By Uran Kalakulla

Part Twenty-Eight

Nazism and Communism

Memorie.al / Nazism lasted 12 years, while Stalinism lasted twice as long. In addition to many common characteristics, there are many differences between them. The hypocrisy and demagogy of Stalinism was of a more subtle nature, which was not based on a program that was openly barbaric, like Hitler’s, but on a socialist, progressive, scientific and popular ideology, in the eyes of the workers; an ideology that was like a convenient and comfortable curtain to lie to the working class, to lull the sharpness of intellectuals and rivals in the struggle for power.

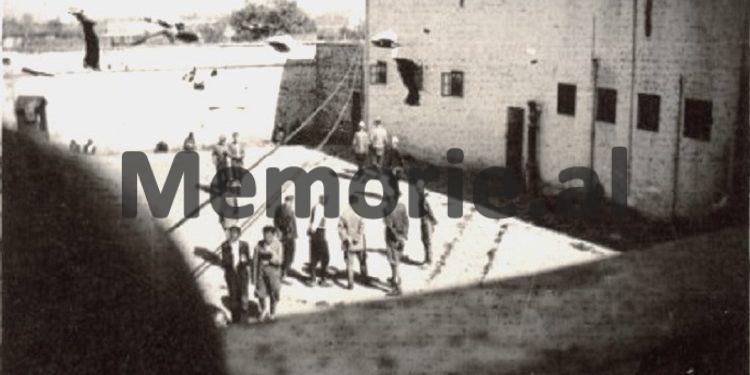

One of the consequences of this peculiarity of Stalinism is that the entire Soviet people, its best, capable, hardworking and honest representatives, suffered the most terrible blow. At least 10-15 million Soviets lost their lives in the torture chambers of the KGB, martyred or executed, as well as in the gulag camps and others like them, camps where it was forbidden to correspond (in fact they were prototypes of the Nazi death camps); in the mines in the ice of Norilsk and Vorkuta, where people died from cold, from hunger, from crushing work in countless construction sites, in the exploitation of forests, in the opening of canals and during transportation in leaded wagons, or in the flooded barns of the death ships.

Continued from the previous issue

Rremë Xhakoni (that was my friend’s name), was an honest man, originally from Ishmi, an ardent patriot and, if I am not mistaken, a supporter of King Zog. His death was the spies, whom he not only hated, but had killed many of them, with all his might. And he had as much power as an ox. For this work, Zata had been taken to Burrel, where he had spent years with prominent intellectuals, from whom he had gained a passion for knowledge and, especially, for philosophy, even though he had not had much schooling and did not know any foreign languages.

But, like any beginner in the field of knowledge, he had a great adoration and passion for the “mother of knowledge”, that is, for philosophy. And it does not matter if, when speaking philosophically, he confused Socrates with Aristotle and Kant with Schopenhauer or Spinoza with Bacon. Even less so when, he treated all of these with the language of the peasant of Central Albania.

And perhaps, precisely for this, among other things, he was quite charming and everyone loved him. But, because he spoke openly and was very critical of Marxism, I avoided such conversations with him, with the only excuse that I didn’t understand philosophy at all, so I was a dunce in that field, since my passion, as a former language teacher, had only remained the grammar of the Albanian language.

Rrema looked at me with suspicion when I spoke to him like that. Yes, what could I do? I had made up my mind to keep my mouth shut about such a field, because I knew that, not from Rrema himself, but from those who were eavesdropping on us, Plato’s “Republic” would end up with the operative, like the American Republic of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

While we were sitting in that “cultural hall”, each at his own work, facing Rrema, the door suddenly opened and the operative entered with a rush. According to the instructions we had been given, not for the operative, but even for the most ordinary policeman, you were required to stand up as a sign of “respect.” I quickly hid my manuscript without the operative seeing and stood up, just like Rrema.

The uninvited guest approached Rrema and, during their shared conversation, looking at the thick volume of Mao’s book, he spoke to him:

– “Hey, Rrema Xhakoni, why are you coming in?”

– “What’s wrong,” Rrema replied, “When there’s nothing else, I’m doing this.”

– “And how does it seem to you, O Rrema?”

– “By God, I tell you, Mr. Operative, I don’t really understand Marxism, but I’m trying…! To me, Marx and especially Engels seem easier.”

– “What?” – the Operative replied, as if surprised.

– “That’s how it seems to me, sir.”

– “And why, O Rrema?”

– “Anyway, those two Europeans, well, closer to us, while Mao is Chinese, far ahead of us, and this is the first time I have come across his book.”

Rema’s reasoning seemed to grip the operative. Had he really grasped the “usefulness” of Rrema, this “security intellectual”? I believe not. And Rrema continued:

– “This talk about dialectics is very confusing. Oh, I learned dialectics in my youth from Hegel, and then from Marx and, especially, from England…”!

