From Bashkim Trenova

The twentieth part

MYTH-MYSTICISM, VICTIMOMANIA, RACISM AND SERBONOSTALGIA

ALBANIANS ACCORDING TO THE SERBS

(THE EASTERN CRISIS AND THE BALKAN WARS)

Memorie.al / “Serbs are descended from the Slavs, a large number of tribes who gave life to the Slavic peoples. Knowledge about the origins of the history of the Slavs is modest and not so clear. Their name appears for the first time in the 6th century AD, when Byzantine writers start talking about the Slavs….”! (Dushan Bataković, Milan St. Protic, Nikola Samardžić, Aleksandër Fotic. History of the Serbian People. L’Age d’Homme. Lausanne. 2005. Pg. 3.)

A DIFFERENT VIEW

Aleksandar Pavlović – researcher, Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory, University of Belgrade:

In this paper, it is asserted that negative representations of Albanians in Serbian culture became dominant only in the last quarter of the 19th century. In the first part, examples of positive mutual perceptions between Serbs and Albanians from oral tradition and from the works of ethnographers and early Balkan historians from the half of the XVIII century to the second half of the XIX century are used. The respect for Albanians as brave warriors and heroes, which we find in these examples, derives, as the paper asserts, from the similar social arrangement and common patriarchal values in both ethnic groups. (1)

—

In the second part of the paper, I will focus on the lack of continuity of mutual perceptions between Serbs and Albanians, highlighting the process of the weakening of the heroic discourse and the strengthening of the national discourse in the period after 1878. In this period, a series of factors, such as the international recognition of the independence of Serbia and Montenegro, the strengthening of the Albanian national movement, the weakening of the Ottoman power in the Balkans and the territorial claims around Kosovo and Metohija/Dukagjin and Northern Albania, gradually bring an increasingly pronounced increase in the appearance of Albanians in Serbian culture.

Thus, in this period, among the Serbian intellectuals, the dominant opinion towards the Albanians as northern Albanian highlanders, Catholics and allies of the Serbs against the Turks weakens, and instead the figure of the Muslim Albanian, who becomes an ally with the Turks and a torturer of the Serbs, becomes dominant few left in Kosovo. I think that this perception appears in parallel with the creation of the geopolitical concept of “Old Serbia” and the growing interest in the territory of Kosovo and Northern Albania. (1)

1 – Aleksandar Pavlović (Aleksandar Pavlović). New Europe College, Bucharest /Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory, University of Belgrade. From heroes to savages: the Albanians in Serbian heroic and national discourse from the mid XVIII to early XX century. Pg. 15.

Of course, it would be excessive to draw the conclusion based on these sources that there were no enmities or conflicts between the Serbian and Albanian populations, especially if it is taken into account that in the tribal societies of the Central Balkans, between the families, tribes or clans of certain these were a common phenomenon. However, I think that the mentioned texts show that Serbs and Albanians in this period did not see their relations mainly through the terms of hostility and mutual intolerance. (2)

—

In short, before and during the Balkan Wars, anti-Albanian tendencies grow and turn into a real media propaganda, reaching the peak with several “academic” monographs, which were openly racist towards Albanians. Thus Albanians, who for a long time have been seen as heroes, appear in Serbian culture more and more with terms such as “fury”, “savage” and “bloodthirsty”!

(Simič, 1904; Haxhi-Vasiljevic, 1906; Oraovac, 1913; Đorđevič, 1913; Protič, 1913; for a summary of these works, see: Milosavljevic, 2002). (1)

—

1 – Aleksandar Pavlović (Aleksandar Pavlović). New Europe College, Bucharest / Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory, University of Belgrade. From heroes to savages: the Albanians in Serbian heroic and national discourse from the mid XVIII to early XX century. Page 17.

2 – Right there. Pg. 24.

—

Nationalism tends to project views that, in recent times, have been formulated in relation to the ancient past. However, in our deepest past, there is simply no anti-Albanian text, not even negatively intoned. In fact, there are a considerable number of eyes that see the Albanians in a positive light.

The Great Eastern Crisis of 1875–1878 upset the balance in the Balkans. Apart from Serbia and Greece, now de facto independent, national aspirations were also expressed by Bulgarians, Albanians and Serbs from Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Great Powers wanted to establish balances of influence at the Congress of Berlin in 1878. From that time a vigorous campaign began, culminating in the declaration of war in 1912.

