By Sokol Paja

Maksim Rakipaj: “As for Lubonja and Njjela, I judge that after the prison, only personal interests have taken precedence, Lubonja sometimes left, sometimes right, I have never understood Ngjela”!

Memorie.al / The writer Maksim Rakipaj, persecuted, persecuted, imprisoned and sentenced by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha for 15 years, confesses exclusively to the newspaper “Dielli”, Organ of the Pan-Albanian Federation of America “VATRA”, New York, the suffering, the violence, the torture, the eavesdropping, the investigation and the resistance in the communist prisons, of the innocent Albanians. Catholic, Muslim and Orthodox clergy, intellectual elite and ordinary people were barbarically massacred by the monist dictatorial system for nearly half a century. According to Maksim Rakipaj, it is time to set up a literary commission, with specialists, not communists, to select the best books of prison literature, to introduce them into the educational system. The new generation must definitely get to know the truths of the dictatorship. The evil that is forgotten is repeated. The Editor of “Dielli”, Sokol Paja, spoke with Maksim Rakipajn.

Who is Maksim Rakipaj, from the family biography, to the arrest?

Maksim Xhafer Rakipaj, married, with two children, was born in Vlora on July 15, 1951. He graduated from the Naval School in Vlora in 1972. He worked as a deck officer on ships of the Merchant Marine Fleet, until 1977, when he was arrested and sentenced to 15 years of imprisonment for agitation, propaganda and smuggling. He was released in September 1984.

He opposed the cooperation with the State Security; they left him without a job for 9 months. He started working as a miner in June 1985, in the coal mine in Manzë, Gërdec sector. After 1991, it resumed work on ships of the Merchant Marine Fleet. In 1996, he started working as Head of External Relations, Head of Protocol and Press Spokesman in the Municipality of Durrës.

In 1999, he resumed working at sea as a captain on various merchant ships. After 2002, he emigrated to Italy and lives in Lucca (Lucca, Tuscany). He has published the following books: “20 love poems and a song of sadness” by Pablo Neruda, translated from Spanish, TOENA publishing house 2003; “Prophet” Kahlil Gibran, translation from English, TOENA publishing house 2003; “Alive after the shipwreck”, prison memoirs, published by ISKPK (Institute for the Study of Crimes and Consequences of Communism), 2014; “Anthology of Arabic-Persian poetry” various translations, UEGEN 2015; “Trilusa m’Tirône” translation, UEGEN 2015; “Bukowski poetry”, translations from English, 2015; “The Complete Sonnets of Shakespeare”, translation from English, ADA publishing house, 2016; ‟The Prophet and the Garden of the Prophet” by Kahlil Gibra, translation from English, Toena publishing house 2016; “Kali Valltar”, by Jo Jo Moyes novel, translation from English, UEGEN publishing house, 2018; “I Survived”, reworked edition of the book “Alive after the shipwreck”, Publishing House “Two easts two wests”, 2018; “Anthology of Nobelist Poets”, Publishing House “UEGEN”, 2019; “Anthology of Dissident Poets”, “Jozef” Publishing House, 2019; “Poems from Maram Al Masri”, translations, “Jozef” Publishing House, 2020; “E Sigurt (Safe)”, novel by S.K Barnett, translation, Publishing House “Jozef” 2021; “Skin Color”, “Communism and the Logic of Beauty”, nonfiction by Manning Johnson, translation, “Jozef” Publishing House, 2021; about 20 titles.

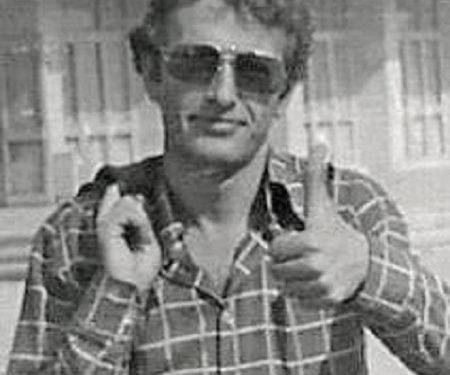

Maks Rakipaj, 1 month before the arrest by the communists.

Maks Rakipaj’s confession: The National Liberation War was a fratricidal war commanded by Yugoslav emissaries!

The war, which the communists call national-liberation, I think was more of a fratricidal war commanded by the Yugoslav leaders. My father started the war as a ballistician at the beginning of 1943 and after three months, he became a partisan along with two brothers. He was wounded twice; in 1944 he was admitted to the Communist Party. After the war, he graduated from the Officers’ School, after that school, he served as an officer in the Artillery.

