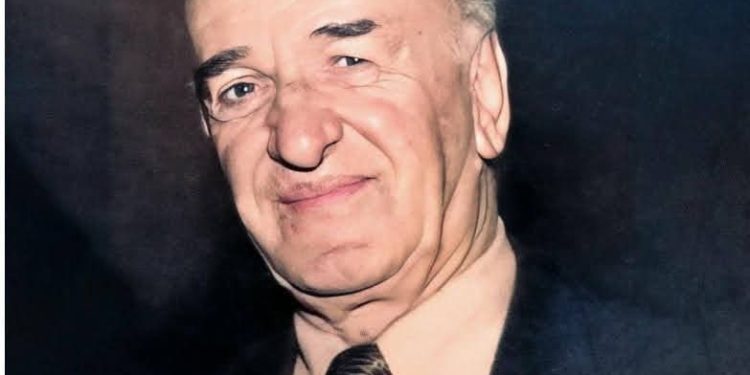

By Ahmet Bushati

Part twenty-seven

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Shkodra in the first years under communism

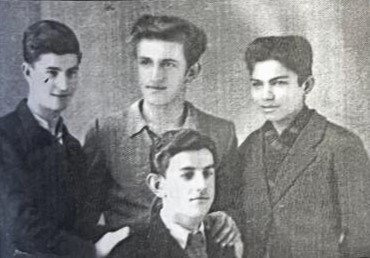

The Anti-Communist Movement of the Shkodra High School

“Nothing happened”, “It’s a shame that the neighbors are listening to us”, etc. When I returned to the small room, I found my father completely covered in blood, blowing smoke after thick smoke from his mouth and nostrils and, of course, unable to utter a single word, even formally. Words and strength had run out there on my lips, an hour earlier. Two or three times I tried to talk to him enough to speak, but to no avail. But with the intention of encouraging him, I was absent-mindedly leafing through a book. A “blackness”, although he had not died, had covered our house.

The cramped stay in that small room soon became unbearable for everyone, and then one after the other, including my father, got up and went in silence, supposedly to sleep in the large room, where in the solitude of their mattresses – as they would tell me years later – they had never stopped crying, each one shedding more tears and sobs than the other.

When, after seven years in prison, I returned home, especially my mother and aunts, but also a sister who had raised me at that time, would tell me that my father, after having fulfilled his duty as a citizen with me that evening, had become very weak from the day after I was imprisoned. Apparently, that stone he had placed in place of his heart the night before in our meeting had fallen away immediately, causing that man to start speaking only as a parent, and the courageous messages he had given me the night before had perhaps begun to seem somewhat harsh to him, and to make him afraid for his son’s fate.

“With no other man in the house and surrounded by a dozen women, with no one to come and with you in prison, Emin was destined to play with his mind from one day to the next,” they would tell me and tell me how, during the first month of my imprisonment, night after night, after an hour of lying down to sleep, he would take them for hours and hours, walking up and down the yard, inhaling tobacco without stopping, and the “uff-uffs” of his sighs were so uncontrollable that even the people in the house could hear them.

If they continued to tell me about that time, they would thank with great spirit and gratitude a poor villager from the village of Shirq on the Buna Coast, a certain Zef Ndoc, a loyal friend of my father, who during that first month, so to speak, had become “one” with my father, eating with him, sleeping with him and even taking him with him on his nightly walks around the yard.

“Zef who caused a problem that Emin had not thought of”, – my mother and aunts would tell me. Such was that dark time when each new imprisonment would mark a further wound in the sensitive and hardened soul of the majority of Shkodra citizens, and a real pain and sadness would cover especially the wide circle of relatives and friends that the house of the arrested person had. In connection with the above, I would like to at least recall the deepest pain that a grandmother of mine, widowed at a very young age, had suffered, who during my years in prison, had prayed day and night for me, and as a mother of hers, for as long as she had continued to have me alive, had turned to her daughter day after day with pain and as if in wonder, saying to her: “Who took our son!”, “But who took our son”?!

