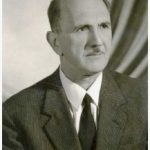

Ejëll Çoba

Part six

Memorie.al publishes some parts from the memoir of the author Ejëll Çoba, the well-known intellectual from the city of Shkodra, a sucker of one of the most famous families of that city, who after graduating from the University ‘La Sapienza’ of Rome in In 1932, he returned to his homeland where he practiced his profession, pursuing an administrative career, as ‘Dottore in Giurisprudenca’ and then for several years in the senior state administration, where he also occupied the period of occupation of the country, (1939- 1944), where he held several senior positions, as Director in the Ministry of Justice, Secretary General of the Council of Ministers, Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, etc. His arrest in 1946, (together with his brother, Kelin) accused of participating in the ‘Postriba Movement’ and after a long investigation in Shkodra and Tirana, was sentenced to 25 years in prison, of which he suffered a full 23 years and five months, and five days in prison, in the terrible camps of forced labor, all the way to Burrell Hell. Ejell Çoba’s unknown memories, which come with a preface by his fellow citizen, the well-known writer, Zija Çela, present to the reader a panorama ‘painted with the brush’ of pain, which gives details and details about his sufferings in the camps. of the prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, as well as other accomplices, known and unknown names, such as: Father Bernardin Palaj, Guljelm Suma, Syrri Anamali, Ramdan Sokoli, Cin Serreqi, Father Karol Serreqi, Father Filip Mazrreku, Hamdi Isufi, Hafiz Ali Kraja, Beqir Çela, Musa Gjylbegu, Asim Abdurahmani, Kolec Deda, Nikoll Deda, Felatun Vila, Gjush Deda, Sali Vuçiterni, Emin Bakalli, Qani Katroshi, Sali Doda, etc., as well as some names of investigators, guards, State Security officers, such as Fadil Kapisyzi, etc.

Continued from the previous issue

Imprisonments

Memoirs written from August 1973 to the end of December 1977

Only extreme things can be tolerated

Count Rober de Montesquieu

There in prison I met many friends and comrades, whom I had not seen for almost three years, and from them I learned many things that had happened during those 7 months that I had been isolated.

The fact that there was a great desire between friends and acquaintances to talk to each other, as well as the uplifting humorous atmosphere of hope that reigned among the prisoners, created a kind of euphoria in me, and I almost forgot that I was going on. of the court, if it were not for a lover, who with his long words came around, would have made me realize that the communists could not be trusted, and that not only could they sentence me to death, but they could also I was executed because, as Fishta says: “there is no faith”.

After three or four days, Hamdina and I were escorted to court. We heard the prosecutor’s claim. Petrit Hakani, as a former Flemish teacher who did not know how to draw conclusions, spoke at length about the politics of the time of the occupation and about the Movement, without being able to bring any evidence of any of our actions that would have harmed any Albanian and concluded You demanded my and Hamdi’s death sentence, without mentioning either our surrender or the amnesty law of September 1946.

The next day, May 28, 1947, the court sentenced us to death on appeal. Of course, this decision surprised me and was a clear proof that for me and Hamdina, the amnesty of September 1946 would not apply to those who surrendered. Others, such as Salih Vuçiterni, Xhemal Naipi, Shefqet Muka and others, were sentenced to death, but based on the amnesty, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

When the verdict was handed down, the courtroom was full of women, most of them elderly and dressed in black. No one spoke, a deep silence reigned in the hall. It was understood that they were obliged to come and assist in making the decision. Of course, most of those women were mothers or sisters of the Ram during the War, but none had any personal grievances or desire for revenge against us, so the announcement of the decision was heard in the greatest silence.

While emptying the hall on the faces of many unknown women I saw visible signs of regret. My brother, Philip, as he came out of the hall, clenched his fist in encouragement and I returned the smile.

In prison we were taken back to the dungeon, I felt that at that moment all the prisoners were locked in rooms thinking and talking about us: “Two more victims on the altar of the Soviet Malok!”.

This time they made room for us in the dungeons. In the corridor, sitting with a civilian, was Lieutenant Progri, a former quaestor and now prison operative. Hamdia had him in the service. When he saw us go down the stairs, he asked us:

-Was he sentenced to death?

-Yes – Hamdia replied.

-There is Allah – was his reply with a pitying tone. Maybe at that moment, he thought he would be with us too, if he had not been a wrestler at the last moment. The sinking boat is abandoned by thousands, not by people.

