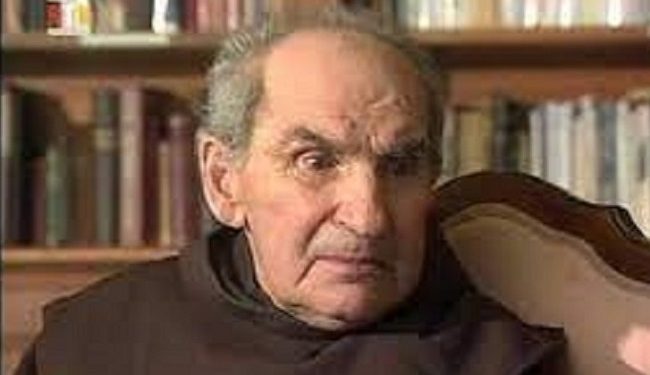

By Father Zef Pllumi

– Why did Fishta accept the academic title from the Italians and his last words in the hospital, shortly before his death?!-

Memorie.al / Father Zef Pllumi were among the last of that constellation of patriotic clerics, who endured the ordeal of communism for years. In commemoration of his name, we are extracting an interesting chapter of his life from the collection “History never written”. A bunch of memories of Father Zef Plum, related to one of the greatest figures of Albanian literature, Patër Gjergj Fishta, but also the most discussed, regarding his attitude towards fascism. Precisely for the latter, but also for his burial place, these memories of the cleric, who until the end, fought for the truth, shed light. And on the other hand, they bring back to our attention this multidimensional figure. Under the clergyman’s roof, lived the patriot, but also the writer with a fine observational pen. His book “Just show me”, has been described as the “Albanian Gulag Archipelago”.

When did I meet Fishta?

“History, never written”

When I saw Fishta for the first time, I had not yet formed the concept of time, so although it has remained indelible in my memory, neither the date nor the year can be recorded. Of course it was a summer day. My parents lived as livestock farmers, they went out with their sheep in the summer to Neck Tërthores, which borders the high mountains of Malsija e Madhe, with the high mountains of Dukagjin. Near an alpine lake, we had pitches. At that time, the Theth highway did not even reach Boga. Travel was usually done by horse. One day, as we were children, among those five or six stables, we were driving a carriage on the back of horses, escorted by three mountaineers.

When they came down, my aunt, like a god of spears, duel with an ambush; they hugged each other heartily and talked a lot, they went down together to Stani e Mira. It was called “Good Stan ” because my aunt, Pashko Toma, was counted among the good men of the mountains at that time, that’s why the cabin was covered with carpets, surrounded by dry walls with carpets, and it looked like a waiting room, which he only had it for friends. Childish curiosity pushed us inside the stan, to introduce ourselves to our new friends, but our mothers pushed us away, they told us: “Don’t come here, but go as far as possible, because Father Gjergj Fishta has come that pinches others’ tails; those who don’t have it get it, and those who have it, wait for it”! As small children, we used to look at each other’s clothes to see if we had tails or not. Also, from our nannies, we found out that the other friar was Father Anton Harapi, who in our childish imagination, for association of ideas, sent us to children’s fairy tales, about Harapi of Beledija, of course black and terrible.

But, when my friends left and dispersed, I benefited from my persistence and from the love that my aunt had for me, even more than for her own children, and that’s how I arrived and unlocked the door of the “Good House” , in which no one could enter. I threw myself into the lap of the aunt, who introduced me to my friends and ordered me to kiss them. I hated petting. From my aunt’s bed, I saw my great friend, whose eyes glittered in the stan’s grave. Two strange eyes, full of light and spark.

Even today, after many years, in my old age, I can testify that never in my life have I been without such powerful and enlightening eyes. I remember well Fishta’s caresses, that for the first time, I heard the word from his mouth; “chiripup”, with which he used to caress. But the other friar didn’t seem so black and rude to me, as I imagined Harap of Beledija; not only that, but when my aunt showed them my childish desire, to become a friar, that Harapi, removed from his neck a medal of Saint Francis and said to me: “Keep it! When you grow up, present this medal at the door of the College and they will accept it, but keep it, don’t lose it”! I entered the Franciscan College later, but still at a young age. The Franciscan primary school was adjacent to the Assembly of Fretën, where Fishta lived at the time.

Father Gjergj Fishta

In 1933, with a government order, all private schools were closed, and Franciscan schools also suffered this fate. At that time, the government bodies had given a big boost to the “Bird Youth” and the official greeting had just begun, with the hand on the chest. These actions were borrowings from totalitarian methods, which Fishta did not like at all. It was said that on one of these days, he left the Franciscan Assembly and went to visit a friend of his. You passed through Fushë-Çëlë, he walked with a limp, leaning on his thick stick. Some citizens, who were sitting there in front of the Great Coffee, to tease him, take a small seven-year-old child, give him a bunch of flowers and tell him to come out with money and honor “Alla Zogiste”.

