By Ahmet Bushati

Part fifty-two

Memorie.al/ After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

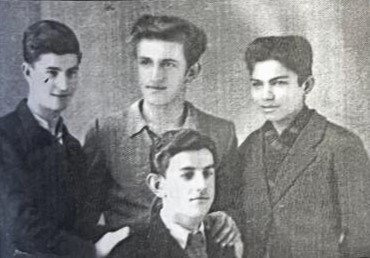

Ismail and Olimbi Baruti, the orphaned children of the respected Colonel Ali Riza Kosova, with whose name the area around the military barracks during Zogu’s time would forever be associated – somewhere without going to the former “Stalin” Textile Combine in Tirana, since the death of their mother, would live in Shkodra with an aunt whose husband was Zogu’s former major Hamza Kuçi, who was imprisoned at the time. Olimbia, one of the most beautiful girls in the gymnasium, had completed two grades of gymnasium before the event we are telling, while Smajli, had just received his high school diploma and had recently been employed in a cadastral office.

As a student, Smajli had participated in the “Albanian Effort” organization, of anti-communist students, while Olimbia would tell how she had once distributed leaflets in the corridors of the gymnasium and, under the doors of the classrooms, leaflets that Sebahet Mulleti had given her, who at that time was excluded from the youth. Speaking of Sebahet Mulleti, Olimbia would say: “She was the best person in the world, the most talented in her studies and the most beautiful in the gymnasium”.

As for the day when Sebahet suddenly died, before she had even turned eighteen, she would say that; “there was a great day of mourning for anyone who had known Sebahet”. There is also a story connected with the name of Ismail Baruti and his sister Olimbi, a typically arduous, painful and dangerous adventure, like many Albanians who then and later sought to find freedom denied in their country abroad, this adventure titled by the author of the book; “The Odyssey” and “The Tragic End” of the group called “Ora e Maleve”, which briefly interrupted the continuation of life in prison and camps, we are setting the scene as follows: “The Odyssey” and “The Tragic End” of the group called “Ora e Maleve”

One evening, sometime after mid-September 1949, Ismaili would surprise his sister when, with unusual seriousness, he would address her with the words: “Olimbi, shall we die together”? Meanwhile, Olimbia, not understanding any of her brother’s frightening words, was completely stunned and turned sadly towards him, who with a fixed gaze awaited a clear answer, would say two or three times: “What are these words, my brother?” and would only be relieved of their anxiety when Smajli continued even more seriously: “I want to escape, Olimbia, but not without you.” For such a purpose, they would contact Asim Rus, the younger brother of Hajdar Rus, who had been imprisoned for three years. In connection with the above, one afternoon, the brother and sister would head to Asim’s house, who, knowing the time of their arrival, had come out to wait for them in front of the courtyard door, on the side of the road, and who, in the back, in order not to arouse the attention of any neighbor who lived downstairs in his house at that time, had thought of crossing the courtyard once with Ismail and a second time with Olimbina.

And it would happen that when Asim, after having brought Smajli into the house, turned to the door to take Olimbina as well, and precisely at the moment when he was about to cross the threshold of the large courtyard door, the Sigurimi officer, Shaban Saiti, would suddenly appear, with a revolver in his hand, approaching Asim and saying: “You are under arrest.” Asim, having happened to be dressed in pajamas, would ask him to let him put on clothes, which he, after a short hesitation, would accept. Asim in front and Shabani behind, with the barrel of the revolver resting on his back, they would cross the courtyard of the house, and while they were passing the top of the stairs, Ismail, suddenly emerging from behind a room door, where he had been hiding, would throw himself on Shabani’s body and together with Asim, in the ensuing struggle, they were able to take Shabani’s weapon and roll him down the stairs.

While Shabani had hurried to Dega, to rearm and take his friends with him, Asimi, Smajli and Olimbia, without wasting time, had set off for a house on a street with a bad name, later renamed; “Carnation Street”. Since, out of fear, the owner of the house had not accepted them, they had changed direction and set off for the house of their friend, Xhelë Oroshi, in the “Dudas” neighborhood, the son of the brave Nuh Oroshi, who had died three years earlier from torture in detention. In this house, they would not only be welcomed without any hesitation, but also with the warmth that is usually reserved for her loved ones.

Olimbia, speaking of the people of that house, would not know how to find the best words for them, especially for Xhyhere, the widow of Nuh Oroshi, whom she would call; sometimes “noble” and “generous”, for the behavior and great care she had shown for them, and other times he would call her “man” and “sokole”, for the courage she had shown in protecting them until the end.