In 1955, the government arrested the two older brothers, my great uncle, Njaziu, suffered 17 years in political prison, most of the time in Burrel. In 1956, they declared my father, my grandfather, Sabri Rakipaj, a kulak. After that year, my father served only in Xenjo’s army, with soldiers who came from those who were called “declassed”, until they removed him from the army in 1960.

In those years, I never knew if I had a “good biography” or a “bad biography”. I graduated from the Naval Officers School, afraid of being kicked out. My father was a communist, but my grandfather was a kulak, a politically convicted uncle. What was I?! I worked with all my heart, like the one who left an honorable name wherever he worked and many details are in my book of memories “Survivor”.

At least six months before the arrest, I felt stalked. Since I was going overseas as an officer in the Merchant Navy, it was easy for me to claim political asylum wherever I wanted. Why wasn’t I arrested earlier? Several times I had provocations to escape, from some who pretended to be my friends. So they knew my opinion, I wanted family more than comfort and my life.

Rakipaj: How did I get the first signals that I was going to be arrested and why didn’t I escape?

Therefore, even when I received certain signals that I could be arrested, I did not make any effort to escape, because if I ran away, they would have taken my soul, my mother, my brother and my sisters. They arrested me and the other officers of the ship “Durrësi” at the end of April 1977. Those were the years when the communist government had begun to eat “their own”. I was in the middle, both for them (the communist father, they expelled him in 1976 for “mitigating the class war”) and against them (grandfather kulak, an uncle 17 years in political prison).

But during the investigation, I was treated as the only real enemy of the people’s power. Here are the words of my interrogator, Spiro Spiro: ‟You are the real enemy in this group! You! Kulak grandfather, two uncles convicted, your father expelled from the party! You grew up with this spirit! You have drawn others to the path of enmity! They are lost, you are the real enemy”! “What is special about your story”? – was one of the questions.

I have often thought about this. Aladin Kapo (who was and is my close friend), grandson of Hysni Kapo (no. 2 in those years, after Enver Hoxha), served as first officer on the ship “Durrësi”. Aladdin was arrested with us. In those years, it was known that the health condition of the dictator Enver Hoxha had worsened a lot. Two were thought to be successors after the dictator’s death, Hysni Kapo and Mehmet Shehu, because Ramizi was in the shadows those years. Hysniu was eliminated in 1979, Mehmeti “killed himself” in 1981.

Perhaps after the arrest of the nephew of Hysni Kapo, on political charges, the hand of Mehmet and his “partners” was hidden. The rest of us were just for decoration, to make it more convincing. Aladdin and I were given 15 years in prison each, the other two 12 and 11 years in prison. They called me the leader of the “hostile group”. According to the investigator Spiro Spiro, this was done so that the case did not get the name “Aladin Kapo and others, because it sounds bad among the people”.

The literature of prison memories, confesses and unmasks the communist hell

After the 90s, this type of literature, unknown before, began to develop. Memoirs were written by those who had written and published before imprisonment, but most of the authors of this literature were beginners in literature. Many of them are my fellow sufferers, others I know only by name. I think it’s time to set up a literary commission, with non-communist specialists or those connected to the dictatorial regime, to select the best books of this literature to introduce into the educational system.

The new generation must definitely get to know the truths of the dictatorship. The evil that is forgotten is repeated. If I’m not mistaken, one of the first books of this genre was the book by Fatos Lubonja, titled “Rebirth”. But the two books of Visar Zhiti, “Rrugët e Burgut” and “Ferri i căra”, where the hand of the writer is visible, had the biggest echo. I also read with pleasure and curiosity the books of my friends: Gëzim Peshkepia, Hysen Haxhia, Gëzim Çela, Skënder Tufa, etc.

The Institute for the Study of the Crimes of Communism, under the direction of Mr. Agron Tufa and Çelo Hoxha, with a series of publications written by former political prisoners. The books were published and distributed for free at the expense of the Institute; many of us do not have the financial means to publish in publishing houses. My book of prison memoirs entitled “Alive after the Shipwreck” (the title of the book was suggested to me by my friend Visar Zhiti), was published by this Institute in 2014. From my friends who wrote in prison and showed me their creations , were the late Zydi Morava, the unforgettable Gëzim Medolli, Hasan Bajo and of course, Visar Zhiti.

