From Sofika Prifti Cara

Part fourteen

To Forgive…!

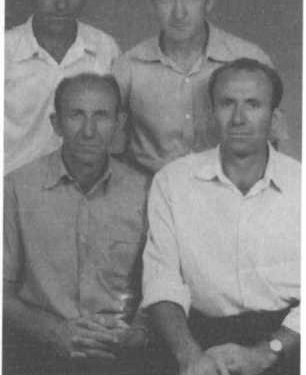

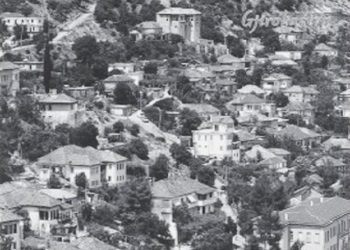

– The Old Kavajë Clan – CARA

Memorie.al/ publishes several parts from the book ‘To Forgive’, authored by Mrs. Sofika Prifti (Cara), published by the Institute for the Study of Crimes and Consequences of Communism in Tirana, in which the author has described in detail and with professional competence, the history of one of the most renowned clans, not only in the city of Kavajë but also beyond – the Cara clan, from which emerged not only distinguished patriots who contributed to the national cause and the freedom of Albania, but also famous intellectuals, graduated in the West, who later returned to the homeland, contributing to various fields of science and life. However, even though the descendants of the Cara clan dedicated their lives to the national cause, after the communists came to power at the end of 1944, they would be persecuted, imprisoned, and interned, and the fierce class struggle would follow them until 1990, when the collapse of the communist regime began.

Continued from the previous issue

Students

I return to the years 1990–’91. After Kavajë, in Tirana, students rose up and started the student movement for a new life, for a new political system, for a better, beautiful future, for freedom and democracy, for the freedom of speech, which had been barbarically denied for 50 years.

The day the youth uprooted and cast down the bust of the dictator Enver Hoxha from the square, not far from the bust of our national hero, Skanderbeg, with that manly gaze, it was as if he wanted to say to the dictator:

“For my homeland, Albania, and my Albanian people, I rejected all the offices the Sultan offered me, while you were insatiable with everything, even with the blood of the people and your comrades! You wanted to become a master above all masters, but there is only one God in the whole world! What you sought, that you found!”

On that unforgettable day, Bardhi and Xhevdeti were having dinner at their aunt’s house in Tirana. They were present at the uprooting, like a rotten molar, of the tyrant Enver’s monument by the students and the freedom-loving people. There were dozens of citizens from Kavajë, and from Bardhi’s clan too! People could not get enough of dragging him, like a dead dog.

When they came home, they were watching the news. Xhevdeti saw himself on television and exclaimed, surprised: “Oh! Look, look where I am! The camera caught me too!” Unfortunately, he had taken some rubber baton hits; the spot was swollen and bruised. But he felt no pain. He felt pride and joy and couldn’t find the words to express these feelings.

“Now, even if I die,” he told me with tears in his eyes, “I have no regrets, because we were burned and scorched because of that heartless man. My only regret is that I didn’t go and place a bunch of flowers on my father’s grave in Australia and tell him:

‘Father, you spoke for Albania, you said there was no freedom of speech here, you spoke of human rights, of the country being closed off from the world, and consequently, our lives became pitch dark at that time, turned into a thorny hell by the poisonous thorns of that system. Now sleep peacefully, because that man who made you flees and left us like pieces of meat, we dragged him out of the grave!'”

