By Ahmet Bushati

Part twenty-nine

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Shkodra in the first years under communism

We found the door of dungeon no. 9, which faced the dark side, half-open and a corporal named Ismail with clenched fingers on one hand, as soon as he entered, said to me coldly: “Hand over whatever you have with you”! and I took from my pockets a gray fountain pen, a five-ALL metal note – which, although it didn’t buy anything, I had been keeping for a few days – an empty wallet and a Russian dictation sheet that we had developed in class a few days ago and that the good Russian teacher, Nina Yevgenia, had returned to us to correct during the break between the first and second hours of that day.

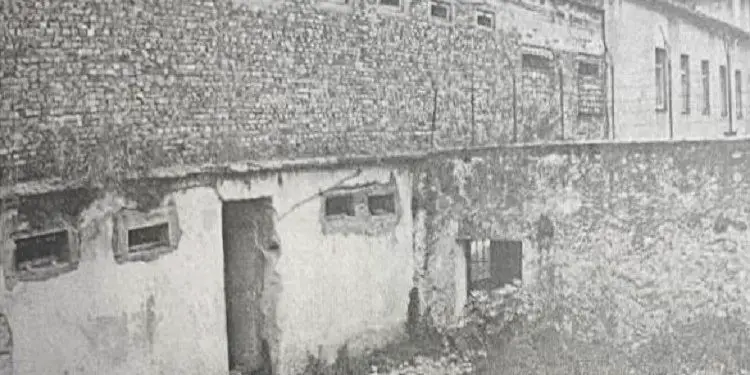

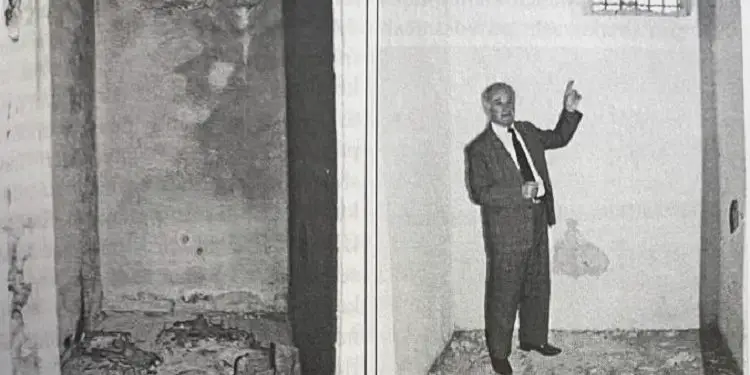

The corporal, cold and serious in his work, as he put me in the dungeon, automatically locked the door and left, forgetting to turn off the light, so I, taking advantage of his mistake, began to inspect that dungeon measuring about 2.2 x 1.4 m. and in the meantime I was thinking sadly about the many innocent people who must have passed through it, and perhaps there were also human lives that had been lost there. My first impression was that that dungeon seemed very small and too closed for a human life and a cold feeling of loneliness and abandonment, as if he told me that that dungeon and nothing else would be my fate for who knows how long.

Once upon a time, before we were fully grown, we were deeply impressed and captivated by Silvio Pellico’s prisons, the stone cells in the novel “The Bridge of Sighs”, the hero Tosca himself in the film “La donna e mobile”. Heroes from the “Independence Movement”, from the “Mountain Flute”, “those who fell” during the war and afterwards, those of the “resistance in the “mountains” and “Security”, would be those inseparable models of our imagination, who, so to speak, would pave the way for us to walk. So, when we were put in prison, we would have taken the best aspects of what life had brought us up to that point, and now it would be our turn to test ourselves.

The prisoner, having just found himself alone inside such a cell, immediately began to investigate the environment there with curiosity, – no matter how small and completely closed – trying to find any traces of life of his predecessors. Thus, at first, I would be impressed by the sight of three or four strands of human hair stuck to the wall, He gathered them like a tube and mixed them with the whitened plaster dust, so that they could hardly be distinguished as human hair. How many sad thoughts enter the young prisoner in contact with traces of such lives!

It suddenly occurs to him that those hairs could belong to some prisoner who was drowned there under torture; or the hairs of another, who was worried about his family, or perhaps he could not stand the torture, had once surrendered to the interrogator, and later, repenting and killing his conscience for that, had pulled out the hairs of his head. He also thinks of a prisoner who could have been crazy there, as well as of how many other cases a young prisoner is able to imagine!

Below one wall, two carefully carved initials P. P., would make me painfully believe that they were not by the hand of the late lawyer Paulin Palit, shot a few days earlier. It wasn’t long before I felt tired from the unusual events of that long day and sat down to rest there on the black cement with large damp spots.

