By Reshat Kripa

The tenth part

Memorie.al / “Sometimes, when difficult trials fall on a child’s head from the earliest age in the secret recesses of his soul, a kind of scale is born, a beautiful scale, with which he weighs the affairs of this world . Feeling himself innocent, he submitted to his fate without making a sound. I didn’t cry at all. He, who has no reason to be scolded, does not scold others”!

(Viktor Hugo, “The Man Who Laughs”)

SHORTED YOUTH

Dedicated to family and society,

Author

THE PILLAR

In February 1954, we moved to Shtyllasi camp, a village near Levan. We got into the cars and left. After crossing the Koshovica Pass, a new scene appeared before our eyes. A large field and in its background, Sazani and Karaburuni, the two symbols of the city of Vlora. I felt a tremor in my heart. Those mountains made me nostalgic for my city, the pain of my life connected to that city. After a while we arrived at the camp, where we settled in the silos.

Adjacent to our camp was another barbed wire fence. It was a camp for political exiles. The family members of the most prominent personalities of the nationalist forces had gathered there. Their husbands or brothers had either been shot, or had been forced to take the path of exile. Most were noble women who were forced to raise their children in that hell. It made you cry when you saw them in that state. There were very few men. They all worked in a canal, which was far from where we worked.

Shtyllasi was a small village. It got its name because on a hill that was on its side, there was a concrete pillar that, according to legend, once served as a lighthouse for ships. It was said that at that time the coast of the sea, once in ancient times, had been in Shtyllas. It had been the pier of ancient Apollonia, the ruins of which are today located on the hill behind Shtyllasi. We were working in a canal, located near the Vjosa River, about five kilometers from the camp. We had to do this route twice a day, going back and forth. In addition, we had to realize the rate, which was very high. When we returned to the camp in the evening, we did not even have the strength to eat, with all the terrible hunger that tortured us.

* * *

That morning, Sulejman Dizdari woke up with a fever. He visited doctor Isufi. The temperature was thirty-eight degrees Celsius. He gave the order to put him in the infirmary. Nearby was Lieutenant Ademi, who had spoken with Sula the day before. When he found out what it was about, he intervened:

“Now you can’t lay it down. It is in the strength of those who have to go to work”.

The doctor insisted, but he refused. The desolate Sula was forced to go to work. He was walking on his feet. When we got to the canal, there was no power left. Apparently, his temperature must have been too high. My brother, Besnik, proposed that we let him rest by the canal until evening. The rest of us would work harder to achieve his standard. We told this to the guard accompanying us. He accepted.

Lunch approached. It was summer. The sun was burning. Lieutenant Ademi arrived. He saw Sula lying down and ordered her to get up. He got up, picked up the handcart and pushed it with difficulty. When he reached the place where they were unloaded, his powers were cut off and he fell into the pile of dirt. Other carts coming from behind stopped.

– “What are you waiting for, download them”?! – ordered the lieutenant

None moved. Allaman Hysa, Sula’s friend, came forward and said:

– “He is our brother. We do not cover our brother”.

The lieutenant was mad. He gave the order to tie up Allaman. Then he spoke to the others:

– “Continue”!

None moved. As he saw that every order was useless, he went and got a squad of ordinary convicts.

– “Cover it with soil”! – The order was given.

They started throwing earthen carts over Sula’s crippled body. His muffled moans could be heard. This work continued until the evening. Only his head remained exposed. Before we returned to the camp, the comrades pulled his body from the ground and carried it to the side. It was the miracle of Dr. Isufi and his fate that brought him back to life. The doctor, outraged, said to the lieutenant:

– “Not even the Nazis did such torture.”

The lieutenant had to punish him, but he was saved by the intervention of the camp commander. Allamani spent several nights in a cell, handcuffed. He dedicated the following poem to his friend:

MY FRIEND

“They covered you yesterday,

Somewhere in Myzeqe,

Alive in a field,

With earth, oh brother with earth!

Except the head above the ground,

You had no hair,

Contemplating the flu,

All wretched fellows!

And you stood there

Looking us in the eye,

Under and even above,

All two by two.

On the veiled body,

They were busy,

Enough cart full of dirt,

By damn order.

You white as snow,

You felt the pain in your mouth,

To enter the body in the soul,

And silence like a poor man.

In the evening we took you out,

From the pit full of dirt,

Side by side we took you side by side,

Martyr of the new time”!

* * *

One Sunday, while playing chess with Myrtezana, I heard my name, Besnik’s and Sadik’s, for a meeting with the family. The occasion had made it possible for our two families to be together. We approached the barbed wire fence. On the other side, there was Fatushja with Agimi. Sadik’s wife had come with Vjollca. I was amazed by her beauty. It seemed to me like a star detached from the sky. She had the appearance of a heavy lady. The black eyes had a special glow. It seemed to me as if from moment to moment, they would explode. But I also had the impression that behind those eyes, there was a great pain. Maybe for his father.

I talked and chatted with my sister and brother, then, while they continued with Besnik and Sadik with his wife, I turned to her.

– “How are you Violet”?

He blushed a little.

– “Thank you, well”!