In these circumstances, the once dominant image of Albanians as brave highlanders, who, like the Montenegrins, live in gender and tribal communities, who value heroism and honor, often cooperating with us in the fight against the Turks, becomes unstable. In scientific discourse, in the media and in education, Albanians are now increasingly defined as allies of the Turks and torturers of the few remaining Serbs in Kosovo. (2)

1 – Aleksandar Pavlović (Aleksandar Pavlović). New Europe College, Bucharest /Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory, University of Belgrade. From heroes to savages: the Albanians in Serbian heroic and national discourse from the mid XVIII to early XX century. Pg. 28.

2 – Aleksandar Pavlovic. Interview published in the weekly “Vreme” 13.02. 2021.

—

It is constantly said in Serbia that it is not easy for us to give up Kosovo because of tradition…. The basis of the entire tradition written about Kosovo is that after the Battle of Kosovo we have received in medieval Serbian literature about twenty writings in a period of twenty years, written by monks, church dignitaries, writings of the church genre, having some ritual function. However, this tradition is not national. We have Prince Lazarus as a martyr, someone who consciously sacrifices himself for Christianity, for the faith. We have no national symbols here, not even the mention of Serbs; we have Christians and Kosovo as a religious symbol. As for the heroic folk songs and oral tradition, they mention Miloš, Lazar and Kosovo as a place of battle.

After Vuk Karadzic, we have a moment when Kosovo is already mentioned as a country, as a territory, and this comes to the focus of interest of the Serbian public. However, there is still no demand for us to return to that territory, the sentences “now we need revenge” or “Kosovo should be a Serbian country” are not heard…! But, since 1850 we can see how a great interest in Kosovo is developing in Serbia. In fact, here begins the trend that everything real, what is real in Kosovo, we see through some medieval symbols and myths. (1)

****

Ana-Maria Martac – journalist:

Finally, the independent daily Danas published on Wednesday and Thursday a long “open letter” addressed to Milosevic, penned by a former Tito foreign minister, Milosh Minic. “Since you are still the President of Yugoslavia”, writes Miniç with irony, and since “we watch, thanks to Montenegrin and foreign televisions, the images of these mass graves where Albanians have been thrown, maybe up to 10,000 […], you should answer the following questions”. And the former minister asks:

“Who gave the order for the ethnic cleansing of Kosovo Albanians, which armed, police and paramilitary forces are guilty of these war crimes, who gave ten minutes to the Albanian families to flee, who are the ones who looted their homes, set fire to, identity documents were destroyed so they could not be returned?” And to conclude: “In the eyes of the Albanians and the world, the entire Serbian people will bear responsibility for these war crimes, as long as the real supporters and real executioners are not brought to justice”. (1)

1 – Aleksandar Pavllović: Kosovo for Serbia is not a national matter; a-news 24. 26. 02. 2021.

****

Anđa Srdič Srebro – PhD holder of the third cycle in ethnology and anthropology, etc.:

First, let’s say a few words about the Myth of Kosovo and the role that epic songs have dedicated to Prince Lazar. In describing the war of the Serbs against the Ottoman invaders, the popular poet raised the Battle of Kosovo to the stage of a symbol of the war between two worlds – good and evil – emphasizing moral principles, which highlight a certain ethic. This ethic, which somewhat resembles that of chivalry in the West, is quite simple: it exalts heroism, freedom, justice and sacrifice, while criticizing lack of courage and treachery. In such a view of the world, it is undoubtedly the character of Prince Lazarus who must have fascinated the popular poet the most.

Because he was the one who showed courage fighting for the freedom of the homeland; it was he who sacrificed himself before an alternative: namely, instead of accepting slavery in order to hold as sovereign the “earthly kingdom,” he chose freedom in death, and, through this death and his sacrifice, he chose the “heavenly kingdom” and, hence, eternal life. This cult of Lazar, the cult of the “martyr” propagated above all by epic poetry, will later be connected, as we said, with that of Vid, which then paved the way for the legalization of the religious celebration of the anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo , celebration officially dedicated to “Vid Day” – Vidovdan (June 15/28).

