From Shpendi Topollaj

Memorie.al / With those who have spent a large part of their lives in prison, something strange comes to mind: for everything they tell, they give with the greatest precision, the date, time, time spent in the interrogator, in prison, in the dungeon, the square meters of every environment where they stayed, the articles of the penal code, the weight of the food, the names of friends, guards and other trifles that for the one who is free, are almost of no importance at all. The conditions of isolation, the complete separation from the world around them, not receiving any information about how they are outside, the absurd responsibility and with serious consequences, for almost ridiculous things, sharpened their senses so much that it seems that only their eyes do not saves anything, but they fix a word, a slap, a simple gift from a friend, be it a cigarette butt, so deep in their brain that they never forget it. And the biggest wonder is that even though they lack almost any news from outside the barbed wire, again when they show something, they put the events in such a real background that often even you who listen to them even though you were free, again you didn’t know them. The way they learn new things is both meticulous and mysterious at the same time.

They have an invisible teletypewriter that works day and night at full capacity, broadcasting all kinds of news. Their teletype also predicts important events. He analyzes and draws conclusions, preparing them for the future. So that they are not taken by surprise, not shocked, not disappointed, but also not happy before time. They smell from afar the decisions of a Plenum, the hidden intentions of a law, the signing of an amnesty, the duration of their sentence related to the political situation in the country and in the world.

They, better than any analyst, know how to connect repression or temporary tolerance with the visit of a leader of a great power, say, China or the United States of America. They, of course, hope, but they do not live with vain dreams and illusions. So never lie to yourself. Therefore, speaking to me about the iron resistance of the prison legend Adem Allçit, my friend Ashim Gjoka, who had also been a prisoner of conscience for years, told me one day:

– When a friend of ours asked Adam how many years have you been sentenced, he gave him a philosophical answer: I have been sentenced for a hundred years, I have done a hundred, I have a hundred left. I knew Adem Allçi since he got out of prison. I was introduced to him by my friend Petro Çela, who had been an excellent officer and who had suddenly ended up in handcuffs. They had arrested him demonstratively, right in the middle of Shijak, accusing him of questioning the Party’s policy on the army.

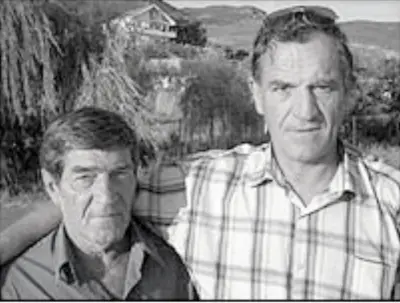

I, who had him as a close friend, knew very well that of all Petro Çela’s loves, the army occupied the first place. In prison, he was closely connected with Adam and this friendship was maintained even after the dictatorship collapsed and all the political prisoners were released. He told me about Adam’s strong character and bravery, about the explosion of the terrible prison of Burrell by him, but Adam himself, no matter how much I asked him, avoided me. Peter’s tired and troubled heart stopped beating very quickly. This caused great pain to Adam.

Since then, accustomed to friends, he became close to Ashim. We drink some coffee together, I teased her, but again you don’t say a word about yourself. When Ashimi told me that striking and wise expression of Adem, I begged you to convince him to give me an answer to what I would ask him, that this was not only a tribute to his two friends Dhori Gërnjoti and the late Sazan Hadëri who had participated together with him in the explosion of the walls and barbed wire of the prison, but also a civic duty to the generations, showing them that even in Albania, there were people who encountered and fought with the communist monsters.

