Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al publishes some excerpts from the memoirs of the former British soldier, Julian Amery, who was on a mission in Albania in 1941 – ’44, who in 1947 published in London the memoir book “Sons of Albania”, where he describes in detail all the reports and relations of the British missionaries with the communists of Enver Hoxha and why they left their friends in the mud, led by Abaz Kupin!? In addition to the events of that time, Amery, has described in detail many of the portraits and main actors of that war, such as Abaz Kupi, Prenk Përvizi, Muharrem Bajraktari, brothers Kryeziu, Llazar Fundo, Mithat Frashëri, Gjon Marka Gjoni, and up to the head of Albanian partisans, Enver Hoxha. The book “Sons of Albania” by Julian Amery, was translated in the early 1950s by Felatun Vila, who at the time was serving a sentence as a political prisoner in the forced labor camps of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha in Albania and was published before a few years in Albania by the family of Abaz Kupi living in the US and that of Hasan Dosti in Albania.

Given the great distortions, falsifications and manipulations that Albanian historiography underwent during the years of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha and in particular that which includes the period of the Anti-Fascist War in 1939-1944, the publications of foreign authors at that time have constantly aroused interest. extraordinary. Among the foreign authors who have published memoirs and analyzes of events belonging to that period are former Anglo-American military missionaries, who were themselves witnesses and key actors in the major events of that time, such as Peter. Kemp, David Smajl, Reinald Hibert et al.

Some of their books that have been translated and published in Albania, have aroused much interest and have been quite sought after, for the realistic reflection of events that capture one of the most discussed periods in the entire history of Albania. One of those publications is the book “Sons of Albania” by the former British soldier, Julian Ameru, who together with the above-mentioned authors, Kemp, Smajl and Hibert, during the years 1943-1944 was himself on a mission in Albania. That book was written by him based on records kept during that time and was originally published in London in 1947, shortly after the end of the War.

In his book, the British Julian Amery, not only testifies to the events where he was an eyewitness himself, but he takes a brief look, analyzing the events that mark an earlier period in the history of Albania, since the period of Roman occupation, the period of Turkey, the First World War, the reign of Ahmet Zogu, and even the factors that led to the occupation of our country by fascist Italy. While the events that cover this period of time, almost 500 years, do not occupy much place in the book, those of the years of the Antifascist War 1939-1944 occupy the main part and are described in detail by the author.

In addition to the events of that time, Amery has described in detail many of the portraits and main actors of that war, such as Abaz Kupi, Prenk Përvizi, Muharrem Bajraktari, the Kryeziu brothers, Llazar Fundo, Mithat Frashëri, Gjon Marka Gjoni, and even the head of Albanian partisans, Enver Hoxha. The book “Sons of Albania” by Julian Amery, was translated in the early 1950s by Felatun Vila, who at the time was serving a sentence as a political prisoner in the forced labor camps of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha in Albania.

But, that work translated by him of course could never see the light of publication at that time and the book was archived in the archives of the Ministry of Interior, after its translation, by the communist regime, was done to see what was written in address of the senior communist leadership of the wartime period. The book “Sons of Albania” was published only four years ago, under the care and sponsorship of the family of Abaz Kupi who lived in the US and that of Hasan Dosti, who lives in Albania. Also, from this book (equipped with numerous photos of that time) that was published in English, being distributed in the US and Britain, Memorie.al has selected several parts, which describe the tragic fate of Albanian nationalism in end of the war.

