From the story of Visar Zhiti – published in his books and in many newspapers in Tirana and in the diaspora.

Today, on His birthday, on his 100th birthday…

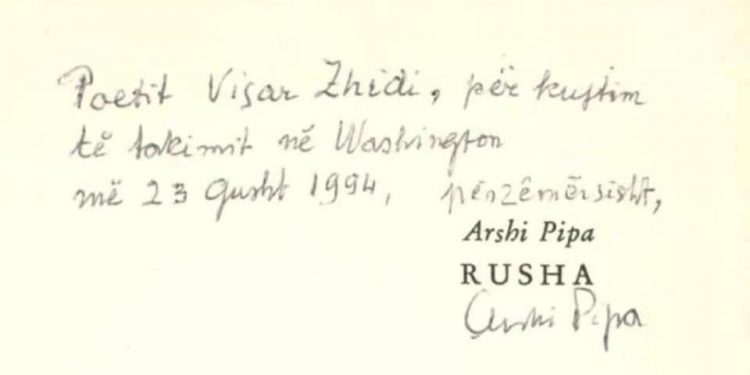

… I was feeling the urge to browse Arshi Pipë’s “Prison Book”, I do not know why, the day itself seemed to love him, or because he had once given it to me in Washington, or from the absurd letter that a former American congressman, Arbëresh emigrant, but that they must have known each other, he sent it from New York to the mayor in Tepelena, where the infamous internment camp, nicknamed “Albanian Auschwitz”, was commemorated, while Arshi Pipë’s autograph seemed to order me…

… The message that comes to us from him, the strict resistance fighter, former political prisoner, brave fugitive and anti-communist immigrant, essayist, literary critic, translator, philosopher, who wrote not only in Albanian, but also in English and French , the emblematic above Arshi Pipa., is an order.

Surprisingly he is not being reminded so much, not to mention anything else. Why this silence, or have they not found anything in the State Security file to make a fuss about?

I am flipping through my notes from the memorable meeting with the professor.

BOOKS AND ASHS OF ARSHI PIPË:

… Phoned that he was waiting for us at his home that morning in Washington, at 10:00. Since we had some time, we decided to enter the nearby bookstore and then continue a short walk. Washington, I was thinking, is a city with a classic European physiognomy: there are no skyscrapers, as was the imagination of Albanians who did not come to America, but you see shopping everywhere, clean streets and white tranquility. Perhaps this feeling is given by the White House, the Capitol, the famous Library of Congress, all white. A capital that has far more trees than… police. And how many squirrels! Squirrel citizens!…

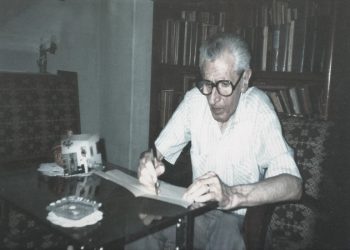

They stopped, looked us in the eye, were not afraid of people, and even waited for you to give them something to eat; biscuits, sold especially in shops, approached, wagged their big and beautiful tails like silver, went out and on the road, ran under stopped cars, wandered, turned back, rushed up the trees, god knows what they were looking for. We too were in a hurry now. We did not want to be late to the house of Professor Arshi Pipë, under a sun that seemed white to me and him. After our gentle knocks, the door was opened to us by the professor’s older sister, while at the top of the wooden stairs upstairs, on the second floor, the professor himself was waiting for us, standing, tall and thin, straight, with his hair white, “Washington”, but also as the distant snow of the homeland, which never melts. Surprisingly black eyebrows, as it seemed a mixed mark that did not detach for life from his noblely long face. I could not determine whether they emphasized or neutralized the somewhat skeptical look of that face, whether they gave it more youth, along with a wise pessimism, but still with a tireless cordiality.

