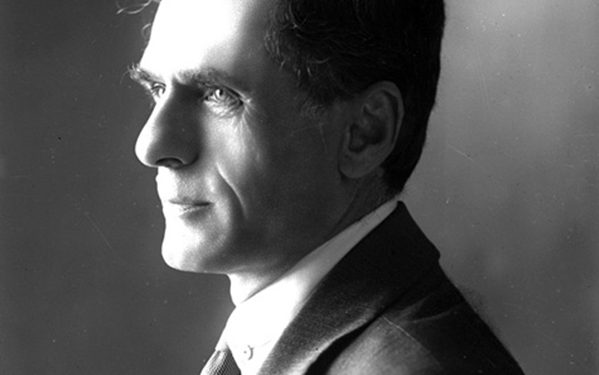

There are three peaks of this epistolary wealth: the period when he was a member and chairman of the Albanian delegation at the Paris Peace Conference and the League of Nations in Geneva, defending Albania’s identity and territorial integrity against Serbian, Greek, and Italian expansionist policies, but also against the imperialist policies of the Great Powers often supporting them, as well as in defense of the Albanian population of Kosovo and South-Eastern Albania, unjustly occupied and persecuted to the point of annihilation;

The correspondence while he was Albania’s ambassador to Greece, where he defended the Cham cause like no one else, confronting the anti-Albanian and anti-human policies of Hellenism regarding the barbaric displacement and expropriation of the Albanian population from their lands in the years 1923-1925; and the erotic correspondence, which lasted almost his entire life, just as his love did.

Mid’hat Frashëri’s love was an eternal ember, covered with the ash of life. He stirs and rekindles the coals with his feather-pen, glowing in a green light, masterfully and artistically pouring them into his letters. His love is sincere, spontaneous, magical, and emotional.

He experienced it with passion more than once, as a free and cultured man—that unalienable internal human sensation, that burning and tearing ember, like light and darkness, like joy and suffering, like poetry and drama, like a human force that liberates and changes the world.

“Love,” he writes, “is the condition of life. If it does not exist, the bond between the limbs of man, the family, and humanity is destroyed; the taste of vitality and life vanishes. Without love, there is no enthusiasm, there is no hope, no deed is accomplished. Enthusiasm and hope, the daughters of sincere and deep love, must be like those morning roses that bloom anew every day, like those flowers that close at night but open under the first rays of the sun.”

The love letters between the Romanian intellectual Angela Romano and Mid’hat spanned and were documented for 24 consecutive years—slightly longer than the love letters between Balzac and Princess Hanska—but also with an indescribable pathos. To the question of why Mid’hat Frashëri never married, his letters and those of his beloveds provide the answer.

Consumed by longing and distance, Angela Romano invites her lover to Bucharest, where she had all the comforts to live together with “her idol, her unrealizable hope,” as she expresses in a letter. But Mid’hat chooses between Angela and Albania, opting for the latter, and she replies: “I am happy for you and for your country.”

Mid’hat responds to his beloved Emma: “You know the moral illness from which I suffer—that mania for analyzing things, that urge to always dig into their depths, wanting to see far ahead, very often considering the present as a preoccupation for the future. A marriage, for me, is impossible, and I am certain that I would never make her happy.”

In a letter to Elsa, Mid’hat wrote: “I want you to be happy, Elsa. I am struggling between heart and reason, between love and duty, precisely in the name of this love.” Elsa replied: “Perhaps it is a great madness, my love for you, who loves freedom so much—to travel, to go around the world, who desires change, a life without troubles, without worries.”

Mid’hat was a free European citizen; thus, he strove, not without dilemmas, to ensure that passion and family life would not hinder his great love for the fatherland and his duty to the national cause, nor would they hurt his loved ones.

Mid’hat maintained an extraordinary correspondence, not only in its dense content but also in the sheer quantity of letters, which reach into the thousands upon thousands. It is astonishing where he found the time to write endless letters, considering his highly intensive patriotic, political, diplomatic, pedagogical, cultural, research, Albanological, critical, publishing, literary, memorial, and bibliographic activities, alongside descriptions of travels within and outside Albania.

