Part Five

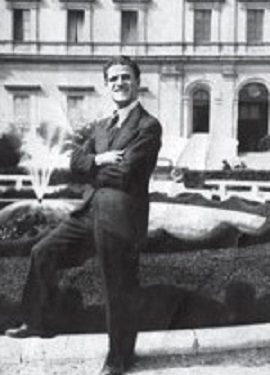

Excerpts from the book: ‘ALIZOT EMIRI – The Man, the Bookstore, and the Noble Mirth’

A FEW WORDS AS AN INTRODUCTION

Memorie.al / When we, Alizot’s children, told “Zote’s” (Alizot’s) stories in joyful social settings, we were often asked: “Have you written them down? No! What a shame, they will be lost…! Who should do it?” And we felt more and more guilty. If it had to be done, we were the ones who should do it. But could we write them?! “Not every person who knows how to read and write can write books,” Zotia used to say whenever he handled poorly written books. When we, Zote’s children, were discussing this “obligation” – the Book – we naturally felt our own inability to carry it out. It was not a task for us! By Zote’s “ruler,” we were incapable of writing this book.

Continued from the previous issue

IMPRESSIONS AND MEMORIES OF ALIZOT

Prof. MUZAFER XHAXHIU: A LIFE LINKED TO THE BOOK

A conversation with Professor Muzafer Xhaxhiu

In January 2011, I went to the home of Mr. Muzafer Xhaxhiu. He was waiting for me! He took me close and wanted to talk. He had read Mr. Nasho Jorgaqi’s piece, “The Noble Mirth of Alizot Emiri.” He had liked it very much.

-“He wrote it beautifully!” – he told me and continued: “Nasho is a man of letters.” The writing prepared by Professor Muzafer himself had been taken by his son, Artan, to be typeset. In the meantime, he remembered a story about Alizot and wanted to tell it to me:

-“Together with me, my uncle’s son, Skënder Hajro, often came to Alizot’s shop. One day, Alizot asked me: ‘Why hasn’t Skënder come to see me?’ I said: ‘Skënder, these days, had his sister’s wedding to a man from the Shapllo clan, whose family immigrated to America.’ – ‘Have they been in America for a long time?’ – Alizot asked me.

‘Since the beginning of the twentieth century,’ I explained. Alizot shook his head thoughtfully and sympathized with their plight: ‘The poor souls go there, but how their fate turns out where they go, only God knows.’

-‘Eeeh, that business is a matter of luck. Some get settled, some…’ – I continued the conversation. ‘I want to tell you something, Alizot, I have heard it many times from my mother: A man from Gjirokastra had returned from Anatolia, where he had lived for years.

When he came back to Albania, so as not to go into exile (kurbet) anymore, someone asked him: ‘Well,’ he said, ‘what did you do there in Anatolia all those years?’ – ‘My luck went well,’ he replied. ‘You don’t know, but I will tell you. With what I earned, I have bought two estates here in Gjirokastra: “Terelengu” and “Çullon”.’

(Tereleng = without a penny! – in the spoken language of Gjirokastra. Çullo – the name of a stream at Zalli, beyond Palorto).

The one who asked was surprised by this answer and said in the same humorous tone:

-‘Well, why don’t you say so! Your time in exile didn’t go to waste; you’ve made quite a fortune!’

After the telling of this story, Zotia reacted, having felt the pain within it:

-‘That emigrant must have been clever! Fate truly didn’t help him gain anything, but at least the poor man didn’t lose his mind. That saved the poor soul!’

Zotia, my boy, valued the mind all his life, not money; that is why he was always smiling and full of humor. He felt very rich!! He had defeated poverty with the wealth of the mind!”

-“What relation do you have to Lato Emiri?” – Prof. Muzafer asked me later.

-“We have heard good words, but we are not related to them,” – I said.

-“Then which ‘Emirs’ do you belong to?” – the Professor asked me again.

-“To the Emirs of Kuwait,” – I answered him in all “seriousness.” He turned his head and looked at me with a smile. – “That is what Zotia told us,” – I continued. – “But what of it, they haven’t given us the share that belongs to us from the oil wells in Kuwait. They have forgotten us! At the very least, they could have given us just one oil well!” I went on, imitating Alizot. – “This was Zote’s ‘worry,’ which he always recalled with humor!” – I shouted, because the professor had great difficulty hearing.

-“I remember these cfina (wedges/stings) of Alizot since Zog’s time, in their shop,” – the Professor intervened, having understood our “plight.” – “Do you understand what they call a cfinë, Alizot’s son?” and, without waiting for an answer, the Professor explained: “Cfinë is what they call a wedge (pykë). You know that, right?”

-“I know it differently – that we call a wedge a cfinë in Gjirokastra!” – I said. The Professor laughed with the pleasure of a great Gjirokastrit who has immortalized the special cultural tradition of our city with his precious work, “The Dictionary of the Gjirokastra Dialect.”

