Part Fourteen

Excerpts from the book: ‘ALIZOT EMIRI – The Man, a Library of Noble Wit’

A FEW WORDS AS AN INTRODUCTION

Memorie.al / Whenever we, Alizot’s children, shared “Zote’s” (Alizot’s) stories in joyful social settings, we were often asked: “Have you written them down? No? What a shame, they will be lost… Who should do it?” And we felt increasingly guilty. If it had to be done, we were the ones to do it. But could we write it? “Not everyone who knows how to read and write can write books,” Zote used to say whenever he flipped through poorly written books. While discussing this “obligation” – the Book – among ourselves, we naturally felt our inadequacy. It wasn’t a task for us! By Zote’s “yardstick,” we felt incapable of writing this book.

Continued from the previous issue...

PART TWO

Mood

SCHOOL, EDUCATION & CULTURE

WHAT IS SCHOOL?

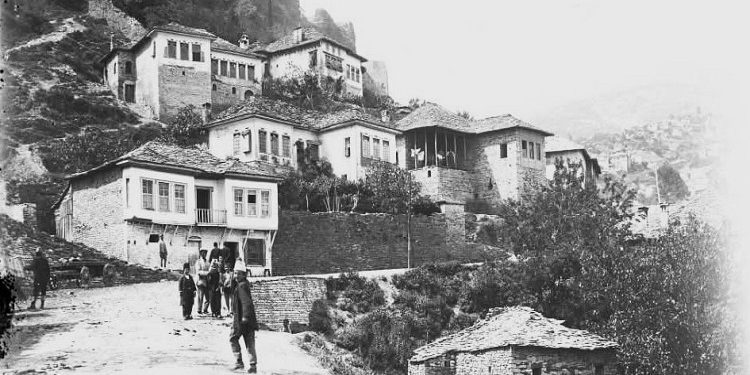

Discussions about school often opened up in the bookstore. Education was a general preoccupation in Gjirokastra. Schooling was seen as the only path to securing an optimal life with dignity. People discussed children’s progress; the names of outstanding students were mentioned with respect by the elders, especially when they were very poor.

“Good for them, bravo! They barely had enough to eat, yet they succeed…!” Their names were well known. But cases of broken discipline were also mentioned, viewed as events that lowered the city’s values. God forbid someone “crossed the line.” The whole city would be concerned! Sometimes, parents weary from a hard life felt powerless against their children’s poor results.

“Come on, don’t worry, the school will ‘bake’ him like everyone else!” bystanders would console the worried parent.

“Listen, what do you think school is?” Zote interrupted one day. “Don’t blame it for nothing! School is exactly like an oven; it bakes what you put into it. Let’s say, if you put in a byrek, it brings out a baked byrek. If you put in shapkat (cornbread with greens), it brings out baked shapkat. It has never happened – anywhere in the world – that you put a pumpkin in the oven and it brings out roast meat! Every parent knows exactly what ‘goods’ they have sent to school.”

The crowd agreed, though they laughed at his comparison. But Zote hadn’t finished:

“School gives you the flour, but you must bring your own sack! If you go with a sack, it fills a sack. If you go with a small bag, it fills a bag. And if your sack has a hole in it, you’ll come out empty-handed – but that’s not the school’s fault!”

CHILDREN’S PROGRESS

As a parent, Zote was very demanding. This was evident with his first child, Ibrahim, who excelled from first grade until university. I started school three years later. I knew that in our house, nothing but the maximum grade, a “five,” was acceptable. But boy was it hard to get those “poor fives.” The esteemed professors of that time would not give away a five for the life of them. I’ve never known stingier people! That’s probably where Gjirokastra’s reputation for stinginess comes from…!

THE GRADE AVERAGE

Ibrahim’s report cards continued to be filled with fives. He finished primary and middle school and started high school. Evaluations were done in two separate semesters. Zote was very upset with the first semester results because of one grade: a four. In Physical Education. It was the first four. The truth was that Zote’s son was small in stature, and the teacher’s evaluation was not only fair but kind. But try keeping a four! The rule was broken.

Zote wasn’t just being formal. He foresaw that this would lower the boy’s average and make it harder to get a university scholarship. He needed a report card of straight fives to fight for the right to higher education. Time proved him right.

He waited for the P.E. teacher to visit the bookstore. Zote knew his son couldn’t do more. He could fail the “vaulting horse” exercise any day. It wasn’t his fault; Zote himself had made him smaller than required. Where were his eyes?! You can’t do things with your eyes closed!

