By Namik Mehmeti

-In homage to the former political prisoner, the passionate teacher from Mirdita, who recently passed away-

Memorie.al / Recently, after learning the sad news of Gjeto Vocaj’s passing, I was reminded of an event when I was working as a teacher in Rrëshen of Mirdita. This was after reading an article in the newspaper “Mësuesi,” published by the Ministry of Education in the 1960s, written precisely by teacher Gjeto Vocaj about a young boy, a born phenomenon in mathematics. The six-year-old Nika, in the depths of the Dukagjin mountains, in Palaj-Shosh, had astonished the 22-year-old teacher with his mathematical abilities. Without any books or notebooks, while seated at his school desk, he could perform multiplications with double or triple digits as well as other operations like addition, subtraction, and division.

It did not take long for the echo of this article to travel from the Northern Alps to Shkodër and Tirana. The name of Nik Marashi, the six-year-old boy, would be mentioned in every school in Albania as a mystical discovery.

Years passed, and the names of teacher Gjeto Vocaj and his student Nik Marashi never left my mind, as I wrote about the education of the Mirditan teacher. During a meeting at the editorial office, one of the editors presented me with a page from the newspaper, asking me, “Do you know this teacher, being from Shkodër?” Naturally, I hesitated.

We also discussed this article in the Pedagogical Council, where once I was interrupted from the conversation by Mr. Gega, a respected figure among colleagues, not only in Rrëshen but throughout the Mirdita region.

Mr. Gega, the head of the high school and seven-year school dormitory, was for us newcomers like a compass of orientation, and he didn’t hesitate to inform us about the backroom dealings rumored in the offices of the Party committees, either Executive or other institutions of the dictatorship.

“I know the lineage of this Mirdita teacher. They are from the Gjonmarkaj family, and his maternal grandfather was executed!”

This was enough for the names of teacher Gjeto Vocaj and his student Nika to remain firmly in memory until the moment of meeting him. With the collapse of the communist dictatorship and the establishment of democratic pluralism, in the neighborhoods of Shkodër city, as in all of Albania, the functioning of pluralistic people’s councils began, subordinate to the Municipality. Someone had also put my name forward as a representative of the anti-communist right in this first pluralist council after nearly half a century.

More than half of these councilors, who were from the left side, naturally communists, I recognized by face, but in my side, one person caught my attention, someone I had not noticed before, in the main neighborhood of the city, called “Vasil Shanto”! When it came to the presentation and proposals for the new leadership, someone proposed the name Gjeto Vocaj for council secretary.

I, for the moment, raised my hand in favor. The man next to me stood up and thanked everyone for the vote. “Gjeto, am I mistaken, the teacher of Nika from Dukagjin?” I asked without letting him take a seat.

“Yes, that’s me,” he replied, his voice revealing more than modesty; it suggested that this name had a backstory. Hearing it from his mouth, I thought the scenario for a film would be a priceless gift for any director.

Thus, the phenomenon Nika, who had “escaped” from the Dukagjin Mountains to the offices of the Central Committee of the PPSH, right to the office of the communist dictator Enver Hoxha, was privy to this privilege of Gjeto Vocaj — to converse with “the One” of the country, precisely in his fearsome office. It was considered a fateful omen for the future of the 22-year-old boy.

“This discovery must be kept secret,” Enver Hoxha had said in the presence of Ramiz Alia, and two guests; Prof. Bedri Dedja and teacher Gjeto. “The internal and external enemies might react to eliminate Nika!”

After learning everything about this adventure involving these two characters, which was thought to have a journey like that of a “flying carpet,” the second part of this adventure was surprisingly heard with many sighs and interruptions during the conversation.

“Those who learned about this ‘success’ congratulated me, while I secretly suffered, sometimes saying; why did I enter this path? Not many people, especially here in Shkodër, knew that my maternal grandfather had been executed by the State Security Pursuit Forces as a nationalist and anti-communist.

But I was convinced that the Security organs, the Internal Affairs Branch, had registered such a fact. And secondly, the silence and change in the dictator’s expression when he asked me; Nika, do you know the members of the Politburo? And my ‘no’ changed the atmosphere of the meeting. He would undoubtedly become interested in the biography of this teacher, who did not teach his students who the Party leadership was.

