By Sokrat Shyti

Part Four

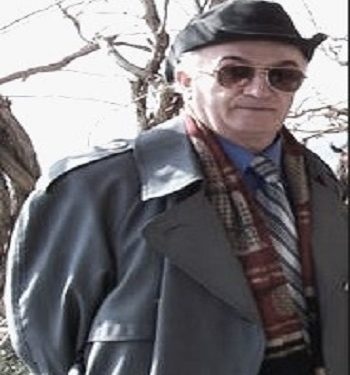

Memorie.al / The writer Sokrat Shyti is the “great unknown” who, for several years, has revealed the tip of the iceberg of his literary creativity. I say this based on the limited number of his published books in recent years, particularly the voluminous novel “Nata fantazmë” (Tirana 2014). The novels: “BEYOND MYSTERY,” “BETWEEN TEMPTATION AND WHIRLPOOL,” “DIGGINGS OF NIGHTMARE,” “THE SHADOW OF SHAME AND DEATH,” “COLONEL KRYEDHJAK,” “THE WITHERED HOPES,” “THE TWISTS OF FATE” I, II, “SURVIVAL IN THE COWSHED,” as well as other works, all novels ranging from 350 to 550 pages, are in manuscript form waiting to be published. The dreams and initial enthusiasm of the young novelist, who returned full of energy and love for art and literature from studies abroad, were cut short early by the harsh edge of the communist dictatorship.

Who is Sokrat Shyti?

Returning from studies at the State University of Moscow, just after the interruption of Albanian-Soviet relations in 1960, Sokrat Shyti worked at Radio “Diapazon” (which at that time was located on Kavaja Street), in a newsroom with his journalist friends – Vangjel Lezho and Fadil Kokomani – both of whom were later arrested and subsequently executed by the communist regime. In addition to the radio, the 21-year-old Sokrat, if we imagine him, had passionate literary interests at that time. He wrote his first novel “Madam Doktoresha” and was on the verge of publication, but… alas! Shortly after the arrest of his friends, as if to fill the cup, a brother of his, a painter, fled abroad.

Sokrat was arrested in September 1963, and in November of that year, he was family-interned (with his mother and younger sister) in a place between Ardenica and Kolonje of Lushnja. For 27 consecutive years, the family lived in a cowshed made of reeds, with no windows, while Sokrat was subjected to forced labor. During these 27 years, he was legally obligated to report three times a day to the local authority. He had no right to move from the place of internment, was deprived of any kind of documentation, etc. In these conditions, among a cowshed, he gave birth to and raised children. Precisely from this experience, or rather a very long story of persecution, he was inspired to write the book “Survival in the Cow Shed”!

Agron Tufa

Continues from the previous issue

EXCERPT FROM THE BOOK, “SURVIVAL IN THE COWSHED”

“Therefore, to avoid any misunderstanding as to why we are not staying a few minutes longer, please explain to the boss that the caretaker is escorting the ‘professor’ to the travelers’ agency. Thank you again for the hospitality! The coffee with cream and the pastries were wonderful!” – he added, getting up after glancing at his watch.

“We feel honored to serve such esteemed clients!” – said the waiter, accompanying us to the exit.

“The pleasure is mutual,” – the caretaker emphasized.

“Shouldn’t we hurry to arrive on time?” – I asked, worried.

“In five minutes, we will arrive,” – said the caretaker, quickening his pace.

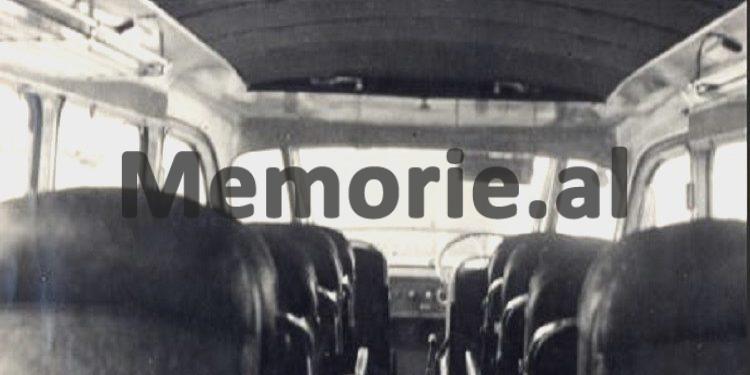

The conversation in the ‘Big Café’ with the caretaker of the dormitory, and the hospitality from the local manager and the staff, brought a temporary improvement to my heavy emotional state. We arrived on time: the travelers had taken their seats, while their companions watched from outside, through the thick glass of the windows. At the door, the manager was talking to the bus driver, looking at his watch. They had checked the tickets and were discussing the two available seats, how minutes before departure, the right to authorization was maintained, and when this deadline expired.