The light was quickly turned off and I found myself immersed even more in silence and isolation, making the hours after lunch, although few, never pass. Today I can’t know why I was thinking about them so much at that time, but I remember very well the effort I made to put the people at home out of my mind, as the only thing that could weaken my will to endure, no matter how encouraging my father’s attitude of the previous night remained for me.

Shortly after it was dark outside, I suddenly heard a muffled, muffled noise, something indefinable, perhaps like the running of people in tights, which was repeated continuously at short intervals. The deep silence that reigned in that prison, the absence of a human voice or any sign of life, made one think of the most suspicious things.

Curiosity pushed me to approach the dungeon door, where I saw that fortunately, between the tightly sealed door and its frame, a narrow, vertical gap had opened, a millimeter-sized space of light that allowed me to watch in the corridor how that corporal with the sharp fingers of one hand, after locking the door of a prisoner who was returning from the W.C. with an empty suitcase in his hand, opened the door for another, who also ran with a full suitcase in his hand, headed for the W.C., and so on, until finally that corporal opened my door too, speaking to me fiercely:

“Come on, go to the toilet”! and since I wasn’t running, he gave me a light push on the back, which, as if insulted, made me turn my head back and even stop for a moment, but when I saw that the corporal was advancing towards me, I continued like those I had seen through the hole in the door of the dungeon.

That night, as on several other days and nights, investigator Siri Çarçani would regularly call me twice a day and keep me in his office for a long time, constantly threatening me with the consequences that would happen if I didn’t change my mind. He, as he was sent by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, enjoyed great authority among the other employees of the Branch. Since those first days, I had the opportunity to see how those ignorant and servile employees of the Sigurimi, in his presence, remained silent and never took their eyes off him.

Thus, e.g., if he, with his serious appearance and without looking them in the eye, would ask for a letter in the hope of starting the process with me or Gypsies, in an instant, from more than one direction, they would be hastily served on the table. The inferiority complex that at that time – as we have said – generally characterized the Shkodra communists in front of those from the south, due to the greater trust that the Party had in them, was also manifested in the Security.

The truth was that during those days he had not touched me at all with his hand, but the days and nights that I was spending were tightly bound in chains, without food and without clothes, sleeping, when it was winter, must undoubtedly have been his orders, not to mention his cunning and arrogance, which would also be so unbearable. “You should know well that we will extract even your mother’s milk if you don’t speak”! He would say to me several times during those days. After four or five days had passed, he temporarily gave up on me.

Surprised by his always harsh behavior towards me, I would have seriously asked myself dozens and dozens of times whether that man, although he came into life with obvious inhuman tendencies, would it be possible for him to behave differently outside that Sigurimi building, that is, with free people, like people in general among them? Does this man have a wife? Does he have children? If “yes”, will this person, like all other people, know how to address you with a smile and “love you”?

The questions I would ask myself would be of the most diverse and naive kind, and who knows how many times I would have thought to myself: “Well, friends did this man has it”? And also, “what would have pushed that friend of his to approach this man”?! etc., etc., questions that I would ask myself every time I returned to the dungeon after an interrogation session I had with him, in which, “the man and the investigator”, were written in a single thing, which only a Sigurimi had managed to find and combine to adapt to his criminal work!

Since the second day after my arrest, when I went out to the W.C. I would look at the end of the corridor, one of those thick woolen mattresses that my family had brought me, but to get me into the cell, they would have liked me to spend a few more good days. Likewise, somewhere near the guard’s duty station, I had noticed day after day a pretty white safe with the label “Ahmet Bushati” on it, which would not allow me to stay as long as the mattress.

During the first two weeks, as food, they would give me only a piece of black bread for lunch, accompanied by a large glass of ice water. My hands were constantly handcuffed and tightly clenched. To sleep, I slept as I was, with my clothes on, clenched into fists on the cement and shivering incessantly from the great cold I was in.

The prison itself, although they closed and buried it as part of a real hell, could not It is said that there is no life at all, very few lives of people trapped in prisons who day and night think about their families, as well as about the fate of their lives and honor, called into question by physical torture and numerous psychological pressures that an investigator, as ignorant and devilish as he is a criminal, constantly exerts on them, who has linked the fate of his career to the success of his work on the victim he was given to investigate.

For the prisoner under investigation, even the idea of being called up to the investigator’s office is a real torture. The investigator insistently demands that the prisoner confess to those charges that are of interest to the purpose of a certain process, something for which the prisoner remains and thinks inside the prison, formulating answers to every possible question of the investigator.

