From Prof. Dr. Përparim Kabo

Second part

Memorie.al / The acceptance of the unification of the two Germanys by Gorbachev, on the 40th anniversary of the creation of the German Democratic Republic, surpasses the geopolitical assessment of the post-World War II era and the acceptance of a simple unification within the framework of the expanding global market, which, as Mikhail Gorbachev stated, “did not conflict with the assessment that the new policy (Perestroika) gave to this fundamental issue.” But there are also two points of emphasis that play a key role in the judgment of the event: the unification of two countries with opposing systems, capitalism in the Federal Republic of Germany and communism in the German Democratic Republic, as well as the latter’s transition to the side of NATO.

Continued from the previous issue

The Circumstances That Led to the Hungarian ’56

In summary, the main causes are accepted as: The economic collapse and low standard of living, which provoked discontent among the working class. The peasantry was unhappy with land policies. The Communist Party was unable to unite its reformist and Stalinist factions (it is understandable that these exclude each other). Journalists and writers were dissatisfied with the workers’ conditions and the general situation and could not stomach the Soviet military presence, although until that time, it had only been in barracks. These intellectuals escalated their position and action and, in the process, took control of the workers’ unions.

Khrushchev’s speech about the Soviet government under Stalin’s leadership had caused much debate among the leading elite of the Hungarian Communist Party. But while the Communist Party was blinded by the leadership debates, the people took action. Therefore, from this perspective, the circumstances, factors, interests, and human relationships must be illuminated. The international relations and the created relations between the West and the East must be re-evaluated, the clash of which in 1956 precipitated in the center of Europe, but more accurately, it can also be said in the heart of the continent, where any change or upheaval affects global balances. The Potsdam Agreement recognized Hungary as a defeated country and under Soviet influence, and furthermore, because Hungary became a member of the Warsaw Pact.

The free elections of 1945 resulted in a coalition government. Under the imposition of Soviet Marshal Kliment Voroshilov, the government was forced to give some important posts to the Communist Party (Magyar Kommunista Párt or MKP), which had won only 17% of the votes in the post-war pluralistic elections. The Minister of Internal Affairs who came from this party was Lazlo Rajk. He established the protective authority of the state through a secret police linked to and as an extension of the Soviet NKVD, which pressured and eliminated the religious, nationalist, and democratic opposition. (Rajk was a sort of Koçi Xoxe and, like him, had the same end: he was eliminated by his own for treason).

After this short period of multi-partisanship, the Communist Party, now called the Hungarian Workers’ Party (Magyar Dolgozók Pártja or MDP), having absorbed the other political parties, encouraged their candidates not to put up any opposition in 1949, when Hungary was being transformed into a communist state, the “Hungarian People’s Republic” (Magyar Népköztársaság), under the dictate of Mátyás Rákosi. The possessive authority of the state began purges from 1948-1953. Party dissidents were denounced as “Titoists” and “agents of the West” and were sentenced through open show trials.

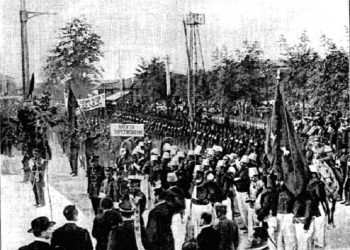

Thousands of Hungarians were arrested for their political opposition. They were tortured, imprisoned in concentration camps, or executed, including MDP veterans such as Laszlo Rajk, and many others. (How similar this is to post-war history. The essence is the same: the communist system was imposed with terror and violence, with fear and purges against the urban elite of society, but also against those who were considered opponents within the system). The hatred against the rule of the MDP elite, against the extreme nationalists, as well as against the Soviet occupier, was reflected in the students’ petition with 16 demands made by the demonstrating students who rose up on October 23, 1956. These demands included the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Hungary, the removal of the MDP leadership, and the release of political prisoners.

As an ally of Nazism, Hungary had accepted the agreement for reparations and compensation amounting to about $300 million within 6 years, which would be paid to the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia after the end of World War II, as well as financially supporting the Soviet garrisons in Hungary. Due to the very high post-war inflation, the Hungarian National Bank estimated that the cost of reparations amounted to $500-584 million per year, a figure that fluctuated from 19-22% of the national income at that time.

Moreover, Hungary, like all the countries of the Eastern Bloc, dependent satellites of the CMEA (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance), was deprived of trade with the West or supplies from the Marshall Plan, which could have revitalized the Hungarian economy. Thus, partly due to the loss of a part of its industrial assets as payment for reparations to the Soviet Union, Hungary’s economy in the post-war period experienced a significant decline. Overall production went down to 1/3 of its pre-war level.