“I know your name,” he told me, as we sat in the simple armchairs, “you are a young poet and you have been in prison.” To the latter I attach importance… to the writer, – he added. I immediately told him what I knew about his “Prison Book”, published in 1959 in Rome, what I had heard and how I had finally read it. When the author escaped, it was precisely those hellish sonnets that had made the opposite path to the author, just as dangerous, if not more so, had been secretly introduced into the homeland, through barbed wire. I had made efforts to publish a cycle of them in our new opposition press. I remembered the sonnet about a man lying in a vig, which death turned into a rag coffin…

“It happened to me… with my father,” the professor explained, “he died on the way to prison.” – Even his voice seemed to whiten, the same, with a little hoarseness that he blamed the tortures, – that’s why it turns out to me. With cooling. Cement glass. “In our tribe,” said the professor, “we have no such voice.” Then we took him to the hospital, – he laughs ironically, but his voice broke. Who was taken to the hospital, the dead father or the voice? There is no such voice in the tribe…

“We know this voice,” I intervened, “that the dictatorship could not break.” Neither freedom nor well-being and success. And I showed him his books on the table, to which he was throwing autographs, he was giving them to me. My wife suddenly shot the camera at us. She must have been fascinated by her grandfather, who was also imprisoned in the Maliqi swamp, here, where the Professor was, they must have known… on the mud, where often, the police fell, they falling from great torment and great hunger, he trampled them with his feet. They rode with boots on the back of the convicted man until they plunged him deeper and deeper, into the endless sludge, into the swamp of death. Yes, her grandfather survived, even when the police threw a bomb and another man jumped, because he knew a piece of bread and wanted to cut it, but it was torn to pieces. And again they would arrest Dane Zdrava, always, because he had been the first businessman, he had brought the first cinema in his city, in Berat, yes, he had an academy in Italy, he brought power plants, combine harvesters in the lands of his and forgave furs or made all his friends’ daughters and as he was taken out of the house handcuffed, he hugs for the last time his little granddaughter, who has just returned from school… and she now photographs her grandfather’s sufferer.

They will surely have known each other, they have talked, even without knowing who they are, there, in the swamp of death, they have hoped. The author of the prison mud sonnets was lucky then, she asked for luck, she did it herself and now, now, she talks to her husband, who is also full of prison poetry, all the darkness of hell.

“I am a bourgeois family,” Professor Pipa continued, “not in the sense used by the communists.” Everyone in my family has been brought to justice: judges and lawyers were there and I had to do proletarian work, harder than proletarians. Yes, I care about the prison, I call it a university…

– zi black, – I added. Then the Professor began to talk about François Vignon, the rebellious poet, the vagabond, the prisoner, the hanged man, but who escaped the rope… (Ah, our Avzi Nela, he could not escape… the communist dictatorship was worse than the Middle Ages.) I love Vijon, – it seemed to me as if the professor had been kidnapped, but still calm, with the mysterious calm he finds in a temple. With Vijon it is seen that life is another thing and poetry is another. Kadare’s creativity is like that… Even “Wedding” is a dissident novel…, he said and was silent for a long time. I did not want to interfere. I just wanted to hear it. As it was said, Arshi Pipa was seen as a staunch, authoritarian, “greatly ruthless” man with the dictatorship he challenged, not only as a political exile, but as a poet and thinker, above all. The professor would unequivocally affirm that our Homeland is better than ever, with all the great reserves it may have. The bunker dictatorship was torn apart by the fragility of democracy. After all, democracy is also critical to improving oneself.

And he wanted to show me his translations of the great classics, Dante and Petrarca, Goethe… French, Russian and Romanian. – I translated them, – said Professor Pipa – some in Tosk and some in Geg. I give them, but do not publish them. I congratulate the Kosovar publications that managed to be written in the literary language, even though they were for the use of two dialects, I too. “They are wealth,” he insisted. “Even the common literary language is!” I replied. “He came quickly,” he said again. As we drank coffee, I got up to look at the strange bookshelves. Long and empty! Bo-o (h) -osh… Just a few dictionaries, the latest manuscripts in a corner, the ksomblat of other books, the works of his great friend, the other fugitive, the poet Martin Camaj. So! And pain like wood. What was dead there? Here are some enlarged photocopies of cigarette papers, where he once wrote prison poems. With them he had escaped… How the shelves looked like, dramatically empty, like coffins. Set-set. Where are the books, I wanted to shout inside. I asked not to look out the window at the magnificent building of the Library of Congress, to facilitate my breathing somewhat. The professor had donated his entire library, the books of his whole life, to the library of the city of Shkodra. He also felt like a citizen of Shkodra, even though he was originally from Libohov. A high gesture of donating books, he gave him alive, without leaving it as a task to the will. Why? I thought the way back. Where did he find the power to share with his own books, the purpose of his life?