Memoirs of former British soldier Julian Amery

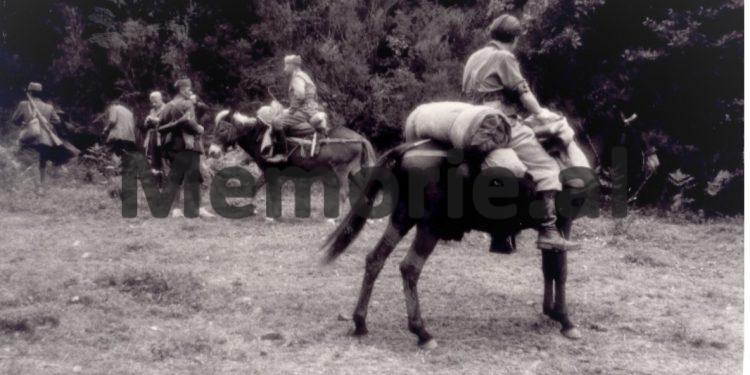

The refusal of the British command to evacuate Abaz Kup with our mission, was a severe blow to his pride. But he understood our shame and was moved by our decision to flee with him, rather than leave on an English ship. “It’s better that way,” he said with typical generosity, “because it is my duty as a man to whom I have promised to accompany you until you leave safely.” That same afternoon, he sent agents to Durres and Shkodra to find a boat. We stayed two weeks on Mount Vela waiting for news about the boat. Meanwhile Agai had decided with whom he would leave. He had chosen Petrit, his eldest son, and Rustem, his youngest. Also, Gaqo Gogon, who would serve as secretary, and Ramiz as a bodyguard. There may not have been room for more people in the boat, so he left his wife, daughters and remaining son in the care of his friends near Shkodra. The weather was already bad and the first snow whitened the mountains. The days passed more slowly because it was very cold and damp, which made it impossible to stay outside. But even inside the house it was too dark to read. So, we slept, talked or spent time among the Turkmen. October was the time when rakia was roasted and sometimes we wandered to see the villagers boiling and plums in their primitive cauldrons. Meanwhile Smiley made one last observation of the coast, jumping so far north that it reached as far as Shengjin, the ancient mooring place of San Giovanni di Medua. One day the Germans, who had felt our presence in a place so close to the road, sent a patrol to uproot us from Mount Vela. Abducted by their approach, Agai grabbed his rifle and went out to confront him. We rushed after him together with the Albanians and Turkomans taking a defensive position on the ridge of a hill below the church. The land in front of us was wooded but as we watched the Germans advance through the trees, Agai told the people not to open fire. As they approached very close he shouted loudly and joint volleys erupted through the branches. The Germans at first hesitated then when the guerrillas started firing one by one, they turned back and fled so as not to be seen again. On October 4 a telegram came from our General Quarter, announcing that the next night a boat would be sent to pick up the Nile along with its mission. At the same time, we were suggested to board too, but the absence of Smile, who was under surveillance gave us a suitable pretext to reject the plan. Nili left with a number of Turkmen deserters, some Italians staying with us in the camp and two Albanians. Meanwhile, in a tragic accident, the radio telegraph operator, Captain Baten, was drowned by the floods of one of the portable bubbles with which the passengers reached the torpedo boat. Haberdajni, Nili’s deputy, remained in Shkodra, as being very ill he could not move. He had been instructed to accomplish our mission as soon as he was healed. Meanwhile, the partisans continued to advance in the North, while we decided to wait for Aga’s boat in the coastal lowland beyond Lezha.

Cup effort to find the boat

Our forces consisted of almost a hundred braves of Abbas Kup and dozens of Turkmen, Albanians and Italians. Protected by these few loyalists we were confined to an area of five square kilometers, bordered on the north by the Drini, on the south by Mati, on the east by the main road, and on the west by the Adriatic. The Germans and partisans surrounded us from the ground and although the swamps and canals gave us some hope, the only line of our retreat was through the sea. Our enemies were still reluctant to pursue us in this swampy area, but we knew this rest was short. The Germans did not feel comfortable, from our presence on the other side, while Enver Hoxha had decided to stop Aga’s escape. Agai’s agents had not yet found the boat, but Ihsani told us he was in contact with a ship’s captain, who agreed to make the voyage for a hundred napoleons of gold. Our funds were exhausted, but Abas Kupi had as much money as needed, so Ihsani went to Shkodra with Petrit to finish the bargain. A few days passed, and Ihsan returned with the sad news that the matrapaz captain was now demanding a higher price. Agai was unable to meet this new demand, but our host, hearing the plight, agreed to mortgage his land to secure the necessary amount. Ihsani returned to Shkodra and the next day informed us through Petrit that he had found a more honest sailor, a Montenegrin, who was ready to take them in an open boat. That night Smiley wrote in his diary: “Everything is arranged except where we are going, dates and signals!”