When Fishta saw him caressing him, he told him in a loud voice, so that everyone could hear him; “O chiripup, you are still very good; that I have reached up to your chest, but I have reached here”! – And you put your hand like a child, but to your lips. Fishta fled to Italy: there was no more trust or security in a regime that opposed culture. After a few years, the situation seems to have been clarified after the decision of The Hague Court, and Father Gjergji returned to his homeland, to continue his gigantic efforts, in consolidating the education and Western culture of the people.

The Franciscan schools were reopened when I was somewhere in the first grades of high school. One day, Fishta, tue was held by his thick stick, go to class. We all went to camp, not only the students, but also the professor of literature. Fishta looked at us all, with a smiling face and cheerful eyes: “Sit down, boy”! – He said. Then he asked the professor: – “I came to see what literature you teach, but also grammar, like Father Justin”?!

-“Of course,” answered the professor, “grammar and syntax as well, but he gives the greatest importance to stylistics, and especially to literary compositions.” – “Very well,” said Fishta, “these must be the writers of tomorrow, and I wish I could read any of their literary works.” Yes, does anyone do poetry? There was complete silence. Of course, some of us would also have youth poems, but no one had the courage to present them to that great poet. The silence continued long and full.

– “Look, he told us, – I wish Albania to have many writers and poets, but this poetry is a gift of nature. When there is a lack of talent, this gift, then it is better to become doctors and engineers or even cobblers, than bad writers. A bad writer does a lot of damage to the people who read it.” The professor then told him that he was trying to give us the works of the best authors of world and Albanian literature, among which his name is one of the main ones.

– “Even Malcia’s Lute”? – Fishta asked. – “Yes, yes,” answered the professor. We have a guy here who knows it by heart”, and told me to get up. – “Which song do you know?” – “All”, – I told him. At that time, the complete work was not published, but only three booklets, with five songs each. – “Tell us the Kanga of Ali Pasha Gucia”! I put all my recitation skills to work and he liked it so much that, after saying “goodbye”, he turned to the professor: “If only I had that X.Y., I would record it on the gramophone”! – “For recordings, don’t think about it, Father Gjergj,” the professor told him. – That voice of yours, with the recitation of the Lahuta, will remain an eternal memory for all Albanians”. – “I would be the happiest, if I could listen to a young man, like this boy, recite ‘Lahuta’.”

It was about a recording on gramophone records, where Fishta himself recited two lute songs: “Vranina” and “To the Church Shnjoni”, from 1929 or 1930. Today, those gramophone records, with Fishta’s true genius, should be extremely rare. I had the chance to listen to some tapes, especially in recent times, but I can say for sure that they have nothing to do with the recording of the true genius of Fishta.

Later, Fishta was elected Provincial (Superior) of the Franciscans of Albania, for three years and then, quite old due to illness for years, he was assigned to the Assembly of Arra e Madhe, a suburb of Shkodra. Around this Assembly, there were vineyards and orchards, cultivated fields and beautiful meadows. With this calming environment, Fishta continued to work on his literary work. Participating in that small assembly were some of his other elderly colleagues, as well as P. Marin Sirdani and Father Justin Rrota. We students, almost twice a week, spent the afternoons in the premises of that Assembly, and so Fishta, when he was free, sometimes came and grew up with us…!

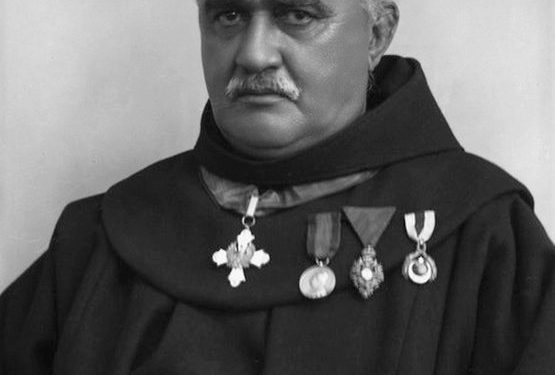

After a while, the Italian fascist occupation came. Only those who have experienced violence on their own back can understand more precisely what dictatorship is. Fishta at this time was in the Franciscan Assembly in Arra e Madhe. The fascists changed the King, they also changed the flag. Like all dictatorships, they also demanded the applause of the people and the humility of famous and influential people. They distributed coins, distributed decorations, distributed new ones. In that year, I was among the upper classes of the high school. Word spread that Fishta had also been named by decree as “Academic of Italy”. After a few days, it was decided that all the members of the Franciscan Assembly would go together to Arra e Madhe to congratulate Fishta. He welcomed us with candies and kumel. After presenting our congratulations together, one of the professors, P. Mëhill Miraj, went over and said:

-“Pater Gjergj, here are all your students. Here I was expressing the opinion of all my colleagues and your brothers: as much as your name as an academic was good for us, it was also bad for us. From you, we all learned how to love Albania and how to be patriotic. All of Albania, as well as the Italian fascists, know very well that you were against them. Together we have decided with him to make this proposal: just as you returned the decree of decoration, which was sent to you by the Italian authorities, you were told that; ‘It’s not a decoration for me’, also, take back the title of academic. This much we know and this much we can say as your brother, as your student and as your son, don’t take us for granted because you are our honor”. During these words, Fishta fell into thought.

– “Listen, – he said, – brother of my son. I have not changed, but I am the Father Gjergj that I have always had. You know very well how much I love Italy here. So long, even the fascists understood it themselves. Don’t think that this title was given to me to honor me, but it was given to me to intern me. The Latins have an old axiom of their politics: Just as they are deporting many other Albanians, they are also deporting me, because according to the Statute, every new academic has the duty to behave with me for six months, and you held conferences in the high institutes of culture. In this way, they love their work and at the same time throw dust in the eyes of the world, the Albanian people and me.

I am an old man today; heart disease, it has happened to me a lot in these last months. Those lessons of mine, which I once gave you, I wanted you to put into action today, while I am not good at facing prison, exile or escape. But I am promising you that I will never humble myself before foreigners, the rod of the Albanian. Indeed today they have occupied us, as Rome used to occupy Illyria. But I, during my conferences, will repeat to the Italians without hesitation, that indeed Rome once had a great name, but the Illyrian legions and the great Illyrian emperors were the ones who had the fate of Rome in their hands. I also made another promise, that those conferences will be held for six months, as required by the regulations, I will immediately request to come to Albania”.

About this moment in Fishta’s life, a lot has been written and spoken, not only by his enemies, who here found the opportunity to speculate and throw a lot of mud on his patriotic figure, but also by some others, who they announced him as a patriot and national poet. In the Canon of Lekë Dukagjin, which expresses the high, inherited wisdom of our people, this principle was said: “Put you at my feet”, or, “Put yourself at my feet”. I am repeating this expression for all those who love the truth and not for the painters, who change the colors as they like.

Therefore, I felt it was a historical and moral duty to tell this episode of our internal life, of the Franciscan community, although I foresee that this episode will be given different interpretations, both for and against Fishta. A few weeks after Fishta left for Italy, here in Albania, the fascist authorities started a war against the Albanian Franciscans, because they did not accept raising the flag with the lictor’s flags in the church bell tower, nor in the school program, Fascist teaching and education. The Minister of Education himself came to the Franciscan schools, but here he was received coldly by the teaching staff, as well as by the students.

Then, due to the intrigues of the fascists, he was imprisoned in Shkodër and then exiled to Italy, prof. Athanas Gegajn, the Franciscan schools were closed, the Franciscan musical bands were confiscated, the “Antonjane” Society was closed, and its director, Father Lekë Luli, fled to Yugoslavia. After a few years, the same way of escape, Dr. Prof. Father Gjon Shllaku, director of “Hyllit te Drita”. Meanwhile, Father Anton Harapi and the Provincial of the Franciscans, Father Čiprjan Nika, were called to Italy, and were kept there as hostages, under different pretexts. During this time, Fishta tried with all his authority to become the master of the Franciscan brothers and to revive the works, which he himself had founded, such as the “Illyricum” Lyceum.

We must note here that the key to Italian policy for Albania at that time was Mr. Salvatore Meloni, secretary general of the Luotenency, ex-consul of Italy in the city of Shkodra, long-time friend of the Franciscans and of Fishta. Another episode is happening here, which was shown to me by one of the cages of the Italian consulate in Shkodër.

Fishta had come to the east country to spend time, mainly to get away from the constant intrigues of political and commercial life. He felt very tired, to say the least; he was disappointed in the fortunes of his homeland. This was also known to his closest collaborators, such as Monsignor Luigj Bumçi, Monsignor Vinçenc Prendushi, who at that time was in Nënshat and week after week, came and spent a day and a night with him; while Monsignor Luigj Bumçi, who lived in Kallmet, used to come to the assembly to eat and return home to eat after lunch. Father Pali came less often, every two or three weeks, because he was a short distance away.