At the end of about twenty days, they dressed as women, with black sheets and Ismaili with a tray on his head, one day they would leave the hay tower of Oroshej, where they had been hiding until then, heading to the “Ndocej” neighborhood, to the house of a Kosovar and loyal friend of their father, named Evzi Gjollapi, known in Shkodra as Hysni – a former army cook once in the Ali Rizaj barracks – where they would stay until he provided them with the opportunity to escape.

At first, he would connect them with a certain Marash Leci, who lived somewhere deep in the street behind the Great Church, where they would spend only one night and, the next day, led by the brave and loyal, Dede Pjeter Volaj, with Shaban Sait’s former revolver at his belt, they would be taken to their other friend, Qerim Muka, in Postrribe, who would also give them an automatic rifle. When they entered the area of Ura e Shtrejte, Deda would return to the village to secure a piece of bread, and on that occasion he would encounter an ambush consisting of two policemen and a non-commissioned officer, who, suspicious of him, would ask him where he came from and where he was going, and finally would seek to arrest him, which they were unable to accomplish, because Deda, agile and courageous, had managed to slip out of their hands, opening fire on them and wounding the non-commissioned officer on that occasion.

Their journey, constantly hidden by the darkness of the night and the distance from the villages, would be very long and arduous. They had to go through winter on the mountains and hills with great cold and continuous snow. During the day they would wander through frozen caves and abandoned stables, and only once would they find themselves inside a warm goat pen, where there would be plenty of chestnuts and, even, sheepskin coats, but more than anything, there would be lice, to which they would immediately fall prey. But Deda, with experience, would tell them that as soon as they went outside, those lice, in contact with the cold, would immediately die, as indeed had happened to them.

No matter the route, only Deda knew, and he himself would be the one who would keep the group’s spirits alive, sometimes with a piece of bread and sometimes with chestnuts, which he would provide them from time to time. The great hardships they were enduring and the roads that were not yet finished had led them to call their adventure once “The Mountain Road” and, another time; “The Mountain Hour”, when they had taken into account that something beyond their logic had taken them under protection and saved them from dangers.

On one of the last days of December, Asim Rusi, suddenly, would fall unconscious on the snow, along with the automatic rifle that had never left his hands, not even when Smajli had begged him to relieve him of an excessive burden, for his powers were almost completely exhausted. In that case, especially Deda, who was still strong, would give Asim a lot of massages, but to no avail, because Asim, from the beginning, had closed his eyes forever. And he had only had twenty-four years to live! Deda and Smajli, having cleared the snow earlier, were able to dig a small grave and place Asim’s automatic rifle next to the lifeless body. In the end, Deda made the sign of the cross, and Smajli said: “Asim, goodbye to that life”!

They would continue without Asim, the last stages of their journey, but if they did not continue to take their chances, fate would have betrayed them: the winding border line had made them believe that they were walking through Albanian land, while in fact they had already entered Yugoslav land, and they would have believed that they had finally crossed into Yugoslav land, when they had mistakenly re-entered Albanian land, just as the appearance of the Albanian post, having taken it for Yugoslav, they would have greeted it with joy and waving two white handkerchiefs that they had brought with them.

They would have been amazed and disappointed beyond measure when an ordinary Albanian captain appeared before them with an automatic rifle in his hand, when they finally understood the trap they had fallen into with their own feet. To the captain’s question; “Where do you come from”? – they had answered immediately: – “From Gjakova”. – “What, from Gjakova”? – the captain had continued. – “Are you all torn and exhausted? Gjakova is not far”, – the captain had concluded once and for all, while Smajli and Olimbina had started to speak among themselves the little Turkish they knew, as if they belonged to the Turkish minority that had been there in Gjakova.

“What are your names?” the captain had continued to ask them. – “Hasan Neziri”, – Smajli had spoken for himself, and after him Olimbia; “Nafije Neziri”, Nezi, while Deda, avoiding answering for the captain, continued to ask for the umpteenth time to ask their permission to jump on the captain, which they, due to the fact that they could barely stand, did not approve of.

The post office staff initially believed their alibi, and since their legs were very swollen, they would also hospitalize them. During this time, Deda begged Smajli several times to let them escape together, but Smajli, thinking about his sister, did not accept, and he did not accept even when Olimbia herself had told him several times in a row; “Smajli, go with Deda and escape, because nothing escapes me from prison”!

Finally, Deda was the only one escaping, having passed by Asim’s grave, which he had opened and closed, after having taken out his automatic rifle from there, he finally crossed the border without difficulty, while Smajli and Olimbia’s hands were handcuffed. For all of the above, the Sigurimi in Shkodër had been informed and their envoy, Ragip Hoxha, upon arriving in Tropoja, would address Smajli and Olimpija, asking them ironically: “Who is Hasani and who is Nafija?” and after their prides had been crushed for life, Olimpija would kick them and even call them a bitch, even though she was only a girl, eighteen years old!

