By Alqi Koçiko

Memorie.al / After 1945, he was not given a state job or a pension. They took away the Front trisca, the food trisca, but he somehow managed to survive, dealing privately with translations. He died in 1953, in the hospital, when he was hospitalized for treatment of hypertension. If every step of his interesting, but also turbulent life, can be left in the dark, what is worth highlighting today, as a valuable value of scientific economic thought, is the “promemorial”, which on December 22, 1945, sends it “reserved, only for ministers”.

This memoir, a document that was first commented in a dignified way by the authors Fatos Arapi and Trim Gjata, in 1992, is a scientific essay that reveals very well what kind of communist he was and how he saw the future of his homeland. own. We are talking about Kostandin Boshnjaku.

Kostë Boshnjaku was born in 1888, in Lunxëri, Gjirokastra. He completed his studies at the Commercial Institute of Piraeus in Greece. For several years he worked in international banks in Odesa and St. Petersburg, Russia. When Prince Vid’s government was formed in 1914, he was appointed director of the Treasury and the State Debt.

During the “October Socialist Revolution”, he was in Russia and is probably the only Albanian intellectual who has closely experienced the shocking events of Soviet Russia.

He returned to his homeland and became an active witness of the turbulent and hopeful era of the early 1920s, but after the failure of the Nolist government in 1924, he was forced to emigrate (to Austria, Switzerland, Germany, France, Bulgaria, Romania).

During this time, he had friendships with democratic and republican intellectuals, such as; Noli, Ymer Dishnica, Nikola Ivanaj, Halim Xhelo Tërbaçi, Sejfulla Malëshova, Asdreni, Faik Konica, etc.

The latter in 1922 suggested to Noli in a letter that the Bosnjaku was the most favorable personality to be appointed ambassador to Greece. Ahmet Zogu in 1927, sentenced him to death in absentia, as accused of participating in the organization of the assassination against him, in the Austrian capital. When the Vienna police arrested him in 1929, world personalities intervened for his release, such as Einstein, Henri Barbys, etc.

Let’s pause here, because the original document of June 5, 1929, through which the Albanian consul in Vienna, Çatin Saraçi, informs his Foreign Minister, Reuf Fico, about the Bosnian’s arrest, speaks volumes.

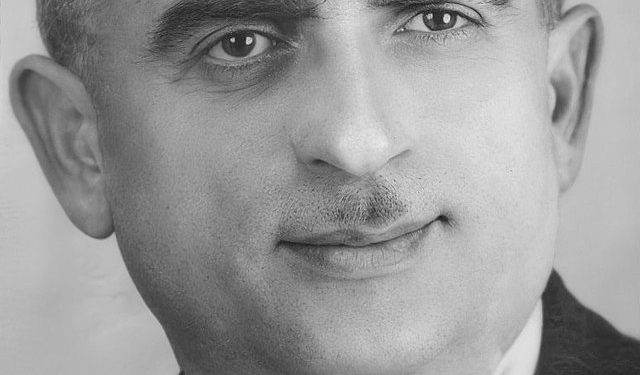

Here are two extracts: “…Bosnjaku’s correspondence was confiscated. They found many letters from Fan Nol, from Berlin, from Lazër Fundo from Moscow, from Columbus from Istanbul… “, or; “This one, with his stupidity, has knowledge of the summary of the res act. No. 170-II, which was sent to this office… maybe among our employees in Qandra, even the word “secret office” is not understood… you know that it is so secret, and never mentions names, in his letters”. And in fact, Minister Fico himself was a close friend of the Bosnjaku, as the photo proves.

It was the era of radical ideas, whether left or right. Which even more harshly than they were propagated, were put into practice with communism and fascism. But it is interesting that the Bosnjaku, during the entire period 1924-’39, lived outside the homeland as a political emigrant, he was part of that class of idealistic intellectuals, who associated communism with well-being and not with Stalinist brutality.

Here is an example: Sometime before 1922, when they asked him in Holland about the ideals of the October Revolution, he answered them that: “Communism is an illusion for human society.”

Kostë Boshnjaku had a wide culture in the field of economics, especially banking. He possessed a scientific competence. He was polyglot: He knew old and new Greek, Turkish, French, Russian, German, English, which he spoke fluently, because he had lived in these countries.

There was a sharp pen from the serious publicist. He was dignified, discreet and taciturn, he was listened to and imposed on others out of respect. His political opinion was based on the first directives of the Comintern, which were then misinterpreted (also) by the Albanian communist regime, but meanwhile every sign of him in the press of the time, the wind of progress blows.

On the other hand, in order to more accurately understand the political, economic and scientific thought of Kostandin Boshjnjaku, we must refer to the historical conditions, all of his activity.

Boshnjaku is included in the cream of intellectuals for the entire mosaic of communists who came from France, Italy, Germany, or Austria, to Albania, who put the Albanian issue in the foreground.

We are talking about that generation of “proto-communists” who were then disappointed, gave up, suffocated in their shell or even physically eliminated, after seeing what communism was translated into the Albanian terrain, as they are; Sejfulla Malëshova, Tajar Zavalani, Koço Tashko, Dhimitër Fallo, Llazar Fundo, Niko Xoxi, etc.