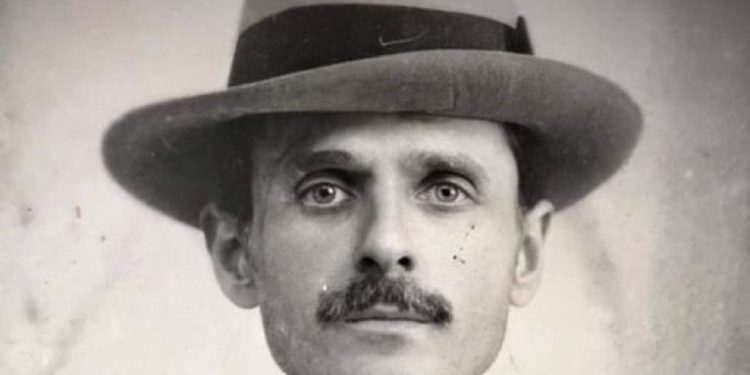

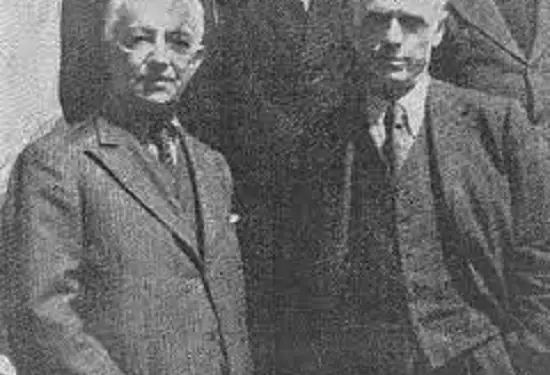

He wrote and exchanged letters out of the necessity of the time with personalities, but also simple people of the Albanian world, such as: Ismail Qemali, Luigj Gurakuqi, Faik Konica, Mehmet Konica, Kristo Luarasi, Gaetano Petrota, Dr. Ibrahim Temo, Dr. Mihal Turtulli, Fan Noli, Sulejman Delvina, Shtjefën Gjeçovi, Gjergj Fishta, Gjergj Pekmezi, Ahmet Zogu, Sotir Kolea, Rexhep Mitrovica, Bedri Pejani, Dhimitër Berati, Aqif Pashë Elbasani, Eshref Frashëri, Pandeli Evangjeli, Arif Dino, Asdreni, Kolë Tromara, Kostë Çekrezi, Mihal Grameno, Avni Ru1stemi, Samin Visoka, Branko Merxhani, Mirash Ivanaj, Seit Kemal, Hil Mosi, Kolë Kamsi, 2Karl Gurakuqi, Musine Kokalari, Emine Frashëri, Abaz Kupi, Dhimitër Falo, Safet Butka, 3Sali Mani, etc.;4

But also with prominent personalities of world p5olitics and diplomacy, such as President Wilson, Lord Robert Cecil (Chairman of the Paris Peace Conference), Jules Cambon (Chairman of the Conference of Ambassadors), Eric Drummond (Secretary-General of the League of Nations), D’Estournelles de Constant, Lloyd George, Aristide Briand, Aubrey Herbert, Edith Durham, Justin Godart, Baron Hayashi, Telford Erickson, Jean Pelissier, I. S. Barnes, Morton Eden, A. J. Balfour, Rene Viviani, K. Ishii, Bill McLean, Alexander Kirk, Julian Amery, etc., as well as ministers, deputies, advisors, ambassadors, writers, editors-in-chief of agencies, newspapers, and magazines—friends and foes of Albania and Mid’hat Frashëri.

Likewise, he corresponded with personalities of European science such as: M. Šufflay, G. Weigand, E. Pittard, M. Roques, M. Tomasic, H. Pedersen, N. Jokl, Prof. Meillet, E. Legrand, etc. The correspondence was researched and extracted from the Central State Archive, the Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the archives and libraries of Turkey, France, Great Britain, the USA, Greece, Romania, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Germany, Italy, etc., mainly in Albanian, French, and English. This correspondence is encompassed in volumes VI and VII of the “Mid’hat Frashëri” series. / Memorie.al