By Artan Fuga

Part One

Memorie.al / From the history of Albania. Regarding this issue, it is essential to clearly distinguish between two levels of analysis. That is, to distinguish what place and what functions were assigned to the media by propaganda, and what functions they actually performed. It cannot be said in any way that these two levels align with each other, but it also cannot be claimed that they do not share various common points. It is one thing what is said in the press about the media and the entire social life of the country, and quite another the press, the media, and social life represented in themselves.

The concept of the functions of the written press and media in general is often treated as if it remained identical throughout the 45-year period of totalitarian society in Albania. But in fact, in the formulation of the media’s tasks, various and occasional nuances were expressed, which cannot be ignored.

The functions of the media have been expressed, in fact, in two different forms: in the form of general duties and in the form of their concrete duties. The general form includes the functions of the press and media in society regardless of the characteristics of the period. It relates more to the functions of the press and media that are supposed to remain static and permanent. Meanwhile, specific functions express the duties of the press according to the concrete objectives of a given period. These latter tasks may be a priority in one period and may not be raised at all in another.

The functions of the media, as they are expressed, are considered universal – meaning for all types of press, publications, and media. Meanwhile, for every newspaper or magazine, for radio or television, for the Albanian Telegraphic Agency (ATSH), or for the “New Albania” (Shqipëria e Re) Film Studio, specific tasks are also defined. This is how duties within the written press system are defined in an official document of the time – a decision by the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the Labor Party of Albania:

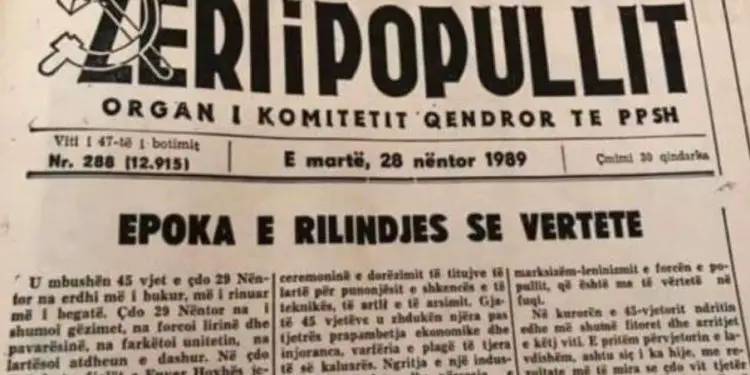

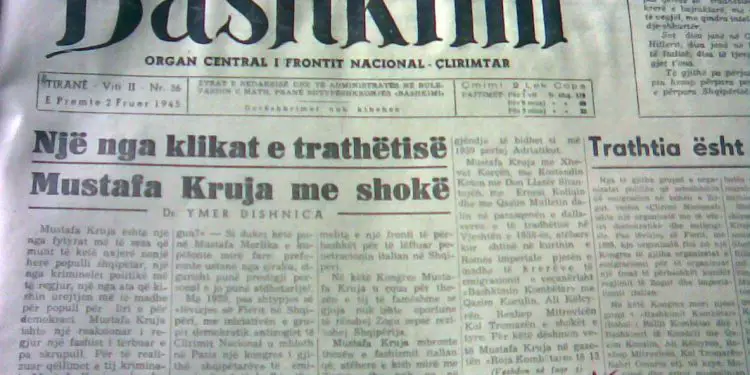

It is emphasized therein: “‘Zëri i Popullit’ is the main press organ in our country that provides the Party line…! The newspaper ‘Bashkimi’ may devote greater care to reflecting the life of state organs, rural problems, as well as problems and activity in the fields of culture, education, and social issues… The newspaper ‘Luftëtari’ must primarily deal with the problems of combat readiness of the army…! The newspaper ‘Puna’ must primarily deal with and reflect the life and problems of the working class…! The newspaper ‘Rinia’ must deal with problems related to the communist education of the youth…!”