This process, which led to an unexpected symbiosis of the two cults, is quite complex, so it seems useful to give an additional explanation here. First of all, it should be noted that previously “Vid’s day” in the Orthodox calendar was almost certainly dedicated to Saint Amos and that the term Vidovdan came into use only in the 19th century. But where does the name St. Vid come from, a character completely unknown in the Orthodox tradition? Some scholars believe that St. Vid is simply a distant Christianized memory of a pagan deity (the god Vid, or Svetovid) and can serve as a good example of the incorporation of folk beliefs into Church practices. (1)

—

This process, which led to an unexpected symbiosis of the two cults, is quite complex, so it seems useful to give an additional explanation here. First of all, it should be noted that previously “Vid’s day” in the Orthodox calendar was almost certainly dedicated to Saint Amos and that the term Vidovdan came into use only in the 19th century. But where does the name St. Vid come from, a character completely unknown in the Orthodox tradition? Some scholars believe that St. Vid is simply a distant Christianized memory of a pagan deity (the god Vid, or Svetovid) and can serve as a good example of the incorporation of folk beliefs into Church practices. (1)

1 – Ana-Maria Martac, Kraljevo, Cacak and Belgrade. Le Temps. 2. 07. 1999.

—

To end this story of the prince’s relics, but also to show that his cult is still very much alive, let’s add one last detail. Believing that the time had come to return the “holy body” of Saint Lazar to its home, the council of the Serbian Orthodox Church decided to bring the relics to Ravanica. But this decision was implemented only during the celebration of the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo, in 1989. On this occasion, we wanted to recall the strength of the symbolism of the cult of the “martyr prince”, especially since Kosovo, which is valued by the Church as the “Serbian Jerusalem “, has once again become “the place where Serbian historical fate was played”.

Thus, from 1988 to August 1989, the relics of Saint Lazarus were exhibited during this ritual journey along the streets of many Serbian cities and monasteries. Finally, a tribute to the Holy Prince was celebrated in the presence of one million Serbs in Gazimestan, the site of the Battle of Kosovo, before his relics were placed in the monastery of Ravanica in Kosovo, where they are still kept.(2)

1 – Anđa Srdić Srebro. Corporation des croyances populaires dans les pratiques de l’Église. (Inclusion of popular beliefs in church practices). Serbian Studies Research. Vol. 5, No. 1 (2014). Pg. 73-74.

2 – Right there. Pg. 74-75.

We have focused our analysis on these three cults of saints because, in our opinion, they are the most representative of the Serbian religious tradition. Of course, we could have studied other examples of canonization belonging to the same tradition, especially those of saints belonging to the royal “holy line” of the Nemanic dynasty. The case of Stefan Decanski, for example, also seemed interesting to us to analyze: his cult has over the centuries occupied an important place in the religious life of the Serbs of Kosovo and Metohija, his grave has attracted generations of pilgrims, while his relics have served as objects of veneration by those who suffered – the blind, the sick, childless women, etc. But it seems to us that the three analyzed examples are sufficient to illustrate the beliefs and religious practices of the Serbs related to the cults of saints. (1)

****

Biljana Milanovic – near the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts:

While at the beginning of the 20th century the Macedonian issue had reached its climax with the armed intervention against the rivals, another conflict developed in parallel between the Albanian liberation movements on the one hand and Greece, Serbia and Montenegro on the other. At the beginning of the 20th century Dimitrije Tucovic had denounced local Balkan imperialism. But the democratic and social solution of the national issue through the right of popular self-government was characterized by its imprecise and unfinished character.

Mokranjac wrote his last “bouquet” in 1909. This is the time of the Serbian orientation towards the southern regions and of the many stages in the creation of the Balkan Coalition. Thus, the peak of the process reaches during the Balkan wars (1912-1913) with the strong imperialist acts in the fight for access to the sea and the occupation of Durrës. This period is surrounded by a background of complex, intertwining phenomena: unifying, liberating and expansionist tendencies of official Serbian ideology.

The concept of the Serbian nation, which culminated in the Balkan Wars, was initially based on the application of different criteria of language and religion. The first defended the unity of the nation in the Stokavian dialect with the phrase: All Serbs together, and the second orthodoxy, with the proverb – Serbia is where the Slava is, the aim to connect language and religion, was complementary to the preaching of a common ancestral past. This past is built on the features of two Serbian founding myths: the myth of Saint Sava (religious) and the myth of Kosovo (folkloric). (1)

1 – Anđa Srdić Srebro. Corporation des creyances populaires dans les pratiques de l’Eglise. Serbian Studies Research. Vol. 5, No. 1 (2014). Pg. 75.