The Death of Ija

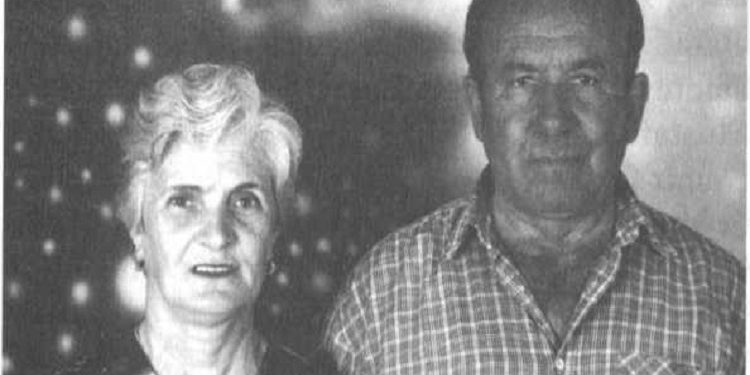

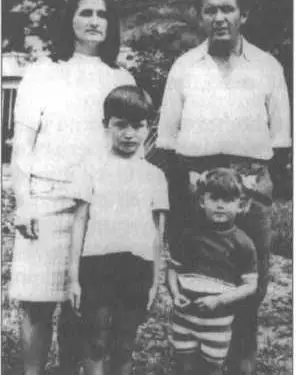

That unfortunate woman, who was Bardhi’s mother, was called Naile, but we all called her Ije (Mother/Aunt), as people from Kavajë call mothers. Ija had bad luck; she only enjoyed 11 years of marriage, as her husband fled abroad, to Italy and later to Australia.

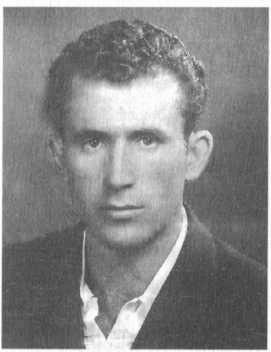

It was 1944 when he left and left four young boys. In 1939, he had left his city, Kavajë, and gone to the city of Fier. Her husband, Musa Cara, was a merchant. However, joining the “National Front” (Balli Kombëtar) led to his flight abroad. If he had stayed here, certain death awaited him. These were the first post-war days. The country was ruined by the war; misery was rampant everywhere. Poverty and destitution had entered every home.

Musa Cara had been an exponent of the “National Front,” and Enver’s government considered these people enemies of the people, condemning them, whether present or in absentia. They acted the same way with us. All of Musa Cara’s assets were confiscated: the shops, the cars, the goods, the land for a house, the warehouses, the two-story house was turned into a nursery, the land was divided for building lots, so his children were left with nothing!

Ija was very young at that time, and together with her father-in-law, Xha Lamin (Uncle Lam), they faced many difficulties in life. Nailja had brought a large dowry, which helped them during those dark and difficult days. Because giving a dowry to the marrying daughter was a tradition in Kavajë; whether they had much or little, they gave the girls a dowry, some more and some less.

Times were tough. The children demanded bread to fill their bellies because they were small. Ija, with tears in her eyes, forced by destitution, began to sell the beautiful items of that dowry, for which she had ruined her eyes, embroidering them with her own hands.

When she rose the children, and they were old enough to work, Ija married them off and thought that her troubles were over. But precisely then, the greatest and bitterest troubles began: the arrest and imprisonment of her sons, the internment of the family, intermittent provocations, and finally, the physical elimination of the two eldest sons by the people of the Enverist communist regime, which pressed her, gathered her up, and made her into a fist.

She endured like a mold, but not in spirit. She lost her patience because she knew you couldn’t hit a rock with your head, even though her sons were innocent. A popular proverb says: “The camel endured for 40 years, but finally burst!”

The day came when Mother Nailja, or Ija, fell ill with depression. We admitted her to the hospital. From high blood pressure, at the age of 61, right there in the hospital, her eye burst, precisely in the hands of the doctors, who did not show the proper care. Afterward, Ija progressed to sclerosis. She didn’t know what she was doing.

But she received very great care from her granddaughter, Irma, who truly looked after her grandmother. After much suffering and discomfort, she passed away on January 8, 1993. She died a martyr. Ija, besides her illnesses and suffering, did not see a single joyful day. Her life was dark, as the people say: “The sheep that is born black, even when it is slaughtered or dies, it is still black.” That’s how Ija died, the poor woman, without seeing a single bright day.

Her sons could do nothing for their mother, who raised them with great effort and enormous sacrifice. Not that they didn’t want to, but they had no opportunity to repay her. Ija was escorted to her final resting place with great respect. As a reward for her life full of suffering, she received only a grave, which her nephew Arian Cara made for her. Mother Nailja will remain unforgettable for life!

The Second Exodus

After the embassy doors burst open in Tirana, many Albanians, regardless of age, stayed confined within the embassy walls, waiting to leave for a new and better life. They took the path of foreign lands, putting their lives at risk. After the first exodus passed in March 1991, later the word spread about a second exodus.

In fact, we also wanted to leave during the first exodus, but Ija’s illness made us stay close to her for years, because her sacrifices to raise her four children required our support as well.