The Hungarian currency, the pengő, experienced a substantial depression, and in the post-war period, Hungary suffered from such a high hyperinflation, the highest documented in its history. In the early 1950s, the Soviet-style of economic planning was implemented by the Rákosi government, agriculture was collectivized, and the profit from this sector was used by the state for the expansion of heavy industry. The manipulation of wage control and the differentiated prices for producers and consumers was, so to speak, the “fuel” of discontent, as well as the increase in the foreign debt deficit.

On the political front, what is called “post-Stalinist liberalism” was a force for change and an expression of a liberalization of life even within the system. On March 5, 1953, Joseph Stalin died, leaving a power vacuum in the upper ranks of the Soviet Union, which for a short time led to a period of destabilization during which anti-Stalinist sentiments were tolerated. A reformist wing had begun to develop in many communist parties. In Hungary, Rákosi was forced to allow the reformist Imre Nagy to become prime minister in 1953, although he remained the General Secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party at the time.

Moreover, Rákosi’s authority had been mentioned by Khrushchev in his February 1956 speech, where he denounced the policies of Stalin and his defenders in Eastern Europe, emphasizing that the show trials had been unjust. The consequence of this exposé was the decision Rákosi made on July 18, 1956, to resign from the post of Party General Secretary, and he was replaced by Ernő Gerő.

Within the socialist camp, after the death of the Soviet dictator, anti-Soviet movements were noticed. Thus, on June 17, 1953, East Berlin workers rose up, demanding the resignation of the East German communist government. This movement was immediately suppressed by force, with the help of Soviet military forces. There were deaths, the number of which ranged from 125-270. In June 1956, there was also a workers’ revolt in Poland, which was suppressed with a toll of 74 dead. So, liberal post-Stalinism, which was moving toward autonomy and even secession from Moscow and its chains, culminated in Hungary.

But its secession would mean not simply the departure of a satellite country, but the disruption of European and broader balances between what were called two opposing blocs. The Hungarians wisely chose to identify the departure from the socialist camp and the Warsaw Pact not with a move to NATO, but with the neutrality of Hungary. The Soviet Union could not accept this challenge, first because Hungary would move toward capitalism, even as a neutral state in international politics, but also because such a precedent could spark a chain reaction. The Soviets also judged the situation in relation to international events. On May 9, 1955, 10 years after the fall of the Reichstag, West Germany joined NATO.

The Norwegian Foreign Minister at the time, Mr. Halvard Lange, evaluated this event as: “A decisive turning point in the history of our continent.” On May 14, 1955, the Warsaw Pact was created by the Soviet Union and its satellite countries. Not without irony, in relation to the not-so-distant and close realities on which the Soviet Union acted in the name of this pact, which supposedly was based on the principles of friendship, cooperation, and mutual assistance, it was written: “Respect for the independence of states’ sovereignty and also non-interference in their internal affairs.”

On May 15, 1955, the treaty with the Austrian state was signed, ending the occupation of Austria by the allies and establishing it as a neutral state. This treaty was declared as quite significant, as it changed the calculations of Cold War plans, because a neutral dividing cordon was established for NATO from Vienna to Geneva, and the strategic importance of Hungary’s position in the Warsaw Pact was raised.

In July 1956, Gamal Abdel Nasser, the President of Egypt, nationalized the Suez Canal and the oil transport lines by ship to Western Europe and the USA. The British Prime Minister at the time, Anthony Eden, initially called for the non-use of force, warning Nasser of a possible attack. In the period from July to October 1956, the initiative encouraged by the USA to lower the tension proved unsuccessful. A secret alliance between Israel, France, and Britain was defined to invade Egypt and Britain and France would intervene to secure the canal.

The attack was carried out on October 29, 1956, leaving the USA and other Western allies with the opportunity to justify a limited criticism of the Soviet military intervention in Hungary, while not stopping the actions of their two main European allies. It seemed as if military activity in the zones of influence was virtually allowed (not hindered), with the difference that what happened in the attack on Suez had the name “oil,” while what happened in the heart of Europe had the name “Hungary.”

But the situation was very complicated. The Americans and the West were concerned about Soviet penetration into the Middle East and the supply of Russian weapons to its allies in the region. Egypt was not easily given up by the Russians, so much so that Khrushchev at that time declared to the Yugoslav ambassador that if Egypt is attacked, I will not hesitate to send my son to war. Israel was used as a means of war and a pretext for attack by the British and French, so on October 28, 1956, it occupied the Sinai, and two days later, France and England demanded its withdrawal and that of Egypt from control over the canal. This was the scenario prepared by the two European powers, which, as events unfolded, did not work. A week later, the general elections were held in the USA.