“According to the internal regulations, authorized tickets differ from emergency reservations,” – the manager explained.

“Where does the difference lie?” – asked the driver.

“Only individuals from state institutions are provided with authorization, while in emergencies, those with urgent needs are included, regardless of whether they are citizens or villagers,” – the manager added.

“When such cases do not appear at the agency, in order not to disrupt the departure schedule, up to two seats are left at the driver’s disposal for use during the trip. Finally, you arrived?!…” – he added, worried when he saw me with the caretaker.

“I calculated it down to the seconds that we would arrive just in time before departure, because I know that the manager has a strict watch, and he does not allow any violations,” – the caretaker humorously replied, and went up to put the suitcase away so it wouldn’t block me.

-“Now you can leave,” – said the manager to the driver.

-“And you must keep an eye on the young man!” The bus engine roared loudly, black smoke billowed from the exhaust pipe, and it started moving. Compared to the back seats, especially the two rows facing each other (where one sits frozen, enough to numb the knees!), my seat number five belonged to the privileged ones because it had a clear view and a certain breathing space that wasn’t suffocating. I noticed that at the Drin Bridge, the checkpoint’s beam sat low.

-“Get the Notifications ready, standard check,” – announced the driver to the passengers, opening the door for the captain. I glanced at the metal bridge. The whirlpools of water were clearly visible. The river had not yet fully tamed its spring ferocity: only a palm’s width separated its turbulent surface from the lower part of the bridge’s floor. The floods this year had been horrific: many houses were flattened, hundreds of livestock drowned, and thousands of acres of crops were swallowed! Fields still appeared covered in water, and there was a roof that had survived the crazed fury of the powerful currents.

-“It’s very rare for the Drin to behave towards people like a normal river,” – said the driver when the captain got out of the bus after the check. The gloomy view of the flooding reminded me of an adventure from last year, when we, several high school boarders, came here expressly to admire the majestic Buna, standing on its bridge. At the end of the school year, when the final exams were approaching, we took advantage of the Saturday outing freedom to see the entrance of the city, a truly unusual and magnificent view, encircled by two rivers and the largest lake in the Balkans.

But especially, we were drawn to the Buna, with its width and fantastic tranquility, the only navigable river. We were curious to see how the waters of the Drin poured into its bed and how this connected with the enormous space of the lake that bears the name of the city. After we finished observing in all directions, we directed our gaze from the heights of Tarabosh to the Rozafa Castle, turning our curiosity back to the placid flow of the Buna, below the bridge. Here we caught sight of something special that sent shivers down our spines and lured us with an extraordinary adventure: a few daredevil thrill-seekers leaped from the height between its two legs directly into its depths, and when they surfaced, they swam straight to the shore!

-“Who among you knows how to swim and is sure they can handle the jump from this height?” – asked one of us, directing the question at me.

-“Let’s not rush to answer,” I replied. “First, let’s get closer to them so we can see better. I can swim back and forth across the width of the Buna without straining. As for the jump, I need to think and make a comparison…”

-“Are you going to compare yourself to someone else, or are you going to compare places?” – asked one of my friends.

-“When I was a pioneer at the camp in Vlorë, we secretly went to ‘Doctor’s Rock’ just to jump from this height. If I managed it there, why shouldn’t I manage it here?!”

-“Well, the river and the sea are two completely different things. Besides, here are the legs of the bridge…” – added the friend who asked me the question. “What if you crash against the underwater concrete block?” – “Your observation stands. Let’s ask this young man who has jumped twice…” – I said when I saw him coming toward us.

-“I understand why you hesitate. I had the same fear at first: I was scared precisely of the invisible underwater part. But now I have the spot fixed in my mind, and I jump without feeling the danger,” – he replied proudly.