-“Uuuu, I put cfinë in the dictionary, didn’t I?” – he turned to his wife. And he immediately opened the dictionary with the worry of a creator. He focused on the dictionary and found it. – “There!” – he said – “I put it in.” He was relieved! – “When I remembered a word from our dialect, I would rejoice, my boy, as if I had found a gold coin!” – he told me, his eyes shining as he relived that happy moment. It was the happiness of finding a people’s greatest treasure – their language.

He gifted me a dictionary, in which he wrote a dedication to Alizot.

-“Come see us again!” – he said, standing up to see me out with impressive respect.

-“I will come!” – I promised – “I will come with Alizot’s book!”

Prof. NASHO JORGAQI: THE NOBLE MIRTH OF ALIZOT EMIRI

(Threads of memories)

I remember my first meeting with Alizot Emiri as if through a fog. Over half a century has passed since that time. Back then, I had just started working at the “Naim Frashëri” Publishing House, which was administratively part of an enterprise along with the printing house and the book distribution sector.

I remember a broad annual meeting with the booksellers that was organized, where we, the editors, were also invited. The Director of the Enterprise, who chaired the meeting, the unforgettable Spiro Xhai, after delivering the report, invited the participants to discuss.

A silence fell, which lasted even when the director repeated the call from the presidium for people to speak. Then, a clear voice was heard: “I propose that we speak in order, according to our salaries. Let those who have the highest start first.” The hall erupted in laughter, especially when I heard the director’s authoritative voice: “Alizot, stop the jokes. This is no place for humor.”

I turned my head back and saw a man of medium build with a smiling face who said: “I’m done.” During the break, I noticed that Spiro had put his hand on the speaker’s shoulder – who was completely unknown to me – and was laughing. I approached, and the director immediately introduced him:

“This is Alizot Emiri, the distinguished bookseller of Gjirokastra.” To which he replied: “Who has a salary three times smaller than the big director.”

This was our first meeting. Later, I would know him through everything I would hear from others. He would become an anecdotal character for me, because from time to time his words and deeds would reach my ears. Usually, such jokes came from Shkodra, but it turned out Gjirokastra did not lag behind. However far apart we were, it did not stop us from getting to know each other closely and becoming friends.

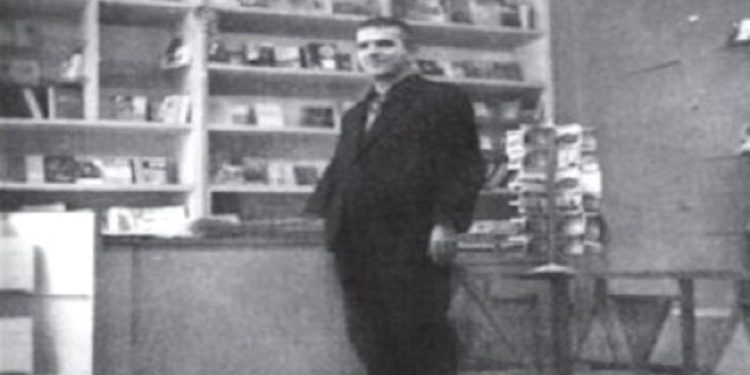

He came from time to time to our enterprise, while I rarely went to Gjirokastra. Only on official business, when the director took me, and in those cases, as soon as we got out of the car, we went to Alizot’s bookstore, which was in the middle of the cobbled street leading to the Qafa e Pazarit. These were joyful and spontaneous meetings that made the hours spent in Gjirokastra pleasant. Spiro, who loved him dearly, would pretend to criticize him, and Alizot would start talking and telling stories through humor that made us laugh and lose ourselves.

Unfortunately, of all that Alizot told, I have forgotten most of it now, and I consider this a loss of that humorous wealth that he created quite naturally, from time to time, in the most diverse situations. Certainly, from those distant times, only a few of the anecdotal events that I heard directly from Alizot remain with me.

First, I want to say that Alizot was a wise man of dignity; he had a personality that inspired respect for everything he said and the way he told it. There was nothing forced or banal about him; he was very convincing by nature and, most importantly, he had the sharpness, wisdom, and maturity of Gjirokastra, and this made his humor effective, convincing, and meaningful.

At that time, humor was troublesome – a double-edged sword and often dangerous – even more so for Alizot, who in the first years after liberation had been imprisoned for a spoken word. Yet, even under these conditions, after his rehabilitation, he could not escape his nature as a jester, his irony and sarcasm, which he passed on to others without malice, but which contained thought, rebuke, criticism, and certainly true humor. There were cases when he dared to take initiatives that could have cost him.