The last hours before departure

The weather was beautiful on the coast, but October is malaria season, and our nights, were troubled by countless mosquitoes. Quinine reserves were depleted in time, but fortunately we did not catch a fever. They wreaked havoc on our Turkmen and Albanians. At first, we spent the day outside, relaxing on the brightly colored carpets, which our host laid out especially for us in the sunshine. Then came the rains, which transformed the land into a swamp while a cold wind coming from the north forced us to always stay home. The extension of our visit reduced the food resources in that country. Supplies began to become rarer and instead of the old brandy we were initially greeted with, they now sold us a more bitter drink. From time to time, in search of good news or food, we visited nearby villages. Whereas when the evenings were beautiful, we walked through the camp to see the Turkmen dancing around the fires and listening to their wild and wailing songs. Now it got dark quickly, and we started playing chess, games in which Agai openly cheated like Napoleon. So, ten days passed, waiting for the boat. Meanwhile, the Germans had withdrawn from southern Albania. Although they still held Tirana by means of a strong garrison, the general staff of the corps was transferred to Shkodra. The Albanian government had collapsed, some of the ministers had followed the German generals while others had remained in the capital, or were looking for unsafe, some shelter in Durrës. The partisans advanced like a great wave in the footsteps of the German army, while the Albanians succumbed to the enthusiastic communist government. A German defeat was good news in any circumstance, but the change of bosses seemed to be a dubious victory for the Albanians. As for us, we could only feel a meal of joy from such a victory, which placed the Strait of Otranto under Russian influence. However, our superiors in the General Quarter still seemed to believe that Enver Hoxha was their friend, so they summarized the policy. Fear had gripped the entire camp in those last days, but Abas Kupi remained calm until the end. His kindness towards us never ran out and he, under no circumstances showed in words or deeds any sign of anger towards the treatment of the British command. Agai had realized that we were his friends and always spoke by saying “our defeat” identifying us with his cause. We had been able to get to know him well during these seven months, in which we had so often eaten bread together and slept under the same roof. Our respect was added by recognizing Him Again in intimacy. No one could be sober from morning till night, but Abas Kupi had a leadership force, a natural wisdom and a generous character which withstood the test of a daily toil. Courage, cunning, energy and patience are necessary qualities for a guerrilla leader. But Abbas Kupi’s special genius lay in his mastery of engaging people in tasks as well as in his natural pragmatism. He knew exactly how long a man’s service could be worth, and he summarized in fine art the methods by which he used others for his own purposes. He would appeal with an almost feminine intuition to the strongest or weakest feelings of each individual, and his technique in these matters was very personal. Agai would always talk face to face with people. Rarely believing he could only be betrayed. But if doubt prevented him from delegating his authority, the actions stood out perhaps more, in that he himself, was the spirit of feelings of weakness. He understood by intuition and judged only after the results and, in fact often times seemed to us to be deaf to the arguments and blind to the intentions of others. Such objectivity was also a test against the sentimental calls of a demagogue, the scrupulous reluctance of a moralist, or the elaborate disagreements of professional politicians. This was perhaps the real secret of his power. This explained the fact that an uneducated man could gain the support of intellectuals and destroy in four years, the devils of a Mustafa Kruje, or the secret intentions of the missionaries of the Comintern. Ultimately, my account comes from some act of trustworthiness, and belief in British power was Agate’s leadership for action. The desperate situation may have suggested he was wrong; however, he still believed his defeat was a temporary bad game.

The departure of the British without the Cup!

Our road from the forest led us through swamps and a wide lagoon, where the water reached up to my horse’s hoof. At first the silence of the night was broken only by the sound of crackling. But after a while, we began to notice the murmur of the sea waves, which crashed gently on the sandy shore. Across the lagoon we climbed a dune and, carefully clearing the way, through a German minefield, descended to the coast. The sea was calm as a lake and above the horizon, hung below, the full moon. A German bunker was located two kilometers to the north, but we believed that the garrison was too demoralized and would not fall on our necks. When the moon fell, we lit a bush fire and, wrapped in hoods, sat down to wait for the ship to arrive. It must have been two hours and I was no longer trying to see through the darkness when McLean showed me a black shadow in the sea. It looked like it was about ninety feet away and I was surprised I had not noticed it before. A smaller shadow quickly detached from it, and as the waves pushed it toward the shore, we saw that it was a flat-bottomed landing craft. Two sailors and a young officer were working on the oars, and he came down and greeted us. He belonged to the “security” and was sent specifically to make sure that we would not take Abas Kupin with us. I said goodbye to Shaqiri and Haliti, while to the faithful Kolaver I handed the horse with the saddles of the saddle as well as a handful of gold. This withered and slippery cub kissed my cheeks, hands and burst into tears like a child. I boarded the landing boat with Haberdajin and two Russians while the Albanians pushed us with the shouts “Hello”. After a few minutes we were near a MAS gas station run by an Italian crew. Ivan helped me climb the deck and sat down in despair on a pile of ropes. The ship was not comfortable and there was nothing special. It resembled the plane from which we had jumped eight months earlier. The sailors again gave way to oars towards the coast and soon returned with McLean, Davis and the other Russians. When we had boarded all the landing craft climbed by crane the side of the ship. Then the engines started and the ship slid quietly across the sea. After we left Cape Rodon, the captain ordered us to walk at the highest speed. We went bullet forward covered by a cloud of hail. Looking into the fading darkness, I could see the low Albanian coast and the black mountains of Montenegro falling down into the sea.

