By Aldo Renato Terrusi

Part thirteen

Accueil

Memorie.al / Fiumicino Airport. Alitalia’s ‘MD 80’ plane is ready for flight. It’s Saturday, November 6, 1993. 11.25am. The commander received approval. The flight attendants remind us once again to fasten the seat belt. The two engines are brought to maximum power, while the noise becomes muffled and deafening. Buttons and controls are tested one last time according to flight procedures, the brakes are released, the faster and faster movement begins, the acceleration slams the passengers into the back, the plane takes off. I feel an invisible force lift me up, leaving me suspended in the void. I look around to see if the other passengers have the same feeling as me. Some read, some look out the window, some are indifferent, some barely sit still and some, frozen in their seats, let their fears show. With a wide change of direction, the plane rises in altitude and heads towards the radio beacon of Bari, then straight to Tirana, our destination.

From 10:00 am, we all head to the stadium. It is still early and representatives of the Olympic Committee have not arrived yet. We tell the guard of the stadium to open the gate for us and the small group is directed from the field where they became protagonists many years ago. Suddenly, a ball sprung up, someone kicked it and the others responded. So, seven old men, some limping from arthritis, some with back pain, some with heart problems, kick the field like reeds. Uncle goes to the gate, like in the good old days.

Despite their age, in those few minutes they are experiencing the same emotions as in their youth. But this beautiful game does not last long, because fatigue and shortness of breath are immediately felt. The Albanian Olympic Committee meets in a small hall of the stadium. They call us to participate in the ceremony. To our surprise, the president is a woman: probably someone who has achieved great results in sports. Jakomo is announced as the guest of honor and sits near the leaders.

After a short greeting and a thank you to all those present, all the football players who were winners of the 1946 Balkaniad are called by name: Xhakomo Pozeli, Besim Fagu, Xhavit Demneri, Loro Boriçi, Vasif Bicaku, Pal Mirashi.. .a sad memory goes to Zezen Kiara from Vlora who died the day before.

With the unanimous decision of the committee, the team’s players were declared Albanian “Masters of Sports” and were presented with a gold medal in honor of the past. Jakomo asks him to give a speech on behalf of the whole team. His speech is a poignant evocation of sports and political events, especially in relation to our stay in Albania during the War.

In this regard, the committee requests an official apology to Xhacomino, who changed his name only so that he could stay and play with the Albanian national team. Giacomo thanks sadly, with red eyes and clenched fists to hold back tears. The committee then invites everyone to raise a toast at the bar in front where they could not buy anything due to financial constraints.

I’m sorry, I should have rented, but I couldn’t deny them the pleasure of being ‘the owners of the house’. I toast to Coca-Cola, which right now, at this moment, seems better than any fine Italian champagne. Long live the 1946 team! Long live the sports masters!” On the way back, along the long main boulevard, the ‘Masters of Sport’ no longer feel so excited: who complains on one side, who on the other. That short and joyous game has worn them out.

It looks like we are in an outpatient hospital. Hogging, limping, helping each other under the pretext that they were holding each other’s arms, we finally arrive at “Dajti”. We greet them and tell them that next Saturday, in the morning, we will leave for Italy, so the greetings take on the value of a sad farewell; the small group disperses.

This time we were late for lunch. We call Toli at the Consulate and invite him, on the condition that he shows us a place to eat well Accepts. We go to take him to work and head from “Skënderbej” Square. We enter a tavern, under a portico, well-furnished and welcoming. As usual we are looking for some traditional cooking. The only ready-made and definitely autochthonous dish consists of gathered lamb’s entrails – kukurec. It is a very heavy dish, very special and delicious: I would say not for everyone. Recipes for four strong stomachs:

Wash and dress well a kilogram of small lamb’s offal. 500 grams of liver and 500 grams of lungs are cut, pepper and salt are added and some oregano is added. Eight small sticks are prepared where the pieces of liver and lung are passed, alternating them with some pieces of fat. Hoses are wrapped around the sticks and tied and clamped to form a compact mass. Add salt and pepper to the outside and leave to drain for several hours. The sticks where the chicken has gone are put to cook slowly, taking care not to burn the outside.

It’s almost 15.00 when we get up, full and heavy. We go through the usual road that leads us to Dajti. We sincerely thank Toli for everything he does for us. We leave the meeting for the next day there from 09.00 at the usual place. Tomorrow we have a long and sad journey to Burrel. We happily relax in the comfortable armchairs of the living room in front of the TV, in order to digest the heavy food a little.

