By Shkëlqim ABAZI

Part forty-one

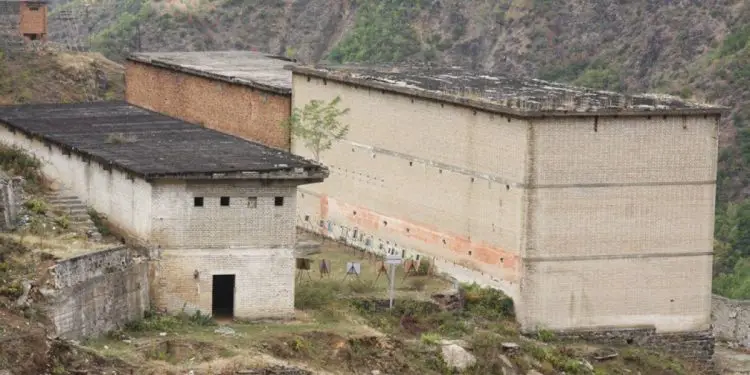

S P A Ç

The Grave of the Living

Tirana, 2018

(My memories and those of others)

Memorie.al /Now in my old age, I feel obliged to tell my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds and of others whose mouths the regime sealed, burying them in nameless pits? In no case do I presume to usurp the monopoly on truth or claim the laurels for an event where I was accidentally present, even though I desperately tried to help my friends, who tactfully and kindly deterred me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you only have two months and a little more left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet, from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months after, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard during those three days; I would not want to take to the grave.

Continued from the previous issue

Xhike’s Carriage (Continued)

Oh God, I was lost in speculation, the scenes with criminals, as I had fixed them from films and books, appeared on the screen of my mind, and I was shaken with terror, nearly screaming, but the feeling of emasculation before the women turned out to be stronger than the fear. Their flushed faces kindled a wave of unknown heroism in me until then.

It seems the masculine instinct took over, and I felt like a man.

“Woe if men falter!” A vein of naive heroism struck me.

“Why are you taking the women? They are not at fault!” – I involuntarily expressed the thoughts bubbling in my brain.

“Well then, you wild brave one, we’ll deal with you!”

Two policemen lifted me into the air in the blink of an eye and plunged me into a compartment to the right of the entrance. “Oh dear, what trouble I asked for!”

As I racked my brain for a solution, Marshal Novruzi confronted me: “Now tell us, what you heard in the queue?”

“Nothing!” – I answered curtly.

“And you others?”

When he addressed my friends, I turned my head and winked at them to signal silence. They must have understood me because they repeated in unison:

“Nothing!”

“How, nothing?”

“Nothing!” – all three of us insisted with one voice.

“Were you in the queue?”

“We were!”

“And you neither heard nor saw anything?”

“We saw!”

“What did you see, you devils?”

“Xhike the carter, when he fought with that man!”

“Who started it first?” – his voice seemed to lower, and the tone took on more human nuances.

“Xhike, Comrade Marshal!” – I replied, slightly emboldened by the manner of treatment. I dared because the Marshal’s son was my classmate and a slight rival in lessons:

“Comrade Marshal, ask your Ilir, we are not troublemakers?” – I mentioned his son, hoping to soften him.

“Well then, scram now, and shush! Did you hear?” – and he kicked each of us in the backside.

“Shush! Did you hear?” – he threatened us with gestures and pushed us out the door.

Stepping over the threshold, I turned my head and cursed that terrifying corner, but took care not to open my lips. A little further on, Xhike was strutting with a glass of raki, his eyes swollen from the punches. As soon as he spotted us, he grinned and coughed two or three times, as if to say:

“Don’t mess with me, I have the whole police force behind me and I’ll put you in jail.” Indeed, the state put itself at the service of that scum. Past the corner of the cinema, where the gypsy’s mocking eye couldn’t detect me, I stopped and spat at the cursed building, without realizing that after a few years, these very walls would become my home.

I couldn’t imagine how a peaceful person, which I considered myself to be, could end up in prison without cause. The horse neighed and arched its tail, urinated and defecated, as if doing it on purpose. The neighing, the urination, and the balls of dung that fell, forming a pile at its hind legs, made me conscious of the place I had left; the foul-smelling steam disgusted me and reminded me of the presence of the carriage-prison. I looked at my friends, and they too were stunned and bewildered.

“Damn you,” – the first one cursed. “May you see yourselves dead, all three of you,” – the second one damned.

“May I never see your color or hear your name,” – I concluded, without specifying whom I addressed: the building, Xhike, the horse, or the carriage-prison. We let off steam and set off to wash the dung off at Zarizani. Perhaps in the river water, we were also washing away the sins of the prison. Since the next day, I escaped the queue, but not the phantom of Xhike and the notorious carriage-prison.

As if sensing the danger, my parents withdrew me from all commitments and entrusted the duty to my older brothers.

The Curse of the Carriage-Prison

Two hours of pressure in the imposing building, the “ride” in the cursed carriage-prison, the defiant spy-like gaze, and the horse’s neighing would leave indelible impressions on my young intellect. Whenever I saw animal offal, I felt nauseous; an inexplicable disgust paralyzed my psychomotor activity, almost giving me a heart attack.

