From Shkëlqim Abazi

Part Fifty

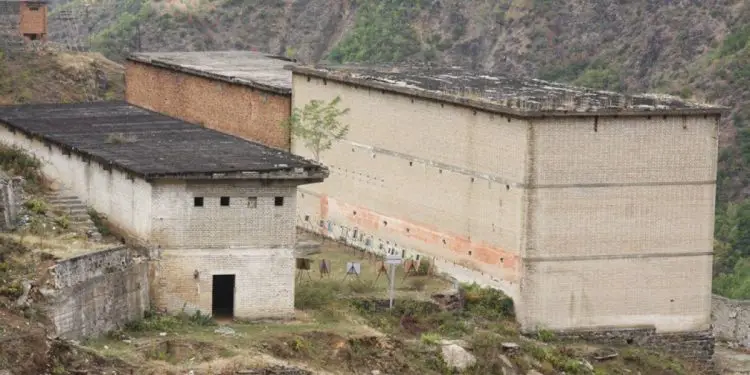

S P A Ç I

The Grave of the Living

Tirana, 2018

(My Memoirs and those of others)

Memorie.al / Now in old age, I feel obliged to confess my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds, and of others whom the regime silenced and buried in the nameless pits? In no case do I take upon myself to usurp the monopoly of truth or to claim laurels for an event where I was accidentally present, although I wholeheartedly tried to help my friends even slightly, who tactfully and kindly avoided me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you only have two months and a little left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet, from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months that followed, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard those three days, I would not want to take to the grave.

Continued from the previous issue

“He’s alive!”

“Alive! Alive!” – repeated the others.

“Oh God, the unprecedented happened; we are wresting corpses from the hands of ‘Polyphemus’!”

“Hurry, men, to the infirmary!” Hope was reborn.

Four men placed me on a tarpaulin fixed onto two shovel handles and rushed down the hill, followed by dozens who took turns along the way. On the steep slope of the “Calvary,” along the road where the mineral-transporting trucks were driving, the soldier had screamed from the watchtower:

“Turn back! Stop or I’ll shoot!”

But I, or the alter-ego watching over the tarpaulin coffin, answered him simultaneously: “Shoot and kill the dead man!”

My comrades paid no heed to the threats of the soldier, or to my alter-ego, but challenged the state that kept silent, or hindered with confused orders, when it had the duty to protect lives.

“He died, hey man!” – Corporal Preng Rrapi had expressed when the body was hidden under the mountain. – “Leave the dead man where he is and meet the norm!” – he referred to the commander’s order.

But my stubborn friends did not give up:

“We won’t leave him as a hostage to Polyphemus!”

“Continue, men, maybe God… fate wants him alive!” – encouraged the one they didn’t expect; “Mark the Giant,” the corporal of Unit 303, Spaç, Mirditë!

So, even among them, there were people with soul, albeit rarely. The differentiation within the species prompted the comrades, who disregarded the fact whether I was dead or alive, because they still hoped. The more miserable life is, the more it hurts! As misery awakens dormant consciences, misfortune orients scattered minds, cultivating the spirit of cooperation against state violence.

Although the state insisted on abandoning the search, my fellow sufferers increased their self-denial, because they were striving for life. Amidst gasping, pain, and sweat that flowed in streams, they did not stop their efforts. The mystery of tomorrow forges the solidarity of today! Pure souls are encountered everywhere, one such was even found among the police, even though they equated us with worn-out hides.

“Continue, men, maybe God… fate wants him alive!” “Mark the Giant” had repeated. My friends believed in life and hope did not disappoint them!

They at least tried to fulfill the last wish of every mortal, to lay him on the straw mattress, so they could send off the corpse with dignity. Because every dead body deserves the service, thus they leave it to stiffen on the bed where it breathed its last, before taking it to the morgue. To feel at peace before their conscience and God, they rushed to the door to lay me on the mattress before the police would accompany me “upstairs” to continue the “toilette”; meaning to break the bottom of my spine, stuff me into a micro-coffin, and bury me near the other unfortunate ones.