It was clear that Rrema was trying to attack Mao’s Chineseness, holding fast to the beard of the fathers of Marxism. And the operative, no matter how much he had studied “party school,” was unable to distinguish the differences in interpretations between the “fathers” and their Chinese “grandson.”

– “Yes, where did you learn all these things, O Lie, with all the schooling you have had”?

– “Why, don’t you know that I came here? I came to the Burrel Prison, where our heads are not raised in the field of knowledge, sir. Those who have entered the universities of Europe, we know philosophy like the back of our hands”.

– “Okay, okay, O Lie”, – the operative replied, not knowing what to think or what else to say. And he continued on, pursuing the goal of getting the information he needed.

– “And with Uranus, do you ever talk about such things, O Lie”?

Here I intervened quickly, not giving Rrema time to speak and, saying to myself: “Ah, you son of a bitch, you’ve taught me the name and you want to trap us both at once”? And in a loud voice, I said to him:

– “Do you know how it is, Mr. Operative? Rrema is telling you that he is strong in philosophy, while I don’t understand anything about that business. I am strong in Albanian grammar, which Rrema doesn’t tell him at all. So, we have no points in common in the field of knowledge. So, I believe it was more than clear: between us we only communicate ‘good morning’ and ‘good evening’ or ‘good night’, or, when we meet near the kettle, whether the dish had more or less pork fat today. Or not, O Rrema”? I returned to my friend, giving a clear signal.

And Rrema confirmed what I said. Thus, the operative, encountering our precise defense, felt himself broken and, to our delight, left the room. But this momentary pleasure did not last long. Not for Rrema, but for me, because, when I was leaving that “library”, at the end of the corridor, right at the door of the Technical Office, the operative was waiting for me, who, as soon as he saw me, spoke to me:

– “Someday I will call you to talk about something together (below, for the sake of the reader, I am “translating” his speech into literary terms).

I responded to his words:

– “I don’t know why we can talk together, Mr. Operative”.

– “Why, don’t you feel like talking together”?

– “By faith, not that hard, but I can’t help it, because I’m here where I am. So, even if I didn’t want to, you have the police, who will grab me by the scruff of the neck and throw me in front of you. And, since that’s how it is, then let’s talk right now, right here where we are.”

The operative opened the door of the Technical Office, told those inside to come out and invited me in. To be honest, it felt like something had fallen on my head. That office had a bad reputation throughout the prison camp. It was really called the “Technical Office,” meaning it dealt with organizing the work for the construction of the factory, the division of brigades, work standards, the miserable salaries that were paid for them, etc. But it was also a “nest of wasps,” because the head of that office was the operative’s first assistant.

Being a prisoner like the rest of us, it was a hotbed of intrigue, a center of espionage and many other vile things. For the political prisoner, that office was like the Internal Affairs Department for the citizen outside the prison.

What weighed on me the most was that, entering that office alone with the operative, all those who had been there: the head of the office, the brigadiers, the standard-bearers, the accountant, etc., who knows, they couldn’t think of me, of this secret conversation with the operative. The other guys around. And that weighed on me a lot. Yes, what could I do? I gathered myself and went inside, thinking that, when the conscience is clear, every thought of others or every doubt of theirs, if not immediately, will eventually dissolve, like salt in water.

Because, after all, the greatest judge of me, I called my conscience. The operative took a seat at the head of the table, in the place where the head of that damned office usually sat. I stood in front of him, as had happened to me repeatedly in the investigation (and to me and all the others who had gone through the ordeal of investigations), before going to court. I lit a cigarette and waited for him to speak. And he spoke:

– “You are not behaving well”.

– “In what direction, Mr. Operative? I know that I adhere to the implementation of the regulations here point by point”.

– “Leave them. You know what I mean. I told you that you have a very bad attitude”.

– “I, Mr. Operative, do not know what you call a good or bad attitude. Can you explain it to me? That I maintain an attitude that seems to me to be completely fair, regular. Where did the flaw in my attitude lie then”?

– “Let me tell you, bluntly”.

– “That’s exactly what I’m asking for, to know how to control myself.”

– “You’re agitating against the Party and the people’s government.”

– “I was once convicted for this. I believe you’ve seen my file, which should have information about why I’m here. So, as the Albanian proverb goes, I got burned badly by the porridge and I’m blowing on the cob.”

– “You showed a kind of gaiety in a group of your friends, like those of ‘Hosten’, but with hostile intent.”

– “Can you tell me what gaiety I showed?”

– “You told me that, in America, a man who lived alone kept seven turtles at home and, when the judge, who was sentencing him to seven years for a violation of the law, this man said during the trial: ‘Okay, what was the punishment for, but what was the fault of the seven turtles, which would die of hunger, because there was no one left to take care of them’. And the judges released him.”