When the Berlin Wall fell, I heard an Italian radio station interviewing a citizen from East Germany, who, among other things, would claim: “The secret police of our former communist state, presented me with the alternative of either opening the way for the future of my only son, by agreeing to sign the declaration by which I would place myself in their service, or, by not signing it, to remain a good German, as was my duty, but to deny my son a future. I preferred my son’s future, by humiliating myself as a German and signing the declaration”!

Although such a case cannot be generalized, the moral constitution so deeply rooted among the Albanian citizens of that time deserves to take its rightful place in history. The generations that come after us will continue to teach children in schools what the Illyrians were, the Spartans and their Thermopylae, the Romans and their state organization; they will talk to them about Skanderbeg and our rebirthed and others and others, but also about these men, about our parents who fought the war without weapons, who suffered so much and without feeling, who sacrificed everything for us, their sons in prisons, as well as about the families that kept them alive with a thousand difficulties.

For those who valued honor and good name above all else, those who, so to speak, slipped anonymously into history, because they were more numerous, but also because they would not want to be seen for anything and in any case; For those determined and very wise people, who in the long anti-communist resistance of a people, in one way or another, served as small but strong points of support and reference, history should have the duty to teach future children, as a sign of respect, what they, their grandmothers, were.

As inevitable as my imprisonment would be, it had made the last days boring for me, and the very stream of life seemed to pass by rather gloomy. The sadness and the extremely difficult survival that I was leaving behind in my family, as well as the trial that awaited me, was a concern that my family and no one would ever understand, although the day I would cross the prison threshold, strangely enough, it would seem to me that I had been freed from an anxiety that had tormented me during that last time.

When I entered prison, I would leave Shkodra, our “mater dolorosa”, miserable and sad, barely prolonging the days of a life brutally murdered by communism. Until that day, three years and two months had passed since Shkodra had lost its permanent smile and the citizens consoled themselves only with the words: “God is great and will think of us too”, and found some kind of momentary peace even when they uttered curses like; “God, destroy these people”! etc., etc., like these.

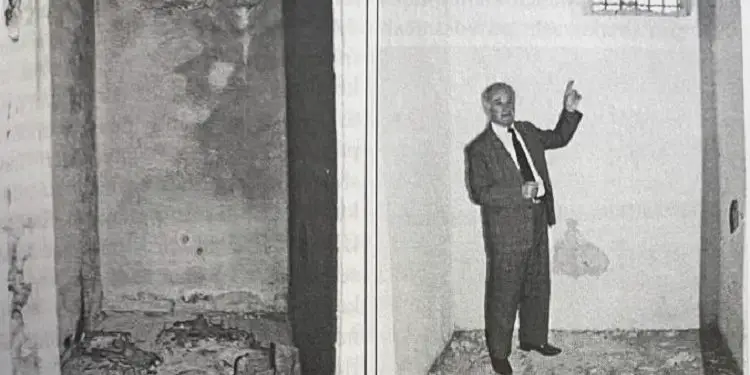

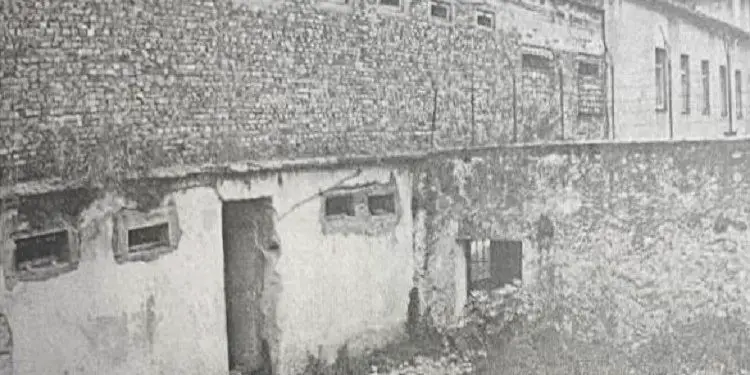

Shkodra, a shadow of itself

When I was entering prison, I was leaving Shkodra crumbling under the heaviest weight of a savage terror imaginable. The prisons were full, so much so that the people spoke: “home and prison”, or; “no one is left out”?! The misery was also deep. People had nothing to eat. Life seemed to have stopped. The communist regime had robbed us of everything: freedom, rights and well-being of our people. There was no more property and consequently no private activity. Enver Hoxha, in a sign of solidarity with Tito-Stalin, would be among the first from the communist camp to refuse the help of the Marshall Plan, a plan that would have quickly restored the large but war-ravaged economies of many European countries.

