By Reshat KRIPA

Part one

Memorie.al / Arbër stood in his corner in the hall, waiting for the arrival of the plane that would take him to another world, and he meditated. He meditated and dreamed about the path full of stinging nettles and thorns through which his life had passed. He recalled the worries that had accompanied him for years. He had many passions. He wanted to become a lawyer, journalist, doctor, engineer, artist, writer, or whatever else might be possible. But fate had condemned him not to reach any of his dreamed-of peaks. He encountered disappointment at every step of his life.

Starting from the first grade of elementary school, the figure of this individual had begun to shine, and this accompanied him throughout his life’s journey. Despite the intrigues and pressures put upon him, he always pushed forward on the difficult path. He finished high school with the highest results achievable. The road higher up was closed to him.

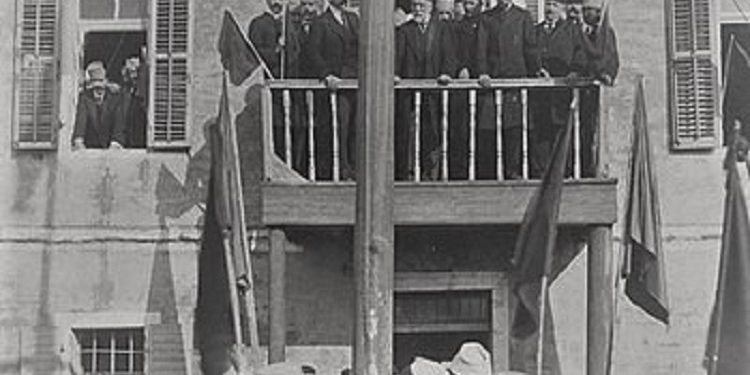

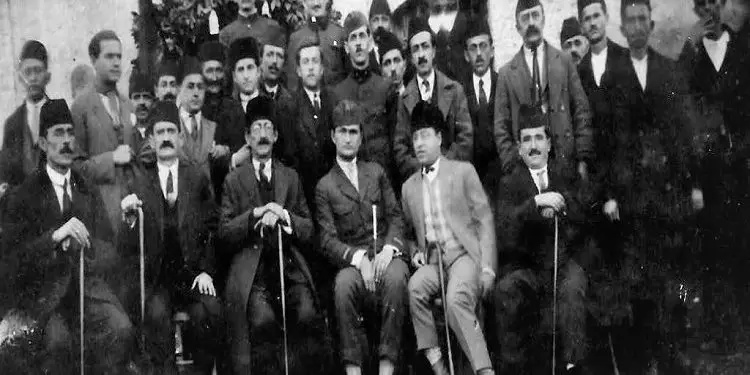

His mind flew back to the distant past. He pictured his grandfather, Luan Dauti, who had been one of the participants in the great movement that was crowned with the victory of Independence in 1912. He pictured November 28th, when his grandfather had been a participant in the Great Historic Assembly, alongside other distinguished men of the nation. He also recalled his grandfather’s participation in the Congress of Lushnjë and the 1920 war that threw the Italians into the sea.

These images appeared, and he felt pain when he saw that nowhere was his grandfather’s name found, nor his activity reflected. He had inquired several times, even at state institutions, but everywhere he had received the same answer: “He was not a participant.” Such a thing angered him, as many old men, his grandfather’s peers who knew him well, had spoken to him about his grandfather’s activities. One day he went to the Independence Museum House.

He immersed himself in the annals of the country’s biggest event, November 28, 1912. He looked at the photographs of that historic event. He stopped at one. It was a group of well-known personalities of that period. But his grandfather was missing, and surprisingly, he had seen this photograph with all the participants, including his grandfather, a copy of which his mother still kept in her chest. He noticed that other figures who had been protagonists of the event were also missing. He realized that the figures had been retouched, replaced by others whose names had never even been heard. He noticed the same retouches in the City Historical Museum – the same retouches concerning the Congress of Lushnjë and the Vlora War. His grandfather was absent.

Such a thing surprised him. Why were these characters erased from the face of history? He went home and sat down to talk with his mother. She told him: “Son, we live in a strange world. This is today’s Albania. Be careful, son. Get rid of these thoughts. Let time resolve them. I am sure that one day they will come to light, and you will live to see that day. For now, keep silent.” And Arbër kept silent.

These images appeared in his imagination. The path of his life appeared before him. The life of the family came before his eyes. In particular, he recalled the death of his maternal grandmother, who lived with them, when barely fifteen to twenty people – only the closest relatives – gathered to accompany her to her final resting place…! Friends and comrades who had accompanied him throughout his life appeared. He recalled those who, despite the living conditions, had helped him survive, but he also remembered those who, with envy and egoism, tried by all means to hinder him on the path he was following, and these were the majority who feared him like the devil fears incense.