After the end of World War II, it does not yet appear that there was a synthetic formulation regarding media functions. The formulations provided are not very precise and do not center around a single axis. Nevertheless, one article, published anonymously and one of the most important of that time regarding the issue in question, is striking. In this article published in the newspaper ‘Bashkimi’, titled “Press and Culture in New Albania,” it is emphasized that the Albanian press of that time should be a “True servant of society and the Albanian people,” and that it “Represents a unity of thought, much like the unique front – the National-Liberation Front – and emerges to protect the interests of this popular unity.”

As can be distinguished without much difficulty, the press and its duties in this period (1944–1948) are defined in function of realizing the “unique” objectives of the Democratic Front. The latter emerges as a union of political and social forces in their implied solidarity. In a way, it is an attempt to think of mass communication policy in a slightly broader way than the aim of placing the press under the direct control of the Communist Party. The tasks of the press in this declaration are considered linked to the commitment to maintain “unity of thought” and to be placed in the “service of the people,” where “the people” is still understood as an amorphous mass, undifferentiated into various classes and social groups.

The part of the population excluded from the term “people” is numerically small. At this time, it is thought that those who collaborated with the occupiers during World War II are outside the concept of “the people.” Later, while political and economic relations with Tito’s Yugoslavs plummeted to very low levels and an accelerated alignment began with the Soviet Union led by Stalin (starting from 1948), the functions of the press were defined differently from before, both in terminology and in journalistic practices.

The press began to be called a “collective agitator and propagandist,” a “collective organizer,” etc. In terms of content, the press was placed at the service of action and social change on class and political bases. It took on a starkly pragmatic and ideological duty. It was no longer linked to the name and duties of the Democratic Front. This organization, in form and content, became nothing more than an obedient instrument of the Communist Party. The subordinations of the press and media were now defined in relation to the Party.

In an article written by Bedri Spahiu – important for understanding the issue we are treating, as it came from an author who at that time held a key post in the party hierarchy as Secretary for Propaganda in the Central Committee – it is emphasized that the press “Will increasingly become a collective organizer and educator of the masses in the hands of the Party and People’s Power.” Only a year had passed, but the definition of the press’s duties was already presented differently. From the Democratic Front, its subordinations passed to the Communist Party.

However, in this year, as we have emphasized, a significant change occurred. Albania had broken away from dependence on Yugoslavia and passed under Stalinist subordination. The model of political society, the state, economic reforms, the model of class struggle, and thus mass communication, had taken on the Soviet appearance. The term “Collective Organizer” itself, attributed as a function of the press and media of the time, comes literally from the Leninist and Stalinist vocabulary.

The above definition remained in force until the early 1960s, while ties with the Soviets began to fade as a result of political and ideological divergences between E. Hoxha and N. Khrushchev, which led to the severance of diplomatic relations between Albania and the Soviet Union and, above all, was accompanied by the expulsion of Soviet military forces from the Albanian military base of Pashaliman. Nevertheless, even in 1962, E. Hoxha still kept the terminology of the waning period in use.

On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the first issue of ‘Zëri i Popullit’, he addressed the journalists working there using the same ideological formulas that had been in use before. He wrote to them: “The Central Committee is convinced that in the future as well, ‘Zëri i Popullit’ will fight as a collective propagandist and organizer for the triumph of the Party line.” Soviet terms for the press, such as “collective organizer,” were still in use. The truth is that this political language did not cease to be used later, but nevertheless, after the break with the Soviets, it began to sound somewhat fainter.

From 1960, the period began when Albania became isolated from other countries of the Communist East, and at the top of the totalitarian political pyramid, the idea of walking on “new paths” was processed. Naturally, within this changed strategy, a new terminology in defining the functions of the press and media had to be developed. After Enver Hoxha’s letter to the fourth Conference of the Union of Journalists of Albania, the definitions he gave there remained as official and the most used. It is understood that the selection of political language was done carefully and with very well-defined political and ideological goals. Of course, even in this case, the term “collective organizer” remained in use, but the new terms used and the idea that “Revolutionary journalists are architects of the revolutionary thought of the masses” took priority.