Amery: Here are the ballistas’ debates with the Zogists over defeat

In his book “Sons of Albania” published first in London in 1947 and then in Tirana a few years ago, the former British missionary, Juljan Amery, describes in detail the contradictions that had between them the Albanian nationalist leaders, who they did not hesitate to resurrect them even in the last moments before the departure of the British. In this regard, he recalls, among other things: “Meanwhile, the news had spread that we were on the coast and what was left of the scattered nationalists, began to penetrate into our camp through German and partisan lines. The most optimistic among them recalled that we had left the mountains to prepare for the British landing, and even the leaders hoped that they could protect them from the partisans. Mit’hat Frashëri, Ali Këlcyra and the main members of Balli Kombëtar came to us on October 16th. With dignity and prudence, they conducted surveys to see if we were ready to send them to Italy. A previously lacking faith added to our obligations to them, but it was not worth asking for these nationalists what we had been denied for Abbas Kupin. Our insidious responses must have sounded in their ears like a death sentence, but they listened to us calmly. That night, Ali Këlcyra was held better than anyone. Yet in the early hours of the morning we woke up to the shivering groans coming from the chip of the room where he slept. Someone lit a match and we saw that fatziu was possessed by an anxiety. Mit’hati woke him up carefully and Ali, who was still trembling, told us that he had seen a terrible dream as if he were being tortured by Enver Hoxha with a knife. We had already realized that the threads of an alliance are untied, if victory is certain, but such a thing happens even before a defeat. The common denominator had united Republicans with monarchists, but the catastrophe of defeat was reviving disagreements. Abas Kupi accused the Ballists of discrediting the nationalist cause in the eyes of the British by joining the Germans. . Blaming each other may have seemed like something academic, but they hid in themselves a conflict of natural interests. The two parties, which could not support each other in Albania, could soon split into exile. Whereas now that the resistance had ended, the Zogists and Ballists looked like rivals trying to gain British support, rather than allies against the partisans. Agai was determined to break away from people who had “collaborated” with the Germans, while the ballistas still hoped to defend themselves behind his name. We never asked what happened between them that day, but when the meeting ended, the ballista leaders said goodbye and headed back to the mountains with a view of convicted men. After Mit’hat and Ali, Fiqiri Dineja arrived. He wanted to discuss the circumstances of the end of our resistance or our departure. At the same time, he wanted to know what expectation the British could reserve if he was thrown into Italy. With all his desertion and passing to our side, we could give only a little encouragement to a former quisling, while Agai advised him to regain in the mountains, the fame he had lost in Tirana. He left us to go to Debar again. Meanwhile, our camp remained a gathering place for nationalists of all kinds, who had instinctively pinned their hopes on Abbas Kupi. Among them came a delegation from the Catholic highlanders of the Great Highlands. They invited Again to organize their resistance against the partisans. Abaz Kupi shouted at the Catholic leaders in our presence and rejected their proposal, saying: “This is something against the will of the English and although they can forgive me, I still will not go against them.”

Kupi: What if we had Mirdita with us?!

According to the memoirs of the British Julian Amery, the former military missionary who happened to be in Albania in 1941-’44, in the last moments before leaving Mount Vela, Abaz Kupi turned his gaze from the East and said: Ah if we had had Mirdita with him? But what did Kupi mean by these words? In this regard, Amery says: “Before leaving for the coast, we climbed with Abaz Kupi on the rocky ridge of Mount Vela, to see for the last time the hills and valleys where we had fought and were exhausted. A beautiful day helped us on our journey and the effort of climbing was rewarded by the grandeur of a view that included many parts of Northern Albania. Looking from the south, I recognized the rocky ridges and plateau of Biza where seven months ago we had parachuted at night. From there, I followed the path that had led us to the Zogist towers of Mat, Kruja and Tirana, whose fertile valleys and bear mountain ranges were full of pleasant and intimate memories. The city of Tirana was hidden from the ridge of the mountains that guarded it, but through the field, beyond the minarets of Preza, I could barely see the contours of Durrës, where Abaz Kupi had raised for the first time the flag of the Albanian resistance. To the east lay the wavy forests of Mirdita, the “land of happy days” that we had crossed as illegals and that had never accepted us as friends. Beyond them, the serrated ridges of the Luma rose, on which we had exhausted Muharrem Bajraktar. While in the north the view was obstructed by the dark massif of the mountains of Gjakova, where the invincible Chiefs had conducted their lonely war. The flow of the Drini was hidden from the mouths of the Luma, but beyond Kukës where the Black Drini joins the Drini e Bardhë, I could see the river that meandered to the north to fall around the foot of the Namura Mountains and turn south, to was poured into the sea, one thousand five hundred yards, down from the top where we had stood. From the north, across the river, rose the red towers and minarets of fanatical Shkodra, and between the gray waters of its lake and the sparkling Adriatic, the skyline was interrupted by the mountain range of Montenegro. Everywhere around us lay all the value of those who had lost and while we were sitting looking down I heard Abbas Kupin say almost to himself: “If only Mirdita had been with us…!” / Memorie.al