At that moment, he remembered a fragment from Victor Hugo’s novel, The Man Who Laughs: “Sometimes, when severe trials fall upon a child’s head from the tenderest age, a kind of scale, a terrifying scale, is born in the hidden corners of his soul, with which he weighs the affairs of this world!” Feeling innocent, he submitted to fate without a sound. He did not complain at all. He who has nothing to reproach himself for does not reproach others.

He too, like the hero of the novel, had gone through very severe trials, but with his character, he had managed to face them and emerge honorably from all that turmoil. Life had taught him how to be human, how to react when bitter surprises arose, and how to maintain his integrity intact. For all this, he felt proud of everything he had done. These came before his eyes as he waited at the capital’s airport for the arrival of the plane that would separate him from his homeland. Why was he leaving now that the totalitarian system had finally been overthrown? This question tormented him excessively. He faced a dilemma: Was he acting correctly?

Arbër had not had the fortune to know his father, Sokol. He was born after his father had flown to the eternal world. Sokol was a well-known man throughout the region, a distinguished lawyer. He had graduated from the law faculty at the Sorbonne University in Paris in the last year of the Monarchy.

During World War II, he had sided with the nationalist forces, being one of its well-known figures. When the course of the war highlighted the victory of the communist forces, he did not attempt to abandon the homeland, as he never thought that with the end of the war, they would arrest him and massacre him with terrible tortures that would take his life. At that time, he was only thirty years old. It was the end of the second post-war year.

Arbër was born three months after his father had passed away. Thus, he was raised by his mother, Afërdita. She had graduated from the “Nana Skanderbeg” Pedagogical Institute, which before the war was called “Queen Mother.” Her results were excellent, but the paths to pursue higher education were closed. The mentality that existed in Albania at that time was such that very few women could study abroad.

While still in her final year of high school, she had met Sokol, with whom she had fallen in love, and after the end of the war, they had married. At that time, she practiced the profession of literature teacher at the city’s high school. The arrest of her husband and his demise in the prison cells changed the course of her life. It was the end of August when she reported to start work after the summer holidays. She was informed that she could not start, as she was unsuitable for the education of the new generation.

“Mom, when will we see dad?” – Little Arbër would ask his mother. He was only three years old and could not understand why his friends had both parents and he did not. Afërdita did not know how to answer him. She could not tell him that his father had closed his eyes in the darkness of the cell, and even if she did, how could his infant mind grasp what a cell and torture were. She had decided to tell him only when he reached maturity.

“Your dad has flown to the sky,” she told him, and showed him a photograph where he was cheering with his hands up during a popular demonstration. “One day we will go there too and live together.” “Hooray!” the boy shouted joyfully. “Hooray!” the mother shouted back and took her son in her arms, hugging him tightly. Hot tears began to stream from her eyes.

Before her eyes appeared Sokol, speaking to her with great passion about the idea he had embraced and its program – a democratic program, identical to that of many other European countries. He had even brought her a copy of that program, compiled by one of the most brilliant figures of Albanian nationalism. She still kept this copy.

She had read it several times and continued to read it always. She remembered when he spoke about this program, comparing it with the principles of the French Revolution that he had learned at the Sorbonne University. Afërdita read and asked: “Why did they kill him? What crime had he committed? Is it a crime to embrace such European democratic principles?”

She was unable to answer these questions, as this was the time when the clash between the forces operating in the country had reached its peak. It was the time when the “winners,” to maintain power, were ready to devour not only their political opponents but also each other, disregarding the country’s traditions and even family ties. It was the time when members of the same family spied on each other. Unprecedented terror was waged against those who thought differently. At that moment, she recalled the verses of a famous poet from her region:

“The son catches the father, the father catches the son, to seize him and expel him,

To roast him alive on a spit, to cut his flesh with scissors!”

To survive, Afërdita was forced to sell some of the valuable items she had in the family, as well as use aid sent by her relatives from another city. This is how she managed to face life with her son. But one day, those ran out.

They had been evicted from their beautiful two-story villa, confined to a single room on the outskirts of the city. She thought of approaching the Chairman of the Executive Committee of the city. She requested a meeting, and he received her. She presented her situation. She showed him her high school diploma. She also told him about her husband who had died in prison.

“This is my situation,” she told him. “If you do not give me work, then take me too and lock me up where you locked my husband, and let my child die out.”

The Chairman listened and remained silent for a few moments. He did not know how to answer. He recalled the directive that came from above, according to which, individuals from the overthrown classes should never be allowed to work in education. Such a thing was impossible. He wrote something on a piece of paper and handed it to her, saying:

“Go down to the Labor Office.”

“Thank you!” Afërdita replied and left. She opened the letter and read:

“Place her in a job!”

At the Labor Office, the manager received her. He was a person brought down from the remotest corner of the district, who had never seen the city with his own eyes. Participation in the ranks of the “winners,” where he had even completed an anti-illiteracy course, had raised him to the rank he enjoyed.