The cases, depending on the degree of torture and the character of the prisoner, vary from one prisoner to another, starting from those who would resist until they were left to die in the hands of their interrogators, to those who had obeyed the fearsome interrogators from the first or second day, and who had agreed to sign a trial with the most absurd accusations both for themselves and for their friends and comrades. Of course, there would be another category of prisoners who, in order not to be ashamed, would also ask for death, but if they could not do so without being subjected to torture, they would agree to undergo the trial under the dictation of the interrogator.

During those first days, from that gap in the door, I saw and recognized Ruzhdi Çoba, the professor who had taught us history until two months ago. There were also former students of the American Harry Fultz, who were accused of alleged espionage in the service of the C.I.A., whose names I would learn later, and who would be: Xheladin Baci, Lec Barbullushi, Ruzhdi Baja, as well as Qazim Dervishi, my former childhood teacher, whom I did not recognize due to the tortures they had inflicted on him.

There was also the Italian priest, Father Gardini, – with whom two years later we would be in the same prison cell and later in the camp – who at this time I was watching constantly pass through the corridor with his head hanging to one side, perhaps as a sign of his priestly frustration. There was also another priest, quite old, who walked slowly and carefully with small steps like a child, since the sufferings of prison were temporary for him, as he was probably over ninety years old at the time. Also there was a kind of civilian-dressed imam there at that time, a blind man named Riza Mani, who walked shaking his head from side to side.

There, summoned for detailed explanations, the convicts Adile Boletini, Drita Kosturi, Agime Pipa and Terezina Pali would also be there. After the first four or five days, from dungeon number 9, they moved me to the other side of the corridor, to dungeon number 17, which always fell from the dark side. Changing from one cell to another is a very unpleasant experience for a prisoner accustomed to any of the previous ones. In this second cell, I would no longer have that narrow gap of light in the door as in cell no. 9.

The “quarantine” continued: I was constantly shackled, with only a piece of dry bread that the policeman threw to me from the window like a dog at lunchtime, and always without sleeping clothes, which meant that I would spend the whole time huddled against a corner of the wall, shivering incessantly from a cold that had penetrated my very core.

During this time, I would be regularly interrogated twice a day by an investigator from Dibra e Madhe with the rank of second lieutenant, who, having trusted my hands, which were very tight from the handcuffs, hunger, the cold of winter and wet cement, as well as my increasing physical weakness, seemed to me to be expecting my surrender from one day to the next.

The tactics of the investigator are well known, who, in order to ensure as much space as possible for the investigation, will not let you die, unless he has obtained from you, as a prisoner, the statements that the purpose of a trial requires. So, after about two weeks in the second dungeon, my hands were untied for the first time and for the first time they brought me sleeping bags, as well as food, which impressed me greatly when I saw them, as they were plentiful and of a standard that had been broken in our house for three years.

From one day to the next, I began to recover, and the interrogator would generally take me easy. The days were cold, but sunny, which I understood from the corridor that was more illuminated and which, by reflex, allowed very little light to enter my dark dungeon. On such days, let’s call them “days of light”, I would lie down as I would, dozens and dozens of times, count the sixteen narrow planks of the high ceiling above my head, placed transversely on two wide steel rails. Just as many times on a good day, I would also count the three rows of iron squares above the door, which were supposed to serve as windows for the dungeon.

Sunday, as a day of rest, was also reflected in our prison: there were no police movements and usually no interrogations of prisoners. The silence was deeper than that, as if from a real grave, as if it numbed all internal energy.

So on a Sunday morning, when no movement or sound was heard inside or outside our prison, suddenly a deep voice broke out, the man who shouted loudly and quickly: “Allah, Allah, Allah”! not to stop for several minutes in a row, until he was taken out of the dungeon with his last breaths, but without anyone noticing then or later who that man was and whether he had died or not?!

But the strangest thing about that day would be that, as if for a peak of contrast, at the very time that man was praying to God on the verge of death, by coincidence and as if by irony of fate, somewhere in a house near our prison, the joyful dance of many wedding guests, men and women together, would suddenly break out, “The bridegroom has come to take the bride”!

It was during this time that for several days, especially at night, I had been hearing the groans of a prisoner, who, as far as I could tell, was trying to contain them, but without fully succeeding. After a few days, in the distorted timbre of his voice, I would recognize Xhevat, who had been arrested about three weeks before me. I waited for the guard to move to the other end of the corridor, and then, as soon as I heard him speak, I called out: “Xhevat, is that you?” “Yes,” Xhevat answered.

“What’s the matter?” I asked again, and Xhevat did not answer me or listen to me, not ever. Perhaps my intervention somehow offended his delicate nature. I myself was also left feeling bad, very bad, thinking that, although unintentionally, I might have hurt my close friend in some way, in whose strength I would continue to have unwavering faith. Memorie.al