I would have been forgotten in time! I would have settled accounts with this world of gall, but… God had prophesied the future differently! A return from the afterlife. But… I don’t know who had reported my death.

Perhaps the news had traveled from the workers to the six-hundreds; perhaps the owls from the tops of the tar-paper roofs announced it, screeching whenever misfortunes happened; perhaps the gales that fiercely struck this pocket forgotten by the world had carried it to the Spaç valley; perhaps the tense police had been babbling from overtime service?!

Regardless of the source behind the communicating door between the two camps; old friends were waiting. The six-hundreds were waiting, sucking on their pipes in the corner of the dormitory; Malo the crier was also waiting, who did not scream shrilly, fearing he would disturb the missing comfort of the dead man; the spy cat stayed silent, crouched behind the four-by-four, with eyes squinted and ears perked, as if ambushing a mouse; in fact, that morning, as rarely before, even “Marroku” had abandoned the chessboard, leaving the imaginary “opponents” facing each other, and he hadn’t even babbled nonsense, even though he didn’t care at all about the trivialities of this false world!

Van Xhuvani was waiting with his first-aid kit, he who stitched up the skin stripped from me by Preng Rrapi’s whip the day I stepped into the cursed camp. Meanwhile, the flock of Zefs was waiting and praying according to their inclinations, the priest addressed God, the officer cursed the regime, the worker cursed the misery, and the peasant cursed the land, while the poet begged Orpheus. Perhaps the phantom of the Shkodër cells, who had prophesied: “Hold on, boy Çim, you’ll leave seven skins in prisons, if you manage to make it, if you have that luck!” was also waiting with them.

If I didn’t catch the count this time, I would never make it! Perhaps even… Saint Peter was waiting, with his biblical beard and scepter in hand, to guide me to the gardens of Eden, or to the abysses of Hell. The police pack was also waiting, cawing:

“Far from here, you!”

“Get away from there because that’s the ideal of the Party…”!

“You convict, the soldier will shoot you, that’s a forbidden zone there!”

But even the soldier echoed them from above the watchtower:

“Stop! Turn back or I will shoot!”

Yet, since no one paid attention, he did not shoot, because the dead man cannot be killed again! But even the “road of suffering” had its starting point on the barren ground, within the “no-go zone,” where the “Calvary” began, trodden by wretches worn out like corpses, dressed in rags that a dog wouldn’t even touch.

But everyone adapted to the scenario presented to them by the Great One in Tirana and performed their ritual: the police screamed, the soldiers threatened, the dogs gnashed their teeth, while the prisoners remained silent. The endless calls exhausted everyone, especially the police who didn’t want to prolong it further, so they insisted on taking me up:

“In the end, the dead man belongs with the dead, you!” – One of them had said.

“We can’t waste time with corpses, comrade, our wives and children are waiting for us at home!” – another had cut in.

To shorten the procedure, they justified their actions and insisted on taking me to the morgue, but the comrades stood firm on taking me to the dormitory, or at least the infirmary, where the doctor could confirm the death.

“Come on, convict, Kosovrasti will perform the autopsy there!” – Preng Rrapi had attempted one more time.

The doctor completed this routine in the command offices, or in the improvised morgue, also near the offices, but often they wouldn’t let him approach the mangled corpse at all, as if it had been torn apart by dogs. He would merely fill out the death certificate and list the causes that were served to him. Finally, he signed before passing it on to the military doctor.

It happened that for the most trivial reasons, the act was concluded after the unfortunate man had been buried in some ditch; consequently, the military officer didn’t even examine the corpse, so when it came time to close the formal process, the act had turned into sarcasm:

“Sign it, it’s not the end of the world, one less enemy,” his superiors advised him, and the doctor scribbled his signature arbitrarily, without a prick of conscience for human fates.