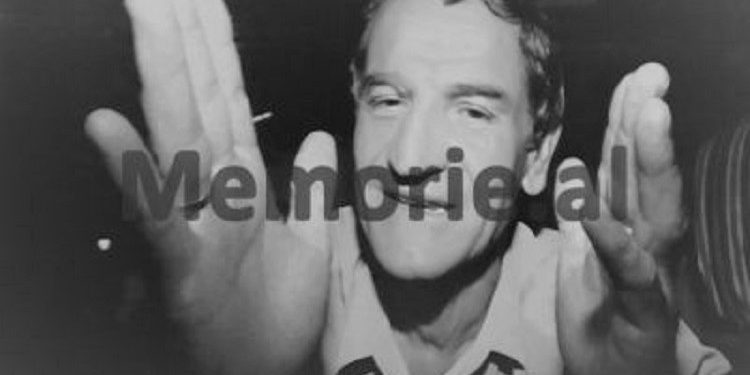

And he accepted. There before me was that fifty-six-year-old man who looked younger than he really was, tall and muscular, like an athletic trainer, with a scar between his eyebrows like those heroes in the Iliad, apparently unfocused, but his whole appearance spoke that in his youth, he had been very strong, determined and energetic.

He left the impression of a strong-willed man who was neither afraid of threats nor subject to flattery. More than a rebel, more than an insurgent, he was enraged by injustice, which was noticeable even now, except that life had “matured” him and made him more restrained.

After inhaling the cigarette once more, when he judged that it was the moment to say something, he made an unsuccessful attempt to avoid the conversation from himself.

– How well you did – he told me – that you wrote about Gjergj Titani. He totally deserves it. He was smart and brave. He always objected to every meanness they did to us. He inspired us and others.

– That’s right, – I intervened – but today I want something from your life. For example, where and when you were born.

– In March 1942 – you couldn’t stand Ashim.

– In the village of Viçidol near Old Tropoja. – added Adam. – But my origin was from Batusha in Kosovo, a village near Gjakova. Serbia followed us and we came to Albania there from the twenties – thirties. We were six children, five sons and one sister.

I was the last one. I went to seven-year school in Tropoja. Then they did not give me the right to continue, so until 1962 I was engaged in agricultural work at home. In Kosovo, we were in good economic condition. In the family, we grew up with a feeling of hatred for the communists who, during the war and a few years after, made the Serbs the master of the house here and left Kosovo to them.

But even the Albanian communists did not like us. The first blow was taken by the family of the sister who is married to Idriz Hoxha. He and his two brothers, Hysen and Abedin and their father Zenel, who was a friendless man, as well as my sister’s son Beqiri, ended up in prisons. In this situation, I was raised as a soldier and taken to the Fifth Infantry Brigade, in Gërhot, Gjirokastra.

After four or five months had passed, my brother Elezi, who was six years older than me, came to see me. Without further ado, he tells me that he had come to take me with him, as they had decided to escape. We would go live with our people in Kosovo. We made up a lie and I took a few days off.

We stayed at home for two or three days, and after getting old once again, we let Elez and I cross the border. On April 4, 1963, we left. We knew the place covered with chestnut trees very well. At twelve o’clock in the day, at the sixth pyramid, in Pigeon’s Neck, we crossed the border and stepped on the mat. We didn’t have any obstacles until we reached the small town of Panashet, which is near Gjakova and not more than an hour and a half away from the border. We had nothing to support, so we went straight to the militia. We told them that all the men of our sister’s family had been imprisoned and now it was our turn, so we left.

We know if they believed us, but after asking us some tough questions or rather that they knew without asking us, such as who is the Head of the Internal Affairs Department in the district, etc., they took us after three days and nights of investigation to Gyurakovs in Peja, where the concentration camp was and where they left us for two full months.

Here you find people of every cast and nationality. Soon after that, they called us and asked us where we wanted to live. We didn’t have work in any country, so we said we would settle in Kosovo. Okay, they told us, we will take you to a favorite place and after they tied us up and threw a blanket over our heads, they took us out to Qafë Morinë in a car. We couldn’t believe our eyes. Communists, there is no devil who understands them. They fight with each other allegedly over ideological problems, eat like dogs and then, without waiting, agree on beauty. They did not mistreat us on the way to Kukës. When we entered the Department of Internal Affairs, where Mayor Ndue Gjini, a really bad man, was waiting for us, we saw that my mother and three brothers had also been arrested. I didn’t put anything in my mouth for ten days.