– “How did graduation end”?!

– “Very good, but…”!

– “What”?!

From her beautiful eyes, two drops of tears began to flow.

– “Is crying?! Dad told me that you are strong. Even I would have finished the measured by now, but…” – I couldn’t continue any longer. Tears continued to flow from her eyes.

He wiped them with a handkerchief and changed the conversation:

– “I’m sorry! Now I work with my mother. I want to tell you something…”?!

– “What”?!

– “You have to be strong too. These two years that you have left will pass quickly. In Vlora, someone is waiting for you. Dad wrote me everything related to you”.

About Neri, I had talked with Sadik. I had told him how I felt about him. But I didn’t believe that he had told Vjollca. Surprisingly, that feeling had rekindled again. What had been sleeping until now had woken up from those words that Vjollca said to me. But it seemed to me that a deep gap had opened between us. At times, it seemed to me as if this gap had become a vast sea.

I imagined Neri, sometimes as a doctor, sometimes as a financier, sometimes as a lawyer and sometimes as a teacher, while I saw myself as a simple worker, of an agricultural enterprise or construction, of course, if I got out of this hell alive. This seemed to me like a contradiction, irreconcilable. Two people lived with me. One who loved madly and the other, who was afraid of love. Yes, yes, I was the one who was afraid of love! However, Vjollca’s words warmed my heart. They brought hope to a broken heart.

When we parted, I asked Sadik:

– “Who told Vjollca about Neri”?!

– “Of course I wrote it. She is both a girl and a boy for me; she is both a friend and a friend. We do not hold reservations for each other”.

He took out a letter from his pants pocket and pointing at me said:

– “Read it, I got it a month ago. Vjollca used to send me. By reading it, you will understand at what stage our relations are”.

I opened the letter and among other things I read:

“Dad, you are the closest person to me, along with mom. But you are far away and I cannot consult you at any moment. I miss you so much. I want to tell you something that has captured my heart. I love a boy. They call it Brilliance. He was a student of our school, two years before me. Today he is studying law in Moscow. He is the son of an institution director. As soon as he finishes his studies, I think we should get engaged. But for this I also need your blessing. Think about this and answer me. My heart will obey your decision”.

– “I gave him the answer today. I told her that she is free to act as her heart tells her. To be honest, I said these words to him with reservations, inside myself. He is the director’s son, while my daughter is the daughter of a political prisoner. Doesn’t it seem like there’s a whole sea between them?! And why did I say that then?! Because I didn’t want to hurt her heart. Boll is hurt because of me. She is wise and knows how to act on her own.”

I don’t know why, but I drew a parallel between me and Vjollca and found that we both had the same fate.

One Sunday, we were staying at the camp with Myrtezana and Njaziu. The day was beautiful. We were each immersed in our own fantasy. Suddenly we hear that from the camp of internees came some voices singing the Girokastri song; “Stand up, stand up.” We looked at Njaziu. His eyes were teary. That song made him long for his hometown. He was much older than us and it was not up to us to notice him. However, we said:

– “Lord Njazi, you teach us to be strong too. What are you doing like this”?!

– “Because the girocastries here too”?! – He said with a deep sense of longing.

After he was released from prison, he was not given much free time. They arrested him again, this time, allegedly for agitation and propaganda. Died in forced labor camps.

Self-Improvement

By the middle of November, about five hundred prisoners, we were transferred again. I parted ways with Dino, Hysniu and other friends, this time for the entire time I would be in prison. The source and Klito were released after serving their sentence. But the worst part was the separation with Besnik. He wasn’t just my brother. He was also the closest advisor I had. I had shared the most difficult part of my life with him. Myrtezai, doctor Isufi and Sadiku also moved with me. This comforted me somehow.

We rode in five “Skodas”. We were tied two by two. At the four corners of the car, there were policemen armed with automatic weapons. At the top was another with a light machine gun, located above the cabin. A military “Jeep” was driving the motorcade. Behind him came a “Molotov Gas” filled with police. The motorcade continued and at the end another “Gaz” with police closed this caravan. Our car was in the middle of the motorcade

When we arrived in Levan, the cars stopped. They were waiting for something. It didn’t take long and from the other side of the road, six cars with other prisoners came. They came from Kafaraj camp. The cars headed north. I turned my head from Sazani, looked at him longingly once more and said to myself:

– “Goodbye, my dear Vlora”!

Vlora and Sazani were in complete symbiosis. I looked at the island and my house appeared before my eyes. I used to go to the alleys and squares, where I had spent my childhood and distributed tracts with my friends. I could see the faces of my father, mother, Fatusha, Agimi, and of course Neri.

Suddenly they disappeared. As I passed the bend, they were gone from my sight…! Along with them, my Vlora had also left. We passed Fier, Lushnje, Kavaja and Durrës. In Vora, the cars took from the north. We passed Milot, Ura e Zogu and stopped at a place near a forest. The place was surrounded on all sides by police.

– “Who needs to get off” – said the policemen.

We got down and started to relieve ourselves, right there on the side of the road. Two boys tied together, took advantage of the opportunity, got into a thicket and ran away to the forest. The guards dictated. It was stupid, such an action. A drum of crackling was heard in all directions. Bullets whizzed past our ears. A shout was heard:

– “Lie on the ground”!