And where would Nika learn about them, in that darkness, without school, without books or notebooks, without newspapers or cinema, who the members of the Politburo were?! And this ‘no’ set the State Security in motion, and as I later learned, one of the deputy heads of the Internal Affairs Department had prepared my file, accusing me of agitation and propaganda and failure to denounce a comrade who had fled to Yugoslavia.

After six months of investigation in 1979, I was sentenced to seven years in prison, which I served in Spaç and Ballsh. After my release, I was interned for five years in the village of Karmë, Vau-Dejës, while my wife, Lili, with our two children and my elderly father, had been interned in Pistull, Zadrimë.”

This was, more or less, what Gjeto told me, and I promised him that I would write an article about this event. The local newspaper “Shkodra,” although it was the organ of the District Party Committee, did not hesitate to give a space on its pages. The title; “Meet Nika from Dukagjin,” piqued the curiosity of many citizens who wanted to learn who teacher Gjeto Vocaj was.

I felt pleased when I introduced him to the residents of the neighborhood, who came to obtain a certificate for food rations. Those who never thought that one day they would extend their hand to a former political prisoner would receive the desired certificate from Gjeto without hesitation, accompanied by a smile.

During the time we worked together in that pluralist council while maintaining friendly relations, I got to know a quiet intellectual, a noble man. In our first conversation, I realized that Gjeto had the formation of a teacher with a broad outlook, a regular reader of historical and artistic books published with the advent of Democracy, including foreign languages such as Italian and French.

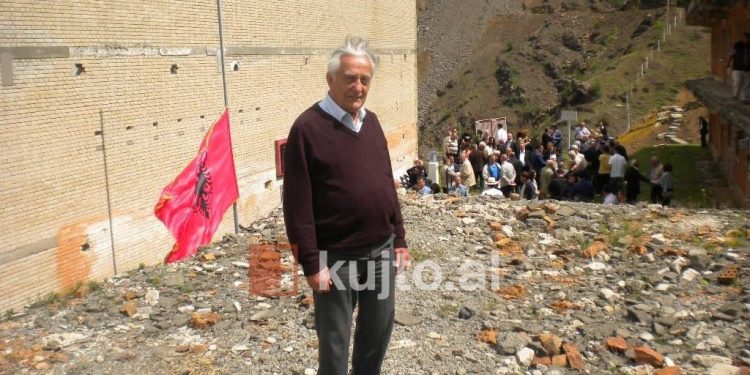

In fact, he had mastered the latter after being released from prison in 1983, working on the restoration of the “Rozafa” Castle, where he met a French couple participating in the restoration and established correspondence with them, gifting them various literature. The days he spent in France, invited by this couple, gave him energy and optimism to leave behind the sufferings and sacrifices but without forgetting them.

In the pluralist council of our neighborhood, Gjeto helped not only his fellow sufferers from the Association of Former Political Prisoners and Persecuted Individuals, and former property owners but also poor families. Gjeto assisted school students with free courses to learn Italian and French.

As I write these lines in gratitude for the late Gjeto Vocaj, my son here in Florence remembers arriving in Italy for secondary school, finding support from Gjeto in communications with the Italian embassy and a family in Jesi that provided a guarantee.

We met Gjeto last autumn, somewhere in front of “Kafes së Madhe,” in what was once the “Lulishtja Popullore,” always in the company of the former mayor of Shkodër, the esteemed intellectual, Mr. Filip Guraziu. We reminisced about many days of our family friendship, where his honored wife Lili would offer us glasses of raki and snacks with great warmth.

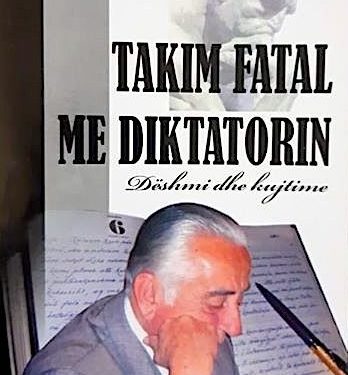

With the fall of the dictatorship, Gjeto did not seek privileges as a former political prisoner; he did not “betray” his beloved profession as a teacher but became a strong voice in exposing the Enverian communist dictatorship, an eyewitness to the sufferings of former political prisoners in prisons and forced labor camps, as well as the hardships faced by rural communities to secure their daily bread.

Just as always, calm and communicative, but the sufferings in the prisons of the dictatorship had begun to affect his health, he did not shy away from evil, even after suffering a family tragedy with the murder of his son, Edit, a 28-year-old, who was killed while defending their family and property! /Memorie.al