Friendship with Visar made my love for poetry reborn. I didn’t write there, I only translated. When I was released, I had about 35 poems translated. My first attempt at translation was the poem “The Invincible” by William Ernest Henley. It was not easy to write in prison because there were also spies in the service of the command. But we also had friends who looked after us and we looked after them when they wrote. We also helped them to get the writings out of prison. So far, no government has taken any measures to introduce this type of literature into our education system.

Years of imprisonment, inhumane conditions, mining work, lack of food and police violence in camps and prisons

We have all seen movies, read books about the concentration camps of Hitler’s time or about the gulags of Lenin and Stalin. During the prison years, I was forced to live in three camps: Ballsh, Spaç and Qafë-Bar. In addition, I had the chance to know old convicts who had been in other camps (such as the Malik swamp camp that neither Hitler nor Stalin could set up), who would have been the envy of German and Russian specialists of concentration camps.

Old prisoners said that in the first years at the Ministry of the Interior, a former SS (German Nazi), who was wanted by the Czechs for war crimes, worked as a prison specialist. I also read the book “Last Station – Auschwitz” by Eddy De Wind, Dutch Jew, with leftist beliefs, survivor of the Auschwitz camp. Only the crematoria were missing in the Enverist camps. Food was scarcer and worse than in Auschwitz. In the Ballsh camp, the menu was this: breakfast: a kind of fat-free soup with leeks, cabbage or tomatoes, etc., boiled.

Lunch: one day of pasta juice, one day of rice juice and one day of grosso juice, with a grain of rice or grosso floating in the tuk, depending on the day. Dinner: tea (burnt sugar, the juice of which was served for tea). And according to the norm 600 gr. bread, which in fact did not even give 500 grams. The elderly, the sick, died of hunger and lack of medical care. When I was in the extermination camp in Ballsh, the former vice-president of the Durrës Internal Branch, the criminal Kapllan Shehu, came to ask me to cooperate with the State Security. My objection and the way I responded irritated him beyond measure. Within 10 days, I was transferred to the legend-infamous Spaçi camp.

The next day I started working in the mine. Real hell, especially the first few days. When the next month started and the monthly work schedule was made, I was assigned to work as a miner with a hammer. In Spaç, work was done in three shifts and with three working groups: a miner and two shovel workers. The workers cleaned the work front from the crack of the previous shift, which they loaded into wagons with a capacity of one ton. The norm was eight wagons, but no matter how many ore wagons there were, the front had to be cleared so that the miner could place the wooden, iron or concrete armor and then make the holes with a hammer.

It was deadly work. Wet drilling system to avoid dust was missing. There are many survivors who suffer from various diseases because of that work. There are not a few who died prematurely, or from accidents and poisons in the mine. The dead were buried in the cemetery of the respective camp, and the family had the right to receive the body, only after the unfortunate man had completed his sentence. About police violence in prison, one interview is not enough. Police violence was the cause of the outbreak of revolts: Spaç 1973 and Qafë-Bar 1984.

State security in prison, revenge against the “broken”!

In 1979, Albanian Radio Television broadcast the film “Skëterrë ’43”, with a script by Bashkim Shehu, the son of the bloodthirsty Prime Minister, Mehmet Shehu. The film, as I recall, opens with a conversation between a Fascist Quaestion specialist on prisons and a senior party leader, where the former elaborates on the idea of the camp’s operation:

“The core of the camp will be those that we will break in the investigator – these are the rats and they will be an example for others; then they will be workhorses, it doesn’t matter the yield they bring, it is enough to work so that they don’t have time to think. Then we will add a lot of people with low morals, ordinaries, etc. We will instill in their brains that these are not people, but caterpillars, worms, we will make them not have respect for human values and for themselves”.

In short, this was the duty of the State Security in Enverist camps and prisons. To break people. Enticing them with easy jobs that had some profit. The convicted leaders of the camp were all Security spies. Such were also those who had privileged jobs, such as: in the kitchen, brigadiers, normists, etc. But there have also been cases when the “broken” changed their minds. The insurance’s revenge in these cases knew no bounds, not only re-convicting them, but they also took revenge on their family members.

Their violence has also caused suicide. I was an eyewitness in Spaç, in 1979, when one of the “broken” tried to overcome the triple fence with barbed wire, to force the soldier of the home guard to shoot him dead. In that case, I remember the soldier begging the convict: “Don’t! Please don’t cross the next fence! I don’t want to kill you”! And he didn’t kill him; he just slightly wounded him in the leg. Word spread that that soldier was punished.