In 1924, he wrote with great respect and appreciation for American President Wilson, for what he did at the Peace Conference in 1920 for Albania; but also for Lenin, on the position he took in the denunciation of the “Treaty of London” in 1915, on the Albanian issue. And Boshnjaku emphasizes that: “We don’t care how many works Lenin wrote, but only what he did for Albania”.

As for his private life, on the few occasions when he was mentioned after 1990, the Bosnjaku was anathema as an adventurer (because he didn’t get married?!). In fact, the marriage certificate bears the number 125, dated July 21, 1940, of the Civil Status office in the municipality of Preza.

Since 1925, he has lived with his only wife, the Austrian Margarete Sehmid. It was in her apartment in Vienna that she was arrested in 1929.

According to his relatives, Kostandin Boshnjaku did not want children, due to lack of economic base, but also due to the fact that he moved around the world, working for Albania. An article of his, in the newspaper “Shqipëria e re”, in March 1934, (page 4), is quite significant, where he criticizes the Albanian parliament, which had issued the law; “For the prohibition of marriages with foreign girls”.

In this same year, from Varna in Bulgaria, he sends an open letter to all the Albanian colonies under the pseudonym, I.G. Connie. In this material of two pages, not only the level, the high social opinion of the author, but above all the contemporary and not at all Bolshevik assessment of the solution of the Albanian issue comes to the surface.

In the intellectual circles of the time, Kostandini is highly valued, and this is shown through the correspondence as well as the dedications expressed in the books donated by them, which are facsimiles in the family archive: from Konica, Hasan Prishtina, Sejfulla Malëshova, to Nako Spiru or, Koço Tashko.

There is even a letter, where Monsignor Luigj Bumçi, expresses thanks on behalf of Princess Sanija (Bird’s sister, his persecutor and death sentence), for the useful cure of folk medicine, which he advised for her recovery.

Kostandin Boshnjaku returned to Albania in 1939. He took an active part in the Anti-Fascist War, being elected one of the 16 members of the leadership of the General Anti-Fascist Council and deputy of the People’s Assembly, in the first post-war elections, on December 2, 1945. We can start this phase of his life with one of the few letters that Enver Hoxha sent him, the one of April 17, 1944, where he informs the 55-year-old about the decision of the Council on the call of the Anti-Fascist Congress:

“Dear Boshnjaku, …I understand very well the reason that compels you to stay there, why I met you in the forests of Martanes, covered with snow; you remained steadfast despite the physical sufferings….!

Do not be afraid about the issue of illness and health, because now summer is ahead and we are in better conditions”. The irony of the future dictator’s interest in the Boshnjaku’s health takes on very poignant tones, given the sequel.

After the war, he was appointed general director of the Albanian State Bank, but immediately after the commemoration, he was removed from his post and at the beginning of 1947, he was arrested under the charge of being part of the opposition leader in the “Group of Deputies”, being called “agent of the Anglo-Americans”. He was sentenced to be shot, then the sentence was changed to 101 years in prison.

He benefited from amnesty in 1949, while another version says that he was released with the direct intervention of the Soviet ambassador, Chuvahin. If this were completely true, there would be no explanation for the fact that the Boshnjaku remained under surveillance, persecuted morally and economically, until the end of his life, even in those years when the Soviet influence in Albania was absolute.

Especially after 1944, the merit of the Boshnjaku lies in the opposition to the agreement made between Albania and Yugoslavia, for the equalization of the dinar with the lek. Such a fact was experienced by his friend from prison, Nexhmedin Ballka, who says: “When they made him general director of the State Bank, Kostandin came to my house and said: I came because Yugoslavia, the Bank requested Albanian, to depend on her bank.

This means that all percentages of the profit will be taken by Yugoslavia and we will lose millions of dollars. We will do one thing: Notify Nako Spiru. When I told this to Nako – says Ballka -, he advised me to keep quiet, ‘because you and I suffer too'”. In fact, this agreement was not realized in practice, but it is known that Nako Spiru and Boshnjaku suffered it later.

Kostandin Boshnjaku has never called Enver Hoxha by name: He always addressed him; “Uncle Halil’s son”, because he was 20 years older than him, and with a culture that did not have any communication vessel, on the level of Hoxha. He did participate in the war, but he could not agree with the Albanian communist leadership.

The Boshnjaku drew the attention of Enver Hoxha: “Look at how things are being done in the neighboring countries, make an amnesty, be careful that, in the war, we do not do it for revenge. Don’t commit assassinations…”! The advice, of course, fell on deaf ears.

The life of Kostandin Boshnjaku reflects tragedy even after his release from prison. Together with the wonderful friend of his life, they lived only with the translations, which he did and his wife typed them with a typewriter.

Here is a passage of disappointment, which Nexhmedin Ballka tells again: “Kostandin Boshnjaku had a brother in Durrës, where he stayed for a while and in very difficult conditions. One day I met him and he took me to the sea port. There I see Demir Godell (former communist of the early times) who made a living as a translator…”!

Enver Hoxha had found the end of the more educated, more cultured, more patriotic people, who embraced the communism of the early years, only to see Albania in a truly democratic well-being.

It is enough to read the Bosnjaku’s introduction to understand what kind of Albania he wanted. Because the essence of Kostandin Boshnjaku’s personality is the respect of his own convictions under the motto: “The truth may not make us poor, but it will make us free”. Memorie.al