One day we found out that the ports would open, so we went to Durrës. It was the second time we went as a family. This time Durrës was surrounded by sampistët and masked Special Forces. People had come to Durrës from many cities and villages and were impatiently waiting for the port to open. They waited like sinners in the public gardens near the port.

The sampistët perhaps received an order, because then they rushed like beasts towards the crowd, which scattered in fear, some here and some there, in different directions.

I will never forget a young man from Librazhd, who was sitting on the sidewalk beside the public garden and was eating bread. We were also in that public garden. The sampistët came from the other street and suddenly appeared in front of us! We couldn’t move, and neither did he run away.

They turned to the young man and asked him: “Where are you from?” “From Librazhd,” he replied, with his mouth full of bread. “Have you come here to leave?” they asked arrogantly. It seems they had received an order to kill him, even without waiting for his answer.

Without drawing it out and without thinking, one of them fired his ‘Kalash’ (Kalashnikov) at his head. The blood burst out instantly and flowed along the sidewalk like a stream of water. The crowd saw that a man was killed and, terrified, ran away as fast as they could. This young man, apparently, served as an example for the others, so that they would be frightened and leave the port. We were frozen near him, with the face of a dead person, sitting in the public garden, and we didn’t move.

“Let whatever the great God has written happen,” I told myself. Bardhi whispered to us: “Don’t move!” Our hearts were pounding hard like a bird for both young men (one or two?). They were very young! Life is all a hope that must be lived, no matter how it falls, good or bad. The children shuddered at the scene they experienced when they saw the young man from Librazhd bleeding.

Then the executioners left their victim lying on the ground, came to us, and asked: “Where are you from?” They had surrounded us like the yolk in the center of the cornbread. It was a great shock to see the whole family surrounded by the barrels of the ‘Kallash’ rifles.

The previous scene would not leave my sight or mind, and this time the killers had pointed their weapons at us. They had a clear order to shoot. These were the last hours of the red dragon! Out of the seven “heads,” six had been severed. The last one was the seventh “head,” which was also breathing its last.

“From Kavajë,” Bardhi replied. “What have you come here for?” they asked again, and Bardhi clarified: “We came for the hospital and were going to stay for lunch at my uncle’s, whose house is at Currilat, but they wouldn’t let us pass. We are waiting for the road to open, that’s why we didn’t move.” “You want to trick us?!” they expressed suspicion. “No, no,” Bardhi tried to convince them, “let one of you come and see where we’ll go.”

The uncle really had his house there, but we hadn’t set out for him. One of the sampistët, named Bardhyl, who had married his sister in Kavajë, close to us, seemed to recognize us, but we didn’t recognize him because he was masked, and he told the chief: “Yes, Commander, they are from Kavajë, I know them; their house is near my sister’s.”

He truly saved us from them! “You also picked this day to come!” the chief said mockingly. “We didn’t know anything,” Xhevdeti told him. Then he instructed us to go up by the church road, as it was not allowed there. We quickly left and disappeared into the crowd!

Later, after a few hours, it seems the guard dogs had received an order to lower the demand, and then the people rushed and entered the port. The situation calmed down. Here and there, you could see a policeman or soldier, and even they were shooting aimlessly into the air! The crowd had fashioned a stretcher, placed the lifeless body of the young man from Librazhd on it, and paraded him towards the Durrës Boulevard.

That day in Durrës, the sampistët were like the roots of couchgrass. They would appear and disappear, as if by magic. They were the sons of those whose power was slipping away beneath their feet. From that hated government, the youth, boys and girls, fled in exoduses, and their mothers remained cuckoos (widowed/bereaved), with tears in their eyes. Hours, days, and weeks would pass, and those poor mothers would nervously await news of their children, without knowing that some of them became food for the fish at the bottom of the sea, without knowing who had the tragic fate to fall like a fig from the ropes of the ferries! The mothers waited and waited for news from their children, so that their hearts might rejoice, but their tears never dried up; instead, they left marks on their cheeks and in their hearts. /Memorie.al

![“When the party secretary told me: ‘Why are you going to the city? Your comrades are harvesting wheat in the [voluntary] action, where the Party and Comrade Enver call them, while you wander about; they are fighting in Vietnam,’ I…”/ Reflections of the writer from Vlora.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)