When the teacher came for his newspaper, Zote asked about his son. The teacher spoke highly of him but noted he didn’t meet certain age-related physical standards. Zote expressed his concern that the P.E. grade ruined the whole record. He couldn’t say “straight fives” anymore. The teacher remained professional, arguing that giving a five just for showing up would devalue the subject. Zote had to find an individual solution, so he turned to humor:

“I wonder why that boy isn’t performing well. At home, he walks on a rope like the acrobat Ali Xhixha, and most importantly, he has never fallen. He shows great stability.”

“How is that possible?! No, that’s impossible!” said the teacher, feeling embarrassed for failing to notice such acrobatic talent in his student.

“Of course it’s possible! He crosses it every day,” Zote said confidently.

“Forgive me, Alizot, but where do you tie the rope? How long is it? How high off the ground?” the teacher asked in amazement.

“Actually, instead of a rope, I draw a chalk line in the middle of the floor and make him walk on it,” Alizot finally explained.

Everyone in the bookstore burst into laughter, realizing the “acrobatics” were Alizot’s wit, not his son’s skill. The teacher laughed too. He got the message. As a parent, Alizot was aware of his son’s limits but asked for a formal exception because, as he put it, he wasn’t planning on sending the boy to the Institute of Physical Education.

WHAT IS THE WORLD?

Alizot’s daughter, Liljana, was appointed as a geography teacher in the village of Nepravishtë. She traveled daily by “couriers” – ordinary transport trucks with benches in the back. It was a privilege to return home every day, so she brought the students’ homework to grade at home.

One day, Zote asked Lulu how interested the village children were in learning.

“They are good, Zote. Some are excellent, but there’s one who doesn’t study at all. I gave him a ‘two’ (failing grade) on today’s written test.”

“What was the test about?” Zote asked.

“It was 4th-grade geography. The topic was ‘The World: What is the World?’. Everyone wrote two or three pages; this one wrote only two lines! I gave him a two, and even that was generous!”

“What did he write in those two lines?”

“Oh, you won’t believe it – it’s actually funny,” Lulu explained. “He wrote: ‘The world is a mess (rëmudhë) of dirt and water…’”

“Bravo!” Zote shouted. “He’s a clever one; the rascal understood it already! He’s right. That’s exactly what the world is: a giant mess on all sides. He deserves a solid five!”

“How can I give him a five, Zote, when he didn’t write a single word from the lesson?”

“Don’t you dare give him a two?” Zote ended the conversation.

WHAT GRADE ARE YOU IN?

He would liven up whenever students came to the bookstore, especially the younger ones. He served them with special pleasure, energized by their sincerity and desire to learn. But he loved to tease them. He asked them various questions, talking to them like a peer.

“What grade are you in?”

“Third grade,” the student might answer.

“Whoa! When did you go to the third? Last year you were in the second!” he would ask with feigned surprise.

The students would be confused at first, then clarify seriously: “Yes, xha Alizot, last year in the second, this year in the third. Exactly!”

Once, he got stuck with one student. Zote asked the formulaic question:

“What grade are you in?”

“Fourth.”

“But when did you go to the fourth? Weren’t you in the third last year?!”

“No, xha Alizot, I was in the fourth last year too, but I failed because the teacher hated me!” explained the student, proving different from the others.

Zote was left as confused as a student. He was caught completely off guard. And by whom? A “repeater”!

“He broke my formula,” Zote said. “The rascal got me!”

FRENCH

I once met Telo Mezini’s son, Bido, a doctor. He came to the enterprise where Ibrahim and I work to discuss hygiene taxes. He was happy to see us and wanted to talk about Alizot. He remembered him well for his kind communication with students and his humor. One case stood out:

“I went to the bookstore to buy books and notebooks. I was also looking for an extra-curricular book in French, as we were studying French in high school,” Bido began.

“‘What grade are you in?’ Alizot asked. ‘Which teacher is teaching you? What method are you using?’

I answered every question. Then he tested me: ‘How do you say this expression in French?’ and he said a simple phrase in Albanian. I don’t remember the exact phrase, but that doesn’t matter. I formulated it in French, but I wasn’t entirely correct; I got tangled up, corrected myself, got confused, and felt somewhat ashamed.

Alizot, who was waiting for that moment, cut me off with a laugh:

‘I thought higher of you, but you didn’t turn out as I wanted. How is this possible? In France, even the most lost (lowliest) peasant speaks French better than you!’

Alizot gave me his regards for my parents, and I left upset. All the way home, that comparison haunted me. I’d rather have received a bad grade in class than fail to answer Alizot! I went home and told my mother what happened. She listened and laughed.

‘You fool,’ she said, ‘didn’t you realize Alizot was teasing you? Don’t you know that French peasants don’t speak Albanian?’”!!/Memorie.al

Continued in the next issue…