Since then, Zengjeli and Koçi, who were stout men, terrified me. When I crossed paths with Xhike or his carriage-prison, I changed direction. When I couldn’t, I lowered my head, closed my eyes, covered my nose, and held my breath until the cursed trio passed; “Xhike-carriage-horse.”

I don’t know why I became fixated on the idea that he deliberately came out and waited to swallow me into the darkness of the rattletrap, amid the foul smell of dung, suffocating me. I became disgusted with all carriages. When I heard the clip-clop of a horse, accompanied by the scratching of wheels on the cobblestones, my hair stood on end, and a virtual flame that came from I don’t know what source of heat, embedded in my sick memory, scorched my skin. The carriage-prison, with the clatter of its wheels, knocked inside my brain, torturing me even in my dreams.

While the whip lashed my mind, the stench of dung caused me allergies, making me willing to take to my heels and flee, to flee and flee beyond the horizon. Since that distant July day, the cursed trio; “Xhike-carriage-horse,” would follow me under the guise of the black cat; perhaps it was my destiny to become the precursor to the auto-prison.

Nevertheless, Xhike with his carriage-prison would remain my nightmare, the weak and most painful point, even after I was repeatedly loaded onto and off the state’s auto-prisons. This cursed trio had set an ambush somewhere in the cells of my brain and attacked the ramparts of my memory from time to time.

In the late seventies, when Mentor Xhemali sang the famous song: “Mora rrugën për Janinë” (I took the road to Ioannina), I felt weak. Although I admired Mentor as a brilliant artist, with his unrepeatable and unique voice, who expressed the character’s sorrows, worries, pains, and joys through his facial expressions.

When he repeated the line:

“…together with the carriage driver, oh, in the night-t-t-t!…,” Xhike and the black carriage-prison appeared to me, darker than the night, and all the carriage drivers who sat on the seats, I identified with the dark, boisterous, thin, tall, somewhat womanizing, somewhat drunk, somewhat conceited, somewhat gossiping, somewhat spying, somewhat ignorant, somewhat cold-hearted Xhike; while the araba where the traveler, whose liver would be shredded, had taken his place, was the carriage-prison that stank of dung, and the swarms of flies made your eyes sting.

And when he dragged out his voice:

“…I was al-o-o-one,” I don’t know how I restrained myself from shouting: “Get off the araba, Mentor, the treacherous Xhike is not taking you to Ioannina, but to the door of Berat prison.”

And when he stopped to give way to the clarinet, which kept the cadence with chords like wailing cries, I sobbed and added, hoping he would hear me:

“Jump off the araba, dear, you’ve ended up ‘a groom in Xhike’s carriage’.” But it was too late, the singer had already begun the second stanza:

“My liver is cut to pieces, and my heart-t-t-t!”, and I screamed under the weight of the nightmare: “Woe to you, your spleen, your tripe, your intestines, all your guts!”

“How were you fooled, Mentor, to confuse Xhike’s carriage-prison with the travelers’ araba, when it’s a carriage of tripe and intestines!?” I was about to burst from the anxiety caused by the brilliant singer’s undeserved pains.

Years after the episode with Xhike’s carriage, I would fall prey to injustice. I, the believer in Themis (Justice), was perhaps born at the wrong time, in the wrong place, and to parents with an unsuitable biography for the communist hierarchs, who, to gain power, promised justice but incited injustice and stoked hatred, sowed wheat and reaped weeds!

This violent clique installed the monster regime, the auto-prison, auto-slave, auto-censor, auto-criticism, auto-biographical system! With these self-denouncing terms, communism genetically condemned whoever it wanted, practiced the destruction of DNA under the maxim: “what is born of the cat hunts for mice,” and gave life Hamletesque dilemmas: “either choose your parents before they conceive you, or bear the consequences of the ancestors’ biography, undesirable to the regime!”

Communist leaders openly declared:

“The enemies of the Party are also enemies of the people and the classes, from whom other enemies are born, and from these, still others, so let us isolate them, destroy them, root them out completely!”

They implanted this slogan in the people and incited hatred, deformed the gene, created homophobia, introduced the apple of suspicion and espionage, overfilled the prisons with thousands of innocents, destroyed the nation’s elite and intellectuals. Whoever inherited the genes of the declassed had to pay the debts of honest parents or grandparents and great-grandparents they never knew.

The fairy tales about “justice” against “injustice” dissolved like salt in water. I, who believed that “Zeus” would unleash lightning bolts on the heads of the schemers, would be bitterly disappointed. I had to complete my training “stroll” in Hades, initially with Xhike’s carriage-prison and a few years later, with the state’s auto-prison, to recognize my naive inexperience and learn what I had never imagined could happen:

Injustice triumphing over right and planting its iron claws on decency and honor, by imposing collective mouth-locking, murderous silence, hypocrisy, and the destruction of the human personality!”