“Eisenhower was deeply offended by a maneuver that was, it seems, linked to the assumption that he could not oppose his Jewish voters in the last week of the election campaign” (Henry Kissinger, ‘Diplomacy’, Albanian edition, page 541). In a session after midnight on November 3-4, 1956, the United Nations General Assembly passed a very harsh resolution and began to discuss a UN peacekeeping force for the Suez Canal, simply as a maneuver to withdraw the French and British forces, since the presence of UN forces would also depend on the desire of the sovereign state itself, so it was understood that Nasser himself would demand their departure.

America felt humiliated by its closest allies. But on the same day, November 4, 1956, 150,000 Soviet forces supported by thousands of tanks-most of them, ironically, or sneakily used as such, were German tanks that had been used by the Nazis in the war against the Soviet Union and had been captured by the Red Army. “In 1956, two simultaneous events changed the pattern of international relations.

The Suez Crisis marked the end of naivety for the Western Alliance; from that time on, Western allies would no longer trust their claims of a perfect symmetry of interests. At the same time, the bloody suppression of the Hungarian uprising showed that the Soviet Union could preserve its spheres of interest even with force, if need be, and that the calls for liberation were empty words. There was no doubt that the Cold War would be long and bitter, with opposing armies facing each other along the dividing line of Europe, and for how long no one knew.” (Henry Kissinger, ‘Diplomacy’, Albanian edition, pages 550-551).

Also on November 4, the Security Council approved a resolution critical of the Soviet military action. The General Assembly, with 50 votes in favor, 8 against, and 15 abstentions, demanded a halt to the Soviet intervention. But the newly constituted Kádár government refused to accept the UN observations. Thus, the efforts of the “Radio Free Europe,” which urged the Hungarians to keep the resistance going with the aim of NATO and UN forces intervening, proved to be uncalculated. The NATO Secretary General, Paul-Henri Spaak, called the Hungarian revolt “the collective suicide of an entire people.”

Apology…!

In 1988, the Hungarian Ambassador to the UN, Géza Jeszenszky, criticized the West for its inaction in 1956, citing the UN’s influence at the time and giving the example of the UN intervention in Korea in 1950-1953. Giorgio Napolitano, who at that time had been the secretary of the Italian Communist Party (PCI), wrote in his 2005 memoirs (political autobiography) that he regretted the Soviet justifications for their actions against Hungary.

In December 1991, when Hungary concluded a bilateral agreement with the Soviet Union, which was being torn apart under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev and Russia, was represented by Boris Yeltsin, the introduction to the agreement officially requested an apology for the bloody 1956. This apology was repeated by Yeltsin in 1992, in a speech in Parliament. February 13, 2006, the US “State Department” commemorated the 50th anniversary of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.

Is there room for an apology and a “penance mass” in Albania as well?

Because even the most sincere efforts of that time, which in our country also sought to eliminate Stalinism and open the way for a more democratic, more liberal, less authoritarian spirit within the system itself, were struck by Stalinist radicalism. It did not stop even at the execution of a pregnant woman (Liri Gega) and other early anti-fascist fighters. But for these purges, crimes, and persecutions against those liberal citizens and opponents of the pro-Soviet government, also inspired by the Hungarian storm of 1956, which resulted in imprisonment and internment, still no one dares to ask for a public apology.

We called the Hungarian Revolution a “counter-revolution” at that time, and the left-wing forces in Albania, starting with the main one, the Communist Party, and all its sister parties, have not asked for an apology for this stigmatization, which is as ignorant in its theoretical evaluation as it is anti-human on a human level. But this event has not yet become even a point of reflection to understand that the failure to pass that phase, which in the East was called modern revisionism, led to all those who remained in politics and were converted to the new parties of pluralism on the eve of 1990 and in the years that followed, bringing with them into their consciousness, in their psychology and morals, in their political philosophy and way of behaving, a harsh, arbitrary, and radical style.

While in our anthropology, a total lack of civil courage is evident to take to the streets and fight in the name of truth and its morality. This is why no one among us asks for a sincere apology, as we have not yet cultivated a civic consciousness that knows how to ask for and take the responsibility that arises from an apology, as a noble act of civilized people. This kind of consciousness has been created through the traces of history, the culmination of which for the Hungarians, but also for others, is the popular clash of 1956, which these days comes with the importance of an epochal event. A reason for reflection and self-purification on the path that has begun for us Albanians as well. / Memorie.al