However, our general thought was not to involve ourselves in such a dangerous adventure, considering that some passerby might recognize us as boarders and report us to the director. But we did not give up on bathing in the river. The next day, Sunday, around 10 o’clock, when the sun was high and the warmth began, we headed toward the Middle Bridge of the Kir River, passing through the peripheral neighborhoods to avoid being noticed. After about 45 minutes, we arrived at the site near the Middle Bridge. It was a clean sandy area, with no grains of sand at all. But the inviting allure was caused by the crystal-clear water, transparent down to the depths. Although it was still early, and the water had not yet reached the right warmth, we couldn’t resist, took off our clothes, and with only our underwear on, we waded in.

As the chill from the unsuitable temperature sent shivers through our bodies, we emerged and began to jump and run back and forth until we warmed up. Thinking that the water would warm up after 12, we decided to make the most of our time by repeating some questions. We lay back on the grass with our backs, placing our removed clothes beneath our heads as cushions. With our skin wet, we absorbed the sun’s rays more quickly, which helped us focus our attention on reading. After half an hour, we started clarifying the more difficult parts out loud. Then, once the clarifications were done, we would dip back into the crystal-clear water to refresh ourselves. To protect us from surprise punishment, one of our friends took on the role of lookout.

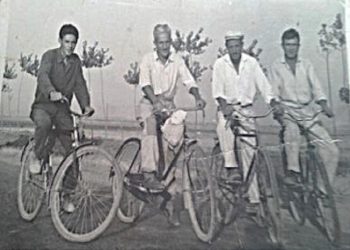

This idea was born from the previous day, after the reluctance to swim across the wide Buna, and it was decided that the next day we would go to the Middle Bridge over the Kir to sunbathe and swim, as long as we kept the situation under control, even though it was rare for any passerby to appear there. To be honest, none of us in the group thought that among us could be a spy who would signal caretaker Tish in the evening about the next day’s action, the group going to the Middle Bridge expressly to bathe, and he would head towards us on his bicycle around 11!

Fortunately, the signal was given at the right time when the caretaker was about a kilometer away, allowing us to hide without leaving any traces of suspicion. The credit for not being discovered belonged to the sharp-eyed lookout, as well as the surroundings which, thanks to the dense brush, made the area look completely deserted, without any signs that just moments ago, a few first-year boarding school students were basking in the sun!

The caretaker left extremely annoyed, feeling that his effort was in vain. He was irritated that he had fallen victim to a claim without delving deeper, thinking it might have been a hasty, frivolous fabrication, and he was immediately ready to take action, believing it without processing his testimony, when he could have conducted the surveillance differently by sending one of his constant spies among the boarding school students? However, despite not noticing a single human breath in the desolate environment, he couldn’t shake the belief that we were hiding somewhere.

But in that moment, a frightening thought plagued him: “What if someone takes a photograph of me from some unseen corner, and when the four years of school are over, specifically after the state exams are given and the Diploma is obtained, they show it to me face-to-face, telling me that with the actions of that day, I will remain in their memory as a negative character?!”

Therefore, it seemed best to return to the dorm, with his tail between his legs. He would pretend that nothing had happened. Even when he saw the spy in front of him, he would act completely dismissive and communicate to him through silence: “You are scum and you will remain such for your entire life!” The outpouring of this resentment was enough to make him give up on punishing the deceitful one who mocked him openly, but he would never forget the deception, keeping it in mind.

After the caretaker left, once we were sure he wasn’t returning a second time to catch us in the trap, we set off through the peripheral neighborhoods toward the wonderful park of the Culture House, adjacent to our dormitory, intending to deceive him for the second time, creating the convincing impression that we had been there since breakfast.

The caretaker turned for iron when he heard this report, through one of the most trusted spies, who, to show that in familial friendship with a fellow villager among the high school students, did not come with the support of his guardian, spun this harmless deception. But the doubt that we had played him, mocking him like a circus buffoon, never left his mind for a moment.

He always looked at us with a weasel’s gaze, as if he wanted to say: “Don’t boast, because once the mouse went into the mustache! After all, the pear has its tail behind!” After the summer holidays and the start of the new school year, in the second grade, we noticed that caretaker Fadil was somewhat cold toward us high school boarders. This changed attitude made me think that someone must have whispered in his ear about our behavior at the Buna and Kir Bridges. I felt it was my duty to deny this claim, labeling it as a slanderous fabrication, explaining that neither our family upbringing nor the responsibility of being high school students allowed for such behavior.