After a few days, they would set off on foot for Kukës, with a horse-riding captain in front, whose name was Mujo (Mujeci), and two policemen behind. After a few hours of travel, Mujo Mujeci, together with them and the two policemen, would return to his house and, having stopped somewhere not far from the road, where they would rest and eat something.

In our small country, no coincidence should be taken as great, or even as strange, so when the father of Captain Mujec, indifferently asked the two arrested, about their names and whose children they were, after in response receiving the names Smajl and Olimbi and, that they were children of Ali Riza, he would immediately rise as if by a spring from his seat and, very surprised and full of longing, would bring his face close to Smajl’s, saying to him: “Yes, a Tuku, is that you?” – and hug him with tears on his cheek.

Old Mujec, had once been a member of Colonel Ali Riza’s closest ward and, on that occasion, had acted, so to speak, as a member of his household, and among other things, had not forgotten how the people of the house, in affection, had called Smajli; “Tuku”. Overwhelmed by memories of Ali Riza, and even more by the pain for his two imprisoned children, he begged his son to escape with them to Yugoslavia, which according to Muje himself, he had no way of doing, either due to the presence of the two policemen he had with him, as well as the devastated physical condition of Smajli and Olimpija.

One day they would arrive in Shkoder, where the deputy head of the Internal Affairs Branch himself, Irakli Kocani, was waiting for them for questioning, who would later, as an investigator, treat them very harshly. For a month and a half, Olimbia had as her prison companion a certain Marije Tucit from Mirdite, who had been as devout as a nun, as courageous in her connections with the escapees, and who would eventually die after a few days in prison, from peritonitis.

The brother and sister would one day appear in court, along with some students – who with Smajli had been part of the “Albanian Effort” group – in which case Smajli would initially sentence them to death and later have their sentences commuted to life, to ultimately serve eighteen years in prison, and Olimbia three. Even the post-ribbi Qerim Muka, who a month earlier had provided them with an automatic rifle, would serve ten years in prison.

We finally leave Shkodra prison

One afternoon around mid-May 1951, we were taken out as usual for the airing hour in the large prison yard, and when we saw that some of the prison staff had letters in their hands, we had no difficulty understanding that it was about going to the camp. And so it happened: the names of all those who were going to the camp were read out, and right there, the shaking of hands and the hugging of prisoners, who were leaving on that occasion and those who were staying there, began.

As in other cases, those who remained, although saved for themselves, openly expressed the sorrow of separation, while those who were to leave, even considering the suffering of the camp, as well as the great difficulties for the families who would return with a thousand hardships, remained restrained and often even encouraging, towards those they were leaving behind in prison.

On that day, movement from one room to another was free, and the prison was bustling with the hurried movements of the prisoners who did not trust time, which, as if behind them, slipped away unnoticed, which prompted them, pair by pair, to climb and descend the two prison stairs without rest, so that, as if they were escaping from life and the world, they would necessarily seek forgiveness from all those with whom they had faced the difficulties of a prison and shared everything together.

I found Nush Simon outside in the corridor, in front of rooms no. 2 and 3, for the sick. “I knew Ahmet, that you would come to see me,” – Nushi told me as soon as he saw me, while I was noticing him more sad than ever. He was completely lost in health and looked down most of the time, he spoke with difficulty, which took his breath away. It was clear that his illness had progressed a lot, perhaps also due to the lack of medication! And who else like Nushi, had been in good health and happy about life!

In the end, I hugged him, wishing him well and that one day we would see each other again, and he, as if to hide his helplessness and general state, and perhaps more strongly the longing he must have felt at that moment, without looking up from below, wished me two or three times: “Have a good journey, Ahmet, may God keep you healthy”!

I parted from Nush Simon, with the longing that I was leaving him counting the last days of his life. The last partings, generally quick and short, were done first with the prisoners of other cells, while with the prisoners of the cell, of which they had been a part until that day, they were left for last and would generally be longer.

One of my best friends, Ali Brahja, whose face constantly reflected a clear conscience, I would see from afar that he was waiting for me at the door of the room, with all the belongings in his hands, ready to give them to me. Even before I was close enough to the door, where he was waiting for me, I called his name, and suddenly he burst into tears. And what tears! He was crying, his hands and body shaking, which moved me too.

Perhaps the idea that we might never see each other again – as it really would – had weakened Ali Braha to that point, which might have suited Ali Braha the “teacher”, but not Ali Braha the spoiled and firstborn, nor Ali Braha the committee, for two years in the mountains, such was the prison bond that it had overturned even some rules that had been considered mandatory norms of behavior! Memorie.al

Continued in the next issue