We went through the door to the right of the stairs and entered an alcove where two doors opened. There were two alcoves, one next to the wall of the captor’s room, the other on the side of the prison yard. These two alcoves had a common electric lamp mounted on the wall. There we found Xhelal Ndreu, from Slova e Dibra, (Cen Elez’s eldest son), Zija Çausholli, from Shkodra, and Nikola Epifanoviç, a Russian who fled the Revolution, it seems to me a former officer who had been a bartender at the Tennis Club in Tirana during the time of Zog. All three were at the window, so we both lay down near the door. I from the right, and Hamdi from the left. My feet met those of Nikolla, and Hamdi’s those of Xhelal.

It was the end of May and the heat was felt a lot from the small window. In 24 hours, we only had a pitcher of two liters of water to drink and leave. For us this was not a difficulty, but something else inside us. We did not lack appetite and sleep. I began to prepare myself spiritually. Life was looking at me like a movie tape, suddenly snapping! I did not feel sorry for the world I was allowing, because I thought I knew him completely and I was not attracted to anything new about him. I was 38 years old, and it seemed to me that I still had to give to the world. I was returning the task to my birthplace with life.

During my 13 years of student life, which I had spent abroad and abroad, I always had the desire to return home. Though I thought it was not a life paved with flowers. In the midst of a poor, afflicted, uneducated people, only the desire to know could give meaning to life and nothing more. Without too much fantasy neither for the people nor for themselves.

I spent 12 years of my active life thinking through our minds, I felt my conscience completely calm, and the very process that the communists did to me was proof.

Nikola Epifanovici, told me that exactly in my place was Hidajet Kulla, whom I had known in Korça, when he was Qark – Gendarmerie Commander. From there, Nikola told me, they had taken him two months ago to execute him. He was much older than I was, and before he left, he had asked the captain to go to the toilet. They had not even allowed him to be ridiculed. But he had greeted his comrades manfully, had gone without answering the guards.

The other friends silently listened to Nikola’s story. I clearly understood that everyone thought our salvation was hopeless. I too thought they were judging right. From the cell that was next to us, voices started coming. Nikola replied to give us our names. He told us that Qemal Karagjozi, Shate Dulla, and two others were there. Qemali asked me about my brother Filip, whom he had known when he was at the National Bank.

Shaten was told that he had been interned in Italy and when fascism had fallen, the allies had released him and thrown him in Albania to fight in the ranks of the partisans. When the war ended, he was imprisoned as an American agent. In the cell of Karagjoz, only this one, food came to him, while to us came the fifth. We often overcooked our food and passed it to them under the electric light. Because others were afraid, while the rest of us had nothing to worry about. Hamdia leaned against the wall and I put them on her shoulder and passed the food to them.

A few days later, Zija Çausholli was removed and brought to Gjirokastra or Delvinjot, whose surname was Bimi or Bini. He was a very agile guy who always went to the window to see my family. He corresponded with his family by writing on the handkerchief that brought him food. His children even showed him safe signs that he could see them. For every move in the yard, he would go to the window and inform us. Xhelali, told endless tales like “1001 nights”. Hamdi liked him very much, especially before he went to sleep. He needed a somnifer. Others fell asleep at the first words.

In addition to the lack of water, we started to feel the lack of cigarettes. Why, except for Hamdi, I did not come to others and everyone drank and drank. They gave it to me to keep and distribute. Hamdi and I were assigned to have a larger number of cigarettes. Often when I fell asleep at night, I would see Nikolla, who had a gray eye. I gave him cigarettes over the ration, and we started the conversation. He once told me that they were asking him to testify against Asllan Ypi. Is it enough for him to tell me that I have things that do not exist to the detriment of myself, without damaging others. This thought tortured him and did not let him sleep.

One evening at 8 p.m., the door opened and an officer entered. Everyone stood up as we were in panties and skirts.

-Uh! – i’a bani – Hamdi Isufi and Ejëll Çoba. Did you get the teskere?

-Yes – I answered.

-Your work is over in two or three days.

-“Okay,” I replied.

He was brought by Hamdi and said:

-We will throw you into the ditch.

I was not impressed by his words, for I did not know him, but his appearance made me despise him. But Hamdi was sparking his eyes, so that for a moment, I was afraid he was making a heavy gesture. As soon as he came out, Hamdi exploded:

-Did he say these words to us as a patriot?!

-Why is this I asked? – I asks.

-Shkodran we have shit! – answer me.

-Who is it?

-Isa Agoviku – he answered me.

With this name it did not seem to me that I had any civic connection. A good part of the Muhajireen element, during the years that the Albanian government had good relations with Tito’s Yugoslavia, was very enthusiastic about this situation and hoped for positions and privileges. Be these and to the detriment of the local element Shkodran, who had sheltered them.