****

Bogdan Bogdanovic – architect of Yugoslav memory, original thinker, taught “urbanology” at the University of Belgrade:

Serbs should not forget that when Kosovo was the cradle of the Serbian kingdom, Belgrade was Hungarian! Since then the Serbs have moved to the north: there is nothing tragic here, the only problem remains these Byzantine churches, really beautiful and interesting, but this problem could be solved with an international agreement – which the Serbs never wanted to accept. This, in the name of orthodoxy, which now demands that Serbs politically dominate a country they have abandoned! In addition, there is a whole mythology about this, as an architect I have traveled around Kosovo. I have seen many of these monasteries: they are beautiful, of course, but nothing more. (2)

1 – Biljana Milanovic. Stevan Stojanovic Mokranjac et les aspects de l’ethnicité et du nationalisme. (Stevan Stojanovic Mokranjac and aspects of ethnicity and nationalism). Études Balkaniques 13|2006. Pg. 145-168.

2-Bogdan Bogdanovic. Rencontre européenne n°7 – February 2008.

****

Cedomir Jovanovic – politician, chairman of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the parliamentary group of the LDP in the National Assembly of Serbia:

Why do we deal with lies? Unfortunately, Kosovo is an unfortunate reality for Serbia, a sad, tragic reality, but this is the truth. Can we believe that, relying on illusions, oaths and the appeals of myths, we will achieve the result desired by Serbia and which belongs to it? Today we are not accusing anyone, but we are asking to be ready to bravely face the future and send the message to Serbia that in this era it must be freed from prejudices and mistakes, which have cost it so much, we are aware of the great truth: there is no happiness in Kosovo without the reconciliation of the Serbian and Albanian people. (1)

****

Damjan Pavlica – political scientist, journalist:

At the beginning of the 20th century, the province of Kosovo was a province of the Ottoman Empire, whose territory was significantly larger than the territory of today’s Kosovo. It included all of Kosovo, Sanjak, the Presheva Valley and western Macedonia. The seat of the vilayet of Kosovo was in Skopje. The majority of the population of Kosovo was Albanian. At the beginning of the 20th century, Kosovo was the center of the Albanian national revival and the struggle for liberation from the Turks. From 1905 to 1912, the Albanians launched an uprising to gain cultural, economic and political autonomy. The Turks regularly put down the armed rebellions of the Kosovo Albanians in blood.

1 – Cedomir Jovanovic. Osveta Kosovo. (Kosovo’s revenge). Radio Pescanik. 22.02.2008.

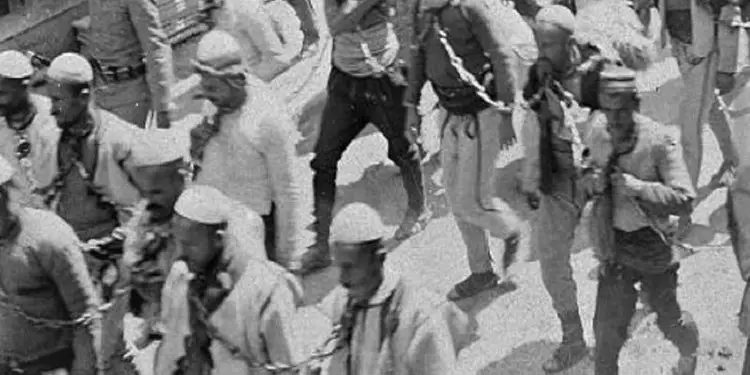

In October 1912, Serbian and Montenegrin armies attacked the Ottoman state, entering Kosovo and Metohija. The Albanians opposed the occupation of their settlements and organized volunteer units, which made an armed resistance to the advance of the Serbian troops.

During the Balkan wars of 1912-1913, Serbia annexed the areas of Sanjak, Macedonia, Kosovo and partly Albania…. “Entire houses and villages have been reduced to ashes, the unarmed and innocent population has been massacred en masse, extraordinary acts of violence, plunder and cruelty of all kinds – these are the means used and still used by the Serbo-Montenegro army, in order to completely change the ethnic character of the area inhabited exclusively by Albanians.” (From the Report of the International Commission on the Balkan Wars.)

There was a lot of talk in those years about the “revenge of Kosovo” for the year 1389, which flowed as if by magic from the Turks to the Albanians. Such a policy did not pass without criticism in the European press, which wrote about the crimes of ethnic cleansing committed by Serbian and Montenegrin troops during the occupation of Albanian settlements. After the end of the First World War, Kosovo belonged to the newly created Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Kosovo became a Serbian colony, and a mainly military administration was established there. Serbian politicians did not have any plan for Kosovo, which would take into account the interests of the Albanian population. There was simply a prevailing opinion, according to which the Albanians should move and the Serbs should settle there.