I thought and said to myself that I had passed a difficult test; I had not shown there that I was a soldier because they would bother me with questions that I would never answer, I had risked my life and that of my family, I had lost my future, but I had gained one thing; I had proven that I did not know fear, and this increased my conviction that I could hate communism even more.

They were evil, so they should be afraid of me. I knew that from now on, if I remained alive, I would have no other weapon but courage. And this gun never let me down. The trial took place in Shkodër after nine months. I did not tell you that I was taken at the border related to May 29, 1963.

We were judged by a military court which, with decision No. 14, on February 7, 1964, found us guilty, sentencing me to twenty years of imprisonment, and my brother to twenty-five. From Shkodra they took us to Laç, where they were working to build the Superphosphate Plant. I stayed here for a year and a half. When I compare it to the places where I served my sentence afterwards, Laçi seemed much easier. Then I was transferred to Rubik.

There was also work, but it was a real horror. Horror in every way. The six hundred prisoners were the slaves of the camp commander, Nazi Colonel Bajram Korvafa from Kuçi.

– Write this name. – Ashimi intervened – There were many who did their duty and we have nothing to do with them. But for those who exceeded the rights given to them by the law and who saw and treated us as guinea pigs, we have no reason to protect them until we don’t mention their names.

Adem spoke again:

– I always declared two things: I don’t love P.P.SH. – In, and for you I will never work. Then they massacred me. It was not difficult for them to do this. It’s morning. Five o’clock. The bag dropped. I didn’t get up right away, according to them. The officer insulted me. He insulted me severely. I couldn’t stand it and hit him. Immediately the police came in and tied me up.

I have had this sign since then. They put the irons on me. I had become a beast. It was the accumulated milk during all that time. I pulled my hand out of the handcuffs, leaving the skin on those bars. With my bare hand that was bleeding, I hit two policemen. I fell with handcuffs on my head. I didn’t know what to do anymore. They fell unconscious. Then many policemen and soldiers came. They tied me up again and left me in the dungeon for a month. Dungeon! Even today I am horrified when I remember it.

Even the animals when they are locked in cages, I think they suffer a lot. What about the man? That man is tired and tortured by thoughts, worries of the soul. Hunger and cold are also tolerated. But humiliation never. I was over a hundred pounds. Now I could see that I was losing weight. I should have done it. Dead and unburied. Or rather, buried alive. Oh God, don’t let me forget!

The new day of punishment came. I will never understand this. To be sentenced as a young man to twenty years in prison and they are unhappy to give you another eight. Eventually, I made up my mind. My life here was over. From now on I lived in vain. So much to suffer. This was my fate and I had to obey it.

They put me in the dreaded auto-prison and one December day in 1965, I found myself in the yard of the Burrell prison. Here I found other beasts. They screamed and cursed non-stop. They checked me minutely, just like that, in vain, except for force of habit, to see what I would have. I used to come from prison and go to prison. How is this life of mine?

And don’t remember that I didn’t want him, and I didn’t have my youthful desires. But she, I don’t know what was wrong with me that kicked me. Burreli, what’s up? I had heard about it. But it is quite different with listening. When they put me in the cell, I saw old men. Not old, but outdated. I can even say that I saw corpses still wandering in this real hell.

They had once been young, smart and powerful. Now, just see them. They were ready to suffer. How man becomes, or rather, how they disfigure man. There were about twenty people in one cell. There were prison veterans there. I was still a pioneer before them. They are all intellectuals. Men who used to mind others. But now they didn’t even need them for themselves.