“Time’s up, you!” – a police officer complained at the entry-exit gate.

“What time is it, Ndrec!” – the other asked him.

“It’s past twelve o’clock now!”

“It’s late, by God!” – sighed the one who had complained.

“Up, or dinner will catch us!” – ordered the zealous Preng Rrapi.

“Sir, we need life, not the hour!” – Esat Kala had intervened.

“You have the shackles, we have the hour!” – And Prenga had tapped the glass of a cheap watch, tied with a paper strap, with his index finger.

“Enjoy it, your hour has passed…, we have time in our favor!” – Esati retorted.

“To the irons and the cell, you!”

Amidst these debates, Vani had cried out:

“Alive! Quick, to the doctor!”

“Upstairs, dammit!” – Corporal Prenga had insisted, angered.

“He is alive, sir!”

“I give the orders here, you!” – the arrogant police officer interrupted him.

“Life is not given by orders, Mr. Police officer! I told you he is alive!”

“You made us laugh, this one finished his time, you!” – and Prenga had burst into satanic laughter.

“For me, he is still alive, period!” – the offended Vani had insisted.

“Hurrah-a-a, alive, life-e!” – “Marroku” had burst into cheers.

“Meow-u!” – the cat had replied from the roof.

“Alive, a-a-a!” – Malo the crier had screamed, like Columbus’s exhausted sailors when they spotted the eastern shore and shouted: “land-d-d.”

Perhaps this automatic crier was truly shedding tears for the first time in his career?!

“Alive-e-e, land-d-d!” the gorge of Spaç had roared, and the echo had scattered across the slope, penetrated the caverns of the galleries, reaching the ears of “Polyphemus.”

“Oh-oh-h!” the monster had groaned, shaking the mountain, spinning thousands of tons of rock, sand, and acid over the abyss, now without human harm. This seismic shock jolted the group, who grabbed the stretcher and rushed to the infirmary. “To the doctor,” – Vani had ordered and led the way. The nurse of the hellish prison turned into a messenger of life!

Weakness broke the police harshness; life triumphed, challenged the prison, and shook the state!

In the “Kingdom” of Muhamet Kosovrasti

From the claws of “Polyphemus” to the most isolated infirmary on the globe, which Muhamet Kosovrasti called: “my clinic”! In his “kingdom,” there were no orders, no command, no police, only the doctor, who had declared death non grata, fought it, and felt happy when he triumphed; when he sometimes lost, he sank into despair, retreated with books, refreshed his thoughts, regenerated his strength, ignored the loss, and prepared for future battles.

He drafted plans by consulting himself, gave orders and executed them himself, and answered the hypotheses he posed himself. In “his clinic,” whiteness reigned; a white face, white hands, a white blouse. While many saw the doctor’s figure as black, inside those walls, whiteness fluttered.

The doctor, with a controversial personality and a very deformed and suspicious character, was as servile, suffering, and submissive with the authorities, as he was unapproachable, cynical, and arrogant with almost most of his fellow sufferers. You could pass him twenty times a day, and he wouldn’t deign to return a good morning or good evening; his hand trembled for one day of medical leave, even when you deserved it.

The divided type, with a crude appearance, changed as soon as he crossed the threshold of “his clinic” and donned the white blouse. The black-souled cynic was transformed, as if in an optical vision, into a disciple of Hippocrates, a misanthropic anthropophile and miracle worker; the flaws of the individual with vices remained outside the door.

Perhaps the environment resurrected the doctor! There he felt like a king, a prince, a singer, a poet, in a word, a healer of organs and the body. I cannot explain that metamorphosis; as soon as the reflections of the medical instruments sparkled and he smelled the aroma of medicines, Muhameti became Kosovrasti, a talented healer, and incomparable to many in his profession.