In this definition, the administrative side of the previous formulation is somewhat softened. We emphasize this because the term “collective organizer” is replaced by the term “architect,” which – intentionally or not – centers the role of the press and media toward more intellectual spheres. On the other hand, terminologically, the media were stripped of a certain practical power, because they were no longer called “organizers.” There is only one organizer – the Party. The period of Lenin’s illegal activity in the Tsarist regime was considered different, where the press, in the absence of state apparatuses, was perhaps the only organizer, as a bureaucratic machine of revolutionary movements.

Likewise, there is talk not of the press in general, but of “revolutionary journalists.” Nor of all journalists. There are revolutionary journalists, but it is implied that there are those who are not. The status of a journalist no longer automatically grants any function or privilege. The threat to journalists – who, if they deviate from the political line in force, could henceforth not be considered on the side of the revolution but as its opponents – remained raised like a sword over their heads.

On the other hand, it is seen that a period began which I would call the self-glorification of the media and the official press. The press did not feel itself like any other “architect” who designs while necessarily keeping in mind what raw material the imagined object will be realized with in practice. The raw material of this “architect,” the journalist, is the people – the masses of citizens. He takes on the ambitious, giantomanic claim of becoming the “architect of the soul of the masses.” To give them the form he desires.

The “revolutionary” journalist is thus seen as a constructive, active factor, while the individual soul of everyone, or the “collective soul of the masses,” is called a passive material that can take those contours given to it by the system of mass information and propaganda. Finally, this comparison with the true architect, the metaphor of the “architect,” entered into use, signaling that, as it appeared in the Albanian press, strategies would be outlined that would lead to significant changes in the coming years.

By the mid-1960s, precisely during the wave of mass movements encouraged by propaganda and integrated into the political strategies of the ruling party, under the influence of the Cultural Revolution in China, the definitions of the press and the role of the media in society underwent further changes. An aspect that was previously overlooked or passed over quickly began to be highlighted. The press and media began to be called in many cases “tribunes” of the thought and aspirations of the broad masses of the population.

This is a period during which the power has an interest in fading the role and mission of the professional journalist, turning him into a simple transmitter of the voice of the “masses.” During these years, the journalist, like the middle or semi-high functionary, undergoes a process of devaluation. It is the time when the power invites the masses to overshadow the role of middle-class cadres – a form of pressure and control over them. Meanwhile, Mao Zedong is leading the “Cultural Revolution” in China under the slogan: “Bombard the Headquarters!”

Enver Hoxha addressed the volunteer correspondents of the media and press of the village of Fier-Shegan in this way: “Without you, both the press and the radio would stall, as you provide them with the primary, healthy nourishment, without hollow stereotypical phrases; you give them the vivid life, the great experience of the people.” It is seen that in this address, the colors of the time are very visibly placed. The dictator exalts the volunteer correspondents of the press and media. He does not address professional journalists.

The latter have reason to see them as devalued. The pressure on them has increased. Furthermore, he does not address all the volunteer correspondents of the country, but simply those working in a village. This is done with very concrete terms. Above all, it is declared that volunteer journalists are those who give life and vitality to the press and media. What remains for professional journalists to do? The shadow of unexpressed criticism looms directly: “You are nothing but press bureaucrats, rotting in editorial offices!”

Nevertheless, it must be admitted that in the political discourse of the time, the ideological balance reached certain equilibrium. On one side, the professional journalist, the “architect” who outlines the soul of the masses, and on the other side, the masses themselves, embodied in the volunteer correspondents who “give life and vitality to the press and media!” A power rivalry expressing a tension, a conflict within those who exercise the profession of journalism.