I was received very well. You could see that they felt sorry for me. We got used to each other, just as I got used to the harsh conditions of life there. How strong the man is. At first I found it difficult. Then I taught them something and started to urinate in their eyes in the bucket they had set up for this job. There was a schedule in the bathroom. Twice a day. Think, I’m sorry about that, when you get sick. You will defecate right there in front of those men. This made our punishment even more severe. For the cistern, in the dacha, say also for the urinal, we put a cardboard box on top of it so that it wouldn’t smell, and we were only allowed to empty it in the morning. Even our noses seemed to get used to the bad smell. Even for ventilation, they took us out twice a day. We never learned why they didn’t take us out at all when a senior leader passed by. I don’t know what danger we posed to them.

After a year, in 1966, I was sent to prison 313 in Tirana, without knowing why. They left me for three months and apparently they regretted it; they sent me back to where I was, in Burrel. Here I met two young prisoners. One was Dhori Gërnjoti from Korça.

– I have known him – I told him – there since 1964. He came in front of the Officers’ school dressed in sport and asked me; that I knew where the Boxing team of “Partizani” lived. He was a pretty boy. Brun. Cropped. And he seemed very wise. I had heard about him, but especially about his father, Rafael Dëshnica, a big name in the thirties.

– I too – Ademi took the floor again – I had known him since Rubik. Then, together with Elez, my brother, they took them to Elbasan. The other one was a boy from Fushbardha, who was called Sazan. Sazan Hadëri, who had tried to escape from Laçi camp,. Both were sentenced to twenty-five years, after they wanted to escape from Albania. They were brought to Burrel on June 16, 1967. They put us in a room, a room we called the youth room. We felt somewhat good, but for the hell of it, they brought us a shepherd from Korça, convicted as an ordinary, but who was a spy. The name doesn’t matter…! Shame on him. Once, as we created trust in each other, we agreed to organize the release from prison.

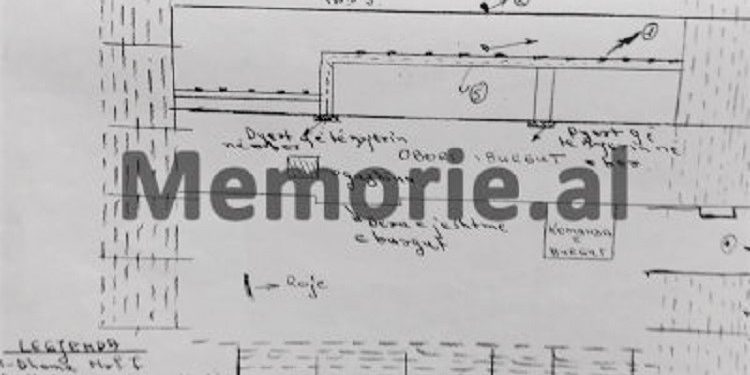

I am not able to say that at this moment, this was the only way out that was imposed on us, or we were brave, or we were crazy. Perhaps, great desperation makes you choose this almost absurd option, which summed up the only way out, bravery, and madness. We discussed at length and left it for the next day at the time of the appeal. I previously wrote a letter addressed to Enver Hoxha. I will never forget her lyrics: “We are a group of young people who tonight have decided either to be alive and free or to die, but we will blow up the Burrell prison”.

I am not saying the other words. I cursed heavily. I put the letter in the envelope and wrote the address on it. When the next day at dinner, at 7:30, the officer of the guard came to make the appeal, with one hand I handed him the letter, with the other I hit him hard with my fist. I heard that he said: “Adem, I am also Albanian and I remain in your allegiance”. There was no time to think too much. I grabbed his hat and put it on his head. I also got the keys. Dhori and Sazani dealt with the other policemen.

I walked down the hall and opened the door to the inner courtyard. I knew it was guarded with armed guards, light machine guns and searchlights. Surprisingly, there were only three of us in the yard. Dhori and Sazan came out with me. I don’t know what happened to the others. That officer’s hat could not help me. The soldier saw us and fired a long volley of machine gun fire at us. I climbed onto the terrace like a cat.

– Like a tiger! – corrected Ashimi.