But the truth is that public opinion honored him; it valued his wisdom and his healthy humor. And not only the public, but also the party leaders and local government did not take it badly. They even say that Enver Hoxha knew him and would wave at him, laughing from a distance, when he came to Gjirokastra. Alizot even had acquaintances and friendships with some high-ranking Gjirokastritë, with whom, when he met them, he would make salty jokes.

Once, Haki Toska, a member of the Politburo, came to his bookstore and, among other things, praised him for how, before the liberation, he secretly brought and sold foreign leftist newspapers like “L’Humanité,” etc. “Well, even we have done something good,” – Alizot replied with a smile on his lips. “But who are these by the door, Alizot?” – Haki had asked him. Because on both sides sat several men, usually porters or the unemployed, who were reading the newspapers or a book that Alizot had given them. “The people, Comrade Haki, they are reading for free,” – Alizot had replied.

Then Haki had asked him for the book “100 Tales,” which had just come out. “How much is it?” “Fifty lek!” “Too much, Alizot!” “Half a lek per tale, Comrade Haki,” – the bookseller had answered. “And do you have Maupassant’s ‘Bel-Ami’?” – he had asked again. “I have it, oh, of course I have it, but did you bring your wife with you? Because that is a dangerous book for men.” Laughter had broken out, and in the end, Haki had told him: “Listen, Alizot, can’t you leave these quips aside for once? You have remained exactly who you were,” and he embraced him.

Another time he told me: “Something crossed my mind one day. I had a stock of the works of the classics of Marxism-Leninism left in the warehouse. No one was buying them, only very rarely, so I got up and went straight to the Party Committee. I waited until I went in to see the First Secretary. ‘Well,’ – he asked me – ‘what good news brings you here?’ Instead of an answer, I handed him a list of names. He widened his eyes. ‘What is this?’ – he asked me. – ‘They are the names of the members of the Plenum of the Party Committee and those of the People’s Council.’

– ‘And then?’ – he said. – ‘The matter is this, Comrade Secretary. The works of the classics have remained in the warehouse. No one buys them, partly because they cost money. Not even the cadres buy them, even though they are primarily for them. Therefore, I have brought the list of their names for you to sign and order them to buy them. Otherwise, they will remain as stock. It’s a shame, for whoever might hear of it.’ The Secretary paused for a moment and then burst out laughing. – ‘Where does your mind go, Alizot!?’ – he said.

‘But this is my job, Comrade Secretary.’ – ‘Clever work and bravo to you,’ – he said and signed it without hesitation, then stood up and shook my hand. It didn’t take long before, a few days later, after they had received their salaries; the ‘nightingales’ came one by one and bought the classics’ books that were sleeping. Some of them had found out about my trick and were laughing, while there were others who were not pleased and hung their lips!”

It happened, when we met once in Gjirokastra, that he told me another story. For a time, besides the bookstore, Alizot worked next door in the commission shop where second-hand items were sold. “A priest came to me one day and asked to buy a cassock (raso). I got up and handed him a black dress. He put it on and tried it. It fit his body. Apparently he liked it and bought it. He left, only to return a few days later with the dress and tell me: ‘Listen, Alizot, but this isn’t a cassock. It turns out it’s a woman’s dress?!’ I got annoyed and said: ‘But you, Father (uratë), you aren’t a child to be fooled. You had your eyes, your mind too, so why did you take it?

When he got even angrier. ‘You have deceived me,’ – he cried – ‘and I will complain!’ ‘Go wherever you want,’ – I said. – ‘And as for that deception you mention, you with your cassocks and those with their turbans, you have been lying to us a little bit all our lives. Let us, the people, lie to you for once.’ The priest left, but the word spread so much that those at the Committee found out, and one of the secretaries told me: ‘You did well to the Father.’”

The last time I met Alizot was in Fier, when he had retired and had come to see his son. We sat in the tourism café and settled into a conversation full of nostalgia, talking and joking. We hadn’t seen each other for a long time. I noticed that he was somewhat aged, but as always energetic and sharp-tongued. I was surprised when I saw that he had shaved his head and I couldn’t contain myself.

“What have you done to your head like this, Alizot?” His eyes laughed and he said to me: “Listen, how I should explain it to you. This head of mine has been unripe all my life. I decided to ripen it in my old age. I shaved it and I wander around in the sun with a shaved head. I think the sun will finally ripen it!”

I laughed with all my soul, just as I laughed for almost two hours that we sat together. From Alizot’s mouth flowed only wise words, full of meaning, with all sorts of subtexts, direct or allegorical, and, most importantly, with an unrepeatable humor. He told stories and I continued to laugh, forgetting time and everything else. In the end, still laughing, we parted, never to meet again.

It sincerely pained me when I found out a short time later that Alizot’s joyful heart had stopped. Now, when I remember him, I feel very sorry that many of his sayings and deeds I have forgotten. But his memory still lives in me, as one of the joyful memories of life, of a clear-minded and great-hearted man who radiated humor and noble mirth./Memorie.al

Continued in the next issue…