One day, while we were having lunch, we heard a truck stop in front of the prison yard gate. We told that agile Gjirokastra man to crawl with pa. He continued to watch for a few minutes and then sat down to eat.

-What was it? we asked.

-Garbage truck – answered us without eating.

That evening, late suddenly the cell door opened. A handsome young officer, wearing a military jacket over his shoulder, a white ironed shirt, and a shining watch, appeared at the door. I knew him, it was Captain Thoma Karamelo (Sinica), who asked me:

-Do you remember that I once came to court in Korça for a change of age?!

-No – I replied – many years have passed.

-You were sentenced to death after I personally looked at your file. It weighs very heavily. I’m sorry that you are young, that this other one is for Hamdina, but he is old.

You were four and you remained two. When he came out, Hamdi asked me what he meant by that. The only two of us were on trial.

-I am explaining to you – Gjirokastra told us.

-Today at lunch, when I entered the window, it was not the garbage truck, but a truck that took Gjush Deda and Asim Shpuza.

I saw Gjushi telling the Prosecutor, how was this work done?! Asim, on the other hand, looked out of the prison window to say goodbye to a friend.

We knew they were both doomed to death before us. Later, I learned that Gjushi and Asimi were convicted along with Sali Vuçiterni and Musa Gjylbegu. The prosecutor had demanded the death sentence for Gjushi, and for others, life imprisonment. The next day, the president of the court had read a communiqué of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which mentioned the names of all the detainees, and for Asim, he said that he had been captured. The Prosecutor then changed the claim and demanded the death sentence for Asim as well. Thus, both were executed. I was expected to be executed in the dark or in the dark. Now I was waiting for the fatal hour at lunch.

I was very sorry for both of them, as I knew they were innocent. I thought that Gjush Deda was damaged by the short time he had served as the director of the Party. He himself insisted on resigning and his resignation was accepted. His family had the largest number of victims in the entire city of Shkodra. Brothers Kel and Pjetër Deda, cousin Kolec Deda, brothers Dom Nikoll Deda and Gjushi, nephew of Kel and Pjetr, Simon Darragjati, were imprisoned, imprisoned by his brother Lin Deda, nephew of Kolec, Guljelm Deda, nephew of their sister Zef Trifoni and his wife Mary, who was killed along with Peter in the cave. I was told that Marie was buried where she was killed and is called Marie’s grave. She was the daughter of Shtjefën Zojzi, much younger than her husband.

It is said that in 1945, when they wanted to escape, she told her husband that at no time should she fall alive into the hands of the communists. When the security forces surrounded them, they had no chance of escape, and Peter, after killing his wife, killed himself. This is well known to their apprentice, who joined them. He spent several years in prison and was released. This was the subject of a modern tragedy.

How many events have happened in this brave and fortunate Albania of ours! Thus, the days passed and I felt that he would separate me from life or from death, he was approaching. Every arrival of the truck at the prison gate or every movement of the guards alerted us. This happened on June 17, 1947, when after we had eaten bread, the door of the cell was quickly opened, and the execution captain appeared, along with three guards who were standing seriously behind him. In a commanding voice, after glancing at us, he said:

-Çngjëll Çoba and Hamdi Isufi, get up, because it has been so for you!

We got up immediately and started getting dressed in a hurry. He said:

-Even these clothes that you are wearing, we will take them away from you there.

These words brought to mind the appearance of the jackal, but I did not give up. After I got dressed and was going down to the cement, the captain told us, ask your friends for the halal. Then I saw the three of them, who had frozen like stone statues and were looking at the ceiling. The eyelashes did not play. They seemed so worthy of men that I did not say a single halal word to them.

I headed first through the door where the captain had taken his place, followed by Hamdi. The captain did not play from the spot, and I waited for him to open the door for me. Then the smiling face of a man with a eunuch voice said to me:

-How are you?

This was the Director of the Prison, a Korçar. After I told him the name, he told me that: power spares life.

-Thanks – I replied in a perfectly normal tone. So much so that I was surprised and did not get excited by this news.

When he asked Hamdi about his name, he told him that the government had spared his life. The director paused for a few seconds. I had the impression that they were separating us, and I was not leaving my friend alone in the most difficult moment. The director slowly read that: the government spared your life too.

Immediately the captain extended his hand to us, followed by the guards and then the director. I shook their hand, without the slightest pleasure. My contempt for those people who had hoped for me without comedy in that tragic moment began to boil. I had been a judge for 10 years, and with the greatest pleasure, I had pronounced acquittals or light sentences. And when my duty required me to read heavy sentences, I would say with the utmost seriousness: “May God overturn this decision.” And I sincerely wished I was wrong. Memorie.al