It doesn’t take long and we start talking about how Italy, and especially Mussolini, had this feverish desire to colonize Albania. In addition to reasons of a strategic, political, social, etc. nature, that the fascist regime used to justify the invasion of Albania, it is certain that a strong impetus, which later turned out to be quite unfounded, must also have given the reports that came to the Duchess from his messengers. Here is one of the reports sent to him on October 11, 1941 by Zenone Benini, secretary for Albanian affairs, about the assessment of Albania:

“In other areas, some specialists have given positive results; so much so that it can now be considered that the Albanian resources constitute a complex capable of ultimately affecting the order and totality of steel production for Italy. But, as of now, it can be said that we are in front of an iron bearing basin of great importance and certainly superior to all the most optimistic forecasts.

To date, more than 500,000 tons of chromium has been estimated in Albania, and all this leads to believe that ongoing research will continue to yield satisfactory results. The Albanian mineral contains 50 percent chromium oxide, which means that the guaranteed quantities cover the national demand for more than a decade. In the south, in Selenica, the same “Parodi-Delfino” group has in use important plants for the extraction of bitumen, from which, next year, the production of 20,000 tons of pure product will be ensured. Such production, add here also the by-product of the Italian crude oil distilleries, constitutes the foundation of our bitumen needs, which hovers around 70,000 tons per year. Even AIPA has significantly expanded its field of oil exploration and exploitation, and probes are being inserted into the area of Patos, which is thought to be one of the most interesting”.

Of course, if Mussolini had any doubts about the possibility of laying hands on Albania, these information and reports would surely have dispelled him. We think it’s time for dinner, but we both decide to go to the bar for a cup of tea, with some dessert; this will be more than enough for a comfortable sleep.

BURRELL PRISON

The next day at 08.00, as he promised, Engjëll Kokoshi arrived in front of the “Dajti” Hotel. He is waiting for us standing in front of the reception counter, wearing a long blue coat.

“Good morning Angel, how are you”?

“Okay, thank you how did you sleep Today we have to walk a lot? How is uncle”?

“Yes, he’s coming down in a little while, he’s getting dressed. Would you like to have breakfast with us?

“No thanks, I’ll just have a coffee.”

While waiting, we go and sit on the sofas in the living room.

At the same moment, my uncle arrives, nursing, as a result of the “sports performance” the day before. There is even a kidney ache. After greetings with the Angel, we head to the balcony of the bar for a quick breakfast on foot.

“So, before we go to Burrel, we have to pass by my office and then go to withdraw the permits at the Ministry of the Interior.”

In order not to waste too much time and seeing the physical conditions are not very good, it is good that my uncle waits for us at the hotel.

Angel and I, as we decided before, first go to the National Association of Former Political Persecutors to get his credentials and then we go to the Ministry. The office is actually an archive with shelves that go from floor to ceiling – enough to cover three walls of the room – on which are piled hundreds of bundles and files full of data and names”.

While seeing the curiosity and surprise on my face, Kokoshi explains: “Look, Aldo, these are people about whom nothing is known. Unfortunately, there is always an unwritten law of nature that screams for revenge. One should show one’s strength by showing courage and not by expressing suffering, not to complain and not to show too much pity: one should soak in the blood the shame suffered both on a personal and family level.

To think that our tradition is such that when a man gets married, the bride is given a bullet as a dowry by her parents, so that she remembers her absolute submission to her husband. We are still a backward country even from a constitutional point of view. We are still attached to some of our very wild customs.”

Harsh and heavy words that leave me confused and full of bitterness. The Ministry immediately gives us the permits. I was amazed at such speed. And then think of the Italian bureaucracy…! We return to the hotel, the time is almost 09.00. Uncle, Toli and the driver are waiting for us next to the white Cooperazione Italiana Land Rover.