Hearing this accusation, I laughed lightly and turned to the operative again:

– “Is that all I said? And is this a new political crime against the party and the government”?

– “You may be surprised and think it’s a joke, but what you said is a double-edged sword”.

– “I understand, Mr. Operative. What else did I say”?

The operative, without thinking further, added:

– “You said in the presence of so-and-so, so-and-so and so-and-so, that the only leader of the socialist camp who has understood that the path towards Western social democracy must be changed is the leader of Poland, Gomulka”.

– “What else”?

– “Why, aren’t these enough for you”?!

I pursed my lips again and addressed him:

– “Believe it or not, but I am hearing for the first time in my life that joke you mentioned. And it is not a double-edged sword at all, but a piece of nonsense with horns! That joke was very badly invented, certainly by some malicious and dog-hearted ignoramus. Such a joke makes fun of American justice. But I have a completely different opinion about that justice. And, likewise, about America itself, which, I tell you straight to your face, I love very much, like my second homeland.

I know its history, its literature, its culture, more or less even the customs and psychology of the American people well, because I read a lot about it before I went to prison. Consequently, I have a thousand and one arguments to praise America and not with a joke with seven turtles.”

As you can see, I was careful not to mention American philosophy, because I had said in Rrema’s presence, in the culture hall, that I had no knowledge of that discipline at all.

– “And about that other statement about Gomulka’s ‘backsliding’, let me ask you a couple of questions.”

– “What questions?”

– “Yes, Mr. Operative, when you check, as everywhere, even in my bed, as the only place where I sleep, did you find any radio receivers?”

– “No,” he said, surprised.

– “Very well. But Radio Tirana, which we listen to through the only loudspeaker you have installed inside the camp, has it ever given news of this nature about Gomulka?”

– “It seems not to me. Yes, what do you mean by this?”

– “But ‘Zëri i Popullit’ or ‘Bashkimi’, has it written anything about Gomulka? You, of course, read the press regularly, while I hardly read it at all, because I don’t have time and I haven’t subscribed to any kind of magazine or newspaper, because I haven’t seen it.”

– “No,” – said the operative.

– “Then, where the hell did I find out what Gomulka is doing in Poland or, where the hell is he, which I don’t care to know at all”?!

And I continued on with more determination, with an anger that was growing in my soul and I could barely contain myself.

– “Look, Mr. Operative, the names you mentioned, among whom I dropped the ‘bomb’ on Gomulka, I know very well who they are. They are your agents here in the camp. And I have not yet thought of inventing such things for them, which, I think, would be better if I told you directly than to them, because you would take exactly the words I say, while they would add and distort them according to their appetite, to please you as much as possible.”

They make up all sorts of lies, how and how to gain your sympathy and then come and ask you for a reward, for some easier job in some warehouse, a normist or who knows what else. They are vile liars and dirty people, without character. And, you should know this very well. They and their friends. And let me tell you something else finally. I almost know your entire network of spies. Shall I tell you by names”?

In fact, I didn’t know them all, but I blackmailed him. And he ate it, because he reacted immediately:

– “No, no, there’s no need”!

– “Then please leave me alone because I don’t deal with such things. I only look after my own troubles and my mind is only on my family. You who check, necessarily also my letters that I send once a month to my family, I believe you already know what concern and compassion I have for them. And I have no intention of making political agitation here. Secondly, don’t you see the composition of the majority here? The majority are simple peasants or workers, who don’t know why they are here. And the majority of this majority is almost illiterate, so much so that they don’t even know how to put their signature on the pay slip when they receive those few ALL.

Take the pay slip and see how many fingerprints there are on its lines. Well, I am an intellectual and I don’t do politics with illiterate people. Here’s one more reason. And please leave me alone. I deal only with linguistics and literature. These are my only trades. I have left politics to you, the commissioner or someone else who has the trade. And I want to believe that with that we have clarified everything very well together, once and for all. Therefore, please, once again, leave me alone in the great trouble that has befallen me and my family. Now give me permission to leave, because I heard the bell for the evening tea and I have nothing to do with the piece of bread that is left”.

The operative did not speak anymore. He nodded in approval of my departure and I left that cursed room and headed for the line in front of the tea kettle. There, several prison comrades, known or unknown as yet, who had been eavesdropping outside the window, approached me and hugged me lovingly, saying many kind words to me about how I had coped with that very unwanted dialogue with the operative of that camp.

I felt that my previous anger was gradually easing and a great calm was taking over my soul. On the other hand, I had the illusion that, from then on, the operative would leave me alone and would not bother me anymore. But I was wrong. Because, after a few days, it seems that the anger that had come out of that argument as clean-shaven, the middle of winter, in the underground dungeons, where the winter cold and humidity had set up their “Central Committee”, for a month in a row. / Memorie.al