In the presence of these friends, it was clear that Fishta felt relaxed. With Pater Pal, they almost always had serious conversations, while with Bumçi, it was completely different. They both competed with each other for anecdotes, expressions and humorous comparisons. Anyone who was lucky enough to be in the presence of these conversations could not dream of a greater joy. Although this competition took place between two colossuses of humor and satire, after all, Fishta stood out for that incomparable elegance, which avoided any banality and magnetized the whole environment. I want to note here that Fishta, in his speech, was never so harsh and rude, against his friends, as is presented in the written satires.

He spent almost the whole summer in Troshan, and when I moved from there to Shkodër on September 15, I left him there. But, towards the end of October, we received the news that Fishta was very ill. Dr. Prela was immediately sent to Fretni to visit him, and the Academy of Italy was informed, which after a few days, sent two doctors. He proposed to Fishta to leave Troshan and go to Italy for treatment, but he refused. During the next month, there was improvement, so much so that he seemed to be cured. It is the beginning of December, the first snow fell. Fishta goes to the window, look at that white hair, which without stopping comes down from the sky, with endless movements, as if they were living heavenly beings who come down as quickly, as quietly, to say something to humanity.

We do not know what phenomena and other thoughts are captured in the imagination of the poet, who, like a small child, forgets that snow is cold. The next day, Fishta feels bad. After three days, when the doctors go from Shkodra to visit him, they find him in an alarming condition, with bilateral pneumonia, and order him to be treated immediately, in the Shkodra hospital. It seemed that the cures and medicines brought him benefit and improvement, but after a while, it became clear that with the tools that were available at that time, there was no escape, therefore many of his friends and personalities of the time tried to help him one more time, as long as he was alive.

The winter of 1940 was very difficult and harsh here. The funeral that took place in Shkodër was magnificent, long, but also very difficult, because the streets of the city were covered with almost a knee of snow and it continued to rain. After the funeral, the requiem mass was given by the Archbishop of Shkodra, Monsignor Gaspë Thaçi, who also delivered the last funeral speech. Among other things, in that speech, he said: “A few days ago, I was in the hospital to see Father Fishta, who by now had realized that these were the last meetings of his life and he told me: He is not coming It’s a pity that I’m leaving, because we’re all going there, but it’s bothering me, because I’ve given up my life to see a free Albania, and today, I’m leaving it to be trampled by foreign armies” . When the orator said these words, the public witness in the presence of the highest authorities of fascism in Albania, the people as they are, let out a cry, a noise of fear and admiration. Radio-Tirana specialists at that time recorded the speech and the entire funeral. I believe that if those tablets are saved in the archive, the speech can also be found.

After the requiem mass, when the people left, only us Franciscans remained in the church, with Fishta’s body. The burial was supposed to take place inside the church, in one of its chapels, but we were all very tired from the long funeral, with such a difficult time, then we were told to relax a little, change the wet clothes, and to warm up, it was left for the burial to be done after dinner. But since there was no heating between the rooms, most of the guests had fallen asleep. The Superior of the Franciscan Assembly of Gjujadoli at that time was Father Frano Kiri, who took some of the younger friars, as well as some of us students, to open the grave.

The chapel of the Franciscan Church, where he would be buried, was already marked in advance: the one on the left, just as he entered the church. It was said that the Italian Academy would work on the monumental tomb. When the work tools, picks and shovels were gathered, many discussions were held in that chapel, where the grave should be opened, the pit, for the provisional placement of the body. It was considered reasonable, that in order to leave a free path for the works, the pit should not be opened in the area of the chapel, where it meets both with reasoning and with aesthetics, but it was opened at the right end, at the entrance of the chapel. The great body of Fishta was placed there, in the presence of more or less people, of which, as far as I know, Father Leon Kabashi and I were too many.

For aesthetic reasons, we did not place the marble slab on the pit where we buried him, but in the area of the chapel, and the actual place of burial, we covered it with the usual floor tiles. So that marble slab, with the name of Pater Gjergj Fishta, on which wreaths of dedication and glory were once placed, and later became the object of rape, it did not contain the bones of the poet. Did you ever discover Fishta’s true grave, and were his remains thrown into the river? I can’t say anything for sure. There, after the closing of the churches, in 1967, there were many perverting works of that architecture. For this, I believe that the most accurate explanations can be given by the workers who participated in those works, mainly the implementing engineer, as well as the then chairman of the Executive Committee of Shkodra.

I think it would be good for a special commission to be created for this occasion, with the support of the Government, which will take the exhumation of Fishta’s remains to the end, at least for a historical explanation. Personally, I am against the cult of all mortals, however genius they may be; however, I am all the more against all the vandalism that has left the Albanian people and our country to disappear, without any historical relics, without any artistic monuments and without historical documents, to show future generations the culture we had , but everyone, who has a little power in his hand, thinks to start from the beginning and, this is how we have always remained throughout the centuries, many of us in the country. Memorie.al