Between the two world wars, the Belgrade government pursued an extensive colonization program, with the aim of changing the ethnic structure of Kosovo in favor of the Serbs. Former soldiers and members of Chetnik units had priority in placement. By 1941, some 60,000 settlers lived in Kosovo, often on properties confiscated from Albanians. Over 90% of the total number of colonists was Serbs from various parts of Yugoslavia (which at that time also included Montenegrins). The confiscation of the houses of the Albanian peasants, in order to settle the colonists in them, caused hatred towards the colonists and left lasting consequences in the relations between the Serbs and the Albanians.

In 1935, the Yugoslav authorities held a meeting of several ministries and the General Staff, in which a project was drawn up “on the emigration of the non-Slavic element from Southern Serbia” to Turkey. At the beginning of 1936, Turkey expressed its readiness to conclude an agreement with Yugoslavia for the emigration of 200,000 inhabitants “who are related to the Turkish mentality and will easily assimilate in Turkey”.

In 1937, the Serbian academic Vaso Čubrilović drafted a project for Stojadinović’s government to quickly solve the “Albanian problem” with mass ethnic cleansing of Kosovo: “it is impossible to suppress the Arnauts only by gradual colonization. The only way and the only means is force brutality of a government of an organized state”.

Professor Vaso Čubrilović detailed the methods of ethnic cleansing, which include the creation of mass psychosis, the distribution of weapons to the colonists, the sending of armed Chetniks, state repression, arrests, persecution, removal of work permits, expulsion from the service, deforestation, the violation of cemeteries, setting fire to settlements and other similar ones.

From July 9 to 11, 1938, a working meeting of Yugoslavia and Turkey was held in Istanbul for the preparation of an agreement on the emigration of Albanians. The parties reached an agreement on the relocation within six years of 40,000 Albanian families from Kosovo, Macedonia and Montenegro to the desert areas of Anatolia. Under the agreement families could have over 100 members, so 40,000 families could amount to several million people. Article 2 of the agreement provided for the complete relocation of Albanians from many cities, including: Prizren, Ferizaj, Pristina, Kaçanik, Gjilan, Presheva, Peja, Istok, Mitrovica, Gjakova, Vushtrina, Drenica, etc.

In 1985, members of the “Serbian Resistance Movement” from Kosovo, assisted by Atanasije Jevtic and Dobrica Qosic, sent a petition to the state authorities. It said that the province was ruled by “the biggest Albanian chauvinists”, who “occupied a part of Yugoslavia” and committed genocide against the Serbs. In 1986, the influential Memorandum of SANU (Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts – author’s note) was published, which called the demonstrations of Albanian students “neo-fascist aggression” and where it was emphasized that Kosovo was being “physical, political, legal and cultural genocide against the Serbian population”. However, none but the Serbian authors described the problems as genocide. SANU’s memorandum was later assessed by the United Nations commission of experts as “a tool for spreading anti-Albanian sentiments”.

According to a Human Rights Watch report, the Serbian media in the 1980s deliberately spread false reports about atrocities against Serbs in Kosovo, including the rape of Serb women, and ran a hate campaign spreading negative thoughts about Albanians.

In early 1989, Slobodan Milosevic forcibly removed Kosovo’s autonomy. Milosevic’s triumph was immortalized on June 28, 1989 in Gazimestan, during the celebration of the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo. In his speech, Milosevic called Kosovo the heart of Serbia, which later became a widely accepted political slogan. He further declared, in front of about 300,000 people, that “even armed battles are not excluded”. This statement is regularly seen today as an announcement of the Yugoslav wars: “We are again before the battles and in the battles”.

Milosevic’s speech marked the end of the Yugoslav idea and he moved from the role of the communist leader of Serbia to that of the national leader of the Serbs. On the occasion of Milosevic’s triumph in Gazimestan, Rugova (1989) uttered the almost prophetic words: “Gazimestan is a chauvinist manifestation. It was not only the Serbs who fought against the Turks. Albanians, Croats and Bosniaks also participated in this battle, which is an important event for all Yugoslav peoples. My impression is that there are forces in Yugoslavia that almost want terrorist actions in Kosovo. I can only warn the Serbs that whenever a small nation, and the Serbs are a small nation, has tried to impose its supremacy in the Balkans, it has ended in its own personal tragedy.”

As we have seen, the problem of Kosovo did not appear today or yesterday, it has existed since Kosovo entered our country. Many Serbs, with whom I have spoken, would like the Kosovo problem to be resolved so that all Albanians disappear from there. I think this is not realistic, and above all it is not humane. Memorie.al