A “Stroll” through the Roads of Hell

The event below pertains to the day I was first loaded into the auto-prison and sent from the cells of Shkodër to the heart of Mirdita. I deliberately left it out of the previous volume because it is connected to the prison vehicle, so I thought to give it a place in this section.

They gathered the few belongings we possessed and tied the six of us, hand-to-hand, with gjermanka (handcuffs/shackles). Besides the handcuffs, the two men at the ends had their free hands tied to a bar fixed to the side rail, and when they were sure they had turned us into a chain of flesh and iron, they locked the door with a bolt and a padlock.

In the total darkness, the isolation cells seemed like flowers!

“Now they plunged us into darkness!” – Someone spoke. But as no one answered him, he repeated:

“Darkness has overwhelmed us, friends!”

In that pit, faceless passengers were panting and breathing. Although we were traveling head-to-head, no one could be distinguished.

“Why don’t you say they plunged us into a grave?” – I spoke aimlessly, not knowing if I was reinforcing the previous speaker or convincing myself. The policemen, who apparently would escort us to the destination, asked us before tying and shoving us into the pit:

“Have you urinated, inside?”

As no one responded, one after the other was addressed:

“Have you urinated, you over there?”

“Yes!”

“And you over there!”

“Yes!”

“And you over there, kid?” – he turned to me.

“Yes!”

“You brought it on yourselves; until you reach the place, your piss will run in streams, you’ll see!”

I didn’t understand whether they were being kind-hearted or if it was their duty.

“Go on, start already!” – said Luigji, who could barely wait.

“You are in the auto-prison, sir; it will shake and rattle you, like a barrel of vinegar!” – and he closed the door. I was pondering when I heard the name “auto-prison”:

Auto! Auto-slave, auto-censor, auto-criticism, auto-biography, auto-grave! Hell, where did this auto-prison come from? As far as I know, “auto” means “self”; self-slave, self-censor, self-criticism, self-biography; agreed; but self-prison doesn’t work! How can you go to prison, or to hell, with your own feet? This is the message!

Although he emphasized “auto-prison,” it seemed meaningless to me.

“Who is that normal person who would self-imprison himself, I beg you?! Perhaps the term ‘auto-grave’ would best suit the darkness where you plunged us?”

I wanted to talk back to the policeman, but I bit my tongue and said:

“In the auto-grave, more accurately!”

“We are going to die here, and God knows where they will bury us!” – added another.

“Well, we will suffer a bit, but we escaped the isolation cells!” – Luigji tried to lift the morale.

The sheet-metal box rattled, and the auto-grave shifted slightly, until the roaring increased, followed by an abrupt braking.

Stop and go, and go and stop, it shook us up properly, let out a puff of smoke from the vent and snorted. “It’s started, men!”

“Where to?”

No one spoke, because you can’t answer a mystery. After a pause, whose duration I don’t know, I recognized Luigji’s voice:

“Anywhere will be better for us!” – he chuckled, delighted to be leaving the cells, where he never had enough. In the darkness of the auto-grave, silence descended.

“The grave sows sadness even when it has wheels!” – I philosophized.

“Ugh, darkness breeds boredom, silence, monotony!” – added Ladi.

“And the grave?” – Someone asked.

“The grave? Of course!” – they replied from the darkness.

“Even when it’s collective?” – I intervened.

“O-ooh, even worse, our bones will be mixed, a terrible disaster!”

Go and go, and go and go, the engine gasped for over an hour, then it fell silent, and the machine stopped.

“Where could we be, men?”

“The devil only knows!”

Inside the grave-prison, total deafness and blindness reigned.

“Take this one too!” – Some faint voices penetrated the sheet metal and pierced the curtain of darkness.

“We have to take him?”

“Who else, hey man!”

“We have no room!”

“Plunge him among the enemies, one less or one more won’t hurt!”

“Is this one an enemy too?”

“No, but they will kill him all the same!”

“We have a long road, friend!”

“Squeeze together a bit and do what you have to do!” – the first one encouraged.

“For the Party’s ideal, we are squeezing hard. Don’t you have any other vehicle, huh?” – Someone complained.

“We are in a year of savings, bless your soul! The Party commands to save everything everywhere, and not to waste fuel on a criminal!”

“Long live the Party!”

“May your mouth sing, hey man of the earth?”

Silence, a humming that was followed by the order:

“Slam him into the Branch and continue further!”

“What if he dies on the way?”

“Oh well, one criminal less!”

After a moment, they opened the door, threw something in, and immediately closed it, quicker than they opened it. Back in darkness.

“Have a good journey, men!” – Someone offered a farewell.

“May you turn Turkish?” – and the grave-prison roared.

Apparently, we were stopping somewhere, dropping off cargo, and continuing further. But where?

The devil only knew! Sharing a ride with crime, something moved near my feet.

“Who are you?”

Silence.

Again, a wriggling of legs.

“Where are you from?”

Silence reigned, so I stopped.

“Must be some lunatic and I got lost in my own worries. But the wriggling increased.

“Who are you, hey man?” – Luigji’s hoarse voice.

“Frani!” – a muffled grunt, almost extinguished, came from the floor.

“Where do we have you from, Frana?” – a northerner. Memorie.al