Adam laughed:

– Okay, like a tiger. And I extend my hand to Dhori e Sazan. We were being shot at from all four sides now. I forgot to say that I kept my reason and self-control enough to turn off the interior lights by removing the fuses. Confusion was created. By the time we were jumping from five to six meters in the outer courtyard, the bullets hit Sazan in the body. He fell dead over a canal. I could not help him. There were other fences with barbed wire running through them that were unrelated to the fuses I removed. The barbed wire was held on some concrete columns. I jumped from one column to another. Of course, today, I can’t do that.

Evil, trouble makes you an acrobat. Dhori and I left the prison. But it was quick to rejoice. We ran until we entered the vineyard, but found ourselves surrounded and pursued by numerous forces. I heard Dhori groaning and said to me: “Go on, Adem, I can’t do it anymore.” I was wounded in the leg.” Alone, gasping for breath, I walked through the darkness. I did not know the country at all.

I walked freely. I stopped somewhere because I was feeling very thirsty, to drink water in a frog pond. When I bent down, I saw that my shoulders were bleeding profusely. Bobo, I said, and I needed that. But fortunately, I don’t even know how it happened, but it must have been a blind bullet that didn’t pierce me further. I have the sign here, but it doesn’t matter that this is not the place to show it.

I walked for three to four hours until I entered a corn field. In the distance I heard the sound of helicopters. They had started from Tirana. I understood that the explosion of the prison from our side had shocked the leadership too much. The whole of Burrell’s Corps, even the women and children, were on their feet. Around two or three o’clock they caught me. When I woke up, tied to the tank, I was exposed in the center of the city and I heard what they said about me in front of the people who were happy to see me in that sorry state. How people become at once. Individually, they can be very good. But sometimes, when they get together, they go into hysterics.

I don’t know where this comes from. Maybe out of fear. Perhaps from collective servility. Maybe from something internal inherited from ancient times, from the gladiator arenas… I don’t know. Besides, I know very well that as they were torn to pieces by whoever caught us, so now whoever screamed the loudest against me. In the dungeons of the Internal Affairs Branch in Burrel, the deputy ministers himself, even the minister, came and shouted at me: “Show your friends!” They didn’t give up on me. I already said: “We had no business with others. We wanted freedom and we went in search of it. Everyone knows what they are doing. As if he himself answers for what he does”.

The trial took place in Burrel on August 19, 1967. Sentence: death by firing squad. I expected this. I hoped they would spare Dhori’s life, considering the family he came from. As for the young age, they didn’t even want to know. I was more upset about him. My life seemed completely meaningless. In the last word, Dhori in a calm voice, sitting down from the wound on his leg, said: “Yes, please, spare our lives.” I directed you, without permission it is understood: “Rest Donate! Better to kill us, because there is no man who starts from scratch”.

– No, – Ashimi waited for him – you said: Kill us as soon as possible, because we can’t start all over again.

– It’s the same. Not Ali Hoxha, but Hoxha Alia. – Adam got angry – In any case, we ended up twenty-eight months in the dungeons of the Internal Branch, waiting for the answer from above. The Supreme Court upheld the decision. We continued to be tied hand and foot.

That was the rule; it was bad when we ate bread, but worse when we went to the bathroom. One policeman held our rope, the other pulled down our pants. We also had many visitors, officers, policemen, civilians who came and saw us, like seeing a rare animal. They wanted to know how they could be the ones who broke the filthy prison. I can’t lie, because God kills me.

Even here there were good people like…

– Farudin Shehu from Tepelena. – Ashimi quickly reminded him.

– Yes, Farudini, a very human guard. So human, that he let me talk to Dhori. Don’t worry, I told him. Once the husband dies. That’s how it was, until one night at eight o’clock some men came to the door. I don’t remember how much. Some had come from Tirana. One addressed us: “The Presidium of the People’s Assembly took into account your request and spares their lives.” I had not made any request. My request was the letter I had sent to Enver Hoxha before the prison explosion.