We lay down where we were. The bullets continued to rain. Their barrage hit one of the fugitives. He fell dead on the spot. This also made it impossible for the other one who was attached to him to escape.

– “Cease fire and capture them alive”! – A voice was heard.

The fire stopped. The guards ran and soon caught him. They put him in the middle and started hitting him who could beat him the most, some with punches, some with kicks. Someone hit him with a rifle butt, while others pierced him with a bayonet. The poor man was screaming in pain. Finally he rested. He was dead. They ordered a pit to be dug and covered them both there, bound as they were. I didn’t know them. They were from the Kafaraj camp. Someone told me that; one was from Kukësi, while the other was from Kurvelesi.

We heard someone keep moaning. He was injured during the battery. The friends called Dr. Isufi, who treated him with what he could.

We got back into the cars and left. We were killed in spirit, because of what had happened. The new camp was inaugurated with two victims. We passed Rrëshen, Burrel and arrived at Qafa e Bualli. There the cars turned right.

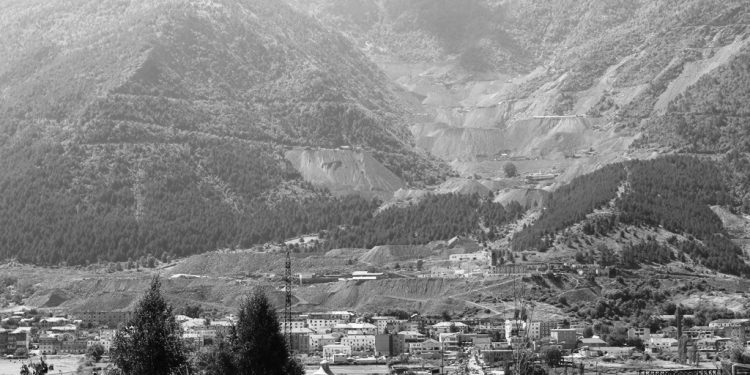

– “They are leading us to the Bulqiza mine”, – said a dibran we had in the car. After a while we arrived at the camp.

* * *

The camp was located on a mountain slope. The silos and the entire mine were surrounded by a triple barbed wire fence. Every fifty meters, bodyguards were set up, where armed policemen were constantly standing. The silos were located on one side of the slope. An inner enclosure separated them from the rest.

The climate was very harsh. The position of the camp against the mountains meant that in the hottest season, there was no more than four to five hours of sun. The rest of the year, he did not see the sun. When we arrived, winter had begun. It lasted almost six months. It started at the beginning of November and ended at the end of April. The temperature in winter was very low. It reached minus twenty degrees Celsius. The long shadows of the ice hung all this season, hanging down to the ground. There was a howling wind that did not let you stick your head out.

The arrival of prisoners continued for several days. We reached over two thousand five hundred people. We gathered in the compressor square, to be divided into brigades. An officer read the names and the prisoners went where he assigned them. I was waiting. Suddenly, my eyes went to the trams, where the chrome was loaded into the cars. There I saw Skënder Janina, the surveyor who had worked on the Vajgurore Bridge. I raised my hand to get his attention. He saw me and motioned for me to wait. I saw him walk up to the officer and start talking to him. After a while I heard my name. I approached and the officer told me that I would be working with the surveyor. Sadik and Myrteza were assigned to work in the gallery.

So I started working as an extra. We give usage quotas in the galleries. It was the easiest job you could do. In addition, the temperature in the gallery was normal, at a time when outside, frosts had begun. This paradise, if I can call it that, ended quickly. Unfortunately for me, lieutenant Ademi, my eternal enemy, came to the camp. As soon as he saw me, he ordered to remove me. He could not forget Vlashuk. I was assigned to the gallery, in a brigade with Sadik. We were the filling brigade. She worked on filling the used galleries with stones, which no longer had chrome. There were ten of us in the brigade.

In June, the father and Fatusha came for a meeting. In Bulqiza, meetings were not held on both sides of the wire, as in other camps. They were made free, inside the gate that entered the camp. After so many years, I was able to hug my dearest people. We talked about everything; we wanted to learn everything, down to the smallest details. Finally, we hugged again and parted.

When we got to the shed, I opened the package they had brought me. Among other things, there was also a suit that Drita had sent me, to wear on the day I would be released. I wore it to try it out. It fit me very well, except for the jacket, which had little short sleeves. As it seems, Drita remembered me as little as she had left me. I folded it and put it under the mattress, so it would stay ironed.

Since the War had ended, it was the first time I had a suit of my own. Until then, I wore those that were no longer made for Agimi or Besnik. Along with the suit, Drita also sent a photograph of a two-year-old child. It was Ora, her little daughter, my niece. I took the picture and started kissing her longingly. I have always had a special love for small children. Even for the most distant and no longer for my nieces.

Behind the photo, Drita had written: “To my brother, I send Ora, like a rubber band, so that, every time he looks at it, he knows that she loves him very much”! I kept the picture, like Christians their icons. Memorie.al