The agrarian reform had caused the small landowners, who were the majority in Shkodra, to cut off all ties with the village and to have no other way to provide for their daily bread. Even the villagers who had been given foreign land were not allowed to keep for themselves a single gram above the amount calculated according to their means, being obliged to hand over the rest of the production to the state. If someone happened to go to a friend’s house – very rare cases at that time – they would take with them a small piece of corn bread wrapped in a piece of paper.

The efforts and sacrifices that the heads of families would make to ensure the survival of their people are beyond description. Until the day of my imprisonment, for months in our house we ate only a handful of black beans for every lunch, a handful that my father had obtained with difficulty and not without risk. It was the third day and he forgot all about food. A friend of our house, who knows how many times, raising his eyebrows, would ask us as if with longing: “Will God willing, the time come again when we can eat meat and pilaf again?”

During the summer holidays of that year, a friend of mine had begged me several times: “Aman, Ahmet, take me to the village of one of your friends one day, so that I can say that I have filled my stomach for once.” Above all, these did not happen as a pre-war period, since after the war, excluding the difficulties of road traffic, due to the lack of bridges destroyed by the Germans at the end of their stay in Albania, for the rest, the Albanian economy had generally emerged from the wars healthier than it had been before it began, but it was the regime that, in poverty and misery, had supported its political and ideological success.

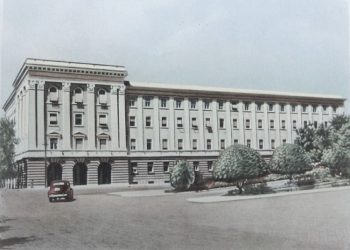

The magnificent bazaar of Shkodra, which once had been bustling with the work of its two thousand five hundred shops, had been needlessly turned into ruins and a cemetery. Even inside the city, dozens and dozens of other shops, like blind eyes, had lowered, as the case may be, their roulettes or tarabats, as evidence of their forced death. Shkodra, surely, was paying communism more than others for its written life twenty-three centuries ago, having begun what it had begun when it had been the capital of an Illyria that stretched from the tip of Dalmatia, down to deep into the Greek Gold.

That Shkodra was the city that centuries ago, through its skilled merchants, had beaten the routes of the Adriatic, Mediterranean and Aegean seas; and that under the rule of the Bushatlij family, had also been the capital of a vilayet larger than half of Albania; that the country was self-governing by laws, although under the constant threat of Istanbul; Shkodra, which at the time of the League of Prizren had 50,000 inhabitants and which, until the Italian occupation of the country, had hundreds of different commercial units, with banks in the city and an old bazaar, with hotels and electric companies, bus agencies, tobacco, flour, pasta, alcohol, ice, soap, fabric factories, currency exchange offices, etc., etc., and which also had a fiscal system respected by all.

Shkodra, where several temporary newspapers were published regularly, where there were for many decades, and even for a century, museums, libraries, theaters, cinemas and where all of the above, had been expanded and modernized even more during the occupation, while at the time when I was going to prison, this Shkodra of ours, a mortal enemy of the regime in power, had nowhere to eat, nor anywhere to work! The holidays that had been celebrated with such grandeur in Shkodra were only remembered symbolically.

People, of course, continued to get married, but there were no more weddings. Even during the last summer, the rivers Dri, Bunë, or even Kir, and with them the “dreamy” lake of Migjen, where they used to be, would still be, but who would have thought of them during that last summer?! Rozafat Castle, our pride, had not heard that for the last Shëngjergji it had hosted, – as it used to – visitors.

People with frozen gas on their lips, had not even been happy about the spring, which had not blossomed for them. It had not happened that even the mandate, which, according to tradition, in the life of life, had gathered with neighbors and shared among themselves and friends, to the dismay of time, that last summer, had had occasions to be traded like other fruits. Memorie.al