“These fabrications,” I added, “are deliberate; they aim to throw dust and mud upon us high school students, to undermine the good name of this school. They have ambitions because after completing four years, we are given many more opportunities for scholarships at higher education institutions, both domestically and abroad. Therefore, to reduce these chances, they hit us in the back from time to time, concocting rogue tales to create moral black spots.”

Caretaker Fadil did not speak but merely gazed at me with his glassy eyes, wanting to determine how much truth there was in what I had said. He too had noticed the overwhelming ambition of the absolute majority of boarders against our small minority, around 20 in total. Therefore, he took pleasure in this and sought for us to earn a change in judgment, to stand with dignity at the forefront of social emancipation, considering the real fact that our small boarder minority was accompanied every day by city boys and girls from Shkodra or those coming from Podgorica and Ulcinj; thus, we generally had the concrete image of civilization.

Meanwhile, at the Pedagogical School, the peasant composition remained unchanged. In fact, he noticed a fundamental difference even within our small group of 20. From this change, he determined the essential differences between high school boarders from the same background, as the gap appeared in every action and during speaking between urban and rural upbringing.

My relationship with caretaker Fadil during the second-year school year became primarily stronger after the month of special evaluation from the school administration and the Pedagogical Council for me, when I was assigned the unusual task for a student (to break down and explain a teaching program before military personnel of adult age). Bridges of new, mutual, friendly connections were established between us so significantly that it saddened us that at the beginning of this school year, there were some ordinary misunderstandings. His assessment of me took on serious dimensions beyond any expectations. He began to express the need to consult with me about difficult mathematical and physics problems.

Of course, I was pleased that he actively participated during study hours, showing himself ready and tireless to help weaker and average students; he felt satisfaction when they grasped his explanations. The deeper I delved into his mental and spiritual world, the more I discovered the significant differences between the characters and cultures of the two caretakers, not only from a social perspective (while Tishi, over forty, was still single, Fadili was a married man, a father with children), but primarily in how they communicated with the boarders. Tishi had his mind on the boarding school girls: his lustful male gaze often exceeded the bounds of an educator’s duty. Especially when dance nights were organized in the large dining hall, his enthusiasm and desire to dance with the big-bodied mountain dwellers were very noticeable; he was even willing to invite them when the cavaliers had the power…!

When I compared the evenings in the dining hall (with the air mixed with the smell of stewed dishes and washing liquids, the rural style of dance, the primitive orchestra, the peasant attire of the boys and girls, the hairstyles of the mountain dwellers, and the dresses sewn in the same model, not fitted to body shapes) to the festive evenings of our class with our wonderful orchestra (Franci on trumpet, Paulini on violin, Mitika on accordion, Xhavidi on drums and guitar—all students of this class!), and in front of us, the boys in short pants, while the girls dressed in every color of the rainbow fluttered like butterflies, light and graceful, like sprites, the difference between night and day did not seem exaggerated at all.

This fortunate abundance made students from other parallel classes look at us with envy; they were frustrated and jealous that our class had gathered the most talented and agile. However, the organizing committee of the festive evenings, which constantly entertained us with humor, was also quite careful with the beautiful girls from other parallel classes, including those from the first grades. Meanwhile, strict restrictions were imposed on the flirtatious boys, except for the musicians who replaced our friends so they could relax and were given the opportunity to dance. Of course, the music repertoire included only allowed dances (tango, waltz, rumba, foxtrot), orchestrated with professional finesse, with four to five instruments. But when Mitika felt the excitement of inspiration, he never missed a chance to sing, an opportunity to please himself and attract the attention of the high school beauties…!Memorie.al

Continuation in the next issue

Copyright©“Memorie.al”

All rights to this material are exclusively and irrevocably owned by “Memorie.al”, in accordance with Law No. 35/2016 “On Author’s Rights and Related Rights”. It is strictly prohibited to copy, publish, distribute, or transfer this material without the authorization of “Memorie.al”; otherwise, any violator will be held liable under Article 179 of Law 35/2016.