From Father Zef Pllumi, to Lluk Kaçaj, memories and conversations with the imprisoned clergy!

I remember that the Catholic clergy were more afraid of ordinary prisoners, maybe the violence against them in the interrogator was more severe. I knew some Catholic priests, but they avoided religious conversations and only if you trusted them, would they answer when you wished them Christmas or Easter. I knew Baba Mehmet, the dervish of Teqe e Frashëri, since I am also from Përmet and Baba knew many people from my relatives. He was a cultured man; he had studied in Istanbul and even had the chance to meet Qemal Ataturk.

December 1978, the end of the year holidays was approaching. In the Ballsh camp, despite all the misery of the prison, a kind of joy and hope could be felt in the eyes of the prisoners. I met the artist Mehdi Prodani there, the best guitarist in Albania, the brother of the composer Agim Prodani. Having fallen for the guitar before, there was no better opportunity to learn a little from the great master of the guitar in his spare time. The medium was immediately ready. I knew solfege, so it was easier for him to help me.

He wrote me different parts, at first easier, and I practiced in an alcove where, a former priest, silently worked on repairing the old books of the camp library. When I asked him for permission to practice where he worked, the priest raised his head a little, looked at me and nodded yes. Without speaking a word.

I went there almost every day. Professor Nikollë Daka told me that the former priest was called Father Zef Pllumi. There was another world-class artist in the camp. Bass Luke Kaçaj. I liked to listen to him when he spoke, Luka, especially when he spoke to his domino game partner, in that deep bass voice: “Jahooo…”, the window panes shook from Luka’s voice.

One day Luka sang under his breath “Stille nacht” (quiet night)… I and Medi Prodani listened to him hypnotized…! – “Medi, please write this for me, I want to learn it…! – Definitely, – he promised me. With the music sheet in my hand, I went to the alcove of my beloved Zef Pllumi. I worked for several hours. In the end it turned out well, I also realized the “campanella” that Mediu had marked for me…!

The unforgettable Zef Pllumi, who was listening without moving, spoke to me for the first time: – Well done boy… this song, the most beautiful in the world, dedicated to Christmas, was written by a village priest, the music and words were written by his teacher small village somewhere in Austria…! – Merry Christmas, – I said in a low voice…! “Thanks, happy to you too, thanks once again for the music”.

Visar Zhiti, a special fellow sufferer

I have had and still have close friendships only with Visar Zhiti, whom I have always met as a brother. As for Lubonja and Njjela, I judge that after the prison, only personal interests have taken precedence, Lubonja sometimes left, sometimes right, I have never understood Njjela. For Visar, I am especially happy with his successes in literature. It is unfortunate that for the appointments of former political convicts to important positions, the parties that have had the next power, have preferred (with some rare exceptions), the former “broken ones”.

Back in time, events and people, the time of horror

I think that the communist regime, established in Albania with the approval of the Great Powers, was the most severe punishment for our people, when they threw little Albania into the communist camp. We experienced a diabolical, inhumane experiment, and from what I understand following the events there, that experiment is not over yet. After World War II, the process of denazification began in Germany.

The timid process of decommunization in our country was violently interrupted by the events of the ghastly year ’97, which were devised by the long hands of foreign secret services. During the years when I was working as a sailor, before I was arrested, I had the opportunity to see other communist countries such as: Poland, East Germany, Romania, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. Our standard of living and basic human freedoms were much lower. None of those places were surrounded by barbed wire.

Only here (and in the former Soviet Union of Stalin’s time) have dissident poets been imprisoned, shot and even hanged. When the communist world was starting to change after the Reagan-Gorbachev meetings, in 1988, the poet Havzi Nela was hanged here. The president of that court, instead of being punished, was appointed to the highest hierarchy of justice. When the changes started in us, after 1990, I was very optimistic. I thought that within 5-10 years Albania would become a prosperous country.

I never wanted to leave the country; I wanted to contribute to the progress of the country. But I saw that our rulers were only thinking about their pockets and interests. Not for the prosperity of the country. I was disappointed. That is why I settled in Italy after 2002. Today I am very pessimistic. Every time I go to my homeland, I see poorer and poorer people. Youth tends to leave. Only the elders are left. And increasingly rich arrogant rulers. And unfortunately, the world cheers. Therefore, today I am very pessimistic. Memorie.al