However, even this last definition would not be long-lived. Through the 1970s and beyond – which represent another period of even more pronounced closure for Albania as it began to separate even from China – a time of even more significant power concentration than before occurred within an ever-totalitarian ideology. The metaphors for the journalist as an “architect” (imagined as a person in a free, individual profession) and for the media as a “tribune” (where ordinary people speak without order) lost their previous force in ideological use.

The media were now considered, more strongly than ever, as instruments of the political action of the ruling party. The “architect” now is the Party; the tribune has been dismantled, and the people, once standing atop it, have been brought down to a rally square where directives are sent to them and slogans are thrown at them from a tribune they are forbidden to climb. The leaders of the media sectors were now forced to speak differently. Quite differently. Pipi Mitrojorgji, one of them, emphasizes in the magazine dealing with media problems: “All our propaganda in the press should serve to mobilize the masses for the successful realization of all the tasks set by the Party for all sectors of our life.”

Meanwhile, in the mid-1980s, the period after Enver Hoxha’s death, as the power sought again to undertake some reforms – legitimizing them based on the dissatisfaction of the masses – efforts were made to reintroduce the idea of a tribune for the media and press. The media were considered a kind of “empty channel,” a sort of microphone extended to the popular masses so they could speak. Foto Çami, who was also the Secretary of the Central Committee of the Party for ideology, culture, and propaganda, wrote that the press and radio-television is a “Tribune of the free democratic thought of the masses and of revolutionary action. Only as such are they called ‘active helpers’ of the Party.”

If we wished to highlight a preliminary conclusion, it would be that within the prevailing ideology, the media were summoned according to the needs of the day with different epithets; their role was named according to various definitions.

There are three main ones:

- “Collective organizers of the masses”: When the emphasis is on their role as instruments for conveying directives, orders, and slogans from the peak of power to the popular masses.

- “Architects of collective thought”: When preparations are made for the media to be used to reform and adapt daily policy according to the political interests of the time.

- “Tribunes of popular thought”: When the power needs to lower the role of journalists, to keep them under the pressure of volunteer correspondents, and by manipulating crowds and inciting them against the political elites who possess power or exercise it from the center to the base.

From all these names, it is understood that the press and media in general are seen as connecting elements between power and the masses. Or they constitute the instrument used by power to achieve this strategic goal as much as possible. How efficient the media manage to be is another matter. This depends on the conditions and circumstances of the time, the psychological state of the masses, the temporary interests of certain social groups, the context of international geopolitics, etc.

Through the media, outside the shell of the ideological speech of the time, the power aims to ideologize their consciousness – to perform what is called manipulation through propaganda. It aims for the broadest and most stable integration possible to direct them toward a given political goal. The messages sent toward the audience can have diverse content. The type of media used or the genre of journalistic practices does not matter.

The message could be a call to move faster in a wheat harvesting campaign. It could be a reportage drawing attention to the life and efforts of shepherds in the mountains. It could be an informative piece on, say, the economic crisis in the Soviet Union while it begins to be called a revisionist country. Or anything else.

Meanwhile, the media play a double role, which is in fact the same as the first. The “masses” are also invited to transmit their messages toward the peak of power: initiatives to increase labor productivity, moral support for the power and the Communist Party in force, news about increasing work intensity – everything required by power that finds, realistically or illusorily, support from below.

Again, the same monologue. It is important that in the press the “masses” transmit through the media that information, those messages, that support the power. Revolts are censored. Dissatisfactions are censored. Collective despair is censored. The expression of personal interest is censored. Shortages of goods in the market are censored. Crime is censored. Life in prisons and concentration camps is censored. Information on political freedoms in the West is censored. The media returns to power that information which power wants to hear, to capture from the day’s current events. Everything else turns into non-existence./Memorie.al

(Original title: ‘Functions of the media in totalitarian society’ – From the history of Albania)

To be continued in the next issue