“Tell us a bit about your autobiography, comrade!” the manager said. Afërdita initially remained silent. She did not know how to proceed. Finally, she decided and told him the truth. He smiled bitterly and said: “You are a bourgeois class, madam! You hold your head high. Nevertheless, the people’s power does not let people starve to death like the bourgeois state. You will go and work as a cleaner at the ‘Martyrs of Liberty’ high school.”

Afërdita froze. She did not expect such a thing. She had once been a literature professor at that school, which previously bore the name of a high-ranking language personality, but who, unfortunately, had been connected to the Nationalist Movement during the War and, after its conclusion, had also been executed as an enemy of the people.

The manager completed the work assignment letter and handed it to Afërdita; “Take it and start work.” Afërdita hesitated. “You don’t like it,” the office manager continued. “Naturally, you bourgeois people do not easily lower your heads, but today these things don’t suit you. Do you want to take the work assignment sheet, or not?”

His arrogance surprised her. She thought for a few moments. Finally, she took the sheet and left. The next day, she reported to the school’s principal’s office. The principal was a former colleague of hers, Andrea. When he read the work assignment sheet, he froze. Silence reigned for several full minutes. Finally, he spoke: “Leave and come back in a few days.”

“Don’t bother, it’s useless,” Afërdita told him, understanding that his intention was to talk somewhere higher up to place her in the position of a teacher. “Leave, and when you return, we will discuss it,” the principal repeated. He was convinced that something thoughtless must have been done by an individual who did not know her personality. He thought that with his intervention, he would correct this mistake. Afërdita left, but deep in her consciousness, she thought that Andrea’s attempt would be futile.

She returned three days later. She found the principal in an indefinite state. With his head bowed and a trembling voice that barely came out, he told her: “Forgive me!”

“It’s nothing, thank you for everything!” she replied.

On the first day she reported, her former students surrounded her. “Teacher, are you back?” they shouted happily. Afërdita did not answer them. She greeted them and headed to the Principal’s Office. The principal lowered his head as soon as he saw her and did not speak.

“Have you come?” he finally said. “Yes,” she spoke in a calm voice. He continued to be silent. Andrea had completed his higher education in Vienna. During the war, his family had joined the National Liberation Movement. His father, Doctor Robert, had been a doctor in a partisan hospital. He was a well-known figure throughout the region. He had specialized as a surgeon. At one time, during the time of the Monarchy, he had worked as an advisor in an Italian medical team that had come to set up a health center in the city.

He had earned a good name in his specialty. Many citizens had been saved from death thanks to him. In particular, he never hesitated to go even when they called him to treat someone wounded during the war. Wherever he was, he took his bag with the necessary tools and left immediately. Thus, he had earned the sympathy of the majority of citizens.

Andrea had collaborated with the city’s guerrilla units. So, he was appointed principal of the high school. But he had a different concept than the other leaders of various institutions. He had joined the Movement because he was convinced that it was the most realistic force to build a democratic Albania. The post-war reality had disappointed him to some extent, but he believed that this was due to the incompetence of some leaders and that it would be rectified over the years.

He was married to Elvira, also a teacher, a close friend of Afërdita’s. They had two children from the marriage, a daughter, Vojsava, and a son, Petrit, the same age as Arbër. Now he stood with his head bowed and did not know how to respond. He knew her abilities well, so he could not understand why they acted this way towards her. He had talked with some of the personalities dealing with the city’s cadres, but he had not found support in any of them. In fact, one of them had told him in a low voice: “Why are you putting yourself into these waters, do you want to drown too?” So, he kept silent and did not pursue it further. But internally, his conscience tormented him.

“Andrea…” Afërdita woke him from the thoughts he was immersed in. He interrupted her by raising the palm of his hand, wanting her to be silent. He got up and motioned for her to follow him. They headed towards the school bathrooms. There, he showed her a bucket, a broom, and a stick attached to a board, around which some rags were wrapped, which served to wash the floors.

“These are your work tools,” he told her with a voice that barely came out of his mouth, and left. Afërdita did not even have time to thank him. Thus, she began her new job. Initially, she cleaned when the students were on break from classes or when they left for home. She was ashamed to come before their eyes. Even the students looked at her with pity. They did not understand how their former teacher was now transformed into a simple cleaner. Nevertheless, whenever they met her, they greeted her: “Good morning, Teacher.”

The only one who tried not to acknowledge her, looking at her askance, was Demir, a teacher who held the position of party secretary for the school. He treated her as a class enemy. Her pride with which she faced him infuriated him even more. He often intentionally made her clean a second time, supposedly because she had not done it well, yet she continued her work with her head held high.

“Why don’t you answer, are you perhaps mute?” he would shout at her. She would look him in the eye and leave for work without speaking. Silence was her weapon in this duel. This infuriated the secretary even more. Memorie.al