You could not discern these qualities without being a patient in the sterile environment, because that difficult character was surrounded by a multitude of ominous rumors. Thanks to his care and professional abilities, I was one of the patients who survived, without serious consequences. Willingly or unwillingly, during my immobility, I exchanged some opinions regarding health, but when these dried up (and he deliberately exhausted them by provoking topics outside the sphere), you became convinced that he possessed knowledge even beyond the medical field.

When you communicated with him, you noticed that his intellectual interests extended beyond his profession, and he possessed a satisfactory level of knowledge about the latest news. He discussed art, literature, and culture at superior levels, but as soon as he touched on political topics, he immediately hesitated and took on a lemon-like complexion; his eyes darted like a squirrel’s, as if he had installed telepathic sensors in them.

Terror was readable in his eyes. Was he afraid of lynching, or did the unsettled score with his own personality weigh on his conscience? Perhaps he was afraid of the unknown and sensed emptiness, even beyond it, the void? He opened the topics himself and immediately froze; neither I nor the nurse ever exceeded the professional boundaries. So, I didn’t believe I was the cause, Vani certainly not, so why was he afraid?! Only God could unravel that mystery!

He had been in prison for several years and knew the makeup. He also knew the circle of friends I frequented, the individuals I associated with, their professions, education, fondness for culture, letters, arts, but also their puritanical views on social formations, on family upbringing, on art, on religion, on politics; he knew that they didn’t tolerate ambiguous behavior, he knew their anti-communist convictions and their incompatibility with the Marxist-Leninist atheist dogmas propagated by the leftists; at the same time, he knew that the overwhelming majority didn’t stomach him and disliked that dualistic type, just as he knew that no one prevented me from maintaining correct relations with him and others.

A voice in my mind told me that through me, he aimed to re-establish bridges of contact with my friends. Nevertheless, I didn’t dwell on these conjectures, because I considered myself a transient patient, seeing in him the doctor who was serving me to recover. After this, our paths would separate, and we would meet as strangers. Therefore, I considered a certain understanding and mutual trust between doctor and patient as normal, which, besides health progress, failed to turn into friendship, as few achieved it.

Two weeks in the infirmary and two that followed the treatment, I noticed that I surpassed the ordinary patient. When I gained some ground, I minutely studied the repressed character within the walls of “his clinic” and provoked some topic outside his field. At that time, I got to know the individual with interests beyond medicine, with balanced ideas and a discreet anti-communism, which hid in a fragile soul. I drew the conclusion that: “This type of coward is hopeless and terrorized to the bone!”

Even a perceptive psychologist like Esat Kala paraphrased it this way: “Perhaps fundamentally he is not negative, but the mental-based phobia has instilled the fox syndrome in him!” Even two weeks after I left “his clinic,” I had difficulty walking, and I went for treatment with the help of friends. One of these days, Tomor Allajbeu, who had just finished his latest punishment, accompanied me.

I emphasized that Tomori was one of the unique ones who didn’t tolerate the doctor at all. If others merely despised him, he hated him. But when they told him about the accident that happened to me and the doctor’s sacrifice, he seemed to shift slightly from his “hostile” position and had sworn to his fellow sufferers that he would thank him in “his clinic,” as soon as they let him out of the cell.

And so he did. But I cannot describe the doctor’s surprise when he extended his hand to his most intransigent “opponent”; his mouth was sealed, and his hand remained hanging in the air. Especially when he heard a stream of thanks from the lips of the one he never hoped would speak to him, he was deeply touched, so much so that two drops of tears hung from his eyelashes, rolled down his cheekbones, and settled on his lips.

He silently licked them, finished with me, and turned to Tomori:

“You don’t look well!”

You didn’t need to be a doctor to state this, because Tomori had been punished and re-punished for a long time.

“After so many months in the cell, it’s completely normal!” – my friend replied indifferently.

“Man, since you’re here, why don’t you undress so I can examine you?” – the doctor practically pleaded.