“I’m dealing with philosophy now,” he told me when I asked him what he was writing. So he was daring to coexist with his own death, with the inevitable escape to other lives, to the heavens. Was it a philosophical challenge raised above the ordinary, the defeat of death itself, the triumph of eternity? And just as I was shocked to see that wooden emptiness, the library of invisible books, the exile, I heard his voice criticizing an orthodox seminar in America of the Greek lobby. Then we talked about the Balkan epic. “There is a whim and shame,” he said, “to steal other people’s stories.” We extort lands and legends and disturb the dead. We politicize friendships, but also diseases. Our epic, he said suddenly. Not that it is not beautiful, on the contrary, it is beautiful, magnificent, but because the characteristic for our verses is traditionally the use of the four-syllable, while the epic has eleven syllables. That the South Slavs have. So what can we say? The Yugoslav writer, Ivo Andriq, found an opportunity and I was telling him, he says that Gjergj Elez Alia’s song is Albanian. Yes, she is Albanian, Arshi Pipa affirmed with a cold curiosity. Where would I go out? But is it eleven syllables “Gjergj Elez Alia?”, I almost shouted amicably. Yes, he said again and was silent. Bookcases were flashing in their eyes, their primitive memory. I was looking at the dedications in the works he donated to me: “… the young poet and fellow prisoner…”, “… this book written and completed in exile”, “in memory of the meeting in Washington on August 23, 1994, cordially…” and had signed below the name printed on the frontispiece: “Arshi Pipa”, in small letters. It became like worries and emptiness inside my chest like the shelves. I definitely wanted to remember the squirrels and I stretched out my hand in the air, as if I was touching them. I would meet Arshi Pipë and once again in Tirana, he gave an excellent lecture on Martin Camaj’s poetry. With his poetry begins peace in Albanian poetry, said the professor. Later came the mortal news that Arshi Pipa had passed away and had demanded that his ashes be distributed… over the homeland. In the Adriatic Sea. Grace has within it renewal, it is not forgetfulness, it is first purifying and nourishing the earth and time. Arshi Pipë’s gracious work is already the wealth of our life, of endurance and culture as a whole, illuminating phosphorus in the collective memory, irreplaceable value, except by itself. Let us throw that ashes on Tepelena, on Spaç and Qafë Bari, Burrel and Lushnjë… on our memory and our consciences!

CONVERSATIONS OF PRISONERS

FOR ARSHI PIP P:

FROM THE BOOK “THE WAYS OF HELL”,

burgology by Visar ZHITI

Mak Maks Velo was telling me with rage and art that one day, when it happened at the National Library in Tirana, a package came with a gray book, with a strong lid. Arshi Pipa. Prison Books. Poetry. Published in Rome. English. I wanted to browse it, to read only one poem. Only one. A string. Standing there. I was not even allowed to open it. It was prohibited. He had come especially for the president of the Writers’ League, Dhimitër Shuteriqi, the masquerade, the curse, but he would be included in the black fund of the Library. Arshi Pipa is a fugitive. He was in prison, in the Vloçisht swamp. Stayed alive. He was released from Burrell Prison. He is now a university professor in America. The prisoners say that he wrote a screenplay for the movie “Cherry”. Jo roman? And it was realized by Hollywood. It seems incredible. The horrors of our prisons are narrated, especially that of Burrell. How they killed the prisoners on the last day, that of their release, and buried them in that cherry tree. There were those who fainted as they watched the film in the West, continued to show prisoners, scream in cinemas, an ambulance arrived, one pulled out a revolver and shot at the screen to repel an Albanian officer who was tearing it to pieces. his own prisoner. We do not know anything, said those who had come from abroad such as the Swedes, the American Agron, the North French, the Germans, the Greeks… However, we said, even if it is not true, we, the prisoners, feel the need for protection, to a great appeal against the oppression that is done to us, the most terrible indifference and the most terrible forgetfulness. We need a work of art. Someone is doing it or should do it. We have now chosen the name of a co-sufferer, Professor Arshi Pipë, he carries this honor, we are trusting him. Others inside, the more glory they receive, the more they have cheated. It is very likely that it is all our creation, collectively. Cherry is indeed, but we do not know if it has been introduced into literature? We comfort ourselves. We help him stay. And so this art that is not, meanwhile, is more fascinating and creates another anonymous art, the tragic one. Whose name will we find? Sometimes things with their absence are more powerful.