I can’t tell you that I was happy that my life was spared. In this respect I was completely numb. Another thing made me happy; that the dream I had the night before turned out for me. You may not believe it, but that’s how it really felt to me. The dream, there in the dungeon where I was tied by the hands and feet, I almost never saw, but that night I felt as if I was in a mountain. Ali Maliqi appeared in front of me, who had been taken by the security forces in Elbasan, where he was serving a long sentence.

– You have done – added Ashimi – almost all the punishment. There was only one month and four days left to do.

– One month and four days. Neyse, he had been, if I’m not mistaken, an exponent of the National Front.

– No, – Ashim couldn’t bear it – don’t confuse them, of Legality.

– Yes, of Legality. Aren’t they the same?

– How are they the same?

– Agreed! I was standing in front of this man. I was covered in soot. Coal, how do you say it? I washed there and the soot was falling. I got clean all over. I couldn’t stand it. Donate! – I called, – our lives will be spared. We escaped. However, we did not get away without anything; they returned it to us by another twenty-five years. Now we had avenged the prison of Burrell. Here an unforeseen disaster occurred. On November 7, 1968, Najaz Demir was brought in as prison commander.

– Even this one – Ashimi hastened – mention his name.

– To mention that he was a real criminal. During the war, he was the deputy commander of the Kosovo Brigade. That’s what they said. But as a heartless person, you couldn’t find your friend. It completely ruined our lives. We have cursed him with all our souls. I always wondered how there could be such people in the world. In 1973, when they were looking for strong guys to work at the Ballsh Plant, they chose me. But I laughed and swore not to work, because it seemed to me that I was serving them. They could keep me in prison, but they could not force me to work.

I have never been lazy about my work, but that’s how I felt somehow with personality, I seemed to be independent and dignified in front of them. Shqip, that’s how I challenged them. Even when I was on hunger strike. They kept me for a year and when they saw that they could not defeat me, they sent me back to Burrel. In 1985 (they never forgot me), I was deported to Spaç. I didn’t go to work here either. I cracked them. They felt insulted and powerless.

They provoked me, punished me, but also protected me. The head of the Rreshen Police also tried, and because I couldn’t stand it, I hit him in the middle of the camp, in front of all the prisoners. Maybe twenty policemen rushed at me. What didn’t work for me? Then they left me to die. Only when they saw that I was not one of those who die easily, they took me to the hospital in Tirana, where I stayed for twenty days, one for each policeman and again in Burrel.

Until April 30, 1990, when all political prisoners were released. I went out together with Gjergj Titani, who, as I told you at the beginning, is worth writing about, not about me. Except I entered at the age of twenty-one and was leaving prison at the age of forty-eight. What was left for me? I was like everyone else. But now enough, that I became talkative. I’m tired of you too.

– Not at all, Adem Allçi. – I told him – I listened to you with great interest and for everything you told me, you increased my respect and honor for you, for your sufferings, for your youth that you did not enjoy a day, for your courage and endurance heroic, for the act of exploding the prison, a symbol of horror, transforming itself into a symbol of resistance and bravery.

Adam ordered another glass of brandy and laughed in an indeterminate way. His face more than ever resembled that of the Homeric heroes, who have just emerged victorious and are ready to start a new battle. I cleft it between the eyebrows, as if it now caught my eye more. His vision cannot be focused.

His chin is slightly protruding as if he is getting longer. He stands majestically before me. Just as he stands alone who has won many battles, not with an army, that is, with the weapons of others, with the river blood of others, but quite simply; with his arms, with his courage and manliness, with his patience, and above all, with his hatred.

For a moment, that man’s face took on a softer look. He laughed differently. He laughed as a mischievous child laughs and ended this conversation:

– Thank you, my friend, for trying to write for me. Sorry for talking too much. But I can’t stay without telling you a secret; know well… I haven’t told you everything…! Memorie.al