Surprisingly, Tomori undressed and lay on the bed, where he began to fill and empty his lungs, cough, and hold his breath as instructed by the doctor. After about a quarter of an hour, Kosovrasti removed the stethoscope and began writing something on the surface of the bedside table.

“Well, doctor?” – I couldn’t wait.

“You are in an alarming state, Tomor! In my opinion, you must be urgently admitted to the infirmary, and then we’ll see the possibility for more specialized treatment…”!

He would have continued, but Tomori interrupted him:

“And then what?”

“Maybe we can send you to the prison sanatorium!”

“Are you serious?” – the surprised Tomori asked.

“Without a doubt!”

“If they let you!”

“I am the boss here!” – the doctor boasted.

“Who asks you, you poor thing?” – my friend shared his sorrow.

“As a doctor, I can do something!” – he defended his authority and continued writing.

“What are you writing there?” – Tomori inquired.

“A course of antibiotics!”

“You’re wasting your time, dear doctor, in two days I’ll be back in the rent-free hotel!”

“Why are you so sure?”

“Because they have sworn not to let me out alive, or to neutralize me physically!” He flew out without waiting for the doctor’s reaction, turned back at the threshold:

“When you finish, I’ll wait for you at the private kitchen!” – and descended.

The doctor froze with the stylus in his hand and his eyes fixed on the door, when he regained consciousness, he looked at Vani, then at me:

“What kind of man is this, he’s been in and out of the cell for a year!” – he spoke, addressing no one in particular.

“It got him, he’ll quit!” – I replied, because that tone demanded an answer.

“As far as I know, he’s from your area, and you are very close friends…?”

He searched something in the drawer, but closed it without taking anything and burst out to me:

“Talk to him, the way it has affected him, he will end up with his lungs torn to pieces by tuberculosis, or he’ll lose his mind!”

“We have talked to him, but he has no other choice!”

“Let him work, man!”

“Work is out of the question, they demand certain additions that are not in his character!” – I defended him.

“Prison cannot be endured in the cell, my friend!” – the doctor sighed.

“It truly cannot be endured!” – I supported him. – “But when they don’t leave you a way out?”

“I don’t know what to tell you, in this area, my abilities run out!” While Vani was unwrapping the last bandages, he erupted:

“So be it! I can’t stand the cells, I can’t bear the gallery, I can’t stomach physical labor, the smoggy and humid air, and I’m allergic to acid, pyrite, and dirt!”

The moment arrived when his phobias surfaced. Vani had caught the bloody, tight bandages with tweezers, to toss them into the bin next to the door.

“But you endure these!” – I provoked him.

“They are part of the profession!” – he replied indifferently and continued to apply sterilized gauze to the wound. In the next meeting, my father brought me a jar of honey, I took it to him as a sign of gratitude, he accepted it without fuss, justifying himself:

“I have invested all my mental and physical energies in this profession. You are the most typical example to prove it! And I am entitled to exploit it, am I not?” – he pointed to my wounds and added:

“We want to survive the prison, my friend, so I accept some compromise, make some concession, and even take a small bribe!”

I seized the moment and asked him about his inferiority towards the authorities, as well as the indifference that fueled the antipathy and hatred of his fellow sufferers.

“You are right, perhaps the others are not wrong either, but put yourselves in my shoes and look at the phenomena from my perspective! What do you think, why can’t I behave like others? I can, I swear! But…”!

He paused, perhaps unable to find the appropriate words or wanting to evade responsibility: “Do you think how much I would lose with stubbornness?” – he posed the question and answered it: “No, certainly not!” Memorie.al

Continues in the next issue

![“They have given her [the permission], but if possible, they should revoke it, as I believe it shouldn’t have been granted. I don’t know what she’s up to now…” / Enver Hoxha’s letter uncovered regarding a martyr’s mother seeking to visit Turkey.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Dok-1-350x250.jpg)