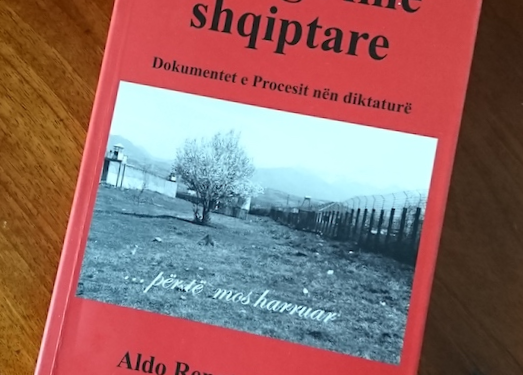

The driver explains to us that what awaits us is more like a mountain car race than a normal journey. Burreli is a town almost 70 kilometers northeast of Tirana, lost among the mountains, made famous in the local chronicles only for the location of its infamous political prison and until now remembered as a terrible and oppressive place. After a first paved view in which you often see streams full of stones, the road becomes winding, often cracked, often full of potholes, against the background of a virgin landscape, as beautiful as it is desolate.

We cross an elegant stone bridge, probably from the Roman era.

The landscape, covered from time to time by Mediterranean scrub that often invades even the road, suddenly opens up into unharvested lawns, verdant scrub and bare mountains. After crossing a rather steep mountain, the road now becomes more flat. More than two hours have passed and finally the first houses of Burrel are visible. We pass the whole city and as soon as we are outside it, we are in front of the infamous prison.

A macabre, gloomy and depressing picture appears before our eyes. It is a low and nearly collapsed building, looking more like a horse stable than a place where human beings have been imprisoned in the past.

An iron balustrade fence separates the ‘stable’ from the rest of the world. Inside a double gate with adjacent entrance hatch for the guard post. They wait for us, we hand over our credentials. We are told that the prison was closed only two years ago and is now just a sad mausoleum for the memory of war crimes.

The entire complex in which the cells are located is about 100 meters long, three meters high and ten wide. It is a masonry building, quadrangular and simple, of an indeterminate color; it does not have the classic tiled roof, but simply a flat cement terrace. From the outside, only ten or so windows, closed with bars, belonging to single cells are visible. The first fence, with rusted open spiral barbed wire, is about one and a half meters high and is ten meters from the outer walls.

The second fence, parallel and at a distance of approximately 20 meters from the first, is formed by a barbed wire in the form of a spiral at the end of a network, cracked in many places and almost three meters high, which surrounds the entire camp and is held in feet of thin half-destroyed reinforced concrete columns. At the edges of the camp, in the form of a quadrilateral of about 200 meters by 100, are four cement posts, placed on metal poles on which large searchlights are placed.

Between the two enclosures are a sort of security crossing and the common grave of dead prisoners. Two guards, in the role of ciceronlt, guard what used to be the place that scared Albanians the most. We are escorted inside the building and as we follow this path, Kokoshi describes different places.

There are twenty or so dark cells, ten on either side, along a corridor occasionally interrupted by railings. Each cell has five floor mats and a small, barred outer slit. A single kitchen was intended for both the guards and the prisoners; there were also six all-aturka bathrooms, made of cement, very close by. In the center of the building are the torture chamber and the infirmary.

“Angel, won’t you tell me why you ended up in prison”?

“Like yours, I was also put through a rigged process, where I was accused of collaboration with the Italians and espionage on behalf of SIM (but it was not true)”.

I wonder how the partisans could accuse Giuseppe of deliberately opening the empty bank coffers to the Germans, when in some of his letters; he expressed his contempt for those hated Nazis. From Giuseppe’s handwritten letter to his sister in Kastelaneta:

Vlora, November 27, 1944

“The German cowards have done everything and carried out all the possible massacres: we have spent days of nightmare and terror, until I even reached the point where I was in danger of my life…”!

From his last days as a free citizen (a few days before he was unjustly accused and imprisoned by Enver’s partisans):

Vlora, January 8, 1945

Since the day of the liberation of Vlora from the partisan troops, who forced the German bandits to run away (bandits in the bad sense), I want to hold on to the hope that you all enjoy full health and that we can hug again as soon as possible defeated”.

“In what period did you meet, Angel”?

“He had entered the prisons of Vlora in 1945 with other Italians – Belucin, Balsamon, Monain, Petrit Velajn – while I was brought a year later. We stayed there until 1949, and then we were transferred overnight here to Burrel. I remember that on the night of the transfer there were about twenty of us, handcuffed in a queue of five people, in a truck accompanied by two cars – one in front and the other behind – full of soldiers armed with Kalashnikovs.

We had made the decision to escape. Time was also on our side. The darkest and moonless night. Some of us had been released from the shackles that were tied with iron wire around our wrists and ankles and we were ready. After a long and anxious discussion, we gave up. It was very dangerous: they would have exterminated us all”. Memorie.al