FROM THE BOOK “THE UNDERGROUND PANTHEON

OR CONVICTED LITERATURE ”:

The poet, essayist and philosopher Arshi Pipa would be the one who would realize the dream of all Albanian political prisoners in the dictatorship: escape. To flee and show the world the terrible prisons, the suffering of a people without freedom. Writers went abroad, but they did not open their mouths. Shame! Shame 1000 times! Immediately after prison, Arshi Pipa would escape, arriving in Italy with the poems secretly written on thin cigarette papers. It was about the size of a box of matches and he would publish them in Rome in the grim gray summary: The Prison Book, a real hata, where the Canal Sonnets of that terrible swamp would be, in my opinion, “Hell” of Albanian poetry. So, Professor Arshi Pipa had gone to the USA, where he gave lectures at well-known universities, without diverting attention from the literature of the native land, and would even translate from there, as he would bring in Albanian in both dialects great classical poets from the world. The professor would write in English a study “Montale and Dante”, with the permission of Montale himself, which would be in a way, the forerunner of the “Nobel” prize, which would be awarded to the Genoese poet. The corpus of Arshi Pipë’s work is continuing to be published after his death in the homeland in the care of his family, including the manuscripts that his sister Bukuria and his late brother-in-law, the other prison writer, Uran Kalakulla, preserved through dangers.

BYOGRAPHY

FOR ARSHI PIPA:

He was born on July 28, 1920 in Shkodra. He studied at the Severian College in his native Shkodra and then studied philosophy at the University of Florence, where in 1942 he received the title “dottore” in philosophy, with a work on the concept of morality in the philosophy of Henri Bergson. After the fascist occupation of Albania, he returned from Italy together with his brother, Myzafer Pipë. He worked as a teacher in Tirana and Shkodra and editor of the literary magazine “Kritika”. After the Second World War, after the execution of his brother Myzafer, by the victors, Arshi Pipa, in April 1946 he was arrested on charges of activities against the state and sentenced to 10 years in prison. He served his sentence in labor camps in Durrës, in the swamp of death in Vloçisht, in the castle of Gjirokastra and in the hell of Burrel. Upon his release, he fled to Yugoslavia and in 1958 to the United States. He first worked at Georgetown University, Berkeley and then at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. In ’90 he visited Albania. It is greeted with curiosity, misunderstanding, distance and adoration. The first poems he wrote in the late 1930s are included in a ksomble, which would be followed by others. Particularly valuable, the height of Albanian thought are his works in literary criticism, the history of Albanian culture and the politics of language in Albania during the dictatorial rule of Enver Hoxha. He spent the last years of his life in Washington DC, where he closed his eyes on July 20, 1997 in Washington DC.

Also today, on the day of his birth, on the 100th anniversary, we remember that the work of Arshi Pipë is alive and strong, an unquenchable light of a lantern in darkness…/Memorie.al

![“Count Durazzo and Mozart discussed this piece, as a few years prior he had attempted to stage it in the Theaters of Vienna; he even [discussed it] with Rousseau…” / The unknown history of the famous Durazzo family.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